It is a wonder we let fetuses inside us. Unlike almost all other animals, hundreds of thousands of humans die because of their pregnancies every year, making a mockery of UN millennium goals to stop the carnage. In the United States, almost one thousand people die while doing childbirth each year and another sixty-five “nearly die.” This situation is social, not simply “natural.” Things are like this for political and economic reasons: we made them this way.

Pregnancy undoubtedly has its pleasures; natality is unique. That is why, even as others suffer deeply from their coerced participation in pregnancy, many people excluded from the experience for whatever reason—be they cis, trans, or nonbinary—feel deeply bereft. But even so, and even in full recognition of the sense of the sublime that people experience in gestating, it is remarkable that there isn’t more consistent support for research into alleviating the problem of pregnancy.

The everyday “miracle” that transpires in pregnancy, the production of that number more than one and less than two, receives more idealizing lip-service than it does respect. Certainly, the creation of new proto-personhood in the uterus is a marvel artists have engaged for millennia (and psychoanalytic philosophers for almost a century). Most of us need no reminding that we are, each of us, the blinking, thinking, pulsating products of gestational work and its equally laborious aftermaths. Yet in 2017 a reader and thinker as compendious as Maggie Nelson can still state, semi-incredulously but with a strong case behind her, that philosophical writing about actually doing gestation constitutes an absence in culture.

What particularly fascinates me about the subject is pregnancy’s morbidity, the little-discussed ways that, biophysically speaking, gestating is an unconscionably destructive business. The basic mechanics, according to evolutionary biologist Suzanne Sadedin, have evolved in our species in a manner that can only be described as a ghastly fluke. Scientists have discovered—by experimentally putting placental cells in mouse carcasses—that the active cells of pregnancy “rampage” (unless aggressively contained) through every tissue they touch. Kathy Acker was not citing these studies when she remarked that having cancer was like having a baby, but she was unconsciously channelling its findings. The same goes for Elena Ferrante’s protagonist in The Days of Abandonment, who reports: “I was like a lump of food that my children chewed without stopping; a cud made of a living material that continually amalgamated and softened its living substance to allow two greedy bloodsuckers to nourish themselves.”1

The genes that are active in embryonic development are also implicated in cancer. And that is not the only reason why pregnancy among Homo sapiens—in Sadedin’s account—perpetrates a kind of biological “bloodbath.” It is the specific, functionally rare type of placenta we have to work with—the hemochorial placenta—which determines that the entity Chikako Takeshita calls “the motherfetus” tears itself apart inside.2 Rather than simply interfacing with the gestator’s biology through a limited filter, or contenting itself with freely proffered secretions, this placenta “digests” its way into its host’s arteries, securing full access to most tissues. Mammals whose placentae don’t “breach the walls of the womb” in this way can simply abort or reabsorb unwanted fetuses at any stage of pregnancy, Sadedin notes. For them, “life goes on almost as normal during pregnancy.”3 Conversely, a human cannot rip away a placenta in the event of a change of heart—or, say, a sudden drought or outbreak of war—without risk of lethal hemorrhage. Our embryo hugely enlarges and paralyzes the wider arterial system supplying it, while at the same time elevating (hormonally) the blood pressure and sugar supply. A 2018 study found that post-natal PTSD affects at least three to four percent of mothers in the UK (the US percentage is likely to be far higher—especially among black women).4

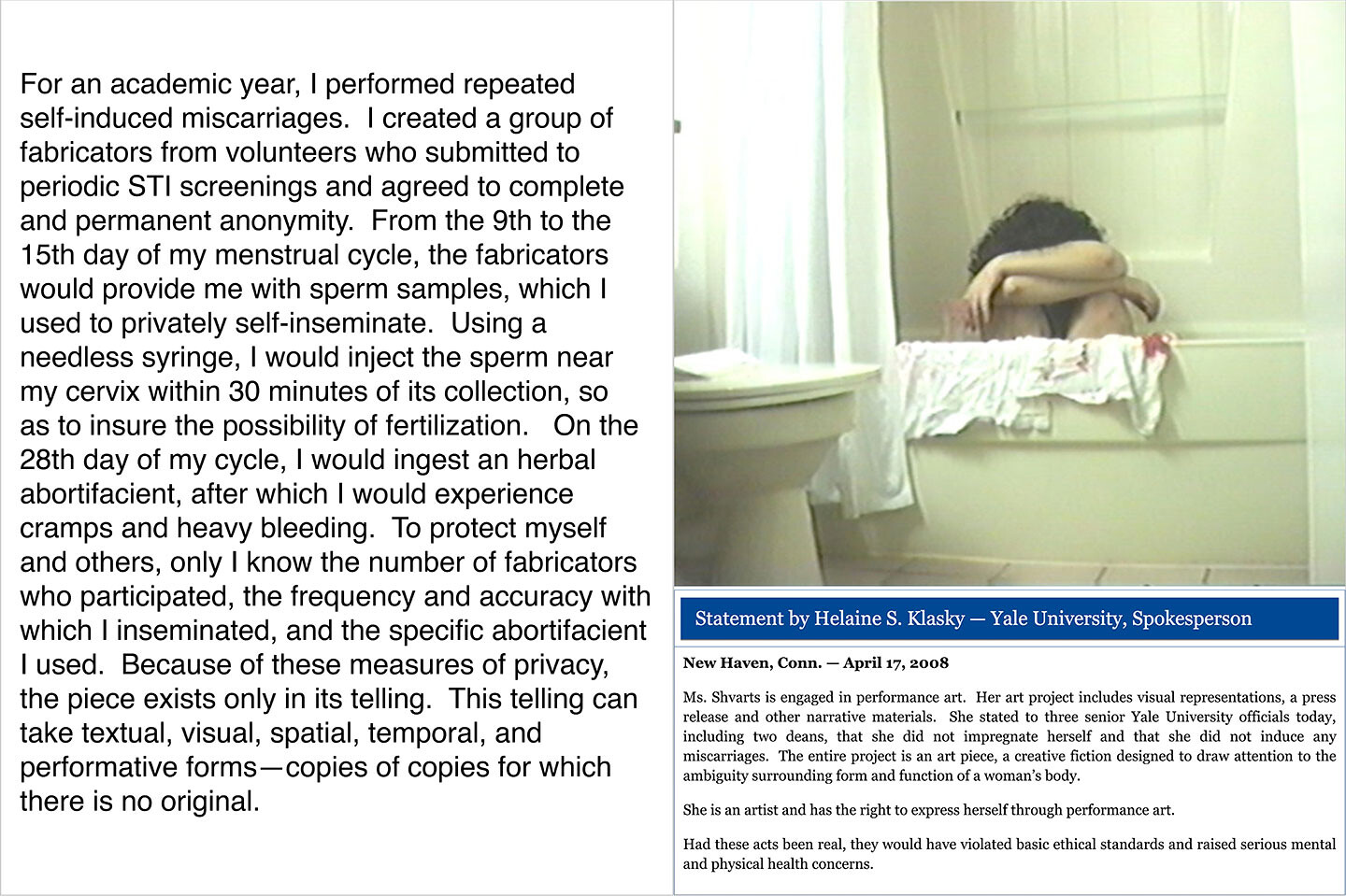

No wonder philosophers have asked whether gestators are persons.5 It seems impossible that a society would let such grisly things happen on a regular basis to entities endowed with legal standing. Given the biology of hemochorial placentation, the fact that so many of us endowed with “viable” wombs are walking around in a state of physical implantability—no Pill, no IUD—ought by rights to be regarded as the most extraordinary thing. To be sure, it has been relatively straightforward in many parts of the world to stop gestating at the very beginning of the process, simply because an unremarkable—even unnoticed—miscarriage occurred, or because the gestator has had access (through a knowledgeable friend) to abortifacients. In 2008, Aliza Shvarts self-inseminated with fresh sperm and then “self-aborted,” over and over again, every month for nine months, by swallowing pills, as a kind of art project.6 I’m curious what that perverse start–stop labor experiment was like. Shvarts’s true, nondefensive thoughts on the matter are unfortunately obliterated by a wall of right-wing bellowing. Unsurprisingly, given that one would expect to feel good upon being extricated from a nonstop job one isn’t willing to do, in general the experience of termination generates feelings of relief and cared-for-ness. As Erica Millar evidences in Happy Abortions, sustained negative emotions are extremely rare in connection with having an abortion.7

Aliza Shvarts, Posters, 2008/2017. Performance documentation (score, still, and official university statement) from Untitled [Senior Thesis] (2008), inkjet prints on paper, 18in x 24in. In response to the project being censored by Yale University, Shvarts did not show any visual documentation of Untitled [Senior Thesis] for 10 years. It is visible now only through the lens of her other works. Courtesy of artist.

Gestational Fix

Pregnancy has long been substantially techno-fixed already, when it comes to those whose lives really “matter.” Under capitalism and imperialism, safer (or, at least, medically supported) gestation has typically been the privilege of the upper classes. And the high-end care historically afforded to the rich when they gestate their own young has lately been supplemented by a “technology” that absorbs 100 percent of the damage from the consumer’s point of view: the human labor of a “gestational surrogate.” Surrogacy, as news media still report, began booming globally in 2011. Around 2016, the industry began suffering a series of setbacks: Thailand and Nepal banned surrogacy altogether for the foreseeable future, and other major hubs (India, Cambodia, and Mexico) legislated against all but “altruistic” heterosexual surrogacy arrangements. Nevertheless, there are still privately registered, profit-making “infertility clinics” on every continent, listing surrogates for hire who will remain, so they say, genetically entirely unrelated to the babies that customers carry away at the end of the process. For, just as the cannier commentators predicted, surrogacy bans do not halt but actually fuel the baby trade, rendering gestational workers far more vulnerable than before.8

Surrogacy bans uproot, isolate, and criminalize gestational workers, driving them underground and often into foreign lands, where they risk prosecution alongside their bosses and brokers, far away from their support networks. In July 2018, thirty-three pregnant Cambodians were detained and charged in Phnom Penh, together with their Chinese boss, for “human trafficking offences.”9 Separately, one Mumbai-based infertility specialist began recruiting surrogate workers from Kenya immediately after India’s Supreme Court decision against commercial and homosexual surrogacy. Through in vitro fertilization, he implants the Kenyans with embryos belonging to his gay clients. Pregnant, these contractors are flown back to Nairobi after twenty-four weeks’ monitoring in India. The babies are birthed in designated hospitals in Nairobi, where clients can pick them up. The doctor maintains that he has not broken Indian law, because he has not interacted with gay clients within that territory: all he has provided, technically, is IVF for Kenyan “health care” seekers. In other words, clinicians simply jump through legal loopholes by moving surrogate mothers across borders, exposing surrogate mothers to greater risks while expanding and diversifying their business partnerships worldwide.10

The trend toward commercial surrogacy does not constitute a qualitative transformation in the mode of biological reproduction that currently destroys (as those aforementioned mortality statistics show) so many adults’ lives. In fact, capitalist biotech does nothing at all to solve the problem of pregnancy per se, because that is not the problem it is addressing. It is responding exclusively to demand for genetic parenthood, to which it applies the logic of outsourcing. While the development remains uneven and tentative, it is clear that what capitalism is proposing by alienating and globalizing gestational surrogacy in this way is, as usual, an option involving moving the problem around. Pregnancy work is not so much disappearing or getting easier as crashing through various regulatory barriers onto an open market. Let the poor do the dirty work, wherever they are cheapest (or most convenient) to enroll.

And no wonder, given that the ground for such a development was already being laid as early as the late nineteenth century, when large swathes of the colonial, upper-class, frequently women-led eugenics movement in Europe and North America argued that the best way to realize pregnancy’s promise—namely, a thriving future “race” achieved through sexual “virtue” and white-supremacist “hygiene”—was for the state to economically discipline all sexual activity unconducive to that horizon.11 As good social democrats, these “feminist” progressives wanted a nation-state that was duty-bound to feed, shelter, clothe, educate, and train the gestational laborers present within its territory, and (especially) the products of that gestational labor.12 Since this was then, and remains now, a costly sounding proposition, a set of enduring ideas and policies were propagated around the turn of the century, according to which, as far as metropolitan proletarians were concerned, having babies spells financial irresponsibility and surefire ruin in and of itself—especially out of wedlock. The same discouragement applied, more or less, to nonwhite (Italian, Irish, Arab) immigrants on the eastern American seaboard. Lumpenproletarian populations in “the colonies” (notably India) faced more hands-on methods, including (famously) sterilization. Meanwhile, curiously, for families of the capitalist class, having babies represents a virtuous and vital investment guaranteeing their—and the very economy’s—good fortunes.

“That there is even a relationship between material well-being and childbearing is a twentieth-century, middle-class, and to some extent white belief,” historian Laura Briggs insists.13 Nevertheless, it’s been but a series of logical steps from that hegemonic notion of reproductive meritocracy to the beginnings of the pregnancy “gig economy” we can glimpse today. In unprecedentedly literal ways, people make babies for others in exchange for the money required to underwrite morally, as well as materially, their own otherwise barely justifiable baby-having. It’s not quite accurate, though, to say that the basic ideas of early eugenicist reproductive policy have resurfaced in late capitalism—or even to say that they’ve survived. Rather, as W. E. B. Du Bois lays out in Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880—or Dorothy Roberts in Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty—these interlocking logics of property and sub-humanity, privatization, and punishment, form the template that organized capitalism in the first place and sustains it as a system.14 Dominant liberal-democratic discourses that hype a world of postracial values and bootstrap universality only serve to render dispossessed populations the more responsible for their trespass of being alive and having kids while black. Stratification is self-reproducing and not designed to be resolved.

It is still useful to call out contemporary iterations of eugenic common sense for their face-value incoherence; still legitimate to point out (the hypocrisy!) that even as urban working-class and black motherhood continues to come under attack, the barriers to black and working-class women’s access to contraception and abortion grow steadily more formidable. The positive “choice” to “freely invest” in having a baby is one that numerous laws are literally forcing many people to make, with dire and frequently fatal results. Obstetric care in India remains to this day among the most scant in the whole world—even though India exports and offers obstetric medical care to customers around the world. Such contradictions, we know, are part and parcel of capitalist geopolitical economy, which needs populations to extinguish in the process of making others thrive. It’s not just life that is a sexually transmitted disease, as the old joke has it. Birth justice campaigners know, as indeed AIDS activists knew in the 1980s and 1990s, that it is death that sex spreads, simultaneously, in the context of for-profit health care.

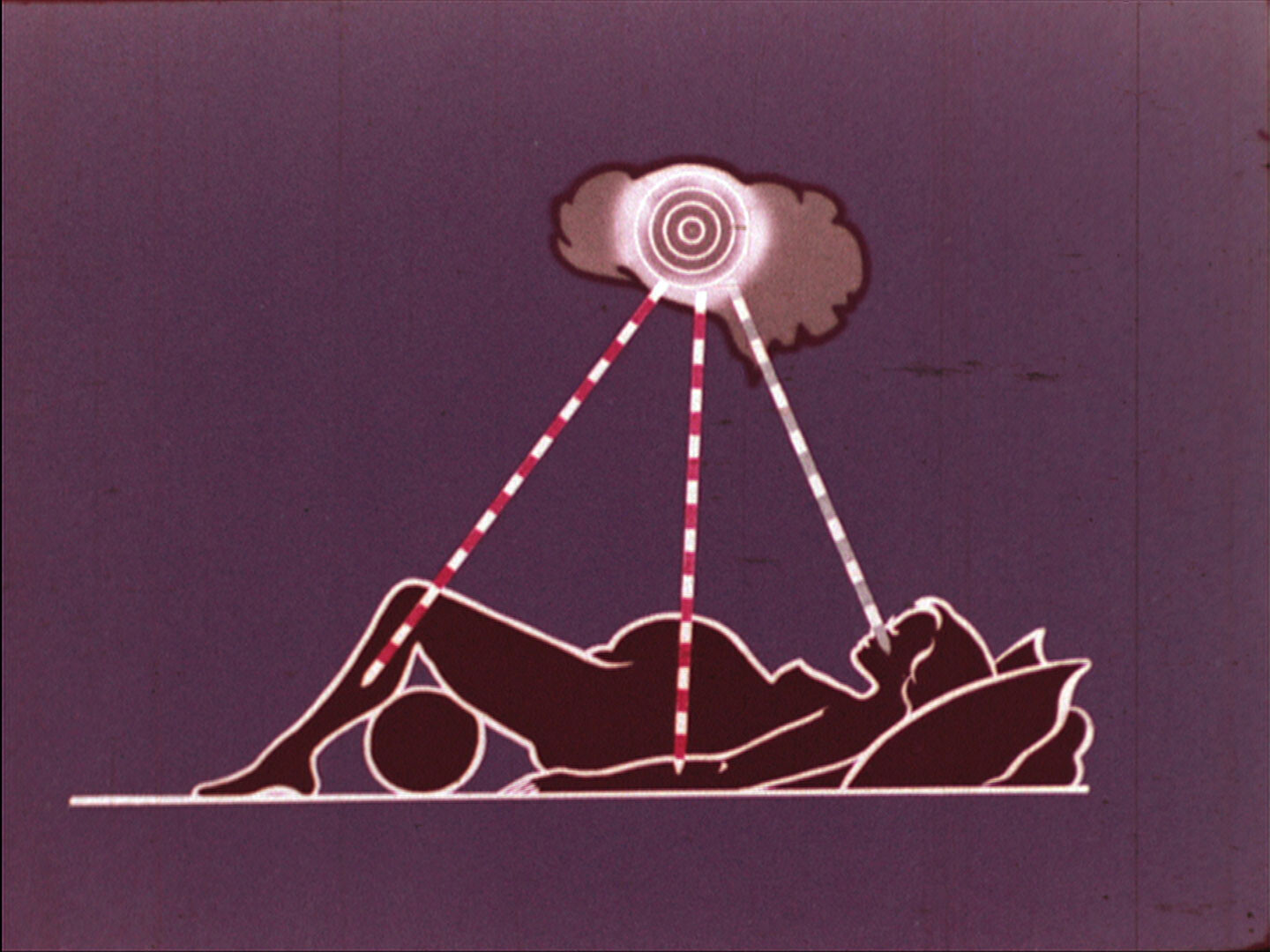

However, this depressing state of affairs hasn’t ever been the whole story. From Soviet mass holiday camps for pregnant comrades, to Germany’s inventive (albeit doomed) “twilight sleep” methods—designed to completely erase the memory of labor pain—human history contains a plethora of ambitious ideologies and technological experiments for universally liberating and collectivizing childbirth. It’s admittedly an ambivalent record. Irene Lusztig, director of a beautiful 2013 archival film on this subject, has understandably harsh words for the various early-twentieth-century rest-camps and schools of childbirth she discusses. But, she suggests, you have to hand it to them—even the most wrongheaded of textbooks written a century ago at least stated the problem to be solved in uncompromising terms: “Birth injuries are so common that Nature must intend for women to be used up in the process of reproduction, just as a salmon die after spawning.”15 Well if that’s what Nature intends, the early utopian midwives and medical reformers featured in The Motherhood Archives responded: then Nature is an ass. Why accept Nature as natural?16 If this is what childbirth is “naturally” like, they reasoned, looking about them in the maternity wards of Europe and America, then it quite obviously needs to be denatured, remade.17 Easier said than done. Pioneering norms of fertility care based on something like cyborg self-determination have turned out to be a moving target. The exceptionality and care-worthiness of gestation remains something that has to be forcibly naturalized, spliced in against the grain of a “Nature” whose fundamental indifference to death, injury, and suffering does not, paradoxically, come naturally to most of us.

Moreover, many of these efforts to emancipate humanity from gestational “Nature” have claimed the name of “Nature” for their cause, too. For instance, the turn to so-called “natural childbirth”—which earned such fiery contempt from Shulamith Firestone in 1970 for being bourgeois—more accurately stands for a regimen full of carefully stylized gestational labor hacks and artifices, a suite of mental and physical conditioning that may be billed as “intuitive” but which nevertheless take time and skill to master. Natural childbirth has never gone entirely out of fashion and is still extremely popular among diverse social classes.18 And while particular subdoctrines of natural childbirth continue to come under well-justified fire wherever they stray into mystification, the broader free-birthing movement’s foundational critique of just-in-time capitalist obstetrics and its colonial-patriarchal history—whereby midwives, witches, and their indigenous knowledges were expelled from the gestational workplace—is hard to fault.19

Likewise, I have absolutely no quarrel with the trans-inclusive autonomist midwives and radical doulas, the ones (unlike ProDoulas—see note 23) lobbying for their work to become a guaranteed form of free health care.20 I have no quarrel with “full-spectrum” birth-work that supports people of all genders through abortion, miscarriage, fertility treatments, labor, and postpartum, often operating outside of biomedical establishments, spreading bottom-up mutual aid, disseminating methods geared toward achieving minimally (that is, sufficiently) medicated, maximally pleasurable reproduction.21 Quite the contrary: power to them. With their carefully refined systems of education, training, and traditional lay science, they are, in their own way, creating a nature worth fighting for.22 It can hardly be an accident that, as anyone who spends time in midwifery networks will realize, so many of them are anti-authoritarian communists.23

Few people consciously want babies to be commodities. Yet baby commodities are a definite part of what gestational labor produces today. Given the variety of organizing principles that can apply to the baby assembly line, it is ahistorical (at best) to claim that what we produce when we’re pregnant is simply life, new life, love, or “synthetic value”: the value of human knitted-togetherness.24 Such claims are unsatisfying, in the first instance, because they fail to account for gestators who do not bond with what’s inside them. And they can’t fully grasp altruistic surrogacy, where the goal is explicitly to not generate a bond between gestator and baby in the course of the labor (even if some surrogates do attach and sometimes propose a less exclusive, open adoption–style parenting model after they’ve given birth). The related, philosophically widespread, claim that social bonds are grounded biologically in pregnancy—what some call the “nine-month head-start” to a relationship—is ultimately incomplete.25 The better question is surely: a head-start to what? What type of social bonds are grounded by which approach to pregnancy?

Clearly, if I am gestating a fetus, I may feel that I am in relationship with that (fetal) part of my body. That “relationship” may even ground the sociality that emerges around me and the infant if and when it is born, assuming that we continue to cohabit. But I may also conceptualize the work in a completely different way—grounding an alternate social world. I may never so much as see (or wish to see) my living product; am I not still grounding a bond with the world through that birth? For that matter, people around me may fantasize that they are in a relationship with the interior of my bump, and they will even be “right” insofar as the leaky contamination and synchronization of bodies, hormonally and epigenetically, takes place in many (as yet insufficiently understood) ways. We simply cannot generalize about “the social” without knowing the specifics of the labor itself. And, regardless of the “ground” the gestational relationship provides, the fabric of the social is something we ultimately weave by taking up where gestation left off, encountering one another as the strangers we always are, adopting one another skin-to-skin, forming loving and abusive attachments, and striving at comradeship. To say otherwise is to naturalize and thus, ironically, to devalue that ideological shibboleth “the mother-fetus bond.” What if we reimagined pregnancy, and not just its prescribed aftermath, as work under capitalism—that is, as something to be struggled in and against toward a utopian horizon free of work and free of value?

Irene Lusztig, The Motherhood Archives, 2013. 91 min, HD video, 16 mm, and archival film.

Terms of Engagement

What is commercial gestational surrogacy, in concrete terms? It is a means by which capitalism is harnessing pregnancy more effectively for private gain, using—yes—newly developed technical apparatuses, but also well-worn “technologies” of one-way emotional and fleshly service—well-beaten channels of unequal trade. Surrogacy is a logistics of manufacture and distribution where the commodity is biogenetic progeny, backed by “science” and legal contract. It’s a booming, ever-shifting frontier whose yearly turnover per annum is unknown but certainly not negligible: “a $2bn industry” was the standard estimate quoted in 2017.26 One freelance international broker alone, Rudy Rupak, who set up the medical tourism outfit PlanetHospital, described himself as “an uncle to about 750 kids around the globe” before he was convicted for fraud in 2014. It is safe to say that several thousand babies every year are seeing the light of day and immediately swapping hands in a fast-changing number of legislatures that may or may not (at the time of publication) include California, Ukraine, Russia, Israel, Guatemala, Iran, Mexico, Cambodia, Thailand, India, Laos, and Kenya.

Even outside of academia, with its publishing time constraints, scholars stand little chance of capturing changes in the landscape of commercial surrogacy as they happen. “With Cambodia closing its doors to surrogacy,” supplies one blog tentatively, “Laos will possibly become the next destination for these reproductive services,” at least for a few months, until Laotian legislators too crack down.27 In a breakthrough for the far-right Israeli homophobia lobby, it was announced that the enormous industry in Israel tailoring its surrogacy services specifically to gay men would now be shut down from summer 2018 on, sparking mass protests.28 By contrast, one legislature poised to legalize compensated third-party gestation for clients of all sexual orientations in 2019 is the state of New York, which numbers among just four states in the United States to still ban any surrogacy arrangement more than three decades after “Baby M” became the focus of debate. The government of the United Kingdom, too, is now undertaking a three-year inquiry into its rules determining parentage, as a consequence of which “laws could be reformed to remove automatic rights” from the person who gestates or genetically donates toward a baby—that is, from the individuals one shrill article in The Telegraph pre-emptively calls “the parents” (specifically, “birth parents”).29

The basics: a commercial gestational surrogate receives a fee, the disbursement of which (across the trimesters) varies by country. The surrogate’s capacity to undertake a pregnancy is essentially leased to one or more infertile individuals, who subsequently own a stake in the means of production, namely, the surrogate’s reproductive biology. This grounds a corresponding claim upon the hoped-for product, living progeny, which more often than not denotes genetic progeny, although donor gametes are also used. Assuming the pregnancy has gone smoothly, the surrogate is contractually bound to relinquish all parental claims soon after the delivery, which proceeds, in a disproportionate number of cases, by caesarean section.

Commercial or not, gestational surrogacy is the practice of arranging a pregnancy in order to construct and deliver a baby that is “someone else’s.” So then, if that is what this book is about, this is a book about an impossibility. An impossibility, how so? I mean something which all the best parents on earth (particularly “adoptive” ones) already know, namely, that bearing an infant “for someone else” is always a fantasy, a shaky construction, in that infants don’t belong to anyone, ever. Obviously, infants do belong to the people who care for them in a sense, but they aren’t property. Nor is the genetic code that goes into designing them as important as many people like to think; in fact, as some biologists provocatively summarize the matter: “DNA is not self reproducing … it makes nothing … and organisms are not determined by it.”30 In other words, the substance of parents gets scrambled. Their source code doesn’t “live on” in kids after they die any more than that of nonparents. Donna Haraway extrapolates from this that “there is never any reproduction of the individual” in our species, since “neither parent is continued in the child, who is a randomly reassembled genetic package,” and, thus, for us, “literal reproduction is a contradiction in terms.”31 There is only degenerative and regenerative co-production. Labor (such as gestational labor) and nature (including genome, epigenome, microbiome, and so on) can only alchemize the world together by transforming one another. We are all, at root, responsible, and especially for the stew that is epigenetics. We are the makers of one another. And we could learn collectively to act like it. It is those truths that I wish to call real surrogacy, full surrogacy.

Such a move is inspired by utopian traditions—those of various socialist biologists, queer and transfeminist scientists, antiracists, and communists—that have speculated about what babymaking beyond blood, private coupledom, and the gene fetish might one day be. These traditions remain utopian because surrogacy today can be everything from severely banal to disturbingly ghoulish. Nightmarish mishaps within the transnational choreography of surrogacy have repeatedly occurred, and although they were so far, in each case, eventually resolved, they have prompted lurid mass condemnation of a sector that creates babies only to consign them to the limbo of statelessness, the helplessness of orphanhood, the predations of traffickers, the acquisitiveness of other random child-starved couples, and other calamities. Amid significantly less fanfare, surrogates have died from postpartum complications.

That covers what’s “ghoulish” in the picture. As far as “banal” goes, notwithstanding the myriad news stories about sensational individual cases, the unconventional gestational provenance of many newborn babies who have been collected from fertility clinics (from “host” uteruses) passes overwhelmingly under the radar. Being a “surrobaby” goes unremarked upon on birth certificates and is frequently not disclosed in the children’s social milieus. There is a gap, an aporia, between the familiarity of millions of primetime television viewers with surrogacy, where surrogacy is an extravagant possibility happening “out there” to other people, and the fact that “surro-babies” pass among us in their thousands, invisibly. The everyday flow of surrogacy among populations remains unknown to many, since it barely troubles the surface of the spectacle that is the conventional nuclear family.

At the same time, there are countless books in existence on the topic, the vast majority of which are bioethical in focus, which is to say they set out to question surrogacy by discussing the saleability either of wombs or of “life itself” from a moral and humanitarian standpoint. Others present thoughtful and granular studies of the sales already taking place by focusing variously on things like the role of religious faith in surrogacy32; its patterns of racial stratification and (thwarted) migration33; the role of shared metaphors in establishing motherhood34; the specificity of these in LGBTQ kinmaking ontologies35; the neocolonial aspects of the industry (a “transnational reproductive caste system”)36; discourse norms on online surrogacy forums37; prehistories of “pro-natal technologies in an anti-natal state” (i.e., the significance of sterilization policy previously endured by groups now recruited to gestate for others)38; and other localized features of the market, such as the boom among US “military wives” who make use of their high-end medical insurance packages to gestate, as boutique freelancers, while their husbands are away on deployments.39

What is the point of this book? Full Surrogacy Now is not a book primarily derived from case studies. Nor, as you’ve seen, does it argue that there is something somehow desirable about the “surrogacy” situation such as it is. It presents brief histories of reproductive justice, anti-surrogacy, and saleswomanship at one particular clinic—but its main distinction, or so I hope, is that it is theoretically immoderate, utopian, and partisan regarding the people who work in today’s surrogacy dormitories. The aim is to use bourgeois reproduction today (stratified, commodified, cis-normative, neocolonial) to squint toward a horizon of gestational communism. Throughout, I assume that the power to get to something approaching such a horizon belongs primarily to those who are currently workers—workers who probably dream about not being workers—specifically, those making and unmaking babies.

Although I do not call for a reduction40 in baby-making, this book seeks to land a blow against bourgeois society’s voracious appetite for private, legitimate babies (“at least, healthy white [ones],” as Barbara Katz Rothman specifies, presumably using the word “healthy,” here, with irony—to signify absence of disability).41 The regime of quasi-compulsory “motherhood,” while vindicating itself in reference to an undifferentiated passing-on of “life itself,” is heavily implicated in the structures that stratify human beings in terms of their biopolitical value in present societies. If, as Laura Mamo finds in her survey of pregnancies in the queer community in the age of technoscience, the new dictum is “If you can achieve pregnancy, you must procreate,”42 it is a dictum that, like so many “universal” things, disciplines everybody but really only applies to a few (the ruling class). And, while the questions of LGBTQ and migrant struggle are sometimes separated from class conflict, any understanding of this system of “economic” reproductive stratification will be incomplete without an account of the cissexist, anti-queer, and xenophobic logics that police deviations from the image of a legitimate family united in one “healthy” household.43 Drug users, abortion seekers, sexually active single women, black mothers, femmes who defend themselves against men, sex workers, and undocumented migrants are the most frequently incarcerated violators of this parenting norm. They have not been shielded by the fact that the Family today is now no longer necessarily heterosexual, with states increasingly making concessions to the “homonormative” household through policy on gay marriage.44

Gestational Commune

“Full surrogacy now,” “another surrogacy is possible”: to the extent that these interchangeable sentiments imply a revolutionary program (as I’d like them to) I’d propose it be animated by the following invitations. Let’s bring about the conditions of possibility for open-source, fully collaborative gestation. Let’s prefigure a way of manufacturing one another noncompetitively. Let’s hold one another hospitably, explode notions of hereditary parentage, and multiply real, loving solidarities. Let us build a care commune based on comradeship, a world sustained by kith and kind more than by kin. Where pregnancy is concerned, let every pregnancy be for everyone. Let us overthrow, in short, the “family.”45

It is admittedly quite hard to imagine the book by me that would do full justice to that remit. Happily, the ideas I’ve just glossed over aren’t new or original and will continue to be refined and concretized for years and years after this. Writing is, of course, an archetypal example of distributed, omni-surrogated creative labor. While the name on the cover of this book is mine, the thoughts that gestated its unfinished contents, like the labors that gestated (all the way into adulthood) the thinkers of those ongoing thoughts, are many. Mario Biagioli puts it well in his essay comparing gestational surrogacy with intellectual plagiarism: “authorship can only be coauthorship.”46

Unabashedly interested in family abolition, I want us to look to waged gestational assistance specifically insofar as it illuminates the possibility of its immanent destruction by something completely different. In other words, I’d like to see a surrogacy worthy of the name; a real surrogacy; surrogacy solidarity. That is the reason for flagging this one particular multisited project of capitalist reproduction; not the fact that it is intensive, or unique. I want others to help me read surrogacy against the grain and thereby begin to reclaim the productive web of queer care (real surrogacy) that Surrogacy™ is privately channelling, monetizing, and, basically, stealing from us.

I’ll wager there is no technological “fix” for the violent predicament human gestators are in. Technologies for ex utero babymaking might be a good idea, and the same goes for more ambitious research and development in the field of abortion and contraception. But, fundamentally, the whole world deserves to reap the benefits of already available techniques currently monopolized by capitalism’s elites. It is the political struggle for access and control—the commoning or communization of reprotech—that matters most. It is certainly going to be up to us (since technocrats wouldn’t do it for us, or hand it over to us if they did) to orchestrate intensive scientific inquiry into ways to tweak bodily biology to better privilege, protect, support, and empower those with uteruses who find themselves put to work by a placenta.

Far from a cop-out, saying there is no miracle fix for gestation—except seizing the means of reproduction—should light a fire under our desires to abolish the (obstetric) present state of things. Beyond the centuries-long circular debate about whether our pregnancies are “natural” or “pathological,” there is, I know, a gestational commune—and I want to live in it.

Elena Ferrante, The Days of Abandonment (Penguin Press, 2005), 91.

Chikako Takeshita, “From Mother/Fetus to Holobiont(s): A Material Feminist Ontology of the Pregnant Body,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3, no. 1 (2017).

Suzanne Sadedin, “Why Pregnancy is a Biological War Between Mother and Baby,” Aeon, August 4, 2014 →.

Susan Bordo, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (University of California Press, 1993).

Ana Grahovac, “Aliza Shvarts’s Art of Aborting: Queer Conceptions and Resistance to Reproductive Futurism,” MAMSIE 5, no. 2: 1–19.

Erica Millar, Happy Abortions: Our Bodies in the Era of Choice (Zed Books, 2017), 4.

Carolin Schurr, “‘Trafficked’ into a better future? Mexico two years after the surrogacy ban,” HSG Focus magazine, Universität St. Gallen, January 2018.

Associated Press, “Pregnant Cambodian Women Charged with Surrogacy and Human Trafficking,” July 6, 2018.

Sharmila Rudrappa, “How India’s Surrogacy Ban Is Fuelling the Baby Trade in Other Countries,” Quartz, October 24, 2017.

See for instance Michelle Murphy’s succinct overview of Margaret Sanger’s trajectory in Michelle Murphy, “Liberation through Control in the Body Politics of U.S. Radical Feminism,” in The Moral Authority of Nature, eds. Lorraine Daston and Fernando Vidal (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Duke University Press, 2004).

Laura Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics (University of California Press, 2017), 127.

W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (Free Press, 1992); Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (Vintage, 1999).

Irene Lusztig, The Motherhood Archives, Komsomol films, 2013, 91 minutes.

Michelle Stanworth writes: “The term ‘natural’ can hardly be applied to high rates of infertility exacerbated by potentially controllable infections, by occupational hazards and environmental pollutants, by medical and contraceptive mismanagement … (and thus,) the thrust of feminist analysis has been to rescue pregnancy from the status of the natural.” Michelle Stanworth, “The Deconstruction of Motherhood,” in Reproductive Technologies: Gender, Motherhood and Medicine, ed. Michelle Stanworth (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 10–35, 34.

The view that reproductive autonomy denatures Nature—be that a good or bad thing—is alive and well. On May 25, 2018, in the wake of the Republic of Ireland’s referendum repealing the ban on abortion in that country, the prominent British philosopher John Milbank (@johnmilbank3) tweeted: “The terrifying number of women in favour of ‘the right to choose’ is evidence of the drastic denaturing of women that lies perhaps at the very heart of the capitalist and bureaucratic drive to depersonalise.” Meanwhile, xenofeminist theorist Helen Hester has aptly criticized the various other bodies of “naturalist” thought—including ecofeminism—that have also relegated gestators to a romanticized state of disempowerment. Writes Hester: “The apparent suggestion that gestation and labour should be beyond one’s control is particularly troubling.” Helen Hester, Xenofeminism (Polity Press, 2018), 17.

Firestone’s take on the wave of enthusiasm for Grantly Dick-Read, Lamaze, and related “returns to nature” is worth reproducing, despite the force of its contempt leading her prose into sloppiness: “The cult of natural childbirth itself tells us how far we’ve come from true oneness with nature. Natural childbirth is only one more part of the reactionary hippie Rousseauean Return-to-Nature, and just as self-conscious. Perhaps a mystification of childbirth, true faith, makes it easier for the woman involved. Pseudo-yoga exercises, twenty pregnant women breathing deeply on the floor to the conductor’s baton, may even help some women develop ‘proper’ attitudes (as in ‘I didn’t scream once’).” Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex (Verso, 1970/2015), 199.

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (Autonomedia, 2004); Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, Witches, Midwives and Healers, 2nd ed. (Feminist Press, 2010).

The Doulas: Radical Care for Pregnant People, eds. Mary Mahoney and Lauren Mitchell (Feminist Press, 2016).

Alana Apfel, Birth Work as Care Work: Stories from Activist Birth Communities (PM Press, 2016).

In a study of seventeen “natural birth” manuals, geographer Becky Mansfield found that “natural childbirth requires hard and very conscious work.” Becky Mansfield, “The Social Nature of Natural Childbirth,” Social Science & Medicine 66, no 5 (2008): 1093.

Radical doulas have ideological enemies: so-called ProDoulas. Katie Baker has dug up the dirt on the new clique of cut-throat capitalists in the doula industry. Katie J. M. Baker, “This Controversial Company Wants to Disrupt the Birth World,” BuzzFeed, January 4, 2017 →.

Mary O’Brien, The Politics of Reproduction (Unwin Hyman, 1981).

Katharine Dow, “‘A Nine-Month Head-Start’: The Maternal Bond and Surrogacy,” Ethnos 82, no 1 (2017): 86–104.

“Commercial Surrogacy Has Become a $2bn Industry,” The New Indian Express, September 1, 2016.

Paula Gerber, “Arrests and Uncertainty Overseas Show Why Australia Must Legalise Compensated Surrogacy,” The Conversation, November 23, 2016.

Daniel Politi, “Tens of Thousands Protest in Israel Over Denial of Surrogacy Rights for Gay Men,” Slate, July 22, 2018 →.

Olivia Rudgard, “Surrogacy Reform Could Remove Automatic Rights from Birth Parents,” The Telegraph, May 4, 2018 →.

Richard Lewontin and Richard Levins, Biology Under the Influence: Dialectical Essays on Ecology, Agriculture, Health (New York University Press, 2007), 239.

Donna Haraway, Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of Modern Science (Routledge, 1989), 352.

Marcia Inhorn and Soraya Tremayne, Islam and Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Sunni and Shia Perspectives (Berghahn, 2012).

Laura Harrison, Brown Bodies, White Babies: The Politics of Cross-Racial Surrogacy (New York University Press, 2016).

Elly Teman, Birthing a Mother: The Surrogate Body and the Pregnant Self (University of California Press, 2010).

Laura Mamo, Queering Reproduction: Achieving Pregnancy in the Age of Technoscience (Duke University Press, 2007.)

Amrita Banerjee, “Race and a Transnational Reproductive Caste System,” Hypatia 29, no 1 (2013): 113–28.)

Zsusza Berend, The Online World of Surrogacy (Berghahn, 2018).

Amrita Pande, Wombs in Labor: Transnational Commercial Surrogacy in India (Columbia University Press, 2014), 21.

Elizabeth Ziff, “‘The Mommy Deployment’: Military Spouses and Surrogacy in the United States,” Sociological Forum 32, no. 2 (2017).

My engagement with “make kin, not babies” can be found in the article “Cthulhu Plays No Role For Me,” Viewpoint magazine, 2017 →. See Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016); and the subsequent revision of Haraway’s argument, which continues our ongoing conversation, in Making Kin, Not Population: Reconceiving Generations, eds. Donna Haraway and Adele Clark (Prickly Paradigm Press, 2018).

Barbara Katz Rothman, Recreating Motherhood (Rutgers University Press, 2000), 39.

Mamo, Queering Reproduction, 228.

Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (Zone Books, 2017); Laura Briggs, Somebody’s Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption (Duke University Press, 2012); Anglea Mitropoulos, Contract and Contagion: From Biopolitics to Oikonomia (Minor Compositions, 2012); Shelley Park, “Adoptive Maternal Bodies: A Queer Paradigm For Rethinking Mothering?” Hypatia 21, no 1 (2006): 201–26.

Against Equality: Queer Revolution, not Mere Inclusion, ed. Ryan Conrad (AK Press, 2014).

It is to Michelle O’Brien that everyone should turn for a history of the positive and negative movements of “family abolition” throughout capitalist history: Michelle Esther O’Brien, “To Abolish the Family: Periodizing Gender Liberation in Capitalist Development,” Endnotes 5, forthcoming. Writes O’Brien in her draft manuscript: “Abolishing the family only finds coherence today when joined with the movement against the other dominant means of working-class reproduction: the struggles to abolish the capitalist wage and the racial state … Abolishing the family is the mass decommodification, collectivization and universal access to the material necessities of generational and daily reproduction.”

Mario Biagioli, “Plagiarism, Kinship and Slavery,” Theory, Culture & Society 31, no. 2/3 (2014): 84.

Category

This text is an excerpt from the introduction to Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family by Sophie Lewis, published by Verso in May 2019.

_Section_of_human_placentaWEB.jpg,1600)