Body of Work

In glassblowing, you take a metal pipe about four-and-a-half feet long, stick it into a furnace of molten glass, and spool a glob of glass onto the end. The glass comes out of the furnace at two thousand degrees, a glowing, molten mass, and you must constantly rotate the pipe so it doesn’t flop over and collapse onto itself. A steady spin helps to keep its center. The glass cools at a rate of fifty degrees per second, its behavior changing radically with each moment. It is never cool enough to touch with your bare hands so you shape the glass with other tools and movements. You sit at a bench and rest the glass end of the pipe on a narrow rail, which is the only thing keeping it from falling into your lap, and take what is called a rag, but which is really a thick pad of newspaper soaked in water, and you cradle the glass like it’s a newborn’s skull, rotating it constantly and shaping it in your hand. The hot glass on the wet paper creates a burst of steam and the glass rides the vapor as you turn it. The newspaper chars, burning slightly. You’re almost touching the glass—there’s less than half an inch of newspaper between your hand and it—but you’re not. You can’t touch it yet you feel it through its weight shifting at the end of the pipe, through the changes in density, through the lubrication of the steam.

Studies have shown that the objects we hold become neurologically incorporated into our perception of our body—especially if we use them as tools that extend our body’s capacity. Monkeys who learned to use a rake to obtain objects showed activity in the areas of the brain that register touch on the hand as well as objects appearing near the hand, suggesting that the brain considered the rake to be part of the hand.1 Other tests with human subjects showed that though a tool was perceived as part of the hand, the objects the tool touched were not. The implication was that direct contact with the skin was crucial. But this is not what I experience with glassblowing; there, my sense is that the glass is an extension of my own tissue.

As a dancemaker, it’s evident to me how much glassblowing comes down to choreography and kinesthetic empathy. When you have your chunk of glass in the furnace or glory hole (more on that terminology later), there’s a way you can sense—not just see, but sense—how the glass is changing and anticipate when to take it out. It’s similar to the way we intuitively know how far a rubber band can stretch before it will break, how big a bubble we can blow before it pops on our face. I’ve been trying to find the term for having empathy with the physical properties of an inanimate material—how we experience our own body through its relationship to other things, how we exhibit a capacity for grafting with materials that we should reject.

“Somatic resonance” almost gets at it. Here, “somatic” and “resonance” are dance terms, often associated with movement pioneers like Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, the developer of Body-Mind Centering®, who says that “when we touch someone, they touch us equally.”2 The boundaries of our experienced body can change freely and extend to other people but also to objects. Or as cognitive neuroscientists Patrick Haggard and Mathew Longo write in Scientific American, “While we think of our body as a fixed feature of our lives, the brain displays a surprising ability to accept as part of ‘me’ whatever I happen to be touching and using at any given time.”3

The brain anticipates touch as a two-way street. We sense not just what other objects feel like but also what it would feel like to be touched by them. The hand that touches also receives touch and this simultaneity is one of our very first experiences of the tactile world. Bainbridge Cohen describes the development of this faculty where perception occurs in the cellular, etheric, and immediately physical realms:

We first experience these senses in utero. As we move in utero, our skin is stimulated by the amniotic fluid, the uterine wall and by one part of our body touching another. Thus we discover touch and movement in synchrony. Movement occurs at two levels, movement of our cells within the boundaries of the skin and movement of the body through space. Touch also occurs at two levels, cellularly and contact of our skin from the outside.4

Touch is entwined and flows in both directions. Thinking of touch not as an on/off switch (you’re either touching something or you’re not) but as an arcing energy through space that in fact encompasses that space and charges it with the anticipation of touch, makes touch a continuous, liquid action.

Rheology is the study of the deformation or flow of matter—when a substance gains viscosity or changes from a liquid to a solid. It applies to many substances, including glass, but also mud, lava, and blood. My mother is a retired medical technician. When I was trying to find a term for empathy with the cellular changes of a material, she wrote to me:

There’s a lab test called “pro time” [short for “prothrombin”], which measures the coagulability of blood. You pipette a small amount of calcium solution into a small tube of plasma, start a stop watch and tilt this liquid mixture back and forth until it becomes a clot. Normally this happens in 13 sec. When is it liquid and when is it a clot? After much practice, you can intuit the millisecond of change, even though you can’t actually see a change, you just know it is coming. The term for this moment is “end point.”

This is a wonderfully macabre example, since it deals with the body recognizing the rheology of its own substance—blood; the body watching and intuiting a piece of itself. The body out of body.

Heather Kravas, dead, disappears, 2016. Documentation of a dance performance Photo: Tricia Keightley

Crunchy On the Outside, Rubbery On the Inside

Intimacy travels through the objects we touch, expanding the circuit of consciousness to include the conducting materials as well.

Many years ago, my former partner and I were in Hawaii, staying at a little house on the water. On our second day, we discovered a gigantic centipede in the bathroom. It was about eight inches long, and horrifically scary and disgusting and fascinating. We decided we had to kill it. We looked around for a weapon and found a broom, the kind with an angled, bristly straw head. The bristles were firm enough that they might stun or perhaps brain damage the centipede, or maybe cause it organ failure. Not necessarily dismember it, which would be messy and unpleasant. It was only in retrospect that I realized I’d contemplated any of this in those few seconds and that I’d never before considered just how an insect dies biologically after a human attacks it. I crept back into the bathroom, took up a position, and jabbed the centipede with the broom, not accurately enough to maim it but enough to make contact and instantly feel the rubbery, buoyant integrity of the centipede’s body—a steel rod wrapped in a gummy worm covered with a hard candy coating—translate all the way up the broom; through the bristles, up the wooden handle, all the way to the flesh of my right hand, gripped around the end of the broom as a final shock absorber for this horrible sensation.

I don’t know if centipedes are smart. Having attacked it and missed, I didn’t know what to expect. Plus, I was gagging from the revolting feel of its body through the broom. Which was perhaps its evolutionary strategy: to simply be disgusting. The centipede—ran? scurried?—rematerialized in a flash, up underneath the bathroom counter, which was open underneath to accommodate a chair. I dropped into a squat, awkwardly jabbing the broom up into the corner where the counter met the wall and where the centipede had lodged itself, flattening and creeping sideways into the crack with every hit of the broom. The broom’s long handle meant I didn’t have to get too close but it also made it hard to maneuver from a squat. Each blow had to have impact. Actual and figurative.

The first few strikes I landed again bounced back at me with that thick, sickening softness. The more I stabbed the broom, the more the centipede wiggled into the gap, and soon the only palpable message back from the end of the broom was the texture of wall, wall, wall. The centipede had survived but was nowhere in sight. We grabbed our guidebook (this was before smartphones) and discovered that the Scolopendra subspinipes is a poisonous species of centipede. Their bites have been compared to the pain of childbirth and kidney stones (if the kidney stones were also on fire). I prayed that I’d maimed maybe forty of its one hundred legs so it wouldn’t be able to crawl up into my bed while I slept but I knew from the sensations I’d gotten via the broom that I’d done nothing more than scare it. We never saw the centipede again but I’ve lived with the body-to-body intimacy of our encounter as mediated through that broom for these many years. In fact, holding a broom so that its bristles just graze the floor is enough to bring it all back. The centipede is always at the end of that tool.

Photo: Jessica Cressey

The Tool That Shapes the Hand

We don’t have to have something against our skin to feel it. Feeling something feeling something is still feeling something. But sometimes an inanimate object can amplify to us the most familiar object of all—another body.

The book Strange Piece of Paradise is a memoir by Terri Jentz that recounts her nearly fifteen-year search for the unidentified man who tried to murder her. She’d been nineteen, on a cross-country bike trip with her college roommate, and only a few days into their trip, while they were camping in rural Oregon, a man drove his pickup truck up over the curb, onto the grass, and over the tent in which they lay sleeping. He backed up, got out, and started attacking them with an ax.

Jentz is tangled up in the tent and thrashing from side to side as he attacks her. Her fingers grab at what’s hitting her and she feels the curve of cool metal. He stops attacking her for a moment and she opens her eyes to find him standing above her, straddling her and gripping the ax with both hands in a pose of perfect symmetry. He lowers the ax very slowly in what she later comes to understand is a measuring of the chop he is about to deliver. As she writes in the book:

My eyes watch as [the ax] descends to a point just above my chest and pauses, I cup my hands over my heart, clasp the blade, and from somewhere in my body summon a voice. Firm, with a touch of politeness.

“Please leave us alone,” I say. “Take anything. Just leave us alone.”

He says nothing.

I can see quite clearly, inches in front of my eyes, both hands just over my heart, folded like a prayer around the blade.

Then gently, ever so gently, he lifts the hatchet from my grasp, steps over me, and walks away.5

By then, he’d already cut through the muscles in her arm, made lace of the fine skin on her scalp, slashed her fleshy palm, broken her nose, and sliced through one of the bones in her forearm. He’d also bashed a hole in her roommate’s skull. He’d had plenty of tactile information sent back through the metal blade and wooden handle of the ax. Bone, flesh, muscle. But when she’d sheathed the blade with her hands, he’d stopped. This was a different kind of touch; if the ax was an extension of his hand, she’d enfolded it in her own.

Leslie Van Houten, one of the women convicted of killing on behalf of Charles Manson, described feeling a similar “exchange” with her victim, Rosemary LaBianca, at the moment of the murder. There is some dispute over whether Van Houten technically killed LaBianca (it’s generally accepted that she stabbed her only after she was already dead) but in a 1987 interview, Van Houten acknowledged the enormity of the relationship she felt by “being with her, being next to her,” by holding her down when she died. For Van Houten, this was a tragic supernatural connection that triggered a cascade of guilt and responsibility for what she had done. Though she was in the opposite situation than Jentz—attacking rather than being attacked—both events involved weapons that required close physical contact. A gun allows distance; an ax, a knife require touching. Holding.

This is inescapable confrontation with our shared human biology—our skeletons, organs, soft tissue, skin are mostly organized the same. We’re made up of the same stuff. If I stab you, I must instantly discover what it’s like to be stabbed. And vice versa. We know what we do to each other. When we touch someone, they touch us equally.

Mirror neurons may be at work here; the neurons that fire in my brain when I observe you doing something are the same neurons that fire when I do that very thing myself. It’s as if watching you do it means I’m doing it. Studies have shown that the brain responds to images of touch in the same way it responds to touch itself; the same areas of the somatosensory cortex fire when subjects are touched on the leg as when they see images of others being touched in the same spot.6 Those same regions of the brain are activated when you watch someone dance.7 Mirror neurons are also thought to be responsible for how I know what you’re going to do before you do it. They help me know from the way you stand up if you’re just stretching your legs or preparing to leave the room.

But spending a few decades as a dancer helps, too.

Photo:@josephichiban

The Out-of-Body You

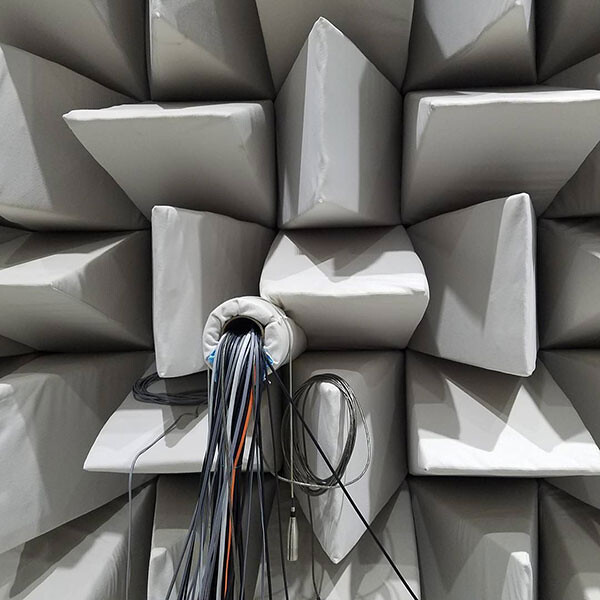

There is a place in Minneapolis called Orfield Laboratories. It conducts research in acoustics, vibration, and lighting. They can measure the imperceptible working tones your phone is emitting right now. Before it became Orfield Labs, the building used to be a recording studio known as Sound 80, where Bob Dylan made Blood on the Tracks, Prince recorded his early demos, and Lipps Inc. recorded “Funkytown.” But if you’ve heard of Orfield Labs it’s because they have an anechoic chamber that has twice been named the quietest place on earth by The Guinness Book of World Records. It absorbs 99.9 percent of sound. It’s a room without sound, until you put something in it. A few years ago, I went on a tour of the lab led by Steve Orfield himself. He took us into the anechoic chamber, which is a small room, about ten-by-ten feet, with three-foot-thick acoustic foam wedges attached to walls made of insulated steel and a foot of concrete. The ceiling, walls, and floor, which consists of a suspended wire grid, have no direct contact with the structural walls of the building, so as to minimize vibration. Essentially, the chamber feels like a free-floating, soft-walled dungeon. The density of the air is different. You feel it in your ears when you walk in. It’s like a change in air pressure, but it isn’t exactly. It’s more of a deadness, a thickening. There are stories that anechoic chambers will make you crazy after less than a few hours. The only sounds you can hear are those of your own body. Your heartbeat, sure, but also eventually the sound of your blood coursing through your ears, the smack of your upper eyelids against your lower. Supposedly, no one has stayed in Orfield’s anechoic chamber for more than forty-five minutes.

So when Steve offered to close the door, turn out the lights, and leave us there in the sonically dead pitch dark, we said yes. There were about eight of us. We got ourselves situated on the floor and then he shut the door and cut the light. I sat cross-legged in the dark, waiting. After a bit, I realized I hadn’t fully shut down my phone, which was in my back pocket, so I twisted around to my right side to turn it off and suddenly, it was as if I had been flung into darkness. Though I’d already been sitting in complete darkness for at least thirty seconds, I hadn’t yet changed my physical position, which made my mind continue to perceive light where there wasn’t any. I thought I could see the rest of the group, the sitting position of the person across from me, their proximity. But I couldn’t actually see any of that because the lights were off. Without light and reflected sound, my brain’s perception had been anchored only by my body’s position, and as soon as I’d changed that, the connections between body, brain, light, and dark were ripped away. Suddenly I was reeling. My body felt spongy and disoriented. I no longer had a sense of the size of the room or where anyone was within it, I didn’t know where the walls were, or the distance between my elbow and hip, my chin and the floor. I gave myself over to this dizzying absence of location. I listened for my heartbeat, terrified I would hear it—for the flow of blood in my throat, my ears, terrified I would hear it. Could I stand an hour in this room, hearing my mortality bang around in my chest? I had only gotten started on the task of taking myself apart and giving myself away when a few minutes later, Steve opened the door.

Recently, I read about an experiment that explored this type of sensation. If you hold your hand out in front of you in a darkened room and see it illuminated by a bright flash, an afterimage of your hand remains. Like a retinal burn. If you then drop your hand, the proprioceptive part of your brain feels your hand move, but the visual part of your brain still sees the afterimage and your brain can’t integrate the sensations—they’re in conflict with one another. So to resolve this, the brain dissolves the afterimage. You end up seeing a fading or a crumbling. It’s called a ghost hand. Sometimes I think of dances as akin to this ghost hand—when you make a dance, you’re making a thing that is of you, from you, but not ultimately you. It’s the out-of-body you born of your body, and you make it and then it’s gone but it also stays. It remains but degrades. It adheres and disappears.

_(Art.IWM_ART_LD_2851)WEB.jpg,1600)

_(Art.IWM_ART_LD_2851)WEB.jpg,1200)

Mervyn Peake, Glass-blowers “Gathering” from the Furnace, 1943. Watercolour on paper 50.8 x 68.5 cm. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Imperial War Museum

Superfeelers and Blowhards

Dance requires being adaptable, watchful, and highly in-tune with others. You learn how to observe someone or something and re-embody it. Which means on some level, you understand yourself to be what you are watching. This is a dialogue based in its own runic language. Dancers have an exceptional ability to intuit, interpret, and anticipate others and to work together without needing a lot of discussion. They’re good at committing to their own task while working towards the group whole, the common good. It is the deep intelligence of this intuitive, body-based social solidarity that makes me believe dancers should run the UN (should the UN still exist as you’re reading this).

Dancers can quickly deconstruct the essence of what and who they are watching, separate out the important pieces and reactualize them. This is not imitation but embodiment, animation, (re)creation. I have a friend who can do a pitch-perfect reenactment of Charlize Theron as Aileen Wournos rollerskating in the movie Monster. She can do it having seen the movie only once fourteen years ago. And she can do it without needing the rollerskates. I wouldn’t know how to describe “Charlize Theron as Aileen Wournos on rollerskates” but she can simply be it—and thus distill the entire emotional and visual life of the character (and the entire film) into about four seconds. A lot of dancers I know can do this. They can capture something you can’t explain or didn’t realize you’d observed and just show it to you. Suddenly, the person they’re embodying is alive within them—they are both themselves and someone else, indistinguishable yet distinct from each other—and when they stop, that other person is gone, it crumbles. It is remarkable to witness and if you’ve never seen it, you need to spend more time with dancers.

Maybe dancers have more highly developed mirror neurons but I think they sense with another sense. Dancemaker Lisa Nelson codified this with her Tuning Scores, which embed “the practice of observation into the practice of action”:8

First, it is physical—tuning is an action. It moves my body, my senses, and my attention. It’s also sensual—I can feel it happening in my body. It’s relational—it’s the way I connect with things. And it’s compositional—it puts things in order.9

Studies by Karen Kohn Bradley and Dr. Jose Contreras-Vidal show that dancers store the logistics of the choreography in the cerebellum, opening up the frontal lobe for interpretation, invention, and problem-solving.10 It’s a total intelligence, and as Bonne Bainbridge Cohen says, “The mind is like the wind and the body is like the sand; if you want to know how the wind is blowing, you can look at the sand.”11

Arts writers Andy Horwitz, Nina Horisaki-Christens, Claire Bishop, Aaron Mattocks, and others have observed that the visual art world of late is interested in performance that looks untrained, which it equates with authenticity.12 But many in the visual art world remain ignorant of the history of dance and contemporary theater, which have both already spent generations thoroughly exploring the idea of “untrained.” Dance has exhaustively excavated the pedestrian, the amateur, the raw, and the unpolished, most famously through the Judson Dance Theater’s work in the early 1960s. If anything, dance is in a retrograde right now; revisiting formalism and molding it into experimental structures. Dance has already annealed the Judson and post-Judson legacy into the current moment. Dance understands that authentic experience isn’t married to form. It doesn’t have to look raw to be real. A lot of visual art venues don’t think they’re presenting “dance” and a lot of visual artists don’t think they’re incorporating “dance” into their work perhaps because they think dance is Martha Graham not Richard Move, still stuck in its original amber rather than reimagined by a succession of radical new nows. They often don’t know what dance has already innovated in terms of human presence in the last fifty years and think anyone can incorporate a live person into their work, call it “performance,” and have it be interesting. I’m not saying that dance, performance art, theater, and performance are interchangeable or all the same thing. But by not knowing how they’re not the same thing, one essentially says they are.

Dance sometimes emphasizes training and technique (depending on the kind of dance we’re talking about), but it’s always interested in experience—both the verb and the noun. It doesn’t matter what kind of dance you’re doing or were trained in or if you were trained at all. In dance, your lifetime of experience, your hours in the studio and out, onstage and off, is considered invaluable; it’s both the content and the tool of the art. Honing consciousness around it is dance’s craft. Being able to feel at ease while people watch you have that consciousness is a skill that takes years to develop. This cultivated authority is what I would define as technique regardless of what the dancing or the performance looks like. Experience is both the objective and the object.

In the downtown world of yore (meaning the 1980s to the early 2000s), we used to use the words dancer and choreographer largely interchangeably. I don’t know if it was because the distinctions didn’t matter or that the assumption was that you did both (which is always true in dance but since performed improvisation was so prevalent in those days, you truly were doing both in the same moment). I don’t recall when the distinctions started to matter so much and why. Was it because funders asked that we delineate ourselves and so we did? Or maybe hierarchy became important again as the economy improved—a choreographer is seen to hold more power than their dancers and is credited as the mind of dance, where dancers are viewed as the body of dance. Among all the familiar misogynies that privilege male choreographers over female ones, despite men being a distinct minority in the field, there is that one—the powerful choreographer is the brain, the subservient dancer is the body. Male choreographers are seen as gods, female choreographers are seen as … difficult. (This is yet one more frontier where those who identify as nonbinary do us all a great service.)

One of the psychological hazards of dance is that you are the in-person, live representation of your art; you are both the method and the very existence of it. So when people judge or critique your art, they are also judging and critiquing your very physical existence in addition to your artistic ideas. A painter doesn’t have to stand next to their painting during gallery hours and absorb every comment and reaction to their work (although maybe someone has already done that piece). Performance that does occur in visual art settings is generally regarded as not happening in real-time; gallery-goers have been trained to prize the object-ness over the live-ness and this is reflected in how they navigate the room, the art, each other, and notions of “audience.” At the institutional level, this has been reflected in the failure to provide workable conditions for the performers, who are more than sculptural materials and require things like bathrooms, temperature-control, breaks, a livable wage, and occasionally even physical protection.13

Much discourse around visual art stands at a similar remove from its maker. The visual art world’s notorious, absurdist “artspeak” is composed to sound as though it’s deepening specificity when it in fact diffuses it. Narrativisation. Potentiality. Boundaried. When applied to dance, it could not be less descriptive if it were trying to be (which suggests maybe it is). It’s downright depressionism. What we call “presenters” in the dance world are called “curators” in the visual art world and when you apply that word to an art form that consists of living human beings, we are already off to a disconcerting start. Designed to assess you as someone who does or does not get art, this is language as status. It locates you in a class position. By speaking it, you elevate yourself to that world. The expression “an economy” of words takes on new meaning when the art world talks about dance.

But code switching is part of dancing—you learn how to speak other people’s physical and creative language—so dancers, with their expert cerebral synchronization, can keep up with the jargon. Dance has for so long been the poor cousin that it’s eager to prove its legitimacy in the moneyed art world and receive its imprimatur. Well, maybe not “eager”—the dance world has a very healthy skepticism of the visual art world at this point. But there remains allure with how museums and galleries signify status, intellectualism, and the authority of images, as well as the security associated with buying and selling, commodifying even the intangible. It’s possible that the visual art world is better at figuring out how to market and monetize the abstract, and perhaps that’s part of their interest in dance. If Performance Art was a challenge, Dance is rough trade. And the art world does love to be hoodwinked and humiliated, peed on and flogged. But it’s a classic case of topping from the bottom; the relinquishment of power is an illusion. The visual art world hasn’t surrendered its language. There is no safe word.

Photo: Jessica Cressey

The Happy Ending

Glassblowing, on the other hand, holds no illusion of role-playing in its language. The jargon is filthy and wonderful and wonderfully homoerotic. In addition to putting your pipe in the glory hole, you paddle someone’s bottom and you blow them after they jack. One day my instructor said, “When you come out of the glory hole you’ll blow, jack, blow, jack.” I expressed silent gratitude that none of my classmates were named Jack. One beginners’ exercise is described to students as making caterpillars or snowmen, but glassblowing instructors across the country have told me that to each other they refer to it as making anal beads or butt plugs. Other terms include necking, pegging, flashing, and wetting off. Glassblowing is notoriously macho and sexist. There’s a lot of swagger—they’re playing with fire after all. The arrogance is such a point of pride that there’s even a term for it: glassholes. As in dance, there are a lot of women in the field but the most famous and successful glass artists tend to be straight men. While glassblowing’s use of the term “glory hole” predates the slang usage by over one hundred years, I wondered about all these macho dudes working with this homoerotic language for so long—if the swagger itself was overcompensation for having to ask someone to blow you while you jack after coming out of the glory hole.

It’s interesting that glass, a male-dominated field, has continued to embrace its homo (i.e. emasculating, i.e., feminized) language but dance, a female-dominated form, has capitulated, molded itself to the tool through its innate skillset. Dance’s recent adoption of the word “performative” is a symptom of this failure to assert its own unique language. “Performative” is actually a linguistics term referring to statements that function as transactions; the saying of the thing makes the thing happen. The most common example is when a judge says, “I hereby sentence you to twenty-five years.” The uttered sentence effects the legal sentencing; it makes it so. Or when someone says, “I promise”: saying “I promise” performs the act of promising. But lately when dance people say “performative,” they’re using it to say something is consciously acted-out or “performance-like” when they could just say what we already know it to be—a performance. The word “performative” is meant to get at something finite and consummated but dance is unspooling and unfixed. Dance is working on multiple simultaneous levels—the realized and the imagined, the conjured and the never been, the here, the not here, the recently gone. The actual hand and the ghost hand.

At first, I thought “performative” was coined by dance people in order to sound like museum people. But then I realized that the art world’s misuse of this term predates the dance world’s. Which made way more sense but also bummed me out even further. Why would dancemakers do this to ourselves? Why would we let museums rename what it is we already do? And why would we ourselves then use that language to describe what we have already been doing all these years?

I long to see the dance world assert its language as part of its commodity. If you want to present dance, you need to know how to talk in dance’s existing language. It serves the form just fine because it is of the form. Dance doesn’t want to talk about itself from the remove of class or body. Dance wants to be hot in the center of its own glory hole—though it will happily pee on the museum steps for the right price.

Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen writes,

Though [in Body-Mind Centering®] we use the Western anatomical terminology and mapping, we are adding meaning to these terms through our experience. When we are talking about blood or lymph or any physical substances, we are not only talking about substances but about states of consciousness and processes inherent within them. We are relating our experiences to these maps, but the maps are not the experience.14

The molten glass, the metal pipe, the bristles on the broom, the coagulating blood, the perception of the hand, the body in a dark and soundless room are avenues for finding another language, from which dance, which is its own language, and its own art object, is born. Performances are living things, melting, fading, bleeding right next to you; so shouldn’t the language also? Its logic is rheologic; so why shouldn’t its language stay molten? What would this mean in real terms? I mean in real “terms”? I think about the “pro time” test and how the moment that matters is the one right before the blood stops moving and starts clotting. The end point. The moment when you sense that the thing is just about to change form and become static. That you see it coming and you use your words.

Patrick Haggard and Matthew R. Longo, “You Are What You Touch: How Tool Use Changes the Brain’s Representations of the Body,” Scientific American, September 7, 2010 →.

Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®,” bodymindcentering.com →.

Patrick Haggard and Matthew R. Longo, “You Are What You Touch: How Tool Use Changes the Brain’s Representations of the Body,” Scientific American, September 7, 2010 →.

Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, “Touch and Movement,” June 19, 2012, bodymindcentering.com →.

Terri Jentz, Strange Piece of Paradise (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 74.

Christian Keysers et al., “A Touching Sight: SII/PV Activation during the Observation and Experience of Touch,” Neuron 42, no. 2 (April 2004), 335–46 →.

Corinna Jola, “Do You Feel the Same Way Too?,” in Touching and Being Touched: Kinesthesia and Empathy in Dance and Movement, eds. Gabriele Brandstetter, Gerko Egert, and Sabine Zubarik (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013).

Lisa Nelson, “Lisa Nelson: How Do You Make Dance?”, mnartists.org, November 24, 2014 →.

Lisa Nelson, “Before Your Eyes,” Vu du Corps: Lisa Nelson, Mouvement et Perception, Nouvelles de Danse #48-49, Brussels, Belgium, 2001 →.

Karen Carlo Ruhren, “Are Dancers’ Brains Wired Differently?,” Dance Magazine, August 7, 2017→.

Bainbridge Cohen, “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®.”

Andy Horwitz, “Visual Art Performance vs. Contemporary Performance,” Culturebot, November 25, 2011 →. Nina Horisaki-Christens, “Performing Between Action and Script,” Post, October 28, 2011 →. Claire Bishop, “Unhappy Day in the Art World?: De-skilling Theater, Re-skilling Performance,” Brooklyn Rail, December 10, 2011 →. Aaron Mattocks, “Performance at the Beginning of the 21st Century,” The Performance Club, October 2012 →.

Bainbridge Cohen, “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®.”

A version of this essay was first presented in lecture form as part of Half Straddle’s Here I Go, pt 2 of You, March 2017, The Kitchen, NYC.