“Speak Into The Mic, Please” is an essay series that will be published serially in e-flux journal throughout 2019. Samer Frangie’s “The Little White Dog and the Postwar Promise” is the second text in the series, for which I have the honor of serving as guest editor, and follows Khaled Saghieh’s “1990s Beirut: Al-Mulhaq, Memory, and the Defeat,” which appeared in issue 97.

The title of the series comes from Lina Majdalanie and Rabih Mroué’s performance Biokhraphia (2002), in which Majdalanie speaks to a recorded version of herself that is constantly reminding her to speak into the mic in order for the audience to hear her better.

In a similar move of speaking to the self in front of an audience, the commissioned texts in this series will attempt to look at the conditions of production surrounding the contemporary art scene in Beirut since the 1990s, taking into account the backdrop of a major reconstruction project in the city, international finance, and political oppression, whether under the Syrian regime or under hegemonic NGO discourses.

The various texts will examine the interconnections between the economic bubbles and the political and cultural discourses that formed in Lebanon between the 1990s and 2015. During this period, a number of private art institutions, galleries, and museums popped up in the capital, while the city was buried under garbage due to years of political mismanagement and corruption.

This apocalyptic image—institutionalization paralleling ecological catastrophe—is historically framed around two periods in Lebanon when attempts to construct “optimism” in the country failed: the 1950s, which was the period of nation-state building that followed independence; and the 1990s, which was the period of post–civil war reconstruction, privatization, and “neoliberal optimism.”

The year 2015 also marked roughly twenty years of building the contemporary cultural scene in Beirut. This scene began with artists’ initiatives, public art exhibitions, and a critical discourse that was informed by, among other things, the migration of leftist thought and traditions into the cultural realm at the end of the so-called cold war, when the Lebanese left’s political project was defeated. Where do we stand today in relation to these politics and discourses?

Samer Frangie’s “The Little White Dog and the Postwar Promise” describes the generation in Beirut that grew up during the civil war (1975–1990) and came into adolescence as it suddenly ended. He writes: “We rushed into the future because we had no past, at least no past that could provide us with a sense of belonging, meaning, or continuity with what had come before. We were the product of a rupture, and we became the vanguard by default.” Tracking the generation’s libidinal desires for their present alongside their need to redeem the past, Frangie endeavors to describe the period leading up to the 1998 elections, when in his words, “a certain age of political innocence ended” and the civil war generation became adults.

The origin of this essay series traces back to a project initiated by the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art in 2016. Titled “WDW25+,” the project was an attempt by Witte de With to formalize its archive and to historicize its activities as an arts center. I was invited by Defne Ayas (then director of WDW) and Natasha Hoare (curator) to engage with the institution’s archival holdings related to “Contemporary Arab Representations,” a curatorial project initiated in 2002 by the center’s former director Catherine David. The project involved researching and exhibiting the work of cultural and aesthetic practitioners from various Arab cities, including Beirut.

With this essay series, I do not intend to focus on a specific geographical area, as Catherine David did at Witte de With. Rather, I want the series to serve as a launching pad to tackle broader mechanisms of contemporary art. In addition, my aim is to go beyond the discourses that mystified cultural and artistic projects in the 1990s, shedding light on and undoing certain (liberal) ideologies that shaped that period and its remnants today.

I would like to thank Natasha Hoare, Defne Ayas, Ghalya Saadawi, Tony Chakar, Hanan Toukan, Hisham Ashkar, and Walid Raad—all of whom participated, directly or indirectly, in the conversations surrounding my Witte de With project, and some of whom will also contribute a text to this series.

—Marwa Arsanios

We did not realize it at the time. But in hindsight, the nineties ended in 1998.

We did smell something of that end in June of that year when the first municipal elections after the Lebanese Civil War (1975–89) took place. The campaign calling for the organization of these elections was one of the high points of civil society activism in the nineties, fueled by the hope that local elections would provide a more transparent form of political representation, one that expressed the true will of the “people.” Emerging from the destructive civil war, the hopes were that its wounded citizens, having lived through the madness of sectarian violence and its ideological follies, could form the basis for a democratic, civil, and peaceful political society. Municipal elections appeared as the best crucible for the rebirth of this promised citizen, and civil society actors latched onto it. The elections we called for took place, but the results were disappointing. The postwar elites reproduced themselves at the local level, the supposedly more transparent level, subverting our hard work of advocacy. We did not expect revolutionary change, but it was still a disappointment, and we sensed that the problem was not in the particularities of our forms of political representation or in their techniques, but in what was being represented. The wounded citizen was too wounded to form any credible political force. We could smell that the promise of a movement of popular discontent was faltering.

The hot and humid Lebanese summer has its own share of smells, and we quickly forgot the particular smell of that electoral disappointment, until November of that same year. The election of president Émile Lahoud was a political turning point for the country, setting it on a path of growing strife and violence. But for us, it had a different and more personal taste. It represented the shattering of our unified oppositional stance. Lahoud came to power on an anti-corruption platform, backed by the Syrian regime and the growing security apparatus in Lebanon. His political platform was opposed to the economic project of the late prime minister Rafiq Hariri (in office from 1992 to 1998), the chaperone of the neoliberal restructuring of postwar Lebanon. Cracks started appearing in what seemed a unified system of rule based on an alliance between an authoritarian wing and a neoliberal one—cracks that took the form of a choice we were forced to make: to stand with anti-corruption authoritarianism and its explicit violence or neoliberalism and its more implicit violence. The fiction that we could oppose a “regime” from a position of exteriority ended, and with it the idea that we could redeem from the past a coherent and consistent program of opposition, one that could be an alternative to the postwar regime.

All that remained from that prior position of assumed exteriority began to normalize that year. The critical discourses that emerged in the postwar moment were slowly becoming institutionalized, sanitized, depoliticized, and were losing their critical edge. The “memory discourse,” or discourse about the civil war and the mode of remembering it, started to form its own institutions, funders, entrepreneurs, and rituals. The emerging local scene of contemporary art was discovered by the global art market and shifted its gaze toward the outside world. The hesitant yet potent network of nonstate organizations became NGOs, and started their descent into the solipsistic world of budgets, proposals, and funding. The position of exteriority was now professionalized, normalized—in other words, depoliticized.

A certain age of political innocence ended in November 1998. We became adults.

***

We were not always adults, even if it often felt so.

We were a generation, born roughly between 1975 and 1980, conceived in the beginning of the civil war. Our childhood unfolded with it. The war was all that we knew, and, like children anywhere, we made the best out of it. It is hard to say whether it was fun or not, but the exceptionality of life in a war-torn country marked us. At some point during the nineties, when gonadotropin-releasing hormones were triggering our pituitary glands, the war ended suddenly, after some of its most violent episodes. Fueled by estrogen and testosterone, we welcomed the nineties and their promises, as they corresponded to our libidinal changes. There was an uncanny synchronicity between our internal transformations and the world around us. We were entering new phases in our lives, and so was the country around us.

But we did not have time to enjoy this synchronicity; or to be more precise, this synchronicity imbued our teenage years with a gravity that was too much to handle for our hormonal changes. We were suddenly rebranded as the postwar generation, the first after the cataclysm. In a span of a few months we became “victims of the war,” our childhoods described as traumatic, our past an evil against which the present had to inoculate itself. At the exact moment that the war ended, we had to relinquish our youth, now tarnished by war’s memory. But we were not simply teenagers without a childhood. We became the generation that should redeem the past of violence in a future to come. We became the human embodiment of the postwar temporality, a temporality for which the present was nothing but a laboratory that could transform a remembered past into a different future. We were the perfect guinea pigs for the postwar promise.

We were not alone waiting to inherit the earth and its present. The war was a rupture, a break in the lives of all those who lived through it, a rupture that called for its suturing. The nineties became an intense moment of intergenerational transference between a prewar and a postwar generation. But generations are loose categories; maybe a better way of putting it would be to say that it was an intense moment of transmission between a prewar sensibility and a postwar one, brought together by the shared yet different experience of the war. It was also a moment of competition as to what experience was to be redeemed: that of an older generation of intellectuals, artists, and militants, who drew the contours of what the postwar promise would be. Displaced by the war and its violence, having undergone a process of self-criticism for the ideological follies of their youth, this generation saw the postwar era as the moment in which their narrative of self-redemption would become the “official” story of the war, their experience the resolution of its drama. Like our parents, they suffered through the war, made sure we survived it, and had reached the stage when their efforts were to be rewarded. We looked at the unfolding postwar present neither with the shame of the perpetrator nor the innocence of the victims, but rather with the guilt of the surviving child. We inherited that entire generation as additional parents and we succumbed to the guilt that came with such a displacement. We learned to swap our acquired memories for their appropriated ones. The present would have to wait until their past was redeemed. We were coming of age in the nineties, but we were coming into their age.

***

Back to 1998.

At first, we felt it as a temporal tremor, caused by the loss of the “future” as a category. For the postwar period was not merely an era defined by its state of coming after the war. It was a promise, one that may have only lasted a few years, but a simple promise nonetheless that the future would be different from the past of war. It seems strange today to say that we fell for a promise of the future. After all, the nineties, despite all its optimism, was a post-ideological moment, one whose global mantra was that “there is no alternative.” It was a time hardly conducive to a utopian imagination, and we were suspicious of any claims made in the name of the future. But when it collapsed in 1998, and the bareness of the future reappeared, we realized that we did fall for this promise.

It may be a cliché to say that the past, from the perspective of the present, looks like a field of ruins for the historian to excavate. But our past, then, was literally a field of ruins, not for excavation, but for reconstruction and pillaging. We emerged from the civil war into a violent reconstruction process, governed by a postwar settlement that was characterized by “state-sponsored amnesia,” and a genuine desire to forget past horrors. We rushed into the future because we had no past, at least no past that could provide us with a sense of belonging, meaning, or continuity with what had come before. We were the product of a rupture, and we became the vanguard by default.

We had no past in the sense of historical continuity, but instead had much salient discourse on the need to keep its memory alive. The past was no longer a stretch of time to be overcome, but rather a narrative field through which an alternative future could be reached, or at least imagined. Different organizations and campaigns made sure that by the end of the nineties, memory had become the hegemonic theme in the postwar cultural sphere. The polyvalence of the concept of memory allowed it to unite the various critiques of the postwar regime on a unified plane, replacing previous concepts as the organizing principle of political action, such as revolution for example. Against the tendency of the present to erase its past, or what was seen as the amnesia of the present, the capacity to remember became the political gesture par excellence during the nineties in Lebanon. Witnessing, remembering, excavating, archiving, commemorating, resisting erasure—these constituted the toolkit of our militancy. It was the antidote against the violence of the past, and the plane on which the sectarian divisions could be resolved. It was also an ethical and political imperative, one that opposed the postwar amnesty in the name of the innocent victims and bystanders of the civil war. But it also provided the cornerstone of the opposition to the reconstruction project, seen as the urban manifestation of the politics of amnesia. And in a global order bent on erasing the struggles of the past, it became the mode through which solidarity was to be expressed.

It was the past’s redemptive force that was at stake. The slogan of the real-estate company Solidere, tasked with the reconstruction of Beirut, was “Beirut Madina ‘Ariqa lil-Mustaqbal” (Beirut: An Ancient City for the Future), which captured this interplay between past and future. But this interplay was not limited to the imagination of professional marketing consultants. A landmark conference on the memory of the Lebanese Civil War, held in Beirut in 2000, was entitled “Zakira lil-Mustaqbal” (Memory for the Future). With the rupture of the war behind us, political positions were staked on a similar plane, that of the past as future.

In 1998, the past was losing its redemptive power, with the future being the first category to fall. The liberal synthesis of the post–Cold War moment, the ideology that was supposed to subsume all previous ideologies, was held together in our post–civil war context by this temporal promise. The democratic citizen was the citizen who learned the lessons of the civil war. The critical intellectual was the intellectual who survived the war through their ideological self-criticism. The desired political system was that which broke the cycle of violence of civil war. This liberal synthesis, which recoded political causes in a normative language, was the political translation of the temporal orientation of memory. The civil war was to be the past of a liberalism in search of a history.

All we had left was the present. But we had been raised to despise presentism, or the tendency to prioritize the unfolding present over its historical determination or future realization. The present was to be suspended in the name of promised economic growth, the reconstruction managers told us. The present was to be suspended until we got our history right, replied the critical intellectuals.

***

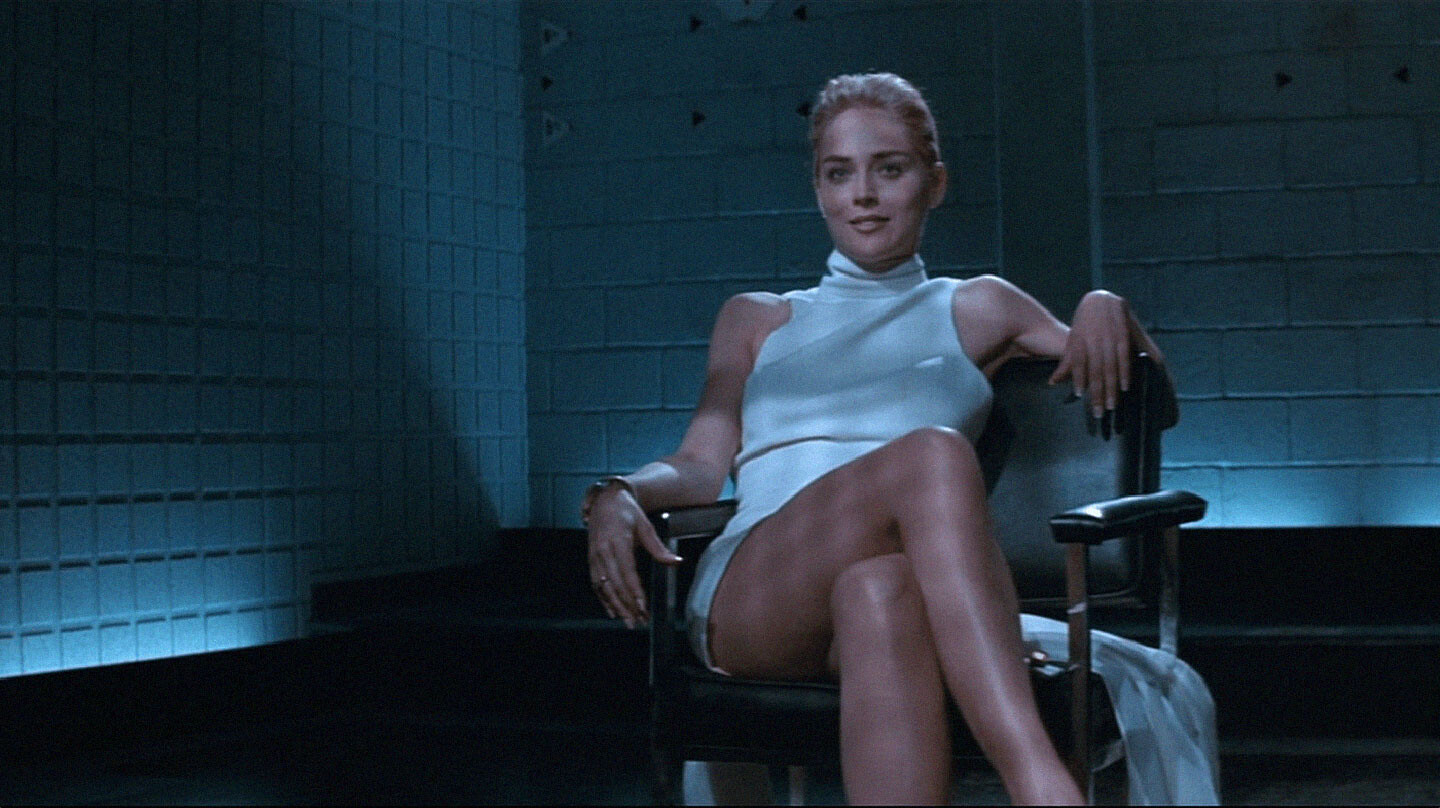

But the nineties were not always like that, at least for us, especially during the influx of gonadotropin-releasing hormones. The decade started for us when Sharon Stone uncrossed her legs in Basic Instinct, offering us a fleeting glimpse of the promised pleasures of the new world. The year was 1992, the civil war had ended two years earlier. We drove for over an hour to Jounieh, a seedy Christian area outside of Beirut, to watch the uncensored version of the film. At that time, the Christians, despite having lost the war, were still the guarantors of a laxer policing of sexuality. We did not realize then that the movie prefigured our binary temporality, a buildup and a resolution around a fleeting scene, a fleeting present. The scene, despite its evanescent and ephemeral feel, was important, it was the reason why we drove for an hour. And it was the reason why the movie was censored, a decision that made this now absent scene more titillating, more concrete, its dangerous appeal now guaranteed by the real power of the censors and the postwar state’s changing moral apparatus. In a way, the nineties were akin to the censored version of Basic Instinct, a past buildup and a future resolution around a missing present.

Still from the movie Basic Instinct (1992).

In 1992, we were slowly discovering the interplay between these libidinal pleasures and the structure of censorship and transgression. Three years later, a blurry homemade sex tape, involving the former Miss Lebanon, Nicole Ballan, was leaked and widely circulated among the public. The two protagonists, according to the prosecutor, “displayed their sexual organs without any clothes or shame.” The prosecutor must have had a better version of the tape than us, for we had to try to decipher this absence of shame from the blurred and grainy copies we could get ahold of. Absence is very hard to spot on a poor-quality VHS tape.

It was not what was displayed that shocked the prosecutor, but the act of display itself: the taping and consumption of sex for visual pleasure. The Ballan tape was not simply about sex, its documentation or registration in the public sphere. It was a tentative assembling of different processes that were at work in this postwar period, from the reconfiguration of the technological and visual landscape to the transformation of the underlying sexual and moral order. The tape challenged us, in our structure of pleasures, our desire to see, our need to transgress. It pointed to the imbrication of technology, law, and power in the formation of selves, and it highlighted an emerging dimension of the present. It was not simply the tape that interpellated us; it was also the underlying transformations in the moral order. We could witness the city changing, new practices emerging, new subjectivities developing—the tape in a way was all of that. This was a present that was unfolding, a present that had a thickness that could not fit into the emerging ideological discourse of the postwar period, a thickness that we seemed to access only through our libidinal pleasures.

The prosecutor saw all of these questions, but we did not. Or we could see them, but we could not yet make sense of them. All we could see was a small white dog who wandered casually into the frame, who the newly reorganized media assured us “was not involved in the sexual choreography,” though he was at home in this unfolding present. We saw the dog but we could not really see it. Instead, we were inhabited by the vision of imagined hordes of wild dogs rumored to have haunted the streets of war-torn Beirut. The present was a small white dog, more at home in a sex tape than in the ravaged downtown of the capital. We looked at the tape, but quickly turned our gaze from it. We had a war to remember. Or that’s what we were told.

***

We could have followed the little white dog wandering into the frame, instead of remembering the packs of dogs roaming the streets outside. But we did not, and from the perspective of these wild dogs, the postwar present did not make sense; it was out of joint, as the saying goes. For a temporality structured by the imperative to remember, the present could not be grasped, should not be allowed its thickness and reality. For the intellectuals of the postwar period, the members of this older generation, the present was experienced as alienating, absurd, unreal. The suddenly imposed peace made no sense, old rivalries turned into new political alliances, ideological oppositions softened and were replaced by pragmatic rhetoric. The ambitious reconstruction project added to the reigning sense of alienation from the new.

The disjointed character of the present was only salient for those who previously believed in a certain joint-ness of time, only to be violently disillusioned by the war, left to roam the streets of Beirut without any ideological guidance. In other words, it was out of joint for the postwar cultural intelligentsia, which had largely emerged from the leftist experience of the sixties and seventies. The defeat of these leftist forces had driven many among this intelligentsia into a state of epistemological crisis. The present was alienating to them because their past was one of disillusionment. Hence the present called for redemption, for a future that would redeem this disillusionment. With redemption came austerity; there was something austere in this critique of the present, a critique that understood its affective basis in terms of gestures of withholding, resisting, sacrificing, and foregoing. The danger was succumbing—losing this position of self-imposed exile, seeing the present for what it is.

The cultural discourse of this intelligentsia became centered around a new figure, the outsider: the exilic individual who returns after the war, the alienated subject who cannot make sense of things, the silent observer who tries to document the unfolding present. The outsider, always a man, replaced the militiaman as the figure exemplifying his time, a move that paralleled the passage from war to postwar Lebanon. Marginality was redefined as epistemological; it was a question of understanding, or its lack, rather than of justice or belonging. Outside critics could not understand the present; their simple, yet false, naivete was the guarantee of their sanity amidst this absurd time. The politically committed intellectual gave way to the epistemologically alienated one.

Epistemological alienation, weak liberalism, and a temporality structured by memory formed the basis of this postwar critique. Its history was provided by a certain history of the Lebanese left, one that was recoded through the liberal prism of memory, to become the history of the victims of the civil war. The left was imagined to be the secular other of the sectarian war, its modern residue; it was the cause of the civil war and its casualty, the misguided perpetrator and the innocent victim, the rebellious son of the system and its inheritor, the marginal political player yet dominant cultural pole, the critic of liberalism and the crucible for the emergence of the modern citizen. It was not a left of the present, but a left waiting to be redeemed in this present.

We started the nineties libidinally attracted to the present, viscerally welcoming its transformations and, as teenagers, yearning for our own self-transformation. But we learned to withhold and not to succumb to such impulses. The white dog was not compelling enough, was not serious enough. It could not resist the guilt that came with the postwar critique and its desire for redemption. It could not resist the guilt of the surviving child when faced with the desire of their wounded parents for redemption. Propelled by this guilt, we succumbed to a nostalgic yearning for an old Beirut we never knew, to see our present as a bad repetition of theirs, to see the future as their repetition. The memory of the civil war became a trap akin to a catch-22: The past was the golden age but the past brought the war. Their generation was the greatest generation but it could not resist becoming a victim. And before decoding this uncrackable riddle, we could not see Ballan’s tape nor the new realities it brought forth. The little white dog had no chance against the horde of roaming wild dogs.

***

And then, one day in 1998, while we were busy remembering, the postwar ended just as suddenly as the war had eight years before. We did not realize it then; we persisted in our mission to archive the past. But something had ended. And we gradually began realizing that our newly acquired political vocabulary was becoming quaint and irrelevant, its concepts sounded hollow, floating without any grip on the present. We were no longer the postwar generation that would redeem the past, but merely the last generation to be defined by this event, subsumed by it, exhausted by its memory. Others came after us, for whom the war was a distant past. Others came and looked at us as refugees from history, the last generation that remembered what gunshots sounded like. From a vanguard, we became a generation of mourners, the last generation to mourn the twentieth century.

With time, we also realized that what we were trying to redeem was not simply a prior generation, but their hubris, the hubris of those who spoke of marginality but never stopped seeing themselves at the center. We were the last ones to labor with a form of critique that shied away from “otherness,” that could still ignore “otherness,” content with reducing all differences to the secular other. Ballan’s tape invited us to explore the manifold instantiations of power, its capillary reach, its affective subterraneous structures. But we, like our forbearers, preferred the battle for the center, still believing in the redemptive character of power, still attached to the fiction of a counter-hegemonic project that considered marginality a temporary location from which the battle for the center would be waged. We maintained the fiction of an oppositional stance, which with time started looking more and more like a form of blackmail, the blackmail of the male Arab intellectual.

I often wonder what would have happened if we had followed the little white dog back in 1995. Maybe if we had, we would now be able to look back at the postwar period as the past to today’s present, instead of seeing it as the overflow of a historical period that has long ended. Maybe if we accepted then that our connection to the present is mediated through different affects than those of guilt and melancholia, we could have had a richer connection to it, one that would have questioned the centrality of this experience of alienation. And maybe then, we could have understood intergenerational transmission according to a different model than that of the inheritance of loss and the reproduction of intergenerational guilt. We would certainly not have been at a loss as how to think critique differently, struggling with the question of its immanence.

Instead, we find ourselves writing to end this period, fighting battles with our forbearers to put an end to that chain of transmission, to allow for something new—that does not include us—to emerge from the weight of the past. Facing this new, we stand in silence; we are not part of it, we belong to a period that has now ended. And we face this intergenerational transmission without guilt. The guilt of the surviving child cannot be bequeathed. We have nothing to bequeath. Rather, we are still inheriting, now from those who came after us. We are inheriting their present, sometimes intruding on their present, to rediscover our past, a different past, the past that we could have had. It is not guilt that moves us, but rather a certain gratitude for the passing of time and generations, one that can lay to rest all the hordes of wild dogs.

Category

Subject

I wish to express my gratitude to Marwa Arsanios, Zeina Halabi, Sara Mourad, Andreas Petrossiants, and Khaled Saghieh for their insightful comments and suggestions.