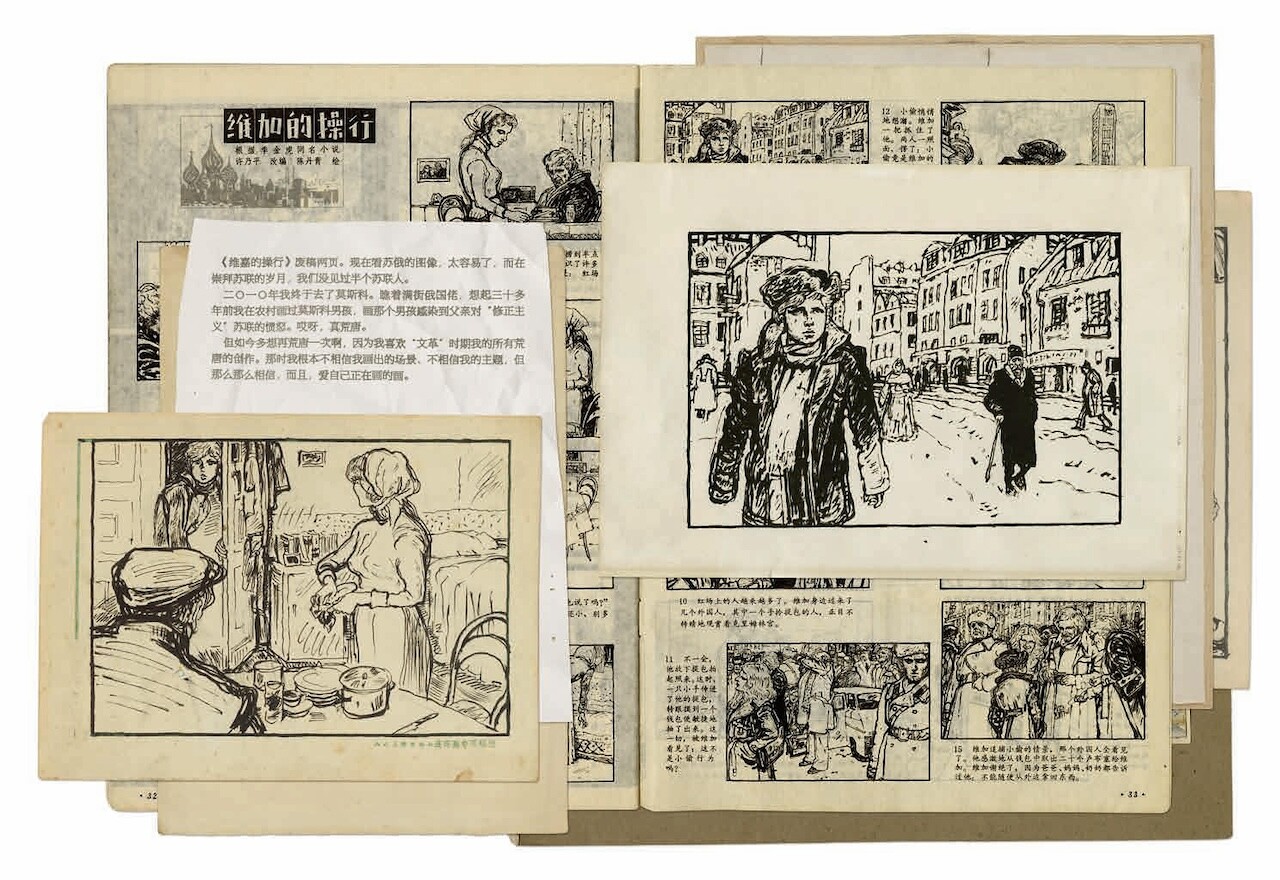

Chen Danqing, sketches for Vitya’s Conduct, in Goodbye Sketches (Phoenix Art Publishing, 2022), unpaginated.

P.S. To my dismay I learned years after this [essay] saw print that Repin never painted a battle scene; he wasn’t that kind of painter. I had attributed someone else’s picture to him. That showed my provincialism with regard to Russian art in the nineteenth century.

—Clement Greenberg, 1972 postscript to his 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”

Shortly after ChatGPT launched in late 2022, Chinese netizens began experimenting with the powerful AI tool to generate application letters to join the Communist Party—a highly standardized genre of writing that usually chronicles the applicant’s bildungsroman discovery of, and eventual allegiance to, the party’s utopic political vision. This narrative structure is also prevalent in socialist-realist literature and theater, including iconic revolutionary ballets like The Red Detachment of Women. So standardized is this writing that it’s virtually timeless: W. E. B. Dubois’s 1961 letter to join the CPUSA could have easily been written in 2024.1 Cultural theorist Mikhail Epstein practically anticipated this use of AI by observing that the “Soviet Marxist ideological language is by its very nature artificial” and that “with specific formulas of functions and markers, [a] computer would be capable of composing Soviet ideological texts.”2 Web culture’s intuitive understanding of this principle illuminates an overlooked yet infinitely productive perspective on socialist realism: that of the “user,” trained en masse on a set of aesthetic and ideological data, indoctrinated in more ways than one can consciously account for.

It appears that current discourse (and feelings) around socialist realism revolve, roughly, around two poles. One is archive-intensive research that hopes for an explosive, groundbreaking exposé from never-before-seen documents, though this is unlikely to shake the inertia of accumulated impressions and biases; that is to say, it is unlikely to change people’s minds. More importantly, it is often the peculiarly inaccessible archives (such as those of the original production of The Red Detachment of Women) that signal what remains sore, operative, potent. The other pole concerns taste and “aesthetic judgment,” which has become decidedly awkward given the cultural pluralism, identity politeness, and respect for the “other” that is now demanded, at least at surface level, even for a post-Socialist other. From the user’s perspective, however, aesthetic discernment is beside the point; what’s at stake, rather, is the indiscernible thick of things that trickles, persists, and haunts, like some feral organism. The avant-garde’s desired outcome of blurring the boundaries between life and art has all but become a mundane—and often brutal—reality.

The user reenacts the Soviet film Lenin in 1918 (1939) and Swan Lake choreography as Freudian episodes in the Chinese film In the Heat of the Sun (1994), or creates #dreamcore images of dilapidated factories and worker’s palaces, or socialist-brutalist residential complexes that are interchangeable between Beijing and Zagreb. The user reshares propaganda posters about international and cross-racial solidarities that are unmistakably queer, or complains, in the case of a friend of mine who is a professor of oil painting in Guangzhou, about her futile attempts to cleanse her students of the “soy sauce” tonality—a remnant of Soviet-era pedagogy that still dictates the grind of art school exams in 2024. The user furnishes homo-erotic fan-fictions for TV shows about underground Communists in Shanghai during the Sino-Japan War with details about the Frunze Military Academy.3 The user may be a head of state rekindling the old Sino-Soviet romance for strategic geopoliticking. A bigger—and more interesting—challenge than prying open sealed state archives is beginning to make sense of the abundant, erratic evidence of lived experience.

Film still from Jean-Luc Godard, La Chinoise (1967).

We might benefit from taking fan fiction and cosplay a bit more seriously. The artist and public intellectual Chen Danqing, a student of the students of Konstantin Maksimov (the Soviet oil-painting pedagogue sent to China in the 1950s), recalled channeling the rambunctious group portrayed in Ilya Repin’s Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880) while sketching a group of Chinese peasants playing a card game in 1975. He regarded trips to sketch and paint in Tibet as opportunities to make Soviet paintings. During these village years, he created a socialist comic about a young Moscow boy outraged by the revisionist tendencies of contemporary Soviet society. Looking back on this picture book, he confessed that “during the years of idolizing the Soviet Union, we did not even see half of a Soviet person.” How fundamentally different, truly, is Chen’s imagined Moscow boy from the Maoist French students in Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise? Chen, of course, fully understood the absurdities of his ideological fan fiction of Soviet political life; “however,” he continued, “how I wish to be absurd once more. I actually like all of my absurd works during the Cultural Revolution. I did not believe in the scenes or subjects I had painted at all, but I so very much believed in—and loved—the paintings I was making.”4

And we’re still supposed to be talking about taste and aesthetics?