March 11–May 9, 2015

Opening: Wednesday, March 11, 7pm

The artist will be present.

Hilger NEXT

Absberggasse 27/2.3

1100 Vienna

Austria

Hours: Wednesday–Saturday, noon–6pm

T +43 1 512 53 15 200

michael.kaufmann@hilger.at

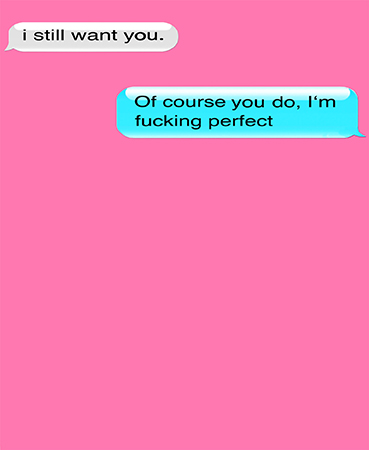

In his fourth solo show with Galerie Ernst Hilger, Swiss photographer Daniele Buetti reflects on new forms of communication in the 21st century. Exhibited are large format prints, focusing on text messages and how these have changed not only how we communicate, but also (the English) language itself.

The medium—the omnipresent text message—forces the writer to condense her thoughts to a minimum of characters. The result is not only a rampant use of acronyms, emoticons and abbreviations, but also the leaving out of whole words and word chains. While this is by some mourned as the “death” of the English (or any) language, it is seen by others as a natural evolution. Buetti points out that the forming of a new vocabulary is also a creative act. Some users focus on the alteration and adaption of words, others establish a unique system consisting solely of emoticons and pictograms. The use—and understanding of—acronyms, abbreviations, and pictograms also serves to establish identity. It declares the writer as part of a certain group, in which all “legitimate” members understand the code and those that do not belong, are easily unmasked.

Inherent to a text is also the spatial separation between writer and receiver. This physical buffer gives many the confidence to speak more frankly, in contrast to a face-to-face confrontation, which cannot be dismissed or “silenced” by the push of a button. But although it may seem easier to solve emotional conflicts this way, the shortness of the message, and the code used, can also lead to misinterpretations. And not to forget autocorrects or spelling errors, that in the flurry of typing, are overlooked and sent, at times with dire consequences.

The conversation snippets that Buetti appropriates are not made up, instead the artist has scoured the internet to find seemingly authentic conversations gone awry. He categorizes these into five groups: sending a message to the wrong person; seemingly uncontrollable autocorrects; parents adopting their children’s language—more, or less, successfully; the growing gap between generations’ conventions and expressions; the contrast of private/public and voyeurism/self-reflection.