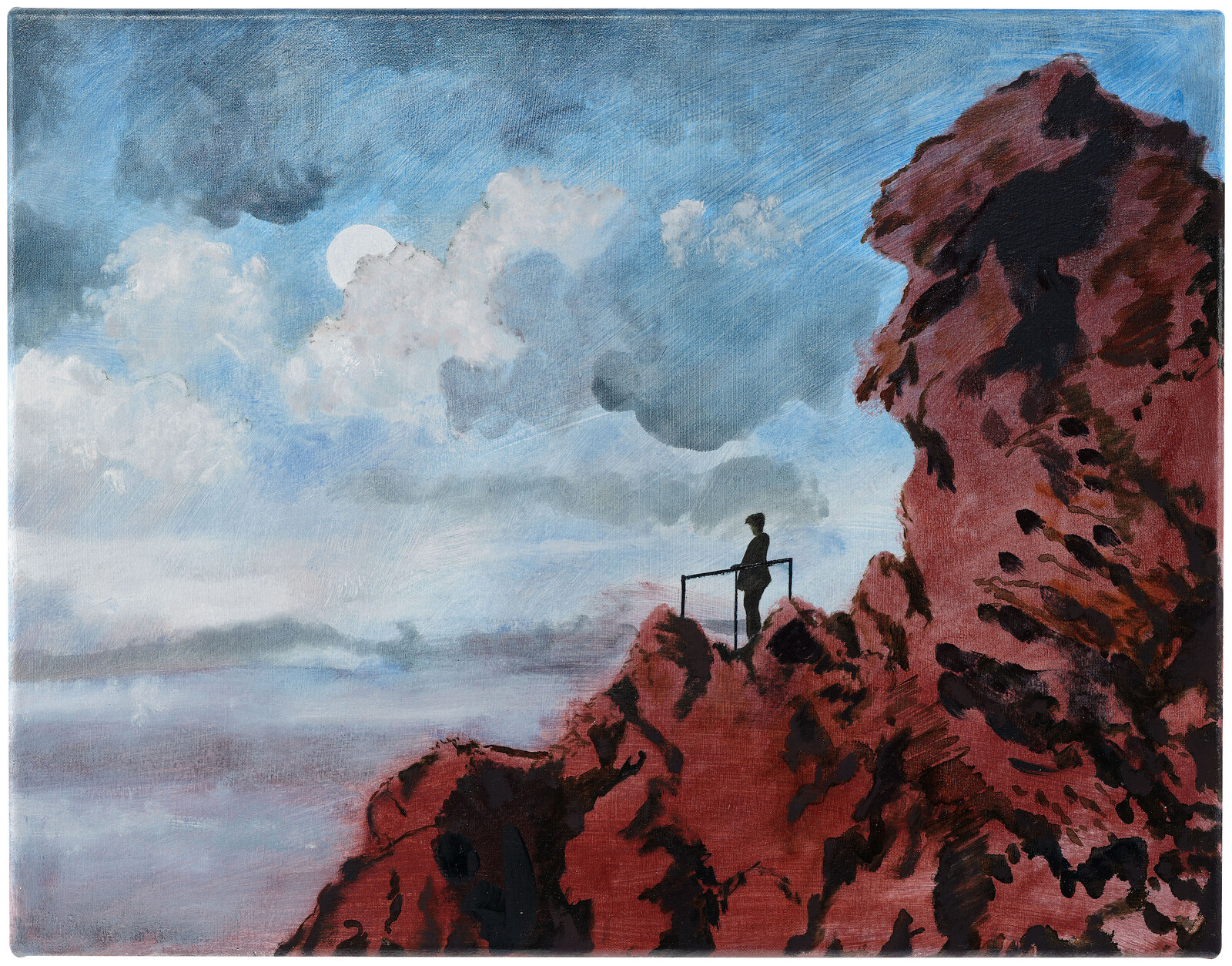

In past centuries, almost every philosopher was addressed according to nationality, and a new school of thought was often prefixed with a nationality. A thinker can only go beyond the nation-state by becoming heimatlos, that is to say, by looking at the world from the standpoint of not being at home. This doesn’t mean that one must refrain from talking or thinking about a particular place or a culture; on the contrary, one must confront it and access it from the perspective of a planetary future.

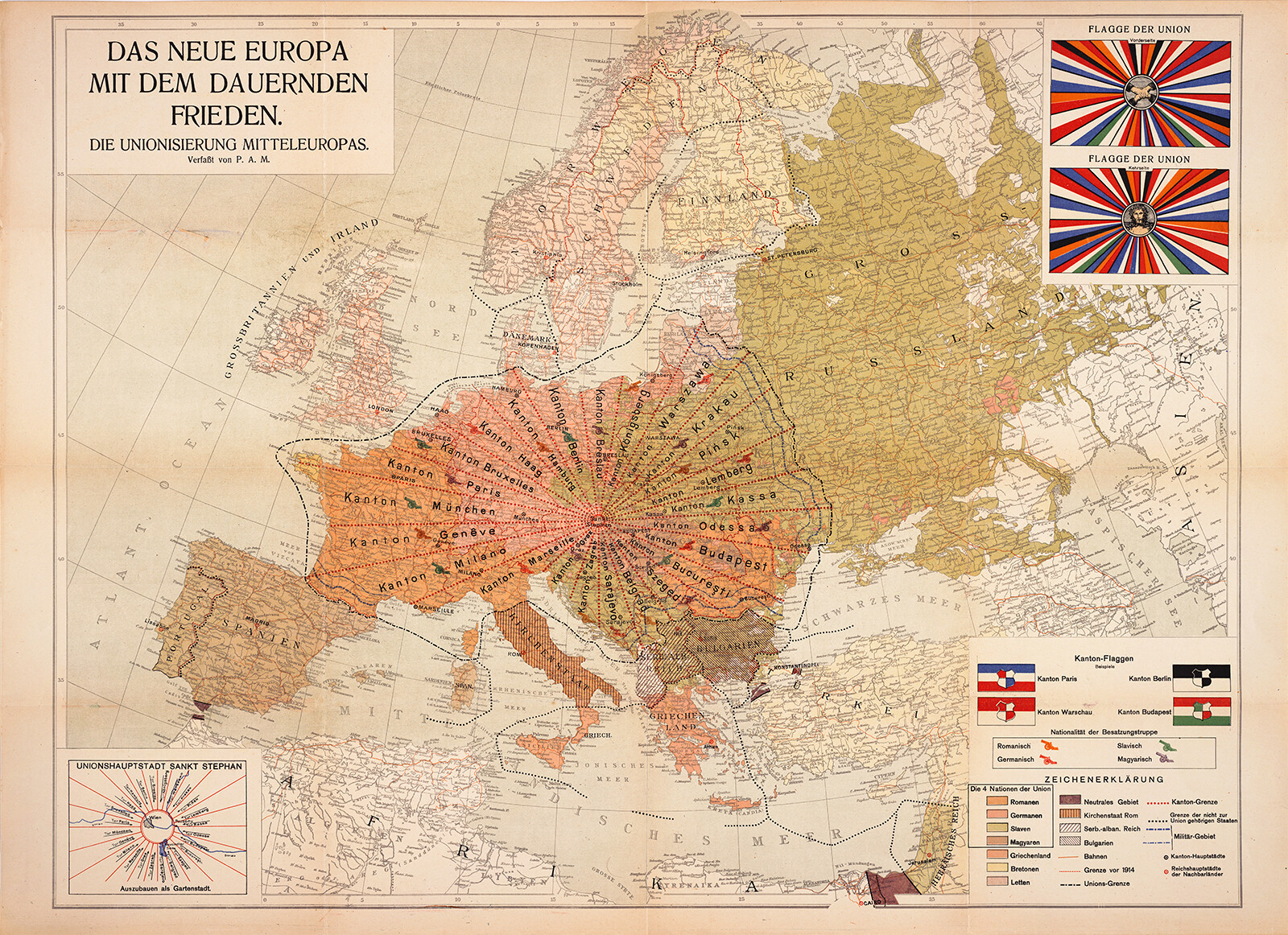

In the twenty-first century, we can easily sense that this process of destruction and recreation is only accelerating rather than slowing down. The longing for Heimat will only be intensified instead of being diminished; the dilemma of homecoming can only become more pathological. In fact, two opposed movements are taking place at the same time: planetarization and homecoming. Capital and techno-science, with their assumed universality, have a tendency toward escalation and self-propagation, while the specificity of territory and customs have a tendency to resist what is foreign.

Basim Magdy: Flickers of Utopia

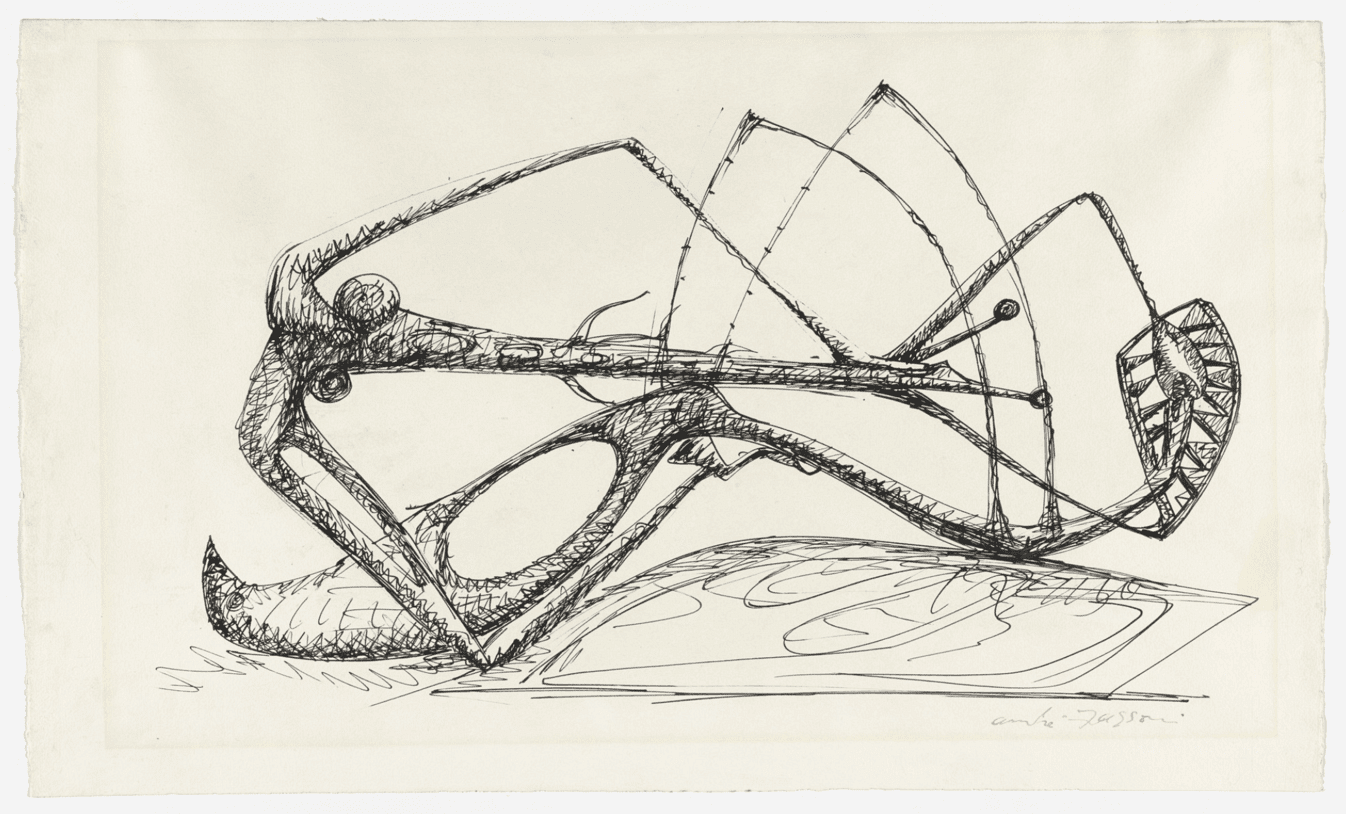

We are conditioned, even neurologically impaired, by what modernity does to us. But we are not determined by it; we can find other ways to rewire ourselves. This rewiring is a collective process; there’s no way an individual can do it alone.

This text might be framed as an offering, an attempt at releasing latent animist lines of possibility for what late twentieth-century works like Bronze Head might do for us in our current climate of rising anti-queer sentiment, on the African continent and elsewhere.

It is only possible to speak of independence, beyond a political or economic gesture, when it is revealed that the only common experience is the denial of experience—the end of experience, where one can no longer navigate, where separation and mystery are retained, and a sovereignty of each self is assured even if only as an instant, a space, or a way of life.

Brazilian authority becomes trapped in producing potlatch after potlatch, transforming its legitimacy into a promise while constantly governing in the name of the exception, in the hope of consumption and expenditure, of enjoying a sacrifice so extraordinary as to erase its spurious and deficient character. It is this debt that allows the colonizer to coexist with the settler insofar as the colonizer can continue to explore, consume, and enjoy through the potlatch, and the settler can see in the colonizer’s enjoyment and expenditure the future birth of law and name. And yet, this birth is always postponed because the authority is burned, inevitably consuming itself in the fire of expenditure, from which the farce of hope and name must be restored with new clothes.

New York launch of e-flux Journal issue 133, with Serubiri Moses, Kateryna Iakovlenko, and Thotti

There is a light hovering over the end of the world, only visible at the very edge of the world. A torturous cross rather than fire or flame, this light hurts more in its distance than its encounter—already impossible without a name for summoning it. This light is conjured within the blindness of the night’s currents, a night that dresses the castaways of Iberian galleons as stars. This light is not a guide, though at the end of the world, it was prone to misuse, whether as astrolabe or compass.