Apostrophe is not only the condition of love but an ideal of self-encounter. For the addressee, you are willing to make provisional clarities. For the addressee, you are willing to perform an openness that’s an optimistic brokenness. If you’re lucky, you’re a topos in your own world, although without the apostrophic phantom you cannot exist in the world … If language could pull it off … that is the hope of love.

—Lauren Berlant1La lutte des femmes sera collective ou elle ne sera pas; il ne s’agît pas seulement d’être libre

—Agnès Varda in Les plages d’Agnès (2008)

My love,

When standing in line outside a packed public bathroom assigned to women, I always wonder: What are architects thinking when they unfailingly build an equal number of stalls for both men and women, when it is a proven fact that women need to use the bathroom much more often than men? Desperately, I usually fight the urge to relieve myself and the temptation to dash into the men’s restroom, foreseeing the likely and embarrassing event of running into a male user of the space. In truth, I no longer feel like I need to make a statement about my own gender (or sex?!). Clearly, our bodies do ground our experiences in and of the world, and bear both what we call sex and what we know as gender. This distinction was conceived to explain biological difference in relation to social interpretations of that difference. But it seems to me that this distinction fails to explain why, in spite of or maybe because of the struggle for women’s equality, architects everywhere keep overlooking that women simply need to use the restroom more often than men. Perhaps it is because feminists, starting with Simone de Beauvoir, were only considering the reproductive aspects of the female body as that which makes us different from men, leaving other biological aspects to the side. Evidently the concerns and realities of trans bodies, elderly bodies, or surgically changed bodies are nowhere near this picture of pinning down difference in terms of biological needs. For twentieth-century feminists, the source of female oppression was the fact that women had been historically defined by their bodies. For de Beauvoir, the ontological existence of females is specifically rooted in the need for human reproduction, which confines women to their own sex: a woman is a uterus, an ovary, she is female and that word is enough to define her.2 For this reason de Beauvoir posited female bodies as alienated and opaque—the alienation exacerbated by pregnancy and by the exhausting servitude of, for example, breastfeeding, among many other responsibilities. When women reach menopause, according to de Beauvoir, they become free from the yoke of reproduction, and furthermore can be consistent with themselves, perhaps forming a “third sex.”3 In comparison, a man’s “genital life does not thwart his personal existence.”4 Countering Sigmund Freud’s anathema of a claim that “anatomy is destiny,” de Beauvoir was therefore the first feminist to draw a distinction between species (biology, sex) and society; for her, the species is realized as it exists in a society. A woman’s body is by no means enough to define her, and thus one is not born a woman but becomes a woman. From certain feminist points of view, society’s customs cannot be reduced to biology, because biology cannot completely provide an answer to the question of women’s oppression. This is why the battles of twentieth-century feminisms were, first of all, struggles to free women from the physical constraints of reproduction.

Cocurated by Jimena Acosta Romero and Michelle Millar Fisher.

Path and Pfizer Inc., Sayana Press (API: MedroxyProgesteroneacetate), 2012. Courtesy PATH/Patrick McKern.

Upright Birthing Chair, 2017. Exhibition model designed by Paola Flores (muca-Roma). Photo: Jimena Acosta Romero.

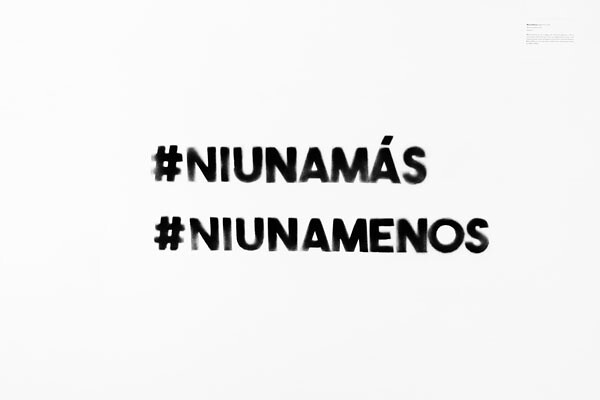

Top: #NiunaMás, México, 1995; aerosol and stencil on wall. Bottom: #NiunaMenos, Argentina, 2015; aerosol and stencil on wall. Photo: Jimena Acosta Romero.

LifeWrap NASG (Non-Pneumatic Anti-Shock Garment), 2016. Duraprene and velcro fastening with jersey cover. Courtesy of Life Wrap NASG.

In this image: Fax (box, single loose tampon, and instructions), early 1930s; Tampax Box, 1936; New Freedom Pads, 1970. Courtesy of the Museum of Menstruation. Photo: Michelle Millar Fisher.

Cocurated by Jimena Acosta Romero and Michelle Millar Fisher.

The issue of the bodily liberation of women is at the center of my dear friend Jimena Acosta’s exhibition “I Will What I Want: Women, Design, and Empowerment,” cocurated with Michelle Millar Fisher.5 You and I went together to see the show, which gathers objects that were designed to alleviate women’s bodily reproductive burdens by enabling them to take control of their own fertility, fluids, and reproductive process: the internal condom, dial pill dispenser, sanitary pads, ruby cup, upright birthing chair, breast pump, baby carrier, gender-neutral toys, etc. It struck us that the exhibition posits design’s complex and contradictory role in gender expression and equality, and the fact that the material world is largely designed by and for men, but consumed also by those who identify as women. “I Will What I Want” is a collection of industrially manufactured objects that have sought to positively shape female experiences and to help women emancipate themselves. At the same time, it underscores how reproductive functions and biological information are both essential elements to women’s (as well as men’s) experiences in the world. The pressing issue of the meaning of the female body as a natural fact is brought up in the juxtaposition between objects designed to alleviate menstruation and photographs by Arvida Byström—which depict women in various everyday situations whose menstruation transpires uncontrolled through their clothes—as well as the viralized image of Kiran Gandhi, who ran the London Marathon in August 2015 menstruating without protection. I think that Byström’s photographs and Gandhi’s gesture radically bring into question considerations of the body as merely cultural and separate from biological facts, and the definition of the “feminist woman” as a female who needs to detach herself from her bodily functions so that she may join the ranks of egalitarian humanity. Perhaps it is necessary to rethink the gender/sex distinction which has been premised, I suspect, on the mind/body separation upon which Western epistemology has been built.

Twenty-six-year-old Kiran Gandhi chose to proudly bleed while on her period during her first run at the London Marathon, 2015.

Following Judith Butler’s reading of de Beauvoir, since women were historically identified with their anatomy, and because this identification served to oppress us, de Beauvoir gave feminists the task of identifying themselves with “consciousness.” This is to say, women’s emancipation meant that enacting transcendental activity would not be restricted by the body. In the Western differentiation between “men” and “women,” the latter, as we have seen, had been defined by corporeality and as “biologically determined,” while the former were conceived as able to transcend their bodies toward “reason,” and to become a meta-consciousness.6 I pondered on the fact that the sex/gender division not only follows the Western mind/body split, but also obeys the feminist call to liberate women from their enslaving bodies so that they can transcend their corporeal status and become “consciousness,” like men. This is why we have insisted on the body as a situation: as the site of cultural interpretation, a material reality defined by its social contexts. And herein lies the paradox laid out by the collection of objects exhibited in “I Will What I Want”: Is emancipatory design truly grounded on immanent bodily needs, or are the object’s interpretations of those needs bound up with the concern of certain feminisms to undo anatomical difference to achieve gender equality? You, my love, have worked in a male-dominated business world. I wonder if you ever felt this need to somehow undo gender difference as a strategy to get respect in that world? Or on the other hand, have you ever felt the need to emphasize that difference?

Printable 3-D jewelry of a vulva and clitoris. It integrates one of the most recent anatomical models of a clitoris, dating from 2009. The rendering portrays the model with a brass surface.

Then I realized that to think about biology as determinant of women’s experience, as it is aligned with the nature/culture dichotomy, is to think about coercion. And it is precisely those objects in “I Will What I Want” that enabled women to enter the productive workforce in the 1970s, by allowing for the possibility of palliating or managing reproductive functions. In the exhibition, this is highlighted in the juxtaposition between “Finding Her” posters produced for the UN by DDB Dubai, and the display of an array of breast pumps (which, as you know well, have always terrified me to the point of never being able to use one). In a way, the encounter of the posters designed in 2017—focusing on three particularly male-dominated industries: politics, science, and technology—to draw attention to the lack of women in the Egyptian workforce, which is only 23 percent female, opposes the assertion that biology is not necessary for women’s politics. For instance, following de Beauvoir, Gale Rubin dissociated the study of gender from the study of sexuality in the 1970s. In her view, biological explanations are unrelated to the political, because sex and sexuality are natural forms preceding social life. She writes: “The body, genitals and capacity for language are necessary components of human sexuality; but they do not determine its content, its experience nor its institutional forms.”7 Sex is understood as: penis, vagina, testicles, estrogen, and they all have nothing to do with politics. Gender is, according to this account, “everything else.” That is, gender is a system of social signification and semiotic formation.

Taking a different stand than that of Rubin, Butler reads de Beauvoir’s axiom that “one is not born a woman, but one becomes a woman” not as a call to alleviate the female reproductive function, but rather as a battle for gender. For Butler, gender is an identity that both precedes the self at birth and that is gradually acquired. But, she continues, while sex is an invariant factual aspect of the body, what concerns feminism is the acculturation of that body. The distinction between sex and gender serves to attribute the value of the social functions of women to biological necessity, and to halt the reference to gendered behavior as “natural” as well. For Butler, all gender is “non-natural,” and in fact, many feminist projects seek to undermine the presumption of a causal or mimetic relation between sex and gender. This is to say that “becoming a woman” is a subjective and cultural interpretation of being female that is completely independent of the ontological condition of “being female.”8 While bodies are “natural,” genders are “constructed.” Likewise, “being female” and “being a woman” are two different kinds of being. Therefore, gender is a process of self-construction that implies the assumption of certain corporal styles and their accompanying meanings. Furthermore, gender is inscribed in the biological body, which is conceived only as a passive medium. In other words, “becoming” a gender is a choice, and also implies acculturation, subjecting oneself to a cultural situation as well as creating one. You know, for Butler, it is not that the body needs to be liberated from its reproductive function, but rather from the oppressive social interpretations of the reproductive body.

But somehow, to be able to construct one’s gender still feels like a trap. Maybe there can be more answers if we rethink the relationship between “me,” “my sex organs,” and the rest of my biological information, or if we incorporate biology into how we think our bodies—aside from them being blank slates in which cultural norms and nonnormative gender meanings can be rejected or reinscribed. I started thinking about this when you began having hormonal fluctuations, and still to this day, doctors have not been able to sort you out because your lab studies have always come out “average.” There is a passage about family and gender in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts—remember that we read it when we first got together?—that brings forth, in part, what I’m trying to get at: that maybe bodies are not empty vessels with biological functions detachable from their cultural functions. Because, although we reappropriate gender and inscribe it on our own bodies on our own terms, and notwithstanding that we have reinvented kinship relations, there is a trap that we always fail to avoid. In this passage, Nelson tells the story of how a friend came over to her house and found a coffee mug that had been given to Nelson by her mother. The mug had a photo of Nelson’s family printed on its side, the family all dressed up to go to the Nutcracker at Christmastime—a ritual that she enjoyed with her mother when she was little, and that she then continued with her own family. After seeing the mug, her friend exclaims, “I have never seen anything so heteronormative in all my life.” But what is heteronormative about the photograph? Nelson ponders:

That my mother made a mug on a bougie service like Snapfish? That we’re clearly participating, or acquiescing into participating, in a long tradition of families being photographed at holiday time in their holiday best? That my mother made me the mug, in part to indicate that she recognizes and accepts my tribe as family? What about my pregnancy—is that inherently heteronormative? Or is it the presumed opposition of queerness and procreation (or, to put a finer edge on it, maternity) more a reactionary embrace of how things have shaken down for queers than the mark of some ontological truth?9

Is it about queer people having children? Is heteronormativity linked to the “female animal”? Although we have learned to exist in our bodies by reconfiguring given gender norms, I too, like Nelson, feel trapped. We thought that emancipation meant that we could dissociate ourselves from our own reproductive functions—or choose it from an array of other gender possibilities. But maybe the problem I am trying to articulate resides in the inferior roles that, on the one hand, have a biological significance in the way that we think of ourselves as “culturally constructed entities,” and on the other, have the status of reproduction in Western neoliberal societies: undermined by capitalism and also by certain feminist battles for liberation from the reproductive function. And as a result, we are undergoing what Nancy Fraser has called a “crisis of care.” She explains that women who give birth still have the pressure of having to nourish and educate children, look after friends and family members, see to the upkeep of homes and communities, and in general sustain connections. These processes of “social reproduction”—affective and material labor without pay—are indispensable for capitalist societies. Without reproductive labor there would be no culture, no economy, no political organization. We would have no food in the fridge or on the table, no clean clothes, and though I am conflicted on this matter, I am grateful that we each have someone to help us with our “domestic labor.”

And yet, reproductive labor has been systematically disregarded and invisibilized; it is neither remunerated nor recognized, and it is still being imposed on women because someone needs to do it, and because it has been proven that a society that systematically undermines social reproduction cannot last for very long. A case in point is the social implosion and spiral of violence that is emerging in Mexican cities like Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, where women have joined the workforce as sweatshop workers. Owing to the lack of social, corporate, or familial networks of support and care for their children, many of them have turned to criminal activities, some as young as teenagers. For Fraser, the crisis of reproduction also manifests globally, and encompasses economic, ecological, and political aspects that intersect and exacerbate one another. The costs of the sustained accumulation of capital in the current system are care and the impoverished ways in which we are sustaining life itself. Just as women have needed to dissociate their bodies from their reproductive function to be free from the yoke of sexual difference, capitalist societies have separated social reproduction from economic production, associating the former with women, considering it low- or unvalued labor. While the “domestic sphere” is obscured and rendered irrelevant, the work of giving birth and socializing children is as central to capitalism as looking after the elderly, maintaining homes, building communities, and sustaining shared meaning.10 And yet, the value of reproduction is rejected by capitalism, but also by certain feminisms as well.

Women, who have joined the productive workforce, are similarly in need of subcontracting family and community care. In this new organization of social reproduction, care has become merchandise for those who can afford it. Leïla Slimani’s novel Chanson douce (2016) addresses the commodity status of reproduction and the tensions its commodification raises between personal life and affective entanglements.11 The premise of Slimani’s Goncourt Prize–winning novel (she is the second Moroccan and the twelfth woman to have won the award) is the murder of two children by their nanny. Slïmani thus paints a primal scene of care exchange value, with anxieties, hypocrisies, and inequalities all arising from the logic of care itself. In our globalized world, privileged women have to pay—sometimes large portions of their salary—for the right to join the ranks of productive labor. As women are considered equal to men in all spheres, we look out for the equal opportunities we deserve in order to realize our talents in the spheres of production. Reproduction, therefore, becomes an uncomfortable residue, an obstacle for advancement in the liberation of women.

The conclusion that I’m drawing from all of this, my love, is that while culture does play a broad role in giving shape to differences among genders, to deny the role of reproduction in society—which is parallel to the denial of the role of biology in our lives, to the extremes of Soylent, Excedrin, and other neoliberal excesses to maximize productivity—has proven to be a dangerous trap that maintains a significant portion of women’s ordeals in darkness. In Gut Feminism, Elizabeth Wilson proposes to incorporate biological information to rethink mental and corporeal states in their relation to gender.12 This is to say, she proposes to consider the body beyond the way it is described by culture or inscribed into cultural contexts, and to consider instead how it is shaped by biology. For instance, if cultural constructivism determines that men behave aggressively not because of testosterone but because of “toxic masculinities,” perhaps Paul B. Preciado’s experiments with testosterone are a much needed empirical and conceptual bridge between biological bodies and their cultural interpretations.13 Or, if cultural constructivism argues that women are more inclined to care for and raise children because they have been conditioned by the heteropatriarchal order, maybe we should consider transsexual people’s need to equate sexual identity with gonad tissue and genitals, or transgender people’s contradiction between gender identity and lived experience, as evidence that the biological, hormonal, and neurological differences that give shape to gender need to be brought to the table. Because of this, I find it terrifying that the root of the sex/gender divide harks back to the modern conception of man as “reason.” Fully dissociated from the body, the ideal condition of “man” translates to the ideal of “woman” as pure consciousness. If we speak of situated knowledges rather than universalizing scientific, Eurocentric, and masculine visions, could we embrace a kind of situated biology that would consider not only two or three sexes, but myriad sexes that could be expressed limitlessly through our bodies? And from what standpoint could we organize a political struggle that would have as its goal a society that would celebrate, support, and value reproduction instead of negating it and undermining it? I know; I always demand too much.

Lauren Berlant, “The Book of Love is long and boring, no one can lift the damn thing,” Berfrois, May 14, 2014 →.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (Vintage, 2012), 41.

De Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 65.

De Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 37.

“I Will What I Want: Women, Design, and Empowerment,” cocurated by Jimena Acosta Romero and Michelle Millar Fisher. Its first venue was the Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries, at the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center (Parsons School of Design / The New School, New York) April 11–23, 2017. It then travelled to the Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Artes (MUCA) Roma, in Mexico City, January 18–May 22, 2018.

Judith Butler, “Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex,” Yale French Studies 72 (1986): 35–49.

Gale Rubin, “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex,” in Toward an Anthropology of Women, ed. Rayna Reiter (Monthly Review Press, 1975), 162.

Butler, “Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex.”

Nelson, The Argonauts, 12–13.

Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care,” New Left Review 100 (July–August 2016) →.

Leila Slïmani, Chanson douce (Gallimard, 2016).

Elizabeth Wilson, Gut Feminism (Duke University Press, 2015).

Beatriz Preciado (Paul B. Preciado), Testo Junkie: Sexo, drogas y biopolítica (Espasa, 2008).

Category

Subject

To Lizzy Cancino and lovingly to my friend Ruth Ovseyevitz whom I am infinitely grateful to for helping out with my reproductive tasks so I could finish this text.