One hears time and again that contemporary art is elitist because it is selective, and that it should be democratized. Indeed, there is a gap between exhibition practice and the tastes and expectations of the audience. The reason is simple: the audiences of contemporary art exhibitions are often local, while the exhibited art is often international. This means that contemporary art does not have a narrow, elitist view, but, on the contrary, a broader, universalist perspective that can irritate local audiences. It is often the same kind of irritation that migration provokes today in Europe. Here we are confronted with the same phenomenon: the broader, internationalist attitude is experienced by local audiences as elitist—even if the migrants themselves are far from belonging to any kind of elite.

Cover art for Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Designed by David Pearson for Penguin’s Great Ideas series, vol. 3 (2008).

Any genuine contemporary exhibition is not an exhibition of local art in the international context, but rather an exhibition of international art in the local context. The local context can obviously be seen as already given, already familiar to the local audience, whereas the context of an international art exhibition is necessarily constructed by the curator. Every exhibition is, if you will, a montage in that it does not depict any real local context in which art functions, but is always artificial through and through. There are more than enough examples of how this artificiality can cause irritation. In “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” Walter Benjamin famously equals the exhibition of an object with its reproduction, and defines the “exhibition value” of the artwork as an effect of its reproducibility.1 Both reproduction and exhibition are operations that remove the artwork from its historical place—from its “here and now”—and send it along a path of global circulation. Benjamin believes that as a result of these operations, the artwork loses its “cult value,” its place in ritual and tradition, its aura. Here, the aura is understood as the artwork’s inscription in the historical context to which it originally belongs, while the loss of aura results from its removal from that world of lived experience. The copy refers to the original but does not truly present it. The same can be said about the exhibited artwork: it refers to its original context, but actually prevents the exhibition visitor from experiencing it. Having been liberated, isolated from its original environment, the artwork remains materially self-identical but loses its historical place, and thus, its truth.

Almost contemporaneously, Martin Heidegger writes in his “Origin of the Work of Art”: “When a work is brought into a collection or placed in an exhibition we say also that it is ‘set up.’ But this setting up differs essentially from setting up as erecting a building, raising a statue, presenting a tragedy at a holy festival.”2 Heidegger differentiates again between an artwork inscribed into a certain historical and/or ritual space and time, and an artwork that is merely exhibited at a certain place but removable, thus without context. However, in his later writing Heidegger begins to stress the technological, artificial character of our relation to the world. For Heidegger, the subject does not have an ontologically guaranteed outside position vis-à-vis the world. Rather, this position is artificially constructed by modern technology. Technology creates the framing, or Gestell (apparatus) that allows one to position as a subject and experience the world as an object, as an image.3 This framing defines our relationship to our environment, and invisibly guides our experiences of it. However, as Heidegger describes, this apparatus remains concealed from us because it opens the world to our gaze as something that is familiar, “natural.”

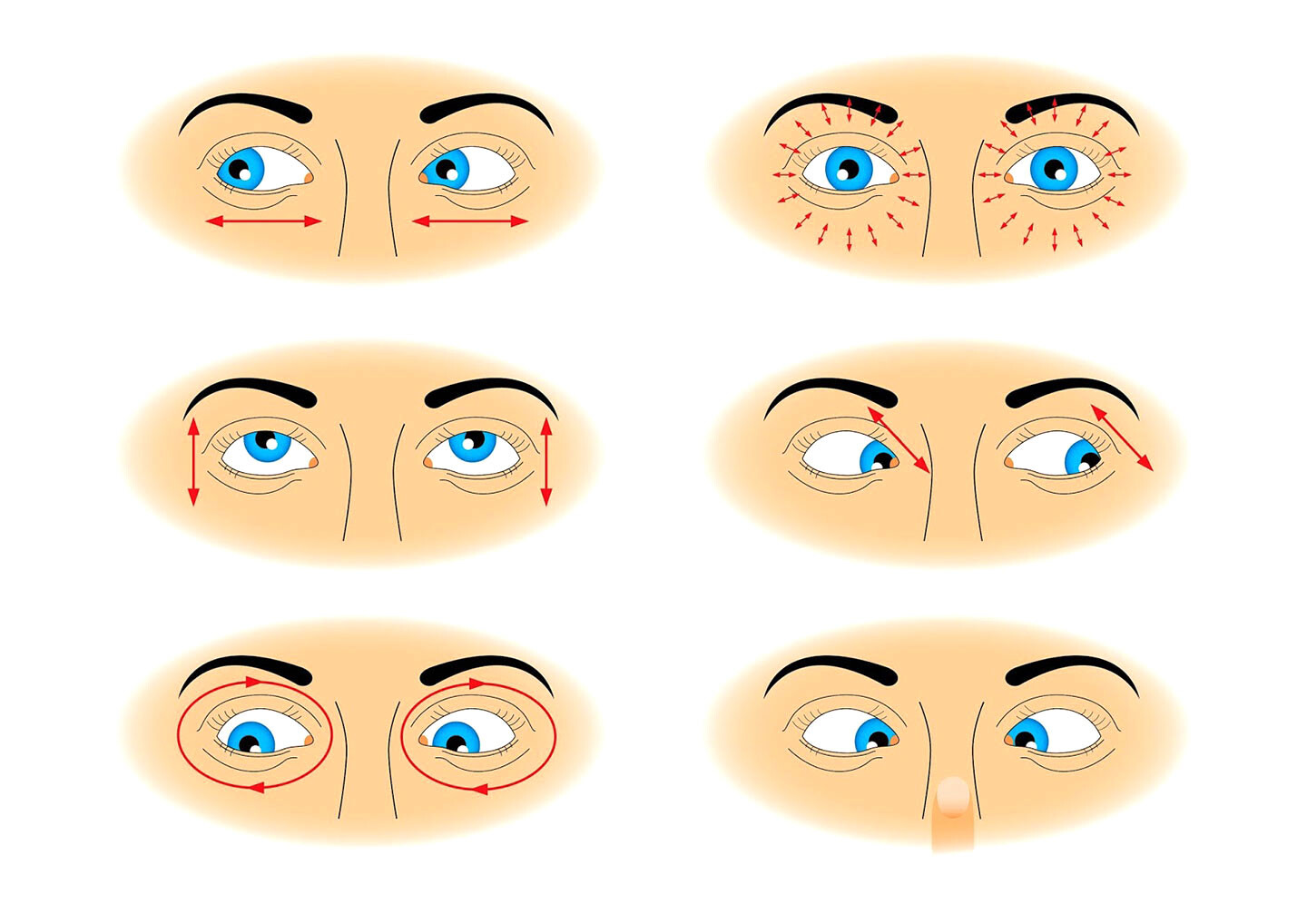

Instructions for eye yoga exercises aimed at relieving eyesight screen stress.

I would argue that exhibitions defamiliarize local contexts and reveal their Gestell—the way in which their framings operate. This is where the exhibition begins to be understood not as a pure act of presenting, but as the presentation of presenting, a revelation of its own strategy of framing. In other words, the exhibition does not only present certain images to our gaze, but also demonstrates the technology of presenting, the apparatus and structure of framing, and the mode in which our gaze is determined, oriented, and manipulated by this technology. When we visit an exhibition, we do not only look at the exhibited images and objects, but also reflect on the spatial and temporal relationships between them—the hierarchies, curatorial choices, and strategies that produced the exhibition, and so forth. The exhibition exhibits itself before it exhibits anything else. It exhibits its own technology and its own ideology. In fact, the framing is nothing but an amalgamation of technology and ideology.

In relationship to the exhibition, one can speak of two different types of gazes, which we can call the frontal gaze and the gaze from within. When we look at an image—whether a painted image, an image on a computer screen, or a page in a book—we use the frontal gaze, which allows us to scrutinize the object in all its aspects. If we interrupt the process of contemplation, the frontal gaze allows for a new process to begin from the same point in space at which we stopped. But this precision and stability of vision is achieved by disregarding the context of our visual experience: we are in a condition of self-oblivion, detached from the outside world, absorbed and captivated by the object of our contemplation.

However, when we visit a new place—a new city or country, for example—we do not just concentrate on a particular object or series of objects; instead, we look around. In so doing, we become very aware of our specific position. The image of the new place is not in front of us—rather, we are inside of it. This means that we cannot grasp the new place in its totality and in all its nuance. The gaze from within is always a fragmentary one. It is not panoramic, as we can see only what is in front of us at any moment. We know we are inside a certain space, but we cannot visualize this knowledge in its entirety. Furthermore, this gaze is also fragmentary because it cannot be stabilized in time. If we were to visit the same place later, we could never reproduce the same trajectory, the same history of our own gaze. And while this applies to visiting a new place, the same can also be said of a familiar place: it is always seen from within. It is visible and known, though not necessarily visualizable or reproducible. The same can be said of an exhibition that is always seen from within.

In our time, considering the Gestell—the technological framing of our view of the world—one likely thinks of the internet before thinking of exhibitions. However, the gaze of an ordinary internet user is a strictly frontal gaze, concentrated on the screen. In using the internet, its hardware and software—its Gestell—remain concealed to users. The internet frames the world for its user, but it does not reveal its own framing. That opens a possibility for the exhibition of art, and, more generally, for data, that circulates on the internet. Such a form of exhibition is able to thematize the internet’s hardware and software, thus revealing its hidden mechanisms of distribution and presentation. Making such rules of selection explicit subjects them at the same time to questioning and transgression. In other words, the internet comes to be investigated as medium, as material form, not merely as a sum of “immaterial” content.

It is no accident that on the internet, artists function as the so-called content providers. It is, however, quite a shift for the history of Western art. Traditionally, in this context, content available to artists was limited to Jesus Christ, the Holy Virgin, the Christian saints, in addition to the gods of the ancient Greek pantheon and important historical figures. The content providers were the Church and its historical narratives. It follows then that the goal of the artist was to give these contents shape and form, and to illustrate these larger content-providing practices, rather than to produce specific content. Today, however, what is the content that artists provide for the internet? It partially consists of digital representations of artworks, which are merely the artworks that already circulate on the art market.

It is more interesting, however, when artists use the possibilities for producing and distributing art that are specific to the internet. In those cases, they document content that is not covered by mainstream media. It might be too strange or, on the contrary, too trivial to be recorded by standard journalism, or it might be documentation of forgotten or publicly repressed historical events. But it can also be produced by artists themselves—actions, performances, and processes that they initiated and then documented—or it can be total fiction, but where the process of creating the fiction is documented. The cumulative effect of these strategies is not far from nineteenth-century realism, when artists combined conventional approaches to representation with personalized content and subjective interpretation.

A meme joking at the botched restoration of Spanish painter Elias Garcia Martinez’s Ecce Homo (1930).

This is to say that artists on the internet use the means of production and distribution prescribed by the internet to be compatible with protocols that are usually employed to spread information. Twentieth-century formalist art theoreticians such as Roman Jakobson believed that the artistic use of the means of communication presupposes the suspension, or even annulment, of information, which in the context of art means a total absorption of content by form. However, in the context of the internet, the form remains identical for all communication, thus immunizing content from this absorption. The internet reestablishes, on a technical level, the conventions of presenting content dominant in the nineteenth century. Avant-garde artists protested against these conventions for being arbitrary and culturally determined. But a revolt against such conventions makes no sense in the context of the internet, because the conventions have already been inscribed into the technology of the internet itself.

The situation changes, however, when internet data is transposed into offline exhibition spaces. Online, artists operate through combinations of pictures, photos, videos, sound sequences, and text that build into a meta-narrative. In the exhibition space, however, they come to be presented in the form of an installation. Conceptual artists already organized the installation space to convey a certain meaning analogous to the use of sentences in language. After a period dominated by formalism, in the late 1960s conceptual art made artistic practice meaningful and communicative again. Art began to make theoretical statements, to communicate empirical experiences and theoretical knowledge, to formulate ethical and political attitudes, and to tell stories again.

We all know the substantial role that the “linguistic turn” played in the emergence and development of conceptual art. The influence of ideas from sources such as Wittgenstein and French Structuralism was decisive. But the new orientation towards meaning and communication did not make art somehow immaterial or make its materiality less relevant, nor did its medium dissolve into message. On the contrary, every artwork is material, and can only be material. The possibility of using concepts, projects, ideas, and political messages in art was opened by the philosophers of the “linguistic turn” precisely because they asserted the material character of thinking itself. These philosophers understood thinking as a use of language, which is wholly material—a combination of sounds and visual signs. Thus, an equivalence, or at least a parallelism, was demonstrated between word and image, between the order of words and the order of things, between the grammar of language and the grammar of visual space.But if the presentation of art on the internet became standardized, the presentation of art in the exhibition space instead became de-standardized. The reason for this de-standardization is clear: the space of the exhibition is empty; it is not preformatted in the way a webpage or website is. Today, the white cube plays the same role as a blank page performs for modernist writing or a blank canvas for modernist painting. The empty white cube is the zero point of exhibition practice, and thus the constant possibility of a new beginning. This means that the curator has an opportunity to define a specific form, a specific installation, a specific configuration of the exhibition space for the presentation of digital or informational material. Here the question of form becomes central again. The form-giving directive shifts away from individual artworks to the organization of space in which these artworks are presented. In other words, the responsibility for form-giving is transferred from the artists to the curators who use individual artworks as content, only this time within the space that the curators themselves create.

Of course, artists can reclaim their traditional form-giving function, but only if they begin to function as curators of their own work. Indeed, when we visit an exhibition of contemporary art, the only thing that truly remains in our memory is the organization of the spaces of this exhibition, especially if this organization is original and unusual. However, if the individual artworks can be reproduced, the exhibition can be easily documented. And if such documentation is put on the internet, it then becomes content, ready again for a form-giving operation inside the museum. In this way, the exchange between the exhibition space and the internet becomes an exchange between content and form. The exhibition becomes the means through which the relationship between the form and content of art on the internet can be thematized and revealed. Additionally, curated exhibitions of this art can reveal the hidden mechanisms of selection governing the distribution of text and image on the internet.

Screenshot of the twitter account @woreitbetter. This account, previously a blog, compares in real life artworks that are formally similar.

At first glance, the distribution of information on the internet is not regulated by any rules governing its selection. Everyone can use cameras to produce images, to write commentary on them, and to distribute the results with little censorship or selection process. One might think, therefore, that traditional art institutions and their rituals of selection and presentation have become obsolete. Many still see the internet as global and universal, even while it has become increasingly evident that the space of the internet is rather extremely fragmented. Even if all data on the internet is globally accessible, in practice the internet leads not to the emergence of a universal public space but to a tribalization of the public. The reason for that is very simple. The internet reacts to the user’s questions, to the user’s clicks. The user finds on the internet only what he or she wants to find.

The internet is an extremely narcissistic medium—a mirror of our specific interests and desires. It does not show us what we do not want to see. In the context of social media we communicate mostly with those who share our interests and attitudes, whether political or aesthetic. Thus, the non-selective character of the internet is an illusion. The actual functioning of the internet is based on non-explicit rules of selection by which users select only what they already know or are familiar with. Of course, some search engines are able to scrape the entire internet, but they always have particular goals, and are controlled by large corporations and not by individual users. In this respect, the internet is the opposite of, let’s say, an urban space in which we are consistently forced to see what we do not necessarily want to. In many cases we try to ignore these unwanted images and impressions, yet they often provoke our interest and more generally serve to expand our field of experience.

To perform a similar role, we can say that curatorial selection should be a kind of anti-selection, a transgressive selection even. The act becomes relevant when it crosses the dividing lines that fragment the internet and, more generally, our culture. It reinstates the universalist project of modern and contemporary art. Rather than fragmenting the public space, such selection works against it by creating a unified space of representation where the different fragments of the internet come to be equally represented. The creation of such universal spaces was the traditional occupation of the modern art system.

The history of modern world exhibitions began in the nineteenth century, famously with the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. In the art context, the great museums such as the Louvre in Paris, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as well as exhibitions like Documenta in Kassel or numerous biennials, made and still make the claim of presenting the art of the world. Here, individual items are removed from their original contexts and placed in a new artificial context in which images and objects meet historically or “in real life” with each other that otherwise could never have encountered one other. For example, Egyptian gods sit beside Mexican or Inca gods in their respective universes, and in further combination with the unrealized utopian dreams of the avant-garde. These removals and new arrangements call forth uses of violence—such as those in economic and direct military intervention—by demonstrating the forms of order, law, and trade that regulate our world, as well as the ruptures, wars, revolutions, and crimes to which such orders are subjected.

These orders cannot be “seen,” but they can be and are manifested in the organization of the exhibition and in the way it frames art. As visitors, we are not outside this frame, but rather inside it. Through the exhibition, we are exhibited to ourselves and to others. For this reason, the exhibition is not an object, but an event. The aura is not lost when an artwork is uncoupled from its original, local context, but is rather re-contextualized and given a new “here and now” in the event of an exhibition—and thus, in the history of exhibitions. This is why an exhibition cannot be reproduced. One can only reproduce an image or an object placed in front of the viewing subject. However, an exhibition can be reenacted or restaged. In this respect, the exhibition is similar to theatrical mise-en-scène, but with one important difference: exhibition visitors do not remain in front of the stage, but enter the stage to participate in the event.

We live within a system of nation states. However, inside every national culture there are institutions that embody universalist, transnational projects. Among them are universities and large museums. Indeed, European museums were from their inception universalist institutions that attempted to present universal art history rather than specific national art histories. Of course, one can argue that this universalist project reflected the imperial policies of nineteenth-century European states, and to some extent this is true. The European museum system has its origin in the transformation during the French Revolution of objects used by the Church and aristocracy into artworks—objects to be looked at only, rather than used. The French Revolution abolished the contemplation of God as the highest goal of life, and substituted this act with the secular contemplation of “beauty” in material objects. In other words, art as we know it today was produced by revolutionary violence, and was from its beginning a modern form of iconoclasm. This is to say that European museums attempted to aesthetically suspend their own cultural traditions before aestheticizing and suspending non-European cultural traditions.

The goal of the Enlightenment was the creation of the universal and rational world order: a universal state in which every particular culture would be recognized. We are still far from reaching this goal. Our moment is characterized by an imbalance between political and economic powers, between public institutions and commercial practices. Our economy operates on a global level, whereas our politics tend to operate on a local level. However, today’s art system plays a role in symbolically substituting such a universal state for the organization of biennials, Documentas, and other exhibitions claiming to present universal, global art and culture of a non-existent utopian global state. Under current conditions, an exhibition can only be relevant if it constructs such a utopian and universalist context that does not yet exist.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” in Illuminations (New York: Schoken Books, 1969), 257.

Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Basic Writings (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 169.

Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” in Basic Writings (New York: HarperCollins, 2008), 324–5.