Why do you teach?

I transitioned from a full-time curatorial position to the MA Art Education, Curatorial Studies only a few months ago, but I had always taught on the side, if only for a few days a month, out of a passion for the kind of conversations that are unique to the academy and a curiosity about changing frames of perception. For more than ten years, I headed the exhibitions department at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. There my many collaborators and I developed exhibitions that were themselves forms of research in the sense that they developed historiographic models and methods to overcome the false oppositions—such as art and politics—that dominate discourse. These include exhibitions such as “Animism”; “Forensis,” the first Forensic Architecture exhibition; “Parapolitics”; and, more recently, the Sylvia Wynter-inspired exhibition “Ceremony.” It became time for me to begin to translate these experiences into a curriculum, a toolbox. The young discipline of curatorial studies finds itself, just like museums at large, under massive pressure, as all previous certainties are questioned, from historical narratives and framings to basic assumptions on which the entire modern system of knowledge and disciplinary divisions rest.

What conversations develop in the academy but perhaps not in the museum?

I have a lot of trust in the younger generations, with whom we generally don’t have to have a lot of unnecessary conversations about the state of affairs concerning mechanisms of social exclusion, the violence that is reproduced by monocultures, and the state of the planet.

Institutions like museums are inevitably oriented at and concerned with systems of classification, categorization, and status distribution; that is, after all, the essence of institutions and what the discourses that uphold them serve to reproduce. And these systems are in a very real sense supra-individual. I’m not normally a fan of quoting Walter Benjamin, but, in the academy, there is more space to discuss and reflect on what he called “the most terrible drug—ourselves.” 1 Given the economic and systemic paradigm under which we are living, there is, in art academies, a lot of discussion about the place of the artist and artistic institutions in society. These discussions are especially concerned with the artist-figure as the embodied paradigm and mediation of capitalism and its (failing) promises: if you work hard or sell yourself successfully as a brand, you can make it, but if you don’t, then it’s your own fault. But in the everyday life of the academy, everybody is always in crisis, and that provides the ability to see the dominant forms of subjectivity as being in permanent crisis. Now, what do we make of that? There is such an unbearable gulf between the urge for fundamental transformation in the face of the global catastrophe and the mechanisms of reproduction of the status quo. In the academy, instead of being crushed by it, we can take measure of that gulf. And in doing so, we can develop commitments and also figure out what role we intend to play in the lives of others. Ultimately, that is where an ethics develops that should inform institutional practice.

With your experience as a point of departure, how did you begin assembling an academic curriculum?

My predecessors have built a well-crafted master-level curriculum that not only focuses on contemporary art curation but also concerns curation in an expanded field and prominently includes art mediation. In the near future, we will also have a joint PhD program in cultural analysis.

We are experiencing now a real paradigm shift in the role that art and its institutions play: the real world breaks into the ivory tower of art in ways that meaningfully place the very definitions and structures of knowledge into question. It is simply no longer sufficient to learn about contemporary art and how to curate good exhibitions. We have to broaden the horizon if we are to deal with the historical baggage that exhibitions carry, which isn’t really “historical” but breaks open and washes ashore in the present and cannot be kept at a safe distance. Linear history, in that sense, is all but dead.

To be frank, I don’t think that what the world needs right now is many more programs that educate contemporary art curators in the narrow sense of “curating.” Museums won’t be able to change with the current toolbox alone. In a way, the era of the curator seems to be over, to me, at least in terms of the paradigms that have emerged since the 1970s and perhaps have also come to a sort of symbolic end for good with the last documenta.

Now, the challenges and responsibilities of curators are of a completely different register: questions of power differentials and social exclusion turn museums into symbolically embattled zones, and we can no longer look at art in isolation, not least because these questions are at the core of artistic production, too, and artists themselves face different calls for accountability. The temporary prominence of the curator-figure was already a result of that post-autonomous encroaching of “context” into the field of art, which seemed to produce a demand for a mediating agency, but I think the developments of the last two decades—by which I mean the effects of digital capitalism on cultural production and geopolitics at large, along with the demise of (neo)liberalism and changes within the global elites and their investment in the arts—really force us to recognize that curatorial discourse as we have it right now is not living up to the tasks ahead. Now especially, in the context of escalating culture wars, it has become increasingly impossible to secure institutional legitimization in the disciplinary mold that we have inherited, such as through the authority of art history, for instance. Everything calls for context and recontextualization—now on a different scale—by being accountable for the constitutive exclusions that historically formed the disciplinary fields and value forms of a Euro-American dominated modernity. The entire symbolic field of history, and its framing, is at stake.

It is a necessity and a great opportunity for curatorial studies to reinvent itself as a research-based practice whose domain is, in the broadest sense, the question of framing the image and narrative of history. Mark Wigley proposed that curating and research were inherently inseparable and suggested that this history may reach back at least to the Library of Alexandria. But in the historical disciplines, not even the imagined civilizational threshold that is the invention of writing can be upheld: it is a myth that has made the larger part of human history and culture illegible. This is the case wherever we look: there are incredible paradigm shifts in the historical disciplines that concern the scaffold of all our narratives about who we are, both as a species and as so-called moderns. However, if these revisions of the scaffold are entering the museum at all, it is often only in terms of representational rights and identities. I am not in some general sense opposed to that at all, but I do think that the admittedly catastrophic prospects of the present make it necessary to rethink the institutions that have largely determined our relation to history and museums in infrastructural terms and on a global scale. Such rethinking must go beyond the confines of identity to create a common basis for planetary action and solidarity in a time when the entire range of modes of othering and tools of divide-and-rule that have existed in the history of the human species are being washed up by death-drive capitalism and its undead modern forms: the nation state, the binary gender system, and the idea of what constitutes a “civilized” subject.

“Art” is more of a problem in this respect than a solution, because in art we tend to adhere to terrible superstitions of historical and even evolutionary development. The idea that “history is written by the winners” is a heroic, patriarchal fantasy that is enactable only by violence, and it has been broadly challenged in the present. When asked about decolonizing the field of archeology, David Wengrow answered that before anything else, it is a demand that today emerges from the findings of the field itself. What follows from that line of thought is that a decolonial science is not only possible but emerges as an immanent demand. The alternative is pseudoscience and collective lies, which are both inherent to fascism. This demand is what a future curriculum in curatorial studies has to reflect.

How do you perceive this pressure has changed curatorial studies? And how do you distinguish curatorial studies, a “young discipline,” from art history or art theory?

The epistemes of the present are on the move, and they are doing so in the context of an undead modernity and undead modernism. We need to realize the degree to which our conversations are limited by the disciplinary enclosures we inhabit. These enclosures make the larger part of life and the world literally illegible, because they impose epistemic foreclosures and forms of amnesia that concern the history of the human species at large. The current landscape of disciplines mirrors the division of labor in the context of imperial and national geographies, and reproduces their falsely naturalized myths. For museum collections, for instance, it is simply not enough to enlarge the frame while keeping the basic categories in place; this is what happens when we simply add previously excluded things and practices to the canon of art, as demonstrated in the rehang of the Museum of Modern Art, to name but one prominent example. Art history is an amazing discipline that has much to teach, but it also is a prison, and a border regime that separates “art“ from the symbolic and communal activity by which people generally live and survive. What Gerald Vizenor termed the “survivance“ of Indigenous people, or the history of Afro-diasporic culture, or a feminist rewrite of civilizational history, for instance, cannot be done justice in the categories of art history or theory without changing the very definition of those fields. This is the paradox and irony of the present: curatorial work is about the need to reframe what is at stake in terms other than what this system of divisions and value production can provide. I think of this as a liberatory moment.

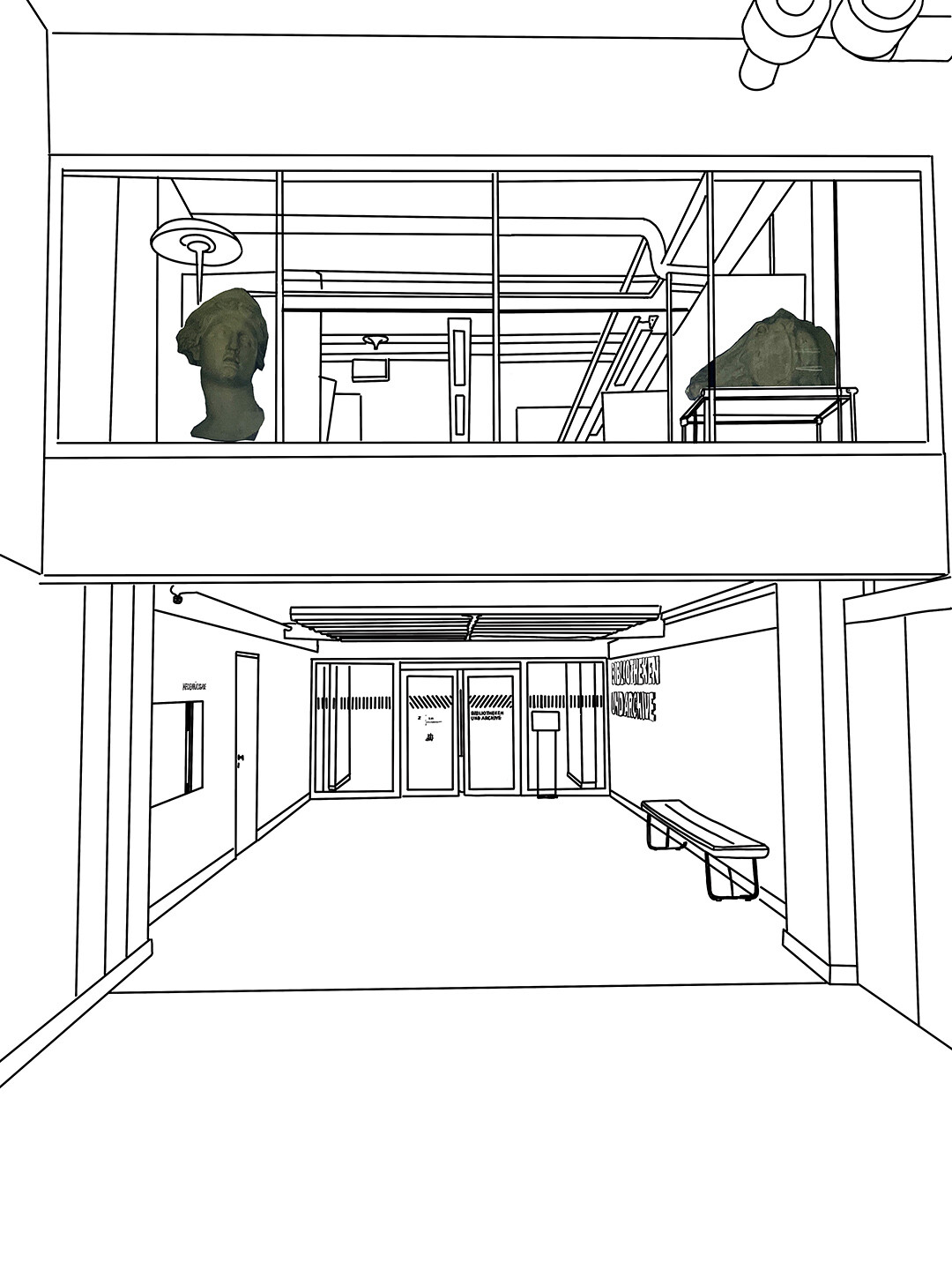

Vivianne Tat, sketch for The Person in Question, an exhibition by students of the Master of Art Education Curatorial Studies, Zurich University of the Arts Library, Zurich, May 31–June 26, 2023.

How do you measure the distance between the urge for transformation and the perpetuation of the status quo? And how do students develop commitments and determine what roles they want to play in the lives of others?

This brings up that Lauryn Hill line, “I find it hard to say that everything is alright.” This feeling acts as a driving force in the quest for both change and knowledge. I think of it in terms of interlocking cycles of crisis that need a facilitating environment, where we can sound out and differentiate its individual, existential, and systemic dimensions. Crisis occupies two ends of a spectrum: nothing is alright, everything is alright. Knowledge and being affectible throws us into crisis. So, we, the students and I, might spend the entire day in a collective learning space that is all consciousness-raising about systemic parameters, like the gap between aspirational discourse of contemporary art as a somewhat democratizing force and the realities of its links with the fossil fuel industry, for instance. And we are like, and should be like, “The place is burning, nothing is alright.” To put up a critical photograph of the fires around us isn’t going to make a change. Quite the opposite: it perpetuates the status quo. This consciousness-raising might become a commitment and inform a curatorial practice. At the same time, both within the group and when we go home at night, we might make others and ourselves feel like everything is all alright.

How we deal with individual crises and socialize them is really the essence of it, and it is crucial also in terms of becoming affectible. We have to allow things around us to decenter our sense of self, and this is what enables us to develop a literacy in the first place, especially of all that might at first appear too quotidian or even unfamiliar and outright illegible. The flow of images in our social media feeds might conceal most of what happens in this world, what remains almost completely invisible and illegible to most of us. So, considering the role that culture plays, we need to actively work against becoming promoters of monoculture. And this can begin with straightforward questions about art: When did you last feel a work of art change you? When did you last contemplate a work that was initially totally illegible to you?

By “taking measure” I mean becoming conscious of the gulf between transformation and stasis, which is really about understanding desire and developing a literacy for how desire is systemically conditioned and anti-systemic at the same time. “Taking measure” is a term for being able to address things in a collective way. This prevents us from taking things personally and internalizing them, as if it were the individual that was the problem. Whenever we allow for this personalization to occur, we become mediators of the gap, the glue that glosses over the material realities of unfreedom in which we all live and the templates of subjectivity that are on offer to demonstrate the aspirational “freedom” offered by capitalism. This is, of course, what art and culture are tasked with and how their systemic usefulness is evaluated and measured.

With museums so embattled, must these commitments remain within institutions? Where else might they operate?

Not at all, they must not stay in institutions. They operate wherever they take you, that’s just what commitments do. They are the opposite of abstractions.

What references, precedents, or models do you call upon to communicate these ideas in your teaching?

In “The Postcolonial Constellation,” Okwui Enwezor makes two important points: that modern art history has been bound to the history of its exhibitions and that the history of exhibitions takes place within the frame of a history of thought. 2 But the history of thought cannot be contained by the disciplinary enclosures we have inherited as undead forms. So, we take up examples from history but must ask ourselves, where have these enclosures placed limits on what was initially a progressive agenda? It is not sufficient to add what was formerly excluded into given categories, because this stabilizes the very categories that uphold the enclosures, such as modernism, that need to be reworked.

How can one break out of the prison of disciplinary enclosures?

I think curatorial studies really has the potential to become a field about exactly this rethinking, which is above all a historiographic task, one with enormous consequences for our political imaginaries and senses of possibility in the present. What the field is dealing with now are how images and narratives, in the broadest sense, condition ways of seeing and ways of understanding. These are questions about framing: framing displays, framing narratives (of art history, of culture, of civilizations, of crisis, etc.), framing concepts, and framing institutional or disciplinary systems of categorization and classification. A research argument in the context of curatorial studies typically reframes how something is usually perceived or how questions are usually posed.

What I am talking about is not what we usually think of as inter- or transdisciplinary work. You can’t get out of disciplinary enclosures just by putting the disciplines “in dialogue” while leaving their foundational assumptions in place. You have to tackle discursive divisions and border regimes themselves and find a vantage point, through historical recourse, where these divisions, which are formative of how disciplines make their subject matter, are not a given. If you want to break out of the enclosure of art history, for example, you have to undermine the foundational assumptions of the field—which are written according to what it separates itself from, already and continuously—and these mechanisms of division and evaluation. This is the real challenge of decolonial historiography, and it sheds a different light on the question posed above, as well.

Breaking out of such a prison is not comparable to liberating oneself from captivity into freedom. The effects of colonialism and its border regimes, its discursive thresholds, and its sorting mechanisms, which are deeply ingrained in the modern division of labor in the academy, do not offer a total escape, a total liberation, because we are ourselves its products. All we can do is engage in the transformative work of recategorization. This is most powerfully described by Franz Kafka in his “Report to an Academy.” The protagonist of this parable on assimilation, who is caught on the brink of the animal/human threshold, realizes that there is no possibility of breaking out into absolute freedom, and hence the “way out” is to rework the categories and basic assumptions in the minds of others.

What do you envision for the future of curatorial education?

I think the future is closely related to a notorious problem in the political and, perhaps especially, the decolonial imaginary today: the challenge of disbanding the false dichotomies and sense of alternatives that structure much of the social imaginary in the present. Everyone who has thought about this question has inevitably come to realize that this is a key problem of all discourses of modernity in a broader sense, notably of structuralism and poststructuralism, that is, how the supposed alternatives are themselves the discursive products of modernity’s mechanisms of division. Think of the “invention of tradition,” or of the “romantic imaginary,” or of the way a non-secular, religious world is conceived: in each instance, the terms of the division that underlie modern discourse and its social contracts are fully accepted rather than unhinged. And this produces a terrible enclosure, which renders illegible much of how humans actually live and survive. Through the work of recategorization, curatorial studies is a field where culture can be made legible on terms that are not defined by these divisions or by the logic of negation. This marks a departure from the paradigm of critique, too, without simply slipping into the affirmative but making space for affirmation on other terms.

Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism,” in Selected Writings, Volume 2, 1927–1934, eds. Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, trans. Rodney Livingstone and others (Belknap, 1999), 216.

Okwui Enwezor, “The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition,” Research in African Literatures 34, no. 4 (2003): 57–82.