Nika Dubrovsky

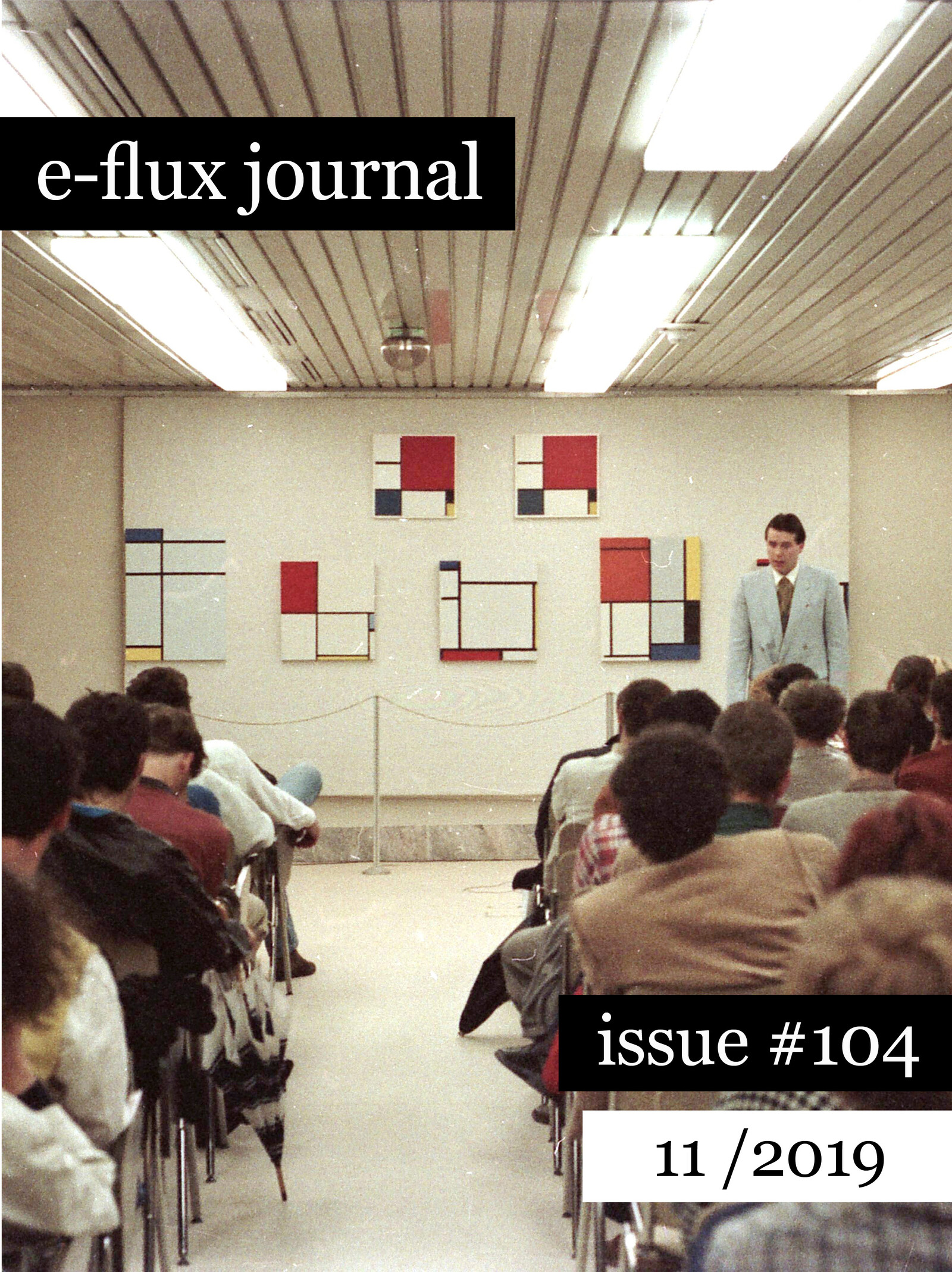

Many argue that we should stop the movement of hundreds of thousands of art tourists around the globe, stop building pointless new offices, stop hosting so many exclusive presentations and dinners that serve no purpose other than self-celebration, and imagine how art could be one of many forms of care that contributes to the reproduction of human life (education, medicine, safety, different forms of knowledge, etc.). How else could it be possible for everyone to cultivate local artistic communities as ends in themselves? These are sensible proposals, but they lack the coherence and urgency of the demands being made to defund or abolish the police. What would any of this actually mean in practice? As a thought experiment, if we were to storm the Louvre or Hermitage again, what would we do with it? Anything? It’s also possible that palaces simply don’t lend themselves to democratic purposes.

True, artists too less and less resemble industrial workers, and more and more resemble managers. But they are still heroic, highly individualized managers nonetheless—that is, the successful ones (the lesser figures are now relegated largely to the artistic equivalent of care work). And it’s telling that, whatever else may change, and however much the Romantic conception of the artist now seems to us trite, silly, and long-since-abandoned; however much discussion for that matter there is about artistic collectives; at a show like the Venice Biennale, or a museum of contemporary art, almost everything is still treated as if it springs from the brain of a specific named individual.

We would like to offer some initial thoughts on exactly how the art world can operate simultaneously as a dream of liberation, and a structure of exclusion; how its guiding principle is both that everyone should really be an artist, and that this is absolutely and irrevocably not the case. The art world is still founded on Romantic principles; these have never gone away; but the Romantic legacy contains two notions, one, a kind of democratic notion of genius as an essential aspect of any human being, even if it can only be realized in some collective way, and another, that those things that really matter are always the product of some individual heroic genius. The art world, essentially, dangles the ghost of one so as to ultimately, aggressively, insist on the other.

Editors

_02.jpg,1600)