In her poem “The First Water Is the Body,” the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Natalie Diaz describes the temporal-physical gap that cracks open when attempting to translate the Mojave word for the Mojave people into English: “We must go to the point of the lance entering the earth … We must go until we smell the black root-wet anchoring the river’s mud banks. We must go beyond to a place where we have never been the center, where there is no center—beyond, toward what does not need us yet makes us.” 1 How might one translate a proper noun, that is a phrase, a contour, a geography? In the poem and in her larger body of work, Diaz approaches the problem of translation like a story without a beginning or an ending, a “third place” that maps the challenges of fulfillment on the page. In a podcast interview about her collection Postcolonial Love Poem, Diaz noted, “I’m slowly learning, not how to make Mojave exist in English but to give Mojave a place within this other language that it can’t be touched.” 2 To translate then is also to make space for non-translation and to explore the possibilities of an infinite in-between. In A Manifesto for Ultratranslation (2013), Antena Aire, a Houston- and Los Angeles–based language justice collaborative, reimagines the space of un-translation as ultratranslation, or the activities that occur in the asymptote, where embodied states of visibility and resistance arise: “No matter how close we try to get, there’s always a space between the two—any two—and that is the space where we live. The space where we transpose or are transposed.” 3 Thinking beyond translation as a means of rationality or legibility, Antena Aire imagines ultratranslation as the movement toward a hopeful impossibility.

A positive tension between hope and failure informs the pedagogies of collectivity at the center of “Ultradependent Public School” (UPS), an immense matrix of thematic curricular nodes, trainings, and works on display that has inhabited BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, this April and May. Co-organizers Clara Balaguer, curator of civic praxis at BAK, and Jeanne van Heeswijk, a Rotterdam-based artist whose practice explores forms of self-organization, have mapped the communal coordinates and social spaces of a school “with, within, and against” BAK’s institutional ambit. 4 Borrowing from A Manifesto for Ultratranslation, the organizers have envisioned the limits of an asymptote as the porosities or margins of an institutional frame: dependent on BAK’s infrastructure and largesse but determined by its own agency, UPS has sprung forward like an epiphytic plant—an orchid, a moss—that grows laterally around an existing structure and whose delicate tendrils slowly nourish themselves from a “shared ecosystem.” Informed as well by social justice, anti-capitalist, and anti-patriarchal collaborative practices, UPS (the program, the structure, the idea) understands knowledge sharing as a form of public-making and a real-time opportunity to “learn what we really, really need to enact the world that we really, really want.”

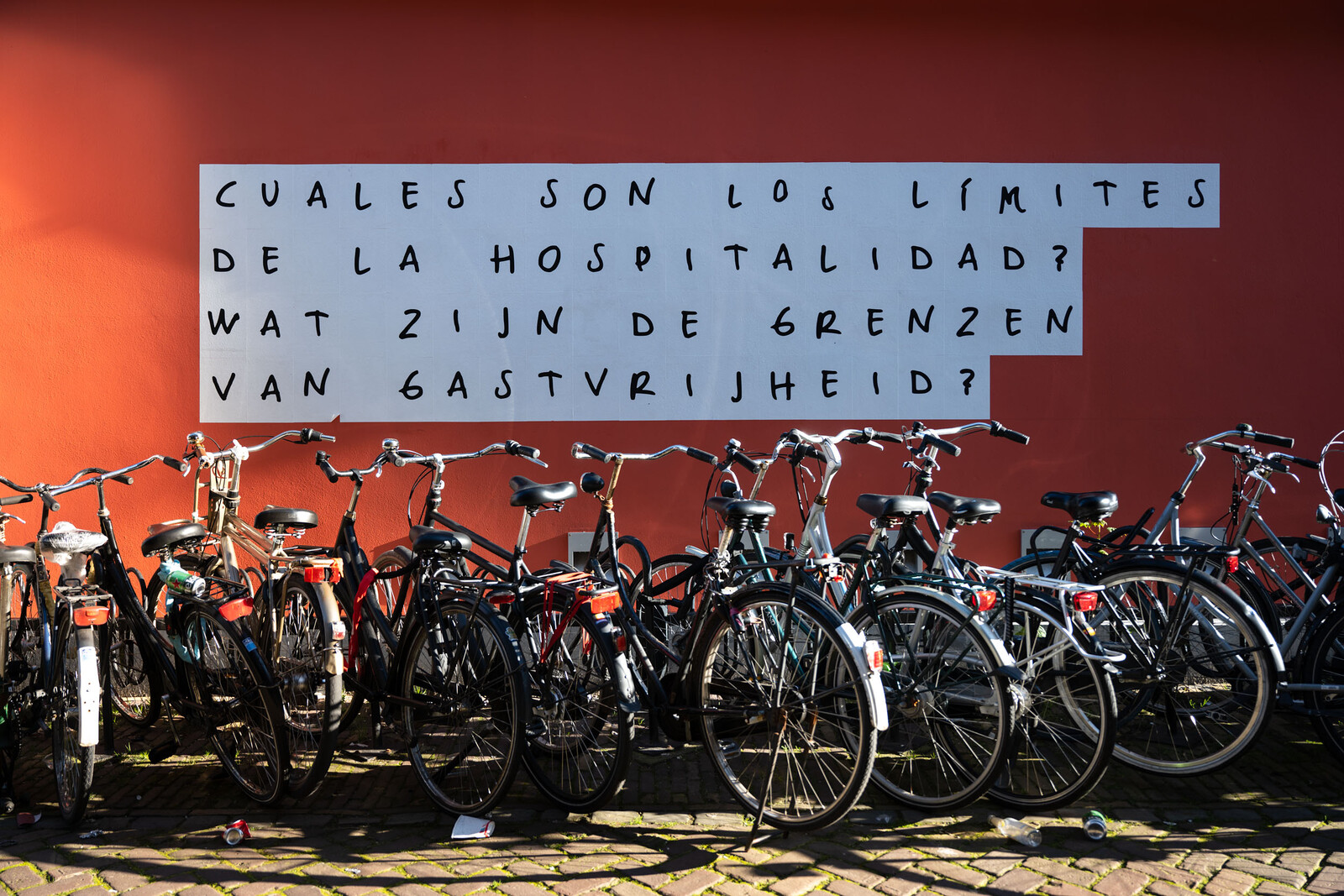

The prefix “ultra,” defined in A Manifesto for Ultratranslation as “beyond, on the other side, indicating elsewhere … surpassing, transcending the limits,” corresponds with the size and scope of the program at BAK, as well as its emphasis on improvisation, cross-referencing, and alternative formulations of learning together (in the place of the workshop, the training; in the place of the exhibition, the “learning object”). The “ultradependency” in the school’s name could be understood as a practice of bolstering and celebrating these approaches to learning together. There’s a kinetic potential across the program: something is always about to happen, which guides a trajectory at once recursive and centrifugal. UPS’s layers of programming resemble a tessellation fitted together at different angles (in urban space, on online platforms) and intended to grow beyond UPS’s two-month duration. Balaguer and van Heeswijk have invited existing collectives and collaborations to lead trainings based on their specific local practices (such as the bookstore and social platform Ulises Philadelphia; BB Workshop at Gerrit Rietveld Academie and Sandberg Instituut, Amsterdam; Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin; and Hong Kong-Mainland Relationship Repairment Study Group, to name only some) and initiated first-time pairings of individual contributors (for instance, the artist and Jesuit priest Jason Dy SJ joined end-of-life doula Staci Bu Shea to explore care work and mediumship in Utrecht and the Philippines). These “faculty” collaborations have informed existing and new work within the study nodes Ultrahospitality, Ultrastudio, Ultraemergence, Ultracirculation, Ultradistro, Ultranslation, Ultraspirit, and Ultramethod, which guide participant interactions within the UPS curricula, the works exhibited, and the world beyond.

While the concept of ultratranslation imagines gaps in meaning like the expansion and compression of a diaphragm, UPS’s fragmented yet ever-expanding program might be better understood as an unexpected inhalation between words in a sentence or an interjection in a conversation that takes it in an entirely different direction. Balaguer has described the networks of collaborations around UPS as an infrastructure with roots, one that “connects you to a biosphere or a community or a society in motion.” This notion of infrastructure is certainly not new to arts programming or social practice, but in UPS there’s an emphasis on the redistribution of resources, time, and skills not just through pedagogical formats but impromptu classrooms. This redistribution is presented as a necessity and a responsibility. Cutting through UPS’s sometimes lofty language, the trainings themselves—which I started thinking of as geographies of dependence—often produced surprisingly straightforward, subtle, and even quiet moments of collaboration, such as composing ikebana arrangements, discussing as a group the role of gossip in work and creative life, or carefully producing an intricate textile out of carved stamps. These actions coincided with another understanding of translation: silence. In Anne Carson’s essay “Variations on the Right to Remain Silent,” the poet and translator writes of a word that intends not to be translated, “a word that stops itself.” 5 Silence here is metaphorical but also forms an intimate bond between the original speaker or writer and their use of language; consider Homer’s acronymic “language of the gods” and Joan of Arc’s metaphysical descriptions of hearing voices that were written into the record of her trial for heresy. In the context of UPS’s sweeping program, I found moments of collective intimacy—working alongside others on an individual project or taking in the sights and sounds of the city with others nearby—as producing more human-scale engagements with the school’s sweeping program and ideas. While silence is certainly a form of resistance, one in line with UPS’s own arrangement of sites of communal learning, the program seems to privilege busier expressions of collective learning: facilitators often worked together, attending each other’s trainings and connecting trainings to adjacent practices all while crafting, eating, and socializing. While the stream of overlapping and regularly updated activities encouraged a kind of fluid intimacy, it wasn’t necessarily clear who was the “we” participating in the programs or the “you” visiting the space that were referred to in UPS’s introductory text. 6 Is this an outsider who encounters UPS and joins the events, the intimacies, the web of interactions, or someone already assumed to be a welcome part of them?

UPS organizers also highlighted the interplay between the epiphytic being and its surrounding environment or genealogy. This genealogy is firstly an acknowledgement of BAK’s set of collaborative working practices and the earlier projects led by van Heeswijk that made UPS possible. Genealogy is also given an expanded definition, one that denotes access to the space and program, as well as the maintenance and care work done in real time (documentation, photography, references to other practices) to sustain the school. Epiphytic UPS attaches itself to this genealogy, making accessible to a public a school that is fitted around and between the outlines of an art institution. UPS situates public learning and public-making (what Balaguer calls “publishing”) as a critique of more extractive institutional frameworks and is interested in translating BAK by repurposing and renaming it: the auditorium has become the gymnasium and cafeteria; the classrooms develop in the exhibition space, which are also activated “learning objects” (van Heeswijk’s preferred term); instruction-like printed ephemera is posted on the walls; and faculty move between curricula and trainings. The school too is transposed from a site of hierarchical knowledge production into a constellation of fragmentary parts that, much like the “ultra-” prefix, are dependent on adjacent or preexisting formats, spaces, and ideas. The terminology used in UPS, notably the description of the program as a “schoolhouse,” carries a light pejorative and references an age-old authority that is never adhered to. A sense of resistance or refusal to conform has permeated the program more generally. This might best be seen in how UPS has inhabited the space: one enters BAK through multiple interlacing works (a soaring plant arrangement by Jason Dy and banderitas designed and carried through the streets by Czar Kristoff and participants) and encounters a stream of activity within and outside the trainings, with groups arriving and departing throughout the course of scheduled sessions. UPS’s interest in democratized access—to an art space and to its works on display, many of which were available for affordable purchase—highlights a kind of nuts-and-bolts transposition of BAK into a space of exchange, even commodification.

BAK’s own history of research-focused projects and fellowships over the past decade has reconfigured the institution as a space of critical knowledge production and a refuge amid dramatic political, cultural, and environmental change. At least in the Netherlands, BAK has become the leading model of an institution as an assembly point for new theoretical positions and artistic practices of resistance. While BAK’s programming has long privileged discursive formats like the lecture, congress, symposium, and publication, UPS has hewed more closely to van Heeswijk’s interests in reimagining narratives of space and belonging through large-scale collective action. While not explicitly noted, UPS’s conception of a school also appears to follow bell hooks’s theories of radical pedagogy, with their understanding of education and in particular (classroom) teaching as sites of collaboration and liberatory practice. 7 UPS’s structural antecedent is “Training(s) for the Not-Yet,” an exhibition and series of trainings at BAK in 2019–20 initiated by van Heeswijk and others to explore alternative ways of forging bonds of trust through community-to-community workshops. Collectivity in both projects is a fundamentally political approach to learning together, as well as an enlightened response to a kind of ambient though nevertheless urgent sense of instability seeping into the margins of the present moment. For UPS, urgency has also informed the framing of collectivity within what organizers call “ultrasectionality,” or an expansion and activation of intersectionality into a “form of understanding and a site of work that must occur in common.” In the spirit of Ultratranslation’s refusal to “reduce the irreducible,” UPS has seemed to defy straightforward summarization. At the time of writing, the program has involved more than 120 contributors who have developed activities and initiatives in the form of radio transmissions, bookmaking and printing, dance trainings, urban monument making (remaking and unmaking), collective tapestry printing, graphic design skill-sharing, and processions through the streets of Utrecht. That new nodes might emerge during these collective sessions or new participants might join the faculty roster demonstrates an impulse to constantly rethink and reedit existing educational structures and references.

In tracking interlocking themes or forms, I found it helpful to return to the idea of geographies of dependency, and in particular physical, often minuscule landscapes like a stitch or a flower petal. In their training “Tales of Symbologies, Here Then, Now There,” the artists and designers Hussein Shikha and Sadrie Alves explored the visual and topographic language of carpet weaving, drawing on Iraqi and Brazilian weaving traditions to produce a collective tapestry of symbols selected during walks through Utrecht. The individual symbolic elements these tapestries brought together formed not only new symbologies but also highlighted the artists’ interest in decoration as creating a disruptive genealogy of a particular place or tradition that may have been forgotten or destroyed. Shikha, who was born in Iraq, is particularly interested in weaving practices from the country’s marshlands, which were largely decimated by Saddam Hussein in the 1990s to eliminate insurgent hideouts. Throughout the space, Shikha’s own textile work was used for pillowcases and tablecloths, again creating a decorative genealogy that spanned great distances and the time that passes between a training or lunch. Decoration then became both a practice of addressing tradition and conflict and a ubiquitous part of everyday life. The decorative could be understood as the most dominant form of dependency or connection in UPS; not only do decorative forms tie symbolic or material elements together, they might also create more complex or even imperfect ways of being together. In their workshop, Shikha and Alves referenced Anne Carson’s description of the adjective, the most decorative part of speech, in her Autobiography of Red: “Adjectives seem fairly innocent additions but look again. These small, imported mechanisms are in charge of attaching everything in the world to its place in particularity.” 8 The adjective, like decoration, is a “latch of being” that produces a fuller spectrum of meaning, one that takes up more space on the page and also produces simultaneous and perhaps contradictory interpretations. 9 UPS, with its interconnected yet sprawling program, embodies the characteristics of the adjective: connecting but also complicating.

Decoration in the built or natural landscape and as a form of protest recurred in other trainings as well. The artist Glenda Martinus makes work imbued with pedagogical processes, which reflect her own experience teaching typing for many years in Curaçao. Her series G.U.T.S, hung across the entire back wall of the exhibition space, is a collection of shimmering geometric renderings of the architecture, flora, and history of Curaçao made using Microsoft Word 97. In the training “D.A.F.O.N.T.,” led in collaboration with the designer Jeanine van Berkel, Martinus shared her unique mediation of a potentially nostalgic form of computer technology to explore what artist and designer Ece Canli has called “monstering”: the production and dissemination of radical aesthetic forms and experiments that have often been dismissed as kitsch or embellishment. 10 Martinus’s own monstering was reformatted as a teaching method and a skill to translate technological nostalgia into storytelling. Martinus’s work and training with van Berkel also highlighted a focus throughout the program on how collective and vernacular design practices might challenge the engrained modernist hierarchies that have long accompanied the discipline and its teaching. UPS’s graphic identity, with its wild use of bold type, is one manifestation among a series of other collaborative graphic design and printing workshops. Recent critical discussion has focused on the access to and democratization of design tools and the threat this poses to the practiced work of professional graphic designers. While these discussions raise important questions about labor, creativity, and compensation, they have also tended to double down on the “right” way to make design work, one that unsurprisingly depends on references to illustrious European male designers of the twentieth century. Balaguer has been part of the reframing of graphic design as a collective practice that questions how and what tools should be used in the creation of a work. 11 UPS, with its embrace of fast and big graphic design projects, established a point of access to unconventional tools (an alternative font catalogue, for instance) and a collective environment that normalized their use. Martinus’s own work, blown up and printed on scented light-pink paper, prominently presided over her training, constructing a different genealogy of design, one that celebrates forms of experimentation that reside on the edges of familiar technologies.

Engaging in all of UPS’s expansive offerings presented a challenge in itself (even following the schedule required skill). While the program was perhaps not intended to be experienced in full, the question remains whether the school was meant to be a somewhat improvised exploration of collective learning or a project that actually realized or enacted a space of ultradependent education. In other words, was UPS the performance of a school, or the construction of an actual organization for collective learning, and if so, who is that school for? The notion of publishing as a form of public-making allows for the act of creating and distributing work to find its own natural lines of communication and community through acts of collaboration. But because the work being made in UPS largely unfolded within the premises of BAK, its possible public was rather self-selected or selective. This inward-facing constituency seemed to point to the program’s conceptual preoccupation with how to construct a school for collective learning instead of the public-facing realization of such a body. Indeed, the emphasis on the form of the epiphyte underlines UPS’s primary interest in the characteristics and power structures inside an institution. Balaguer pointed to the example of the balete tree (also known as the strangler fig), an epiphyte that nests in trees, as a helpful image of UPS’s transient dependency: “Its leaves and foliage grow vigorously upward and its root structure vigorously downward, like wrapping around the trunk of the host tree in an embrace which actually strangles in the end. And what remains is like a hollow trunk.” The host tree becomes a scaffolding that supports the epiphyte in producing a root system that can ultimately sustain life independently, and the guest tree appears against its host like decoration or musculature, before turning into an indiscernible whole and then the thing itself. The epiphyte eventually stands on its own with a clear, independent structure and purpose in a way that the prefix and the adjective never could. At some point in its life cycle, UPS and its offshoots might very well become indistinguishable from BAK’s institutional model and its privileging of speculative and theoretical approaches.

While the concept of the epiphyte and its transformation of established structures through acts of hollowing is visually and conceptually arresting, it still relies—at least in its introduction—on a kind of didacticism. Within an art and education context, the epiphyte is a term and a theory that must be taught before the transformational act of ultrasectionality can occur. UPS critiques the supremacy of dominant language forms, yet it employs theoretical English terminology or art-institutional discourse in its own framing. It’s possible for a participant to engage in UPS programming without knowledge or understanding of its epiphytic form, but without it and without the somewhat unwieldy “re-” and “ultra-” prefixes, there’s little to differentiate UPS from BAK’s other programming. Active, collective, and cooperative engagement therefore first demands theoretical engagement with language. While questions are raised, a language of elucidation (translation by way of explanation) pervades the trainings and the conceptual thinking behind UPS, belying the program’s invocation of a “fractal geometry … capable of representing life and lived experience.” This desire to remake the world or respond to states of emergency (political, environmental, cultural) might indeed happen through radical acts of collectivity, but it also seems to depend on relaying instructions and tactics for conceptual thinking.

Returning to Natalie Diaz, the poet has noted how closely translation is tied to proving or showing knowledge as a currency, and that misunderstanding or not understanding is a natural state akin to love: “I do think love is a not-knowing. I think that it is the willingness, the ability, or the luck of being in the space between what we know of one another and again very valuably what we don’t know about one another and yet can still be alongside.” 12 One collaborative work presented in UPS that exemplified this exploration of the space in-between the knowable and the unknown is Jason Dy’s Repose. Hanging in a cluster at the front of the exhibition space, the work is something between a collection of vestments, a tapestry, and a set of documentary images. Dy worked together with a cooperative of women embroiderers in Quezon City, the Philippines, to produce hand-stitched replicas of the artist’s ikebana arrangements. The bright but delicate compositions seem to levitate just off the fabric. Some arrangements show the stems of flowers that are visible through a translucent vase, and others are partly buried in earth or a ceramic vessel. Each features Jason and his co-embroiders’ names in thick black, curving around the image and meeting like friends in an embrace. Throughout the space, and in a walk led by Dy to sites of healing and death in Utrecht, the ikebana compositions came alive, adorning tables in the UPS gymnasium, exploding into a topological altarpiece with wood and dried flowers strung from the ceiling of the entrance hall, or laying at a gravesite. Instead of a translation from one form into another, the plant or flower arrangements suggest a transformational being hovering between life and death, perfection and imperfection. Similarly, UPS, as an ultracurricular epiphyte, conjures a paradoxical maneuver that must replace what was already there without erasing it. Ideally then, the school is always in mid-transformation—to identify an epiphyte clearly one must see its growth at work—which creates a sometimes necessary, sometimes unnecessary confusion. UPS has thrived in this environment, where unfolding contradictions and complexities provide evidence of progress.

Natalie Diaz, Postcolonial Love Poem (London: Faber & Faber, 2020), 49–56.

Natalie Diaz, “Postcolonial Love Poem: Part 1,” interview by David Naimon, October 23, 2020, in Between the Covers, podcast →.

Antena Aire, An Ultratranslation Manifesto (self-pub., 2013), 1.

Quotes about the program come from the booklet accompanying “Ultradependent Public School” and a conversation I had with Clara Balaguer and Jeanne van Heeswijk at BAK on April 20, 2023.

Anne Carson, “Variations on the Right to Remain Silent,” Float (New York: Knopf), 2016.

See →.

bell hooks’s teaching trilogy, and particularly Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope (2002), explores teaching as a profession of care and service, one that addresses and challenges forms of oppression and the politics of domination inside and outside the classroom.

Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red: A Novel in Verse (New York: Knopf, 1993), 10.

Carson, Autobiography of Red.

“D.A.F.O.N.T” stands for “Desiring Appreciation for Fonts Overlooked, Otherness Needs a Nice Natural Nuance Typeface.” For monstering, see Ece Canli, “Master’s Tools, Monster’s Tools,” in Glossary of Undisciplined Design, ed. Anja Kaiser and Rebecca Stephany (Leipzig: Spector Books, 2020).

Clara Balaguer’s 2016 essay “Tropico Vernacular,” published by Triple Canopy, has become a valuable reference in design education classrooms for its focus on vernacular design practice in the Philippines and the way a local visual language has developed from the tools available and the necessity of quick, effective forms of communication. See Clara Balaguer, “Tropico Vernacular,” Triple Canopy, May 3, 2016 →.

Diaz, “Postcolonial Love Poem: Part 1,” Between the Covers.