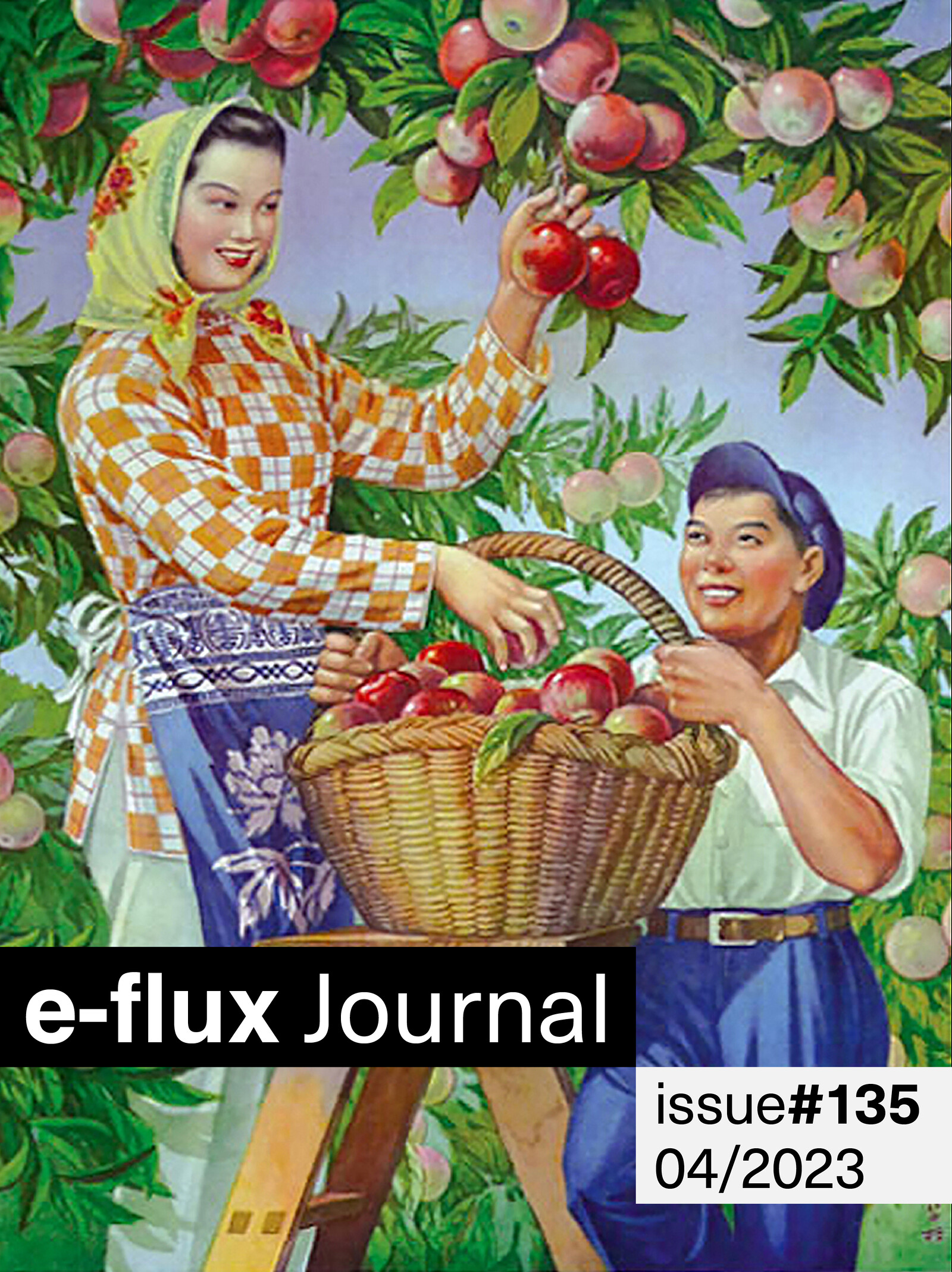

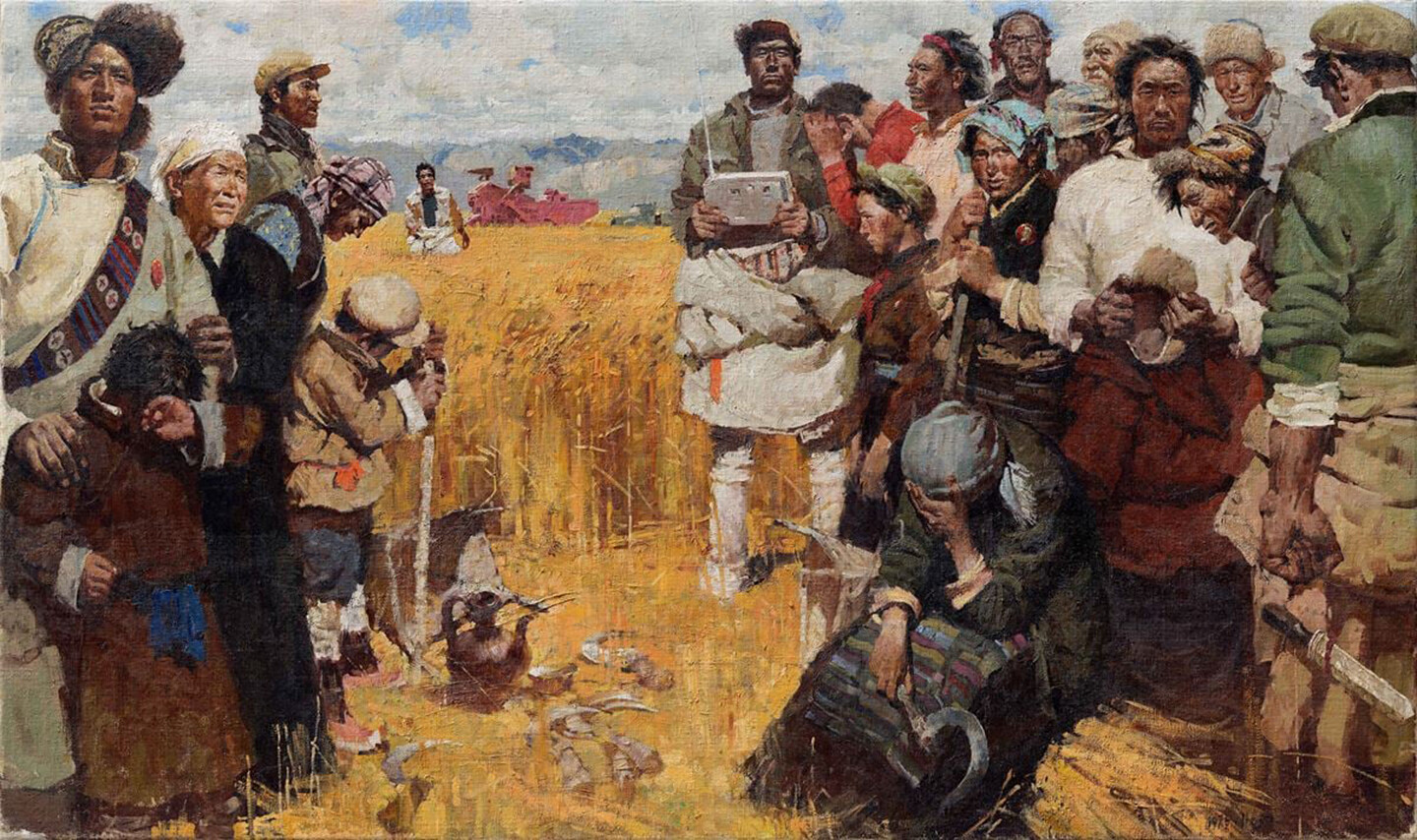

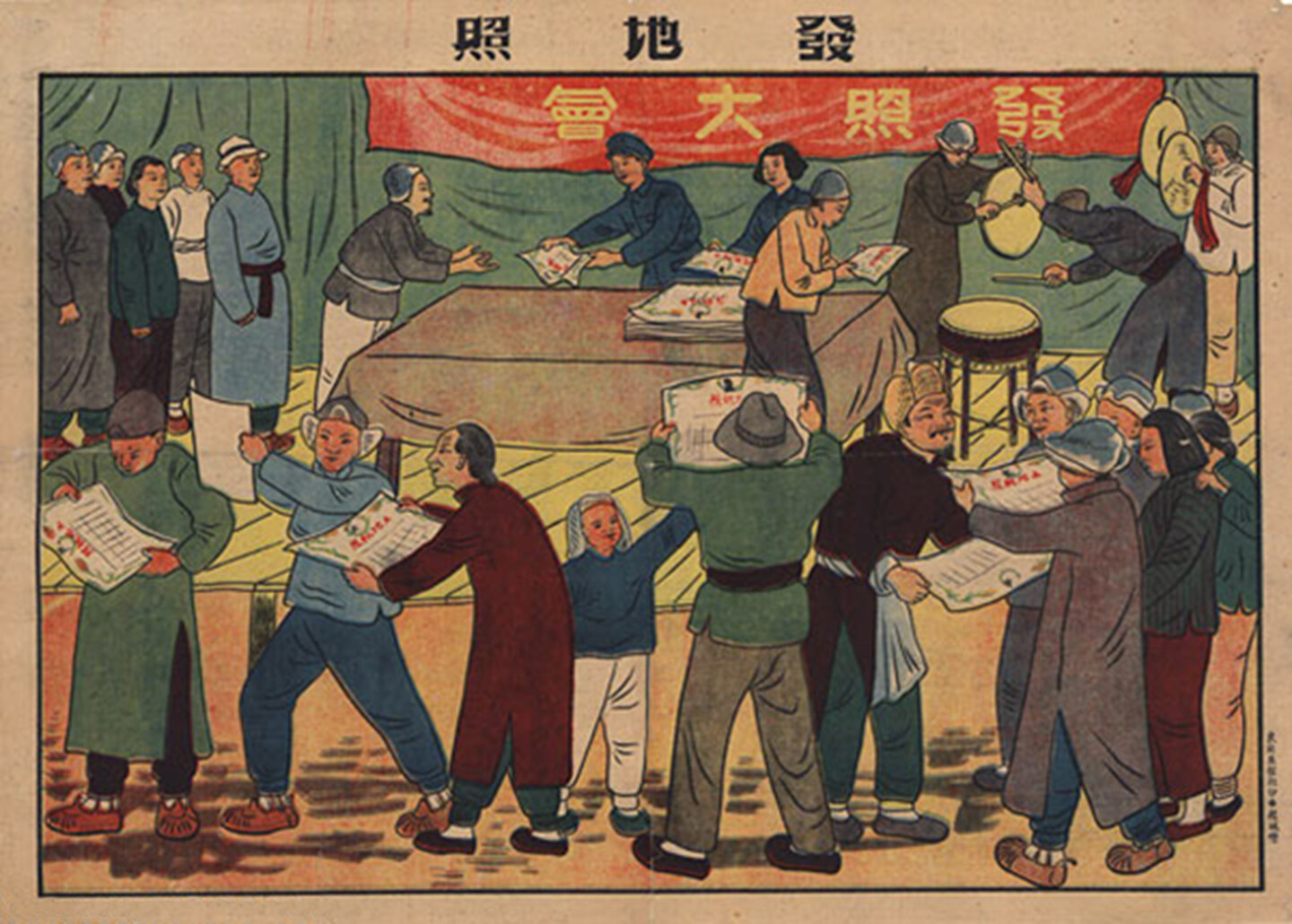

Art history has failed to competently account for the “post-socialist” in postmodernism, not so much as an interpretative framework but as a preexisting and indeed “haunting” condition. The hauntological dimension of post-socialist legacies might just be the missing link that allows us to understand much of postmodern art truly on its own terms, taking account of the inherent contradictions, mediations, and transformations of historical circumstances.

Some controversy emerges from amid the internality/transcendence dialectic. Precisely due to this unconscious realm, both artist and framework have the space to extend their own internality, activate their own vitality, and even deny their own staleness (陈腐) in order to open an orientation toward the future.

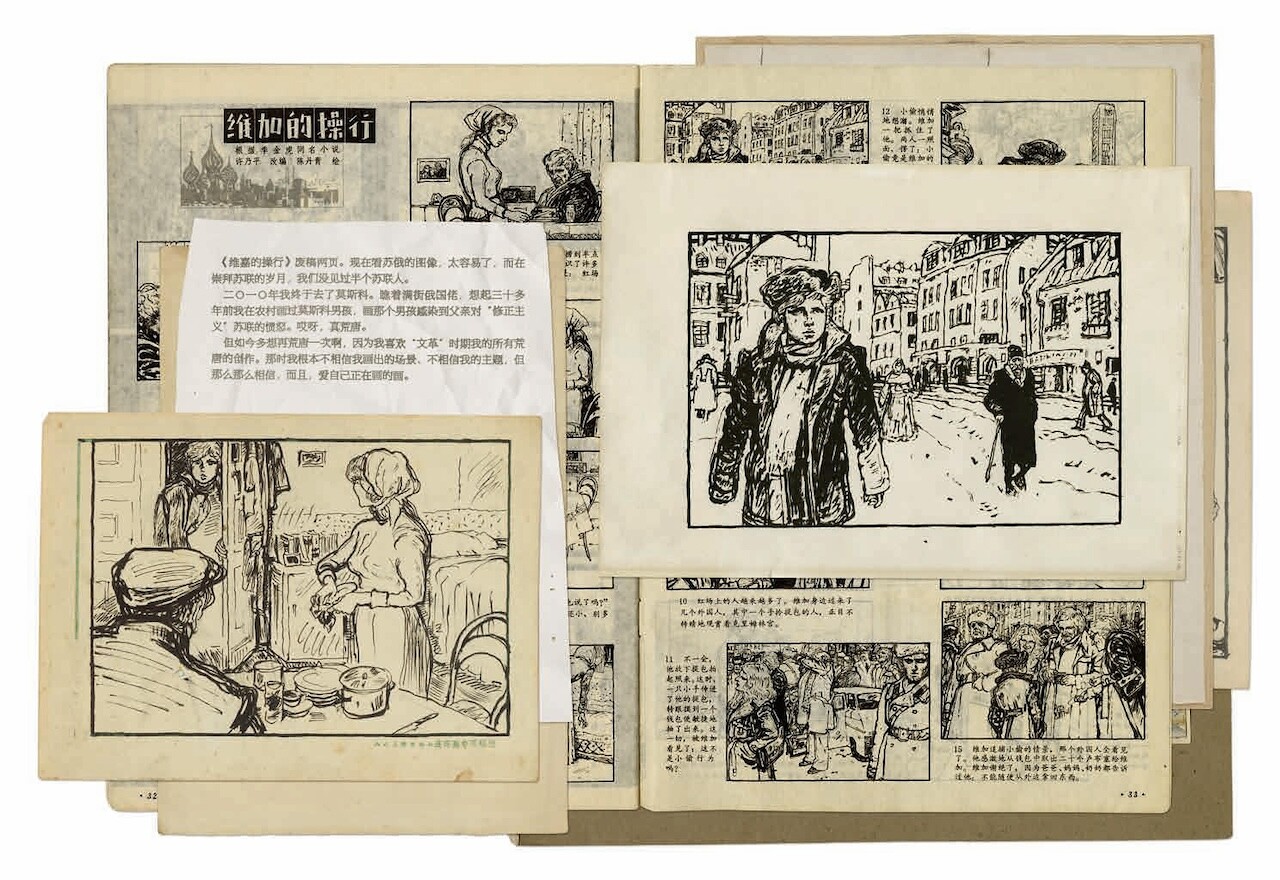

Although recognition of the artist as a creative individual is important, refusing to investigate the multidimensional nature of relationships and cultural interactions between the system and the people is tantamount to failing to attend to the pulse of history. Such practices can only result in an alienated past becoming an imaginative resource decoupled from history and present alike.

The project of a state based on collective property, thus overcoming the conflict between rich and poor, was formulated and thoroughly substantiated by Plato. Since his time, it has been repeatedly implemented, albeit on a limited scale, primarily in Catholic and Orthodox monasteries, but also in later religious and secular communities. However, the project was realized on the scale of an entire country for the first time by Lenin and his party. Although many regard their implementation of the project as unsuccessful, this view is historically naive. The first experiments of this kind are always short lived. After the French Revolution, democracy survived only a few years, and nearly everyone assumed that it would never be revived. The Soviet regime lasted much longer, and there is no doubt that there will be new attempts to create a classless society based on collective property. Ideas that have a thousand-year history do not vanish without a trace.

Revealing the hidden desire for capitalism in contemporaneous anticapitalist discourse and theory.

And to extend our analysis one step further: not only does Ninotchka provide a comic dissection of Soviet communism, it also contains a utopian horizon. This relates to the film’s double transformation, or double conversion, of the West to Marxism, and of communism to laughter, superfluity, and excess. Is not the real romance of film the romance between communism and surplus enjoyment? This screwball communism is what the (smiling) “Leninist” couple of Leon (the decadent Western reader of Marx) and Ninotchka (the laughing revolutionary militant) represents. “Luxury communism” is a facile phrase, but the more interesting question might be stated as follows: What would it mean to organize a society where surplus enjoyment would neither be ascetically denied nor captured by, and exploited for the production of, capitalist surplus value?

Book launch: Socialist Architecture: The Reappearing Act, Srdjan Jovanovic Weiss in discussion with Nina Rappaport

Young artists, novel and appealing, are quickly drawn into the art system. Frequently they enjoy an extended honeymoon period of being viewed, supported, consumed, discussed, and described. Meanwhile, artists who have been working since the 1970s and ‘80s are highlighted as part of a particular art movement, even being lauded as the movements’ leading or representative figures, gaining the affirmation of the art system. These older artists have been brought into international exhibitions that focus on presenting Chinese art, and have been the center of attention for collectors and the art market. However, after so many years, their work remains undescribed in terms of its art-historical relevance.