Once Removed: Screening and Conversation

Takeover: Online discussion with May Adadol Ingawanij, Riar Rizaldi, Ephraim Asili, Tiffany Sia, and Sriwhana Spong

Online discussion with May Adadol Ingawanij, Ephraim Asili, Tiffany Sia, and Sriwhana Spong

Summa Technologiae online conference

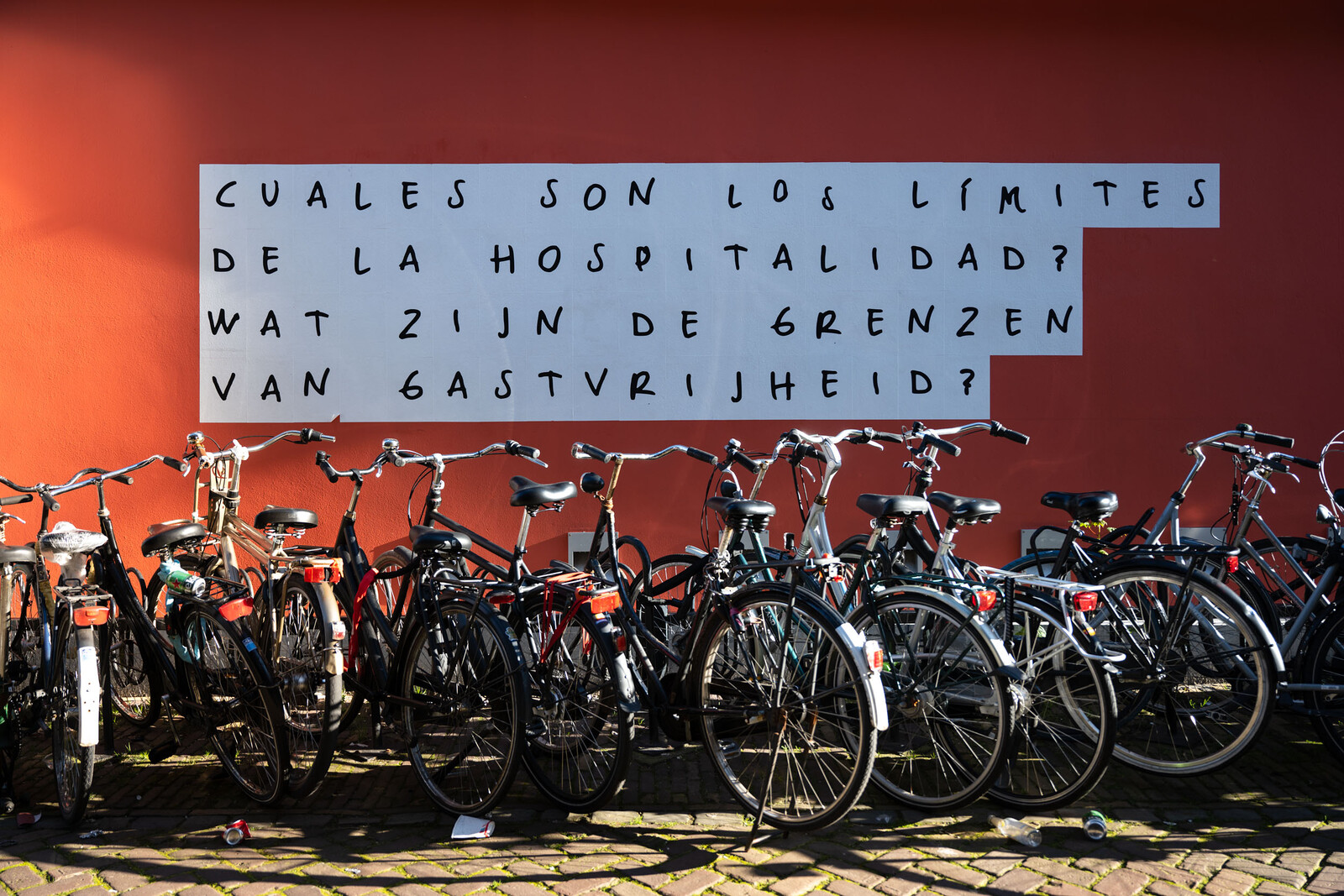

I agree with the above critics that these artworks create spectacles out of non-Western cultural practices, and that there are dangers in bringing rituals into the art space. Yet I am also concerned with how the criticism reflects limitations of translation, as these limitations will always mislead us into interpreting these artworks as exercises of spectacularization or performance, corrupting the essence of the ceremonies. In using translation as a tool to understand the unknown, what potentialities are we missing?

To hear “rightly” is to register acoustical rightness or trueness not only by means of forensic acoustics, or by moral criteria of right and wrong, but according to measures of rhythmic beauty (euruthmoi) and mellifluous accompaniment. “To accompany” (akoloutheî means to follow or to flow from) lies at the heart of what Plato, in the Republic, identified with the poetic. For Plato, just as matter must follow soul, so musical harmony and rhythm must follow poesis. Good rhythm in this sense accompanies, agrees with, or “goes along with” fine speaking. For Plato, making a “right” republic necessitates allowing the superior register to lead, and ensuring that its accompaniment be a good match.6 We could say that Plato gives us the “good match” theory of just translation.

WEB.jpg,1600)