The Futuristic

In January of this year, the world was watching China and perhaps taking some pleasure in its misfortune. For people outside of China, it was probably indeed thrilling to be (virtually) part of such an event. Here is how I both imagined and experienced the thrill unfolding in early 2020: even thinking about it secretly made your palms sweat. It was a real event in real time (more exhilarating than any Hollywood movie, video game, or any past catastrophe) but happening remotely (you knew you were safe or at least not in immediate danger); it was electrifying but not deadly (yet). Admit it! Just like Žižek did in late January:

I must admit that during these last days I caught myself dreaming on visiting Wuhan. Do half-abandoned streets in a megalopolis—the usually bustling urban centers looking like ghost towns, stores with open doors and no customers, just a lone walker or car here and there, individuals with white masks—not provide the image of non-consumerist world at ease with itself?1

What Žižek describes is pretty much the best possible setting for an apocalyptic sci-fi movie.

It is particularly dangerous when something from the cultural imagination is later read as a reliable prophecy, since it renders the abstraction and alienation of human suffering as a set of perpetuating clichés. For example, the only similarity between the current pandemic and the “predictions” pulled from Dean Koontz’s 1981 novel The Eyes of Darkness, noted on social media this February, is a reference to a killer virus called “Wuhan-400” that emerged from the Chinese city of Wuhan. As the reality of the pandemic unfolds globally, “China” continues to operate as a spectacle in both intellectual gossip and pop-cultural speculation. But we need more than just an arbitrary imagination of the suffering. There is rage, confusion, fear, and despair: concrete and real.

In 2018, when I commissioned artists to create new work for the exhibition “One Hand Clapping” at the Guggenheim Museum, I prompted them to speculate on the future of China with keywords such as “technology, system, myth, ghost, disaster, chaos, absurdity, uncanny, medium, togetherness, existence, humanity, and utopia.”2 Throughout the exhibition, we tried to expand discussions on the understanding of “China,” from a geospatial location to a framework of temporality. Such temporal fantasies of China have evolved significantly in recent years: from the cliché of a civilization with “five thousand years of history,” to a nation on the rise, ultimately “taking over the world.” We explored the West’s prevailing fear of the country’s economic and technological ascent, the myth of “happiness for all” promoted by the Chinese government, and the political imagination of a nation entirely managed by a totalitarian, AI technocracy. As futuristic or apocalyptic as all these visions may be, we did not think of another possible scenario, perhaps the most futuristic and apocalyptic of all: an unknown and highly contagious virus, originating in China from hard-to-identify sources, soon to spread across the globe.

Shanghai

My partner and I arrived in Shanghai on January 21 to celebrate the Spring Festival with my family. It was his first time in China, and we planned to spend a week in the city. The Spring Festival is my favorite of all holidays. Despite the highly globalized urban environment of Shanghai, many fond traditions still trickle down. Leading up to New Year, my family’s house is always bustling and filled with aromas. My father likes to decorate the apartment with seasonal flowers. About two weeks before, he had carefully placed narcissus bulbs with pebbles in shallow water containers and eagerly anticipated their blossoming around New Year’s Day. Mom had begun preparing ingredients for the New Year’s dishes weeks ago. My favorite of her dishes is her thinly sliced homemade bacon, stir-fried with garlic scapes. Father usually prepares rolls and sheets of red paper so we can write couplets together and paste them onto the apartment doors; the Spring Festival couplets are composed of a pair of poetry lines hung vertically on both sides of the door, with a four-character horizontal scroll attached above the doorframe. The poetry, based in folk culture, often expresses people’s delight in the festival and their wishes for a prosperous life in the coming year.

According to legend, in the world of ghosts and spirits there is a rooster that perches in a big peach tree. He crows at dawn to call back all the traveling ghosts. People in ancient times believed that peach trees could scare and subdue evil things, so they hung peach-tree boards in front of their doors for protection. Over the years, the boards were replaced by paper, and people began to focus more on wishes for the future. Amulets became mascots. The tradition became part of the New Year celebration, and also formed its own vernacular literary genre. I love all these little heart-warming details about the holiday time. But this year, the red paper couplets were not very effective.

Just like my parents, people in the rest of the country were also busy preparing for the Chinese New Year. There is nothing unique about my family’s traditions. These are the simplest but most anticipated activities of the year. They become even more precious for people like me, students and migrant workers who live very far away from their families and traditions. So we use the holiday period to travel across the country and the world to join our families. In 2019, the total number of domestic trips made across China for the Lunar New Year Spring Festival was nearly three billion. Nothing can stop us. Not even the virus.

Meanwhile, on January 18, just a few days before the complete shutdown of Wuhan, the Bai Bu Ting community organized their annual “Ten-Thousand Family Banquet,” an event that asks every family in the community to contribute a dish to the Lunar New Year celebration. Held annually for the last twenty years, the banquet is less a collective meal than a local government showcase of the community’s “prosperity.” Over forty thousand families participated in the carnival, amidst the still “unknown” outbreak. This otherwise merry time set the perfect conditions for the spread of the epidemic.

January 22 was an uneventful day for us. We set out on foot to have lunch with a friend and walked around in the French Concession district. It was business as usual. Although I had many things planned for my partner, jet lag hit hard and we decided to go home that afternoon. There is always tomorrow, we thought. Later that day, we started to hear rumors that major tourist attractions were shutting down, including the Shanghai Museum that we had contemplated visiting that afternoon. My plan for a “perfect first impression of China” tour was falling apart.

Wuhan: Not in a Dream

A few hours later, the central government announced the lockdown of Wuhan. It was just one day before New Year’s Eve. During the eight-hour window between the announcement and its implementation, millions of people fled Wuhan in a panic.

No one quite understood what a lockdown entailed until things started to get really bad. The social media posts were very sensational. It was literally impossible to separate real news from fake news. Many so-called rumors later became truths, and many official updates turned out to be lies and cover-ups. I started to give up on discerning what was real and what was fiction.

My heart broke when I read that a senior citizen in Wuhan had to walk for hours to get to the hospital because public transportation in the city had stopped, only to get turned away because there were not enough beds and testing kits. I imagined the feeling of not be able to breathe despite the imperative to continue walking for miles. Then there was a young woman following a white van and crying in despair. It appeared to be a hearse carrying her mother’s dead body directly from the hospital ICU to the crematorium. She did not get to say goodbye. Just a few days earlier they were preparing for the Spring Festival and buying groceries together. I imagined being that woman, because we were of similar age. There was also an ordinary middle-class family of five that was completely shattered in the span of a couple of weeks. The son was studying aboard in a foreign country alone. After his retired grandparents who had been doctors contracted the virus, his father, a local radio show producer, began taking care of them but soon fell ill too. The three of them died consecutively; it’s possible that his mom tested positive too, though I don’t know for sure. I imagined being that son: How could I face a broken family when I returned home from thousands of miles away? I had no time to reflect on whether my empathy was cheap, but it was certainly real. I could be any of them.

Over time, people compiled and edited an exact timeline of the missteps that the government had taken, leading to the disaster in Wuhan.3 Obviously the local government had known about this mysterious new virus for weeks (if not months) prior to the lockdown, but they were occupied by the annual plenary session of the local People’s Congress and the local committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conferences, commonly referred as Lianghui (Two Meetings). During these five-day meetings, the two organizations make local-level political decisions. During these five days, everything is supposed to be perfect. How could there be a potentially deadly virus spreading around?

The internet exploded when, on February 7, a thirty-three-year-old doctor named Li Wenliang died in a local hospital in Wuhan after contracting the virus. Netizens called him a whistleblower and a hero. Several weeks prior, on the second-to-last-day of 2019, he had shared with a WeChat group of his old classmates his concern about a novel virus that seemed similar to the SARS coronavirus. He simply wanted to remind his fellow physicians to protect themselves and their families. He didn’t expect that four days after posting this, he would be called to the police station to have a “conversation” and sign a “discipline paper.”

The “official exhortation” in the “discipline paper” read: “The public security department hopes that you actively cooperate with our work, follow the advice of the police, and stop the illegal behavior. Can you do it?”

Li signed “Can” and pressed his fingerprint. The document continued: “We hope you reflect carefully and calmly. We solemnly warn you: if you are stubborn, do not repent, and continue to carry out illegal activities, you will be punished by the law! Do you understand?”

Li Wenliang, thus admonished, signed “Understand” and pressed his fingerprint again.4

The image of Li’s signed “Can” and “Understand,” along with his fingerprints in red ink, was made public and soon went viral. In addition to Li, seven other physicians were investigated by the Wuhan police for “rumor making.” A report about the local police heroically terminating the treacherous rumor was reported on CCTV’s prime news program and was relayed by numerous local channels. But people started constructing a counter-narrative on WeChat and Weibo by posting “Can’t” and “Don’t Understand” and demanding transparency and real information. For a brief moment in early February (until censorship kicked in), the top two trending hashtags were “#TheGovernmentOwesDr.LiWenliangAnApology” and “#WeWantFreedomOfSpeech.” There were even posts articulating a list of Five Key Demands, mimicking the format used by the Hong Kong protesters.

I have never seen such open and clear demands circulating on the internet in China in my lifetime. So I joined in. I had no time to reflect on whether my rage was insignificant, but like my empathy a week earlier, it was certainly real. I could not stop associating the image of Li Wenliang’s red fingerprints with a short story by Lu Xun called “Medicine.” Written in 1919, it tells the story of a sick boy who is fed a secret medicine to treat his tuberculosis: a mantou (steamed bun) soaked in human blood—more specifically, the blood of a rebel recently beheaded by authorities. Touted as a “guaranteed cure,” the mantou medicine fails to save the boy. He dies from his illness.5 The sight of Li Wenliang’s red fingerprints kept evoking in my mind the image of this blood-soaked mantou.

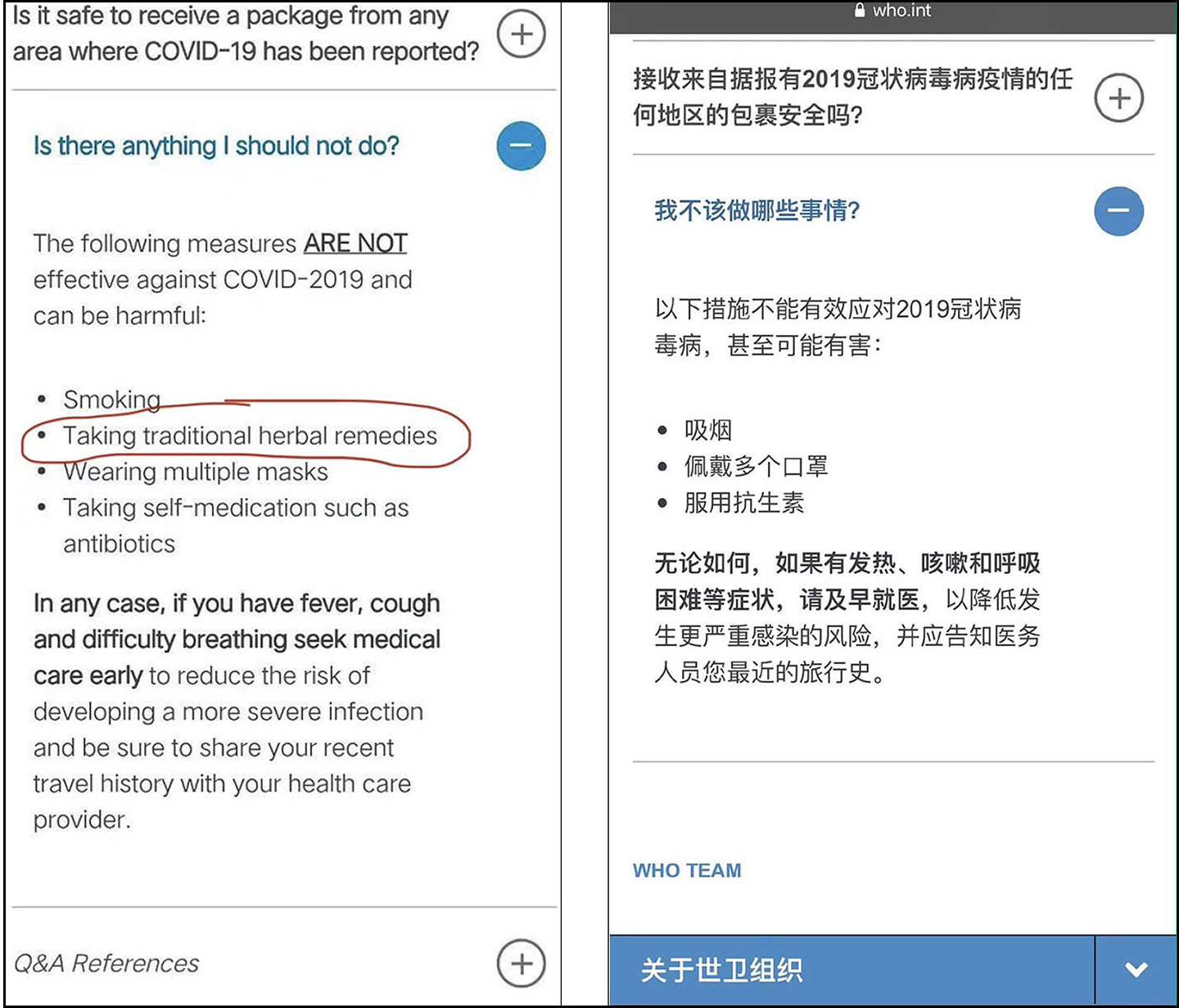

In the World Health Organization’s answer to the Q&A question “Is there anything I should not do?” regarding COVID-19 one of the lines included was “Taking traditional herbal remedies.” However, the line was not included in the Chinese version of WHO’s webpage.

Chinese Medicine: Myth or Method

I return to Lu Xun over and over again. His stories never lose their relevance. “Medicine” has a clear resonance with the present, though I haven’t wrapped my head around whose blood might be saturating the mantou today. For Lu Xun, the “steamed bun dipped in blood” is a reference to traditional folk medicine, but also a metaphor for superstition. The current leadership in China has recently begun promoting traditional Chinese medicine, not only as a complement to modern medicine but more importantly as an effective medical tradition, unique to China, that combines technological and cultural heritage and claims to achieve otherwise impossible results. In the battle against coronavirus, Chinese medicine has been recruited to the cause. For example, the China Health Commission’s “Diagnosis and Treatment Plan for COVID-19 Infection” lists a herbal formula named Lianhua Qingwen, which has ingredients such as honeysuckle, mint, and licorice, and which has become so popular that it’s constantly out of stock.6 However, no empirical scientific research has verified its antiviral properties, so its effectiveness remains “theoretical.”7

While Lu Xun was an avid critic of “old thinking” and a leader in the movement to modernize Chinese literature, he nonetheless had a profound love and appreciation for folk culture and traditions. He was often miscast as vehemently opposed to anything traditional. In fact, what he detested were simplistic generalizations about “Chinese culture.” Scholar Wang Hui pointedly argues that the essence of Lu Xun’s

criticism lies in revealing the historical relations between the common beliefs to which people have grown accustomed and morality—this is an historical relation that has never been separated from the social mode of the dominating and the dominated, of the ruler and the ruled. For Lu Xun, no matter how ingenious culture or tradition is, there has not been in history a culture or tradition that could break away from the relations of domination mentioned above.8

Following this line of thinking, it’s easy to see that the narrative of Chinese medicine is a strategy used to strengthen and legitimize the ruling powers within China—much more so than a strategy to export soft power. Based on thousands of years of practice, the story of Chinese medicine is more rich and complex than the version that the Chinese government is deploying. But it has a much larger mass base than more esoteric forms of ancient knowledge, making it ripe for nationalist exploitation. The revival in China of what some define as “neo-Confucianism” is expected to “contribute to the realization of the Chinese dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”9 For the Chinese Communist Party, it doesn’t matter that the image and understanding of Chinese medicine remains a mythical blur, as long as the contrast between the abstract characteristics of “Chinese culture” and “Western culture” persists. This contrast renders Chinese heritage unique, invaluable, and profound, boosting national confidence. To keep Chinese medicine indecipherable to other systems generates a deliberate “space of imagination,” which in turn reinforces its nationalist value.

As the outbreak grew worse, the World Health Organization addressed the efficacy of herbal remedies in the Q&A section of its English-language website. In response to the question “Is there anything I should not do?” it listed “taking traditional herbal remedies,” alongside “smoking” and “wearing multiple masks.” But in the Chinese version of this page, the line about “herbal remedies” was omitted. (Later, the line also mysteriously disappeared from the English version.)10

Spectacles and Un-forgiveness

Lu Xun certainly warned us. In his eyes, “the heroic sacrifice of the few oftentimes only provides a ‘spectacle’ for the amusement of the pitiless masses.”11 In the case of this crisis, medical workers, senior citizens, the less privileged, and even the citizens of Wuhan are the sacrificed few. Is the rage expressed on social media merely a time-sensitive response to this spectacle? Is the collective rant and rave itself a spectacle?

The media, along with the rest of us, have succeeded in generating many spectacles out of this crisis: the rapid construction of two emergency field hospitals in a week’s time; the overnight transformation of unused exhibitions centers and stadiums into hospitals; the transplanting of guangchang wu (plaza dancing)—an exercise routine made popular by middle-aged and retired women and collectivity performed to music in urban squares, plazas, and parks—to these field hospitals, led by nurses covered in protective gear; the arrival of thousands of volunteer doctors and nurses from numerous local hospitals across the country to the city of Wuhan and Hubei Province; and the motivational reportage about women doctors and nurses continuing to work on the frontline despite, for example, suffering an accidental abortion, or having to give up on breastfeeding their newborns. These spectacles not only feed the desire to know the “truth,” but also fuel the propaganda machine. By replacing truth with spectacle, the machine operates effectively.

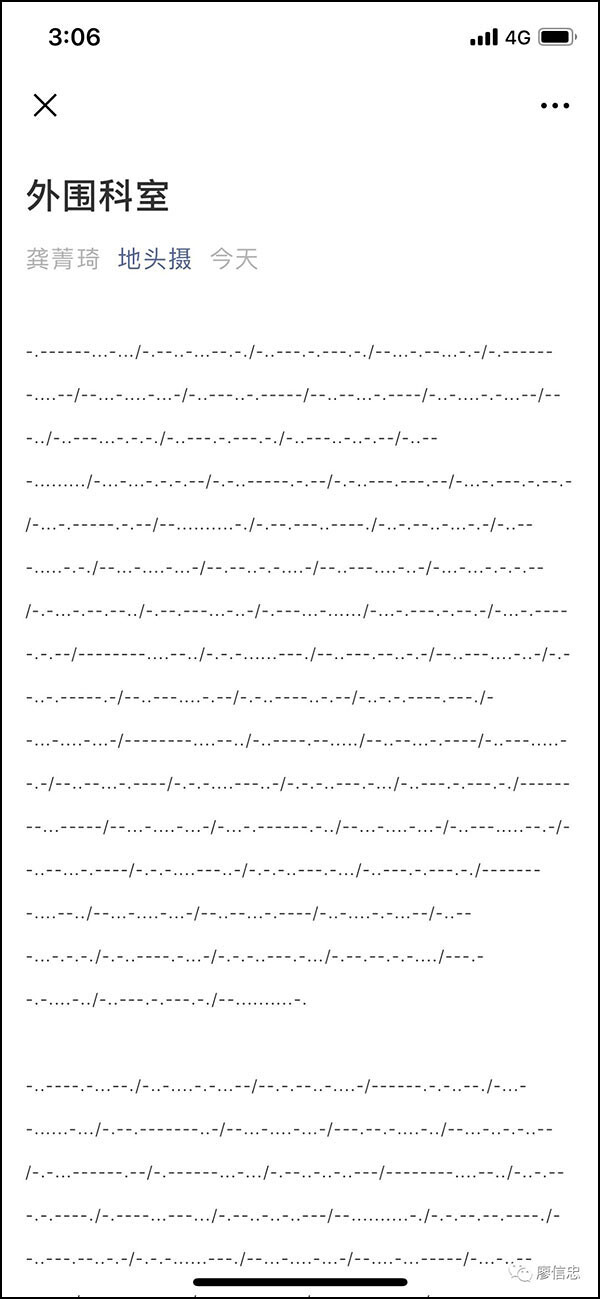

A Chinese social media post was written in morse code in an attempt to counter censorship.

Perhaps here lies the real intention of turning the sacrificed few into heroes: the diversion of attention means that the process of forgetting kicks in faster. In his late years, Lu Xun was extremely harsh and paranoid. He longed for revenge. He believed that maxims like “do not take revenge” or “forgive past traumas” were but the strategies of assassins and their stooges. The government knows this well. Before we have time to mourn each new loss from the virus, there is already another wave of propaganda that is produced and circulated: the so-called “gratitude” genre to help us “forgive past traumas” and be thankful. This genre, exemplified by a music video featuring a young boy signing, perpetuates various narratives that thank the almighty Communist Party for stopping the spread of this evil virus. Of course, there are intellectuals today warning that “we must not forget” what happened to these whistleblower doctors. But how? There have not been any effective channels for expressing demands, not to mention means of self-organized protests, in Mainland China for several decades. Without such infrastructure for solidarity, we all slip into silent complicity.

However, I’m still uncertain whether the act of forgetting is indeed an agenda pushed by the system, or a built-in survival mechanism of humankind. If we make history immune to amnesia and resurrect atrocities of the past for the present, how can we endure the pain and trauma over and over again and continue to exist?

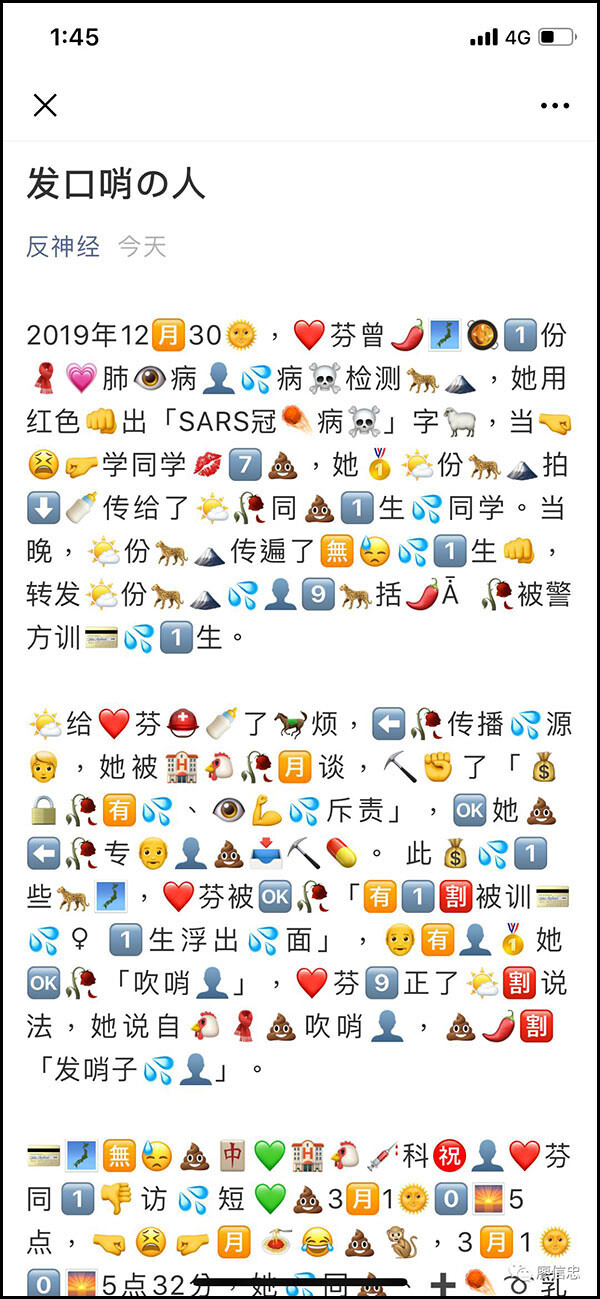

A Chinese social media post was written with emojis in an attempt to counter Government censorship.

#404

The screenshots I saved on my phone after the virus first broke out have become especially precious to me. As the hashtags, demands, and articles that expressed opinions on transparency, freedom, and the government were swiftly deleted, the only way to repost, to continue sharing, or even just to save things for my own reading, was to encrypt the posts in some way. Simply reposting texts as screenshots soon lost its efficacy. When #404 became the norm, it gave birth to all sorts of creative anti-search encryption, such as vertical typesetting, reversed typesetting, and text written in oracles, emojis, Morse code, braille, and even Elvish and Klingon. As people collect and put these posts together, one question remains: Why are all the encrypted versions of these posts still deleted? Who in the community casually reports this “unlawful content”? Are the “internet safety officers” who review this content giggling while they press the “delete” button?

I laughed hard at a video collage that mashed together footage of various newscasters announcing that the whistleblower doctors in Wuhan were being punished in accordance with the law. The newscasters, all sitting in front of an almost identical blue background, read from the exact same script and have the same facial expressions. The video ends with a red palm mischievously slapping each of the newscaster’s faces, accompanied by a goofy sound effect. This wickedly funny video reminds me of a much older and now-classic work by artist Zhang Peili. The single-channel video Water (Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary) features a famous newscaster, who was then the face of state-run television in China, reading a lengthy definition of “water” from a Chinese dictionary in a neutral and monotonous tone. I am not entirely sure what triggered this association. Is it the blue background that appears in both videos? Or is it that both videos ridicule institutionalized norms by replicating them?

The Anti-spectacle

Underneath the tentacles of the “almighty” government there are many “useless” individual stories. Everyday humor—mundane, dark, or absurd—functions not only as a survival mechanism but also an antibody against mainstream propaganda.

In Chinese cities, communities and housing complexes are managed in a unique way. There is a concept called xiaoqu—translated literally as “small neighborhood”—which is similar to a gated community. Depending on the size of a xiaoqu, there can be over a dozen or even a hundred residential units. Each xiaoqu is managed by a neighborhood committee. Its responsibilities are often administrative and practical, such as sanitation and building repairs, but it also has more cultural duties, such as mediating disputes between family members and neighbors. During the quarantine and self-isolation period, these neighborhood committees were assigned the new responsibilities of collecting patient data, coordinating hospitalizations, implementing isolation and quarantine controls, and delivering food and supplies. In order to enter and exit the xiaoqu, each resident would have to report to the committees at the gate, get their temperature taken, and state the reason for their necessary travel.

Such top-down and collective structures have proven to be highly effective in slowing down the spread of the virus, but they require a “sacrifice” of individual privacy and will. At the same time, they have led to the formation of new relationships.

Many announcements within the xiaoqu are made through loudspeakers, a management tool widely used in the early days of communism in China. There is a video that shows one such community in northeast China. The staff member on duty forgot to turn off the microphone after broadcasting the nightly notice, and fell asleep. As a result, the residents of the entire community were immersed in the sound of his snoring. The profound amusement in this slightly surreal scenario does not come from an intimate moment made public, but rather a strange state of collision of between being human and being a cog in a bureaucratic machine. It is an accidental counter-spectacle—something deeply humanist.

This reminds me of the 2009 Lyon Biennale, curated by Hou Hanru. In the introductory text, he argues that in the age of globalization, we now live in a society where any “outside” of the spectacle has become impossible to reach. This is the very condition of contemporary life. It is a social order “guaranteed” by the established system of power. Hanru urges us to (re-)engage the idea of the everyday, the quotidian, proposing that this is the realm where new possibilities and alternatives can emerge. He discusses how art can actively appropriate the everyday to make it relevant again: “The Spectacle of the Everyday is fundamentally changing both the spectacle and the everyday!”12

New York

A couple nights before flying from Shanghai back to New York, we ventured to Pudong’s Central Business District. A spring mist had wrapped itself around the skyscrapers, making them look smaller. Only the red lights on their rooftops blinked through, occasionally indicating their real heights. We stepped into an almost empty shopping mall, and the scene was eerie. The evening drizzle had wet the marble-covered floor by the entrance, making it slippery to walk. The humid air was sticky, and the idea of the virus quietly and invisibly landing on my skin gave me goosebumps. There were two men eating a meal in the corner of the mall’s restaurant, which was otherwise empty. I peeked in while continuing to visualize the virus particles. Two sluggish security guards wandered around with their guard dogs, who looked much more exhausted than their human companions. Everything was slippery, wet, mildewy, and seemingly sprinkled with a dash of boredom.

Now, back in New York, the scene repeats itself. Familiar places here, such as the Fulton Center and Grand Central Station, are hauntingly still and vacant. An Evangelical Christian organization is building a field hospital in the middle of Central Park. New York City is now Wuhan 2.0. It is evident that the unprecedented spread of the virus is a result of globalization. It has materialized and concretized the otherwise imperceptible traces of human mobilization. I manifest this myself, as I may unwittingly be part of the second wave of the virus’s spread. A friend joked that if I had delayed my trip—staying in New York and then traveling to Shanghai—I could have dodged the peak of the outbreak in both places. I guess that is indeed the current strategy of many people with the privilege of international mobility.

As more cases are diagnosed and more people die, the world has finally realized that this is not a “China-specific” event. As the danger looms closer, we want, out of fear and ignorance, to attribute an agency—or a nationality—to the virus. But bacteria and viruses have no agency. They spread blindly and unpredictably where they can, their pathways facilitated by our ever more globalized world.

The Bat

In 2013, I was invited to contribute an essay to the expanded reader for the touring exhibition “A Journal of the Plague Year,” which originated at Para Site in Hong Kong.13 The exhibition and the eponymous book took a deep dive into the history of pandemic-induced racism, xenophobia, and discrimination. The year 2013 marked the tenth anniversary of the SARS outbreak, and of the death of Leslie Cheung, a pan-Asian pop icon and founding father of Canton Pop, whose performance in Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (1997) was famously mesmerizing.

I do not have much of a memory of SARS. That year, in 2003, I was in Shanghai, preparing for the National College Entrance Exam, commonly known as the gaokao, a grueling three-day standardized test that strikes fear into the heart of every eighteen-year-old in China. I was completely exhausted by my studies, but I do remember when Leslie Cheung decided to end his own life by jumping off the twenty-fourth floor of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Hong Kong at the height of SARS outbreak. Leslie had suffered from severe depression, apparently caused by prejudice against his sexuality.

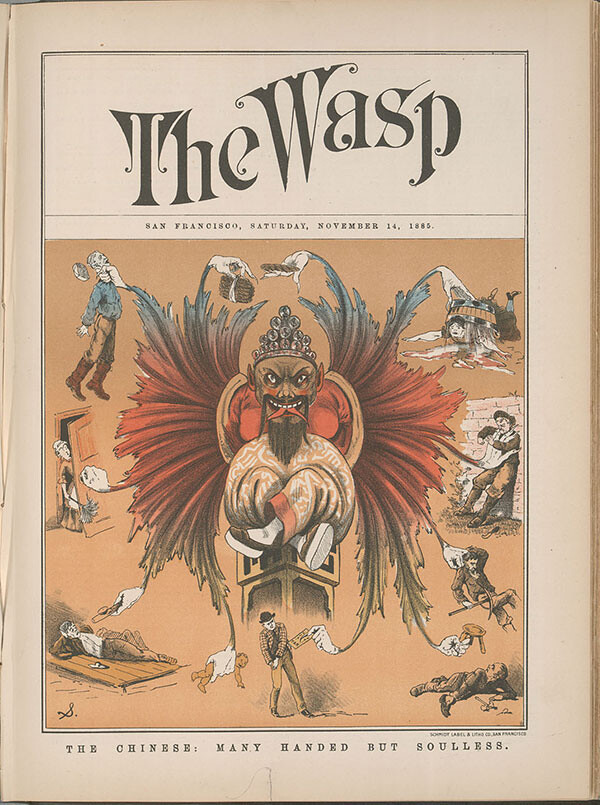

The opportunity to write the “Plague Year” essay allowed me to return to 2003 and explore xenophobia and racism then and since. By 2013, I had lived in California for nearly eight years. Racism had turned from something relatively foreign to me into a reality. My essay took as its starting point the cover illustration of the November 1885 issue of the San Francisco–based satirical magazine The Wasp. The illustration features a winged devil sitting on top of a pillar with its legs crossed. Two tongues stick out of his grinning mouth. His ten claws reach out to offer various vices to an innocent Caucasian figure below. The title of the illustration expresses its message: The Chinese: Many Handed But Soulless.

“The Chinese: Many Handed But Soulless,” cover of The Wasp, vol. 15 (November 1885). The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

I compared this image of this multi-handed monster to a cephalopod, which is often used to represent oppressive and unconquerable evil power. But now, as I reexamine the illustration, the figure looks more to me like a hybrid of a bat, an octopus, and a human. According to recent research on the origins of Covid-19, “In one possible scenario, the coronavirus evolved to its current pathogenic state through natural selection in a non-human host and then jumped to humans.” Researchers have proposed that “bats are the most likely reservoir” of the virus, and another unidentified and “intermediate host was likely involved between bats and humans.”14 Along with this speculation, a video featuring two Asian girls eating a bat dish went viral on the internet when the epidemic first broke out in China.

When the bubonic plague flared up in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1900, the disease was immediately associated with the “immoral nature” of the Chinese community. Already regarded as disreputable, Chinatown became a metonym for plague, evil, and death. Playing on the public’s anxiety over contagion, the negative portrayal of Chinese people found widespread acceptance, which not only dehumanized an entire population but also legitimized the violent repression and removal of Chinese people by local authorities. City officials needed a scapegoat; they also wanted to redevelop Chinatown.15 Since that time, our racial sentiments have not evolved much. History is doomed to repeat itself. As US politicians cross off “Covid-19” in their briefing notes and replace it with “Chinese virus,” we can plainly see that the hybrid creature has returned. It crawls and creeps, spreading its deadly poison.

It is not just politicians. Among the countless all-too-rushed critical analyses by impatient intellectuals, Alain Badiou wrote the following:

The initial fulcrum of the current epidemic is very probably to be found in the markets of Wuhan province. Chinese markets are known for their dangerous dirtiness, and for their irrepressible taste for the open-air sale of all kinds of living animals, stacked on top of one another. Whence the fact that at a certain moment the virus found itself present, in an animal form itself inherited from bats, in a very dense popular milieu, and in conditions of rudimentary hygiene.16

A seemingly factual description and quasi-scientific sketch, drawn in haste from some news images of Wuhan, legitimizes the attribution of culpability to the unhygienic Chinese way of life. Besides the fact that Badiou mistakenly calls Wuhan a province, he makes a specious generalization about Chinese markets—namely, that they’re all virus-generating, unsanitary shit holes. His ignorance is similar to that of the Wall Street Journal writer and editor who crafted the headline “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia” without basic research into the “sick man of Asia” reference and its history, or into Chinese history at large.17 The phrase was a malicious, Opium War–era invention used by the British to humiliate and demoralize the Chinese (the word “sick” was used to describe those addicted to British opium). After facing criticism, the WSJ offered a flimsy defense: they thought the phrase echoed a description “familiar to American readers that cast the late Ottoman Empire as the ‘sick old man of Europe.’”18 Even if the virus initially arose in a Chinese market, its real origin cannot be understood without considering the dramatic ecological destruction that accompanies the rapid expansion of the cities in which such markets are found. This kind of intellectual laziness poses the greatest danger of all.

Wuhan is the name of the capital city of Hubei province. The two girls in that widely circulated video were in the Pacific nation of Palau, not Wuhan, and the dish is a local delicacy that is regularly served.

There is another reference to a bat that constantly haunts me. It is found in the old Aesop fable “The Birds, the Beasts, and the Bat.” The story goes like this:

The Birds and the Beasts declared war against each other. No compromise was possible, and so they went at it tooth and claw. It is said that the quarrel grew out of the persecution the race of Geese suffered at the teeth of the Fox family. The Beasts, too, had cause for fight. The Eagle was constantly pouncing on the Hare, and the Owl dined daily on Mice. It was a terrible battle. Many a Hare and many a Mouse died. Chickens and Geese fell by the score—and the victor always stopped for a feast. Now the Bat family had not openly joined either side. They were a very politic race. So when they saw the Birds getting the better of it, they were Birds for all there was in it. But when the tide of the battle turned, they immediately sided with the Beasts. When the battle was over, the conduct of the Bats was discussed at the peace conferences. Such deceit was unpardonable, and Birds and Beasts made common cause to drive out the Bats. And since then the Bat family hides in dark towers and deserted ruins, flying out only in the night.19

I often identify with the Bats—not because I am a political or deceitful person, but because I am constantly negotiating among different values, as a learned survival strategy. Everything that I’m experiencing now in New York feels like a flashback, but not from a remote time—from two months ago. It’s a strange feeling to witness the same mistakes repeated in such a narrow timeframe: you see that many lives could have been saved if preventative measures were taken earlier; your understanding of individualism, collectivism, and universality becomes destabilized; your feelings about personal freedom and authoritarian control become ever more confusing.

A few Chinese friends and I initiated a support group so we could share information and vent our frustration. The anxiety of being Bats is not felt alone. We have a shared experience of perpetually living between different ways of life, different ideologies, different worlds. A question emerges: How to harvest the energy from such permanent existential untranslatability and transform it into something productive?

Slavoj Žižek, “My Dream of Wuhan,” Welt, January 22, 2020 →.

See the Guggenheim website for information on the exhibition →.

Li Wenliang’s signed and fingerprinted “letter of admonition” is available in the public domain →.

A translated version of the story can be read here: →.There are various ways to translate “mantou,” but I prefer “steamed bun.”

Chenghao Ye et al., “Theoretical Study of the Anti-NCP Molecular Mechanism of Traditional Chinese Medicine Lianhua-Qingwen Formula (LQF),” chemrxiv.org, March 21, 2020 →.

Wang Hui, The End of the Revolution: China and the Limits of Modernity (Verso, 2011), 195–96.

In Xinhua News Agency’s collection of reportage on Xi Jinping’s speeches, this page talks about Chinese medicine →.

See “Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19)” at the WHO website →.

Quoted in Lung-Kee Sun, “To Be or Not to Be ‘Eaten’: Lu Xun’s Dilemma of Political Engagement,” Modern China 12, no. 4 (October 1986), 459–85.

Hou Hanrou, “The Spectacle of the Everyday,” curatorial text for the 10th Biennale de Lyon →.

See the book here →.

Scripps Research Institute, “COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic has a natural origin,” Science Daily, March 17, 2020 →.

Guenter B. Risse, Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012) 1–15.

Alain Badiou, “On the Epidemic Situation,” Verso blog, March 23, 2020 →.

Walter Russell Meade, “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2020 →.

Marc Tracy, “Inside The Wall Street Journal, Tensions Rise Over ‘Sick Man’ China Headline,” New York Times, February 22, 2020 →.

Aesop, “The Birds, the Beast, and the Bat,” Aesop’s Fables for Children (originally published 1919).