1.

I found myself collecting all the little fascisms I could. Isidore Heath Hitler is some guy from New Jersey who recently changed his name to Hitler—the initials stand for “I hail Hitler.”

He had also named his son Adolf Hitler. In 2008, Hitler tried to get a birthday cake with his young son’s name on it, but the cake writer at ShopRite refused. A Walmart in Pennsylvania obliged. A year later, the state took his kids away, citing abuse and neglect by Hitler and his wife Deborah Campbell. During an appeal hearing to get back the children, who are all named after Third Reich characters and white nationalist groups, Hitler was told he needed to seek psychological counseling, but he said he wouldn’t because his psychologist was Jewish.

Denying custody, the court citied unspecified “physical and psychological disabilities,” including the fact that the parents themselves were victims of childhood abuse.

I read about the story on major news outlets and local New Jersey websites. My eyes hungrily scanned the paragraphs, which were interspersed with ads oddly related to my email correspondence. The macabre humor of it was titillating at first, but when I think about it now, a guilty sorrow washes over me, a pity for Hitler, but mostly for those who must suffer their relations. Then comes vermilion anger.

Today politics seems fully pathologized: Adhere to the status quo? Desire radical change? Reignite an old order? Healthy politics don’t exist. Everyone is sick, but especially “me.”

2.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is a labyrinthine, sloping field of stelae. Arranged in an elegant, softly undulating grid, they don’t seem very tall from outside the memorial, but as you descend within, an unsettling quiet fills the air. The rectangular stones are clean and simple, and start to grow taller and taller. Everyone who enters is quickly set along their own path. Visitors cut corners in mischievous delight or solemn repose. Everywhere you look—despite all the possible turns one could take—it’s a straight line. Peter Eisenman said his design is all about the “enormity of the banal,” and from the outside, the memorial seems logical, systematic, punctilious. But as you move through it, your confusion deepens, and we become strangers. Is this what we call history?

3.

There’s a Yiddish saying that goes Abi gezunt—dos leben ken men zikh alain nemen. It translates to “Stay healthy, because you can kill yourself later.”

Imagine what Holocaust memorials might look like in a thousand years: comprehensive VR re-creations of the camps, massive museum complexes of excruciating scale and detail, algorithmic factories for sorrow. Or will they exist at all? “Nothing insures a poem against its death,” Derrida remarks on Celan, “because its archive can always be burned in crematory ovens or in house fires, or because, without being burned, it is simply forgotten, or not interpreted or permitted to slip into lethargy. Forgetting is always a possibility.”1

Nothing guarantees remembrance: not the archive, not the internet, not the much-touted “moral arc of history,” nothing. Falsities can be memorialized into fact and violence can be valorized as beauty. As the affective economy booms and busts, the tempo of memory slows its loop. Then it accelerates. Museums and memorials are factories for memory, articulating the act of remembering as a discrete division of labor. Walk these halls, see these artifacts and documents, stare at these statues in public squares, expend your energy in thinking and feeling, and you will have done the work of remembering. Is this the future of labor? Collecting up our affective capacity, purely for the purpose of fixing and circulating social-historical capital? Or will it be enough, one day, to just walk the earth remembering? The entire planet a memorial, a museum, a place to think and feel?

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, 2010. Photo: Hindrik Sijens/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

4.

My Great-Uncle Morty, a short and portly man with an angular, hooked nose, died a couple years ago. He was found at his desk, slightly slumped over. He was in the middle of a game of solitaire. Morty, my mom’s uncle, was the one who told the stories about the family dying in Poland. My whole life I was told that Uncle Morty’s dad was captured by the Russians during World War II and sent to a labor camp in Siberia. When he returned home to Poland, all seven family members were gone. I grew up with this knowledge but never knew the specifics, only that the family was Polish—no specific names, cities, or camps were ever provided. As I’ve attempted to sketch the intergenerational trauma, I’ve found that family, like history, includes an accumulation of silences. It is a palace of unsaids, lingering with hushes, everyone hurtling through it and uncertain how they got there, moving from pain to ecstasy, from boredom to purpose.

5.

It was a beautiful day in 2013 when I went to Sachsenhausen, the concentration camp in Orianenburg. I’d never visited a camp before. I walked the perimeter toward the entrance, the sky was clear and blue and the air was cool and brisk. The trees were lush, and there it was: the architecture passed through me, shifting its weight in my brain and body. I felt doubly a tourist. The place had known me forever, yet I had never been. All my life the familial fact of the Holocaust had swirled around my mind, impinged upon me, and now I came upon it, the near-terminus of an entire people, “my” people, the spring of my identity, the modern font of contemporary subjectivity, ground zero for both the dominant moral paradigm and my othered self. Everyone at some point feels like an other—detached and disassociated and delirious—but not everyone knows this level of estrangement, the type that connects you to yourself while also demanding your total extermination.

As I walked around Sachsenhausen, I saw exactly what I thought I would see, and yet I saw something precisely different. I felt the perfectly uncanny, a “class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar,” as Freud defined it.2 Seeing the exhibits that accompanied the Appellplatz where roll call took place, the bunkers that housed the imprisoned, and “Station Z” toward the back of the triangular camp, where the bodies were incinerated—I still longed for the other camp, the camp where my own family perished. I felt I had ended up at the wrong exhibit, then felt deeply ashamed for feeling that way.

Exhausted, I went to the café on the grounds of the concentration camp and ordered a mozzarella and basil sandwich. For Agamben, the camp, as a model, is not “a historical fact and anomaly belonging to the past,” but rather “the hidden matrix and nomos of the political space in which we are still living.”3 The famous inscription Arbeit macht frei at the entrance—work sets you free—is the kind of total cliché that seems entirely unvanquished since Luther, its five-hundred-year reign of terror continuing through totalitarianism and into neoliberalism. And this sandwich was the condition of possibility for completing this labor—the labor of memory, the labor of trauma—a biological necessity for witnessing the darkness of a forsaken world. The pale, humorless café attendant handed me the sandwich, and I handed him my euros. I scarfed it down as I walked away from the camp back toward the train, and I’m not exaggerating or joking when I say that it was the most delicious sandwich I have ever eaten. And I had earned it: it was a political and spiritual sacrament, a bizarre relief, my body’s automated recognition to never take anything for granted.

6.

What is a Jew? As Primo Levi once said, “Everybody is somebody’s Jew.” For even more perplexing insight, we can look to Isaac Deutscher, the Polish writer who rejected his orthodox upbringing to become a Marxist historian, a biographer of Trotsky and Stalin:

I remember that when as a child I read the Midrash I came across a story and a description of a scene which gripped my imagination. It was the story of Rabbi Meir, the great saint, sage, and the pillar of Mosaic orthodoxy and co-author of the Mishna, who took lessons in theology from a heretic Elisha ben Abiyuh, nicknamed Akher (The Stranger). Once on a Sabbath, Rabbi Meir went out on a trip with his teacher, and as usual they became engaged in deep argument. The heretic was riding a donkey, and Rabbi Meir, as he could not ride on a Sabbath, walked by his side and listened so intently to the words of wisdom falling from heretical lips, that he failed to notice that he and his teacher had reached the ritual boundary which Jews were not allowed to cross on a Sabbath. At that moment the great heretic turned to his pupil and said: “Look, we have reached the boundary—we must part now: you must not accompany me any further—go back!” Rabbi Meir went back to the Jewish community while the heretic rode on—beyond the boundaries of Jewry.4

Deutscher fits the non-Jew—the one who rejects his Judaic structure and stricture—into a long line of Jews, paradoxically reinforcing his Jewishness. The wise Jew is heretical, nomadic, one who chooses exile, one who willingly crosses the boundaries of territory and thought. The notion of constant travel is essential to the question of what makes a Jew.

The legend of the wandering Jew, which has its roots in several independently existing racist myths, goes like this: the Jew, after mocking Christ as he hung from the cross, was cursed to meander the earth for all eternity, hiding and foraging in various farmlands, always on the move.

But is this much worse than terrestrial stuckness? Mobility is a means of escape, a cloak for tunneling, a way of doing the eternal work of moving beyond trauma. In the twentieth century, nationalism begat nationalism, creating an ever expanding territorializing circuit that hardened identities, pitted people against people.

In the face of the Holocaust, Zionists found hope and relief in the state apparatus and its administration of land. They, and nationalists of every stripe, believe they’ve found the ideological antidote to the curse of upheaval and uncertainty: an occupational therapy of power as treatment for trauma. A counter-nationalism, a wage of apartheid.

In 2005, the Israeli government forcibly removed eight thousand colonists who were illegally settling in the Gaza Strip. As Ilan Pappé noted,

In a desperate attempt to thwart the government’s action, the settlers’ crusade adopted an insignia meant to link the pullout with the Holocaust: yellow stars of David and tattooed numbers on the arm. During the actual removal, many of the settlers reenacted scenes they had seen in Holocaust films or museums: parents and children raising their hands, crying and shouting on the way to the luxury buses that whisked them off to Israel. Soldiers and police were cursed as Nazis, and senior army officers were likened to Hitler.5

The settlers have mistaken the disease for the cure. They’ve bought into the bullshit, the idea that Jews’ displacement and travel was only a curse that would bring pain and suffering, that wandering was sad or bad or somehow lesser-than. The truth is that wandering is a strategy, a necessary fixture of peace: it teaches humility, the sharing of space, the circulation of concepts and experiences. Not for nothing does the Greek word for theory, Theôria, mean a journey out of one’s home or town in order to partake in ritual or witness an event.

The self is constituted by others; everybody is somebody’s Jew. Look to the Muslims murdered en masse in the Middle East, harassed and killed in the United States; the war against black lives carried out by cops and klans and right-wing terrorists; the classist eugenics performed on the poor by the extractive networks of capitalism; the Native victims of cultural and natural destruction via unregulated development of indigenous lands; the many displaced by the gentrification of urban space. And no matter who you are, at one point or another in your life, you are your own Jew.

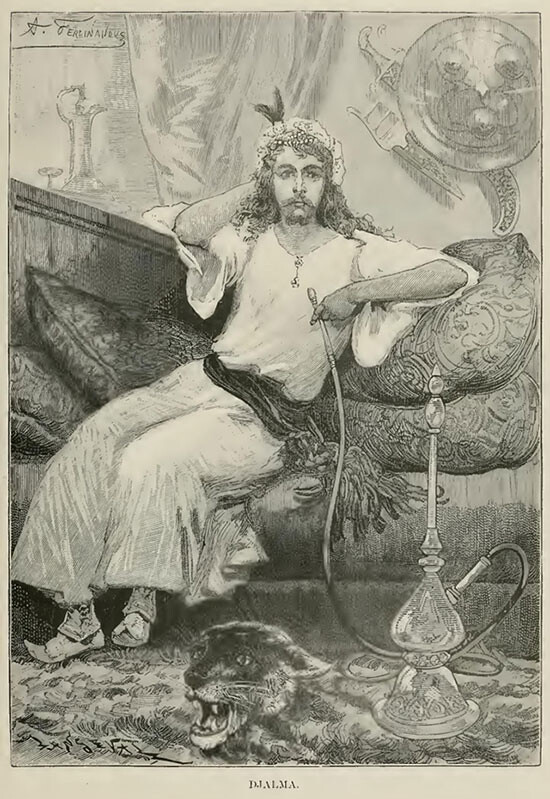

An illustration by A. Ferdinandus in Eugène Sue’s 1844 book The Wandering Jew.

7.

Though I’ve known depression and anxiety my entire life, I didn’t start having full-blown panic attacks until after Trump’s inauguration. For the uninitiated, panic attacks are defined by reverberating, surging loops of dread that consume you. The heart beats uncontrollably; the mind races faster and faster and repeatedly concludes that you simply must be dying. The first full-blown panic attack I had, in early 2017, involved allergy medication. I take two meds, Montelukast in the evening and Fexofenadine in the morning. One day, I ran out of the Fexofenadine and double-dosed on the Montelukast. After taking the pill, I made the critical error of smoking weed. The fear and psychosis quickly started to build within me; the newfound architecture of political anxiety had opened a local chapter. It felt like I was dying, and I became convinced that I was going into shock from the second allergy pill. My body trembled, I couldn’t catch my breath. It took me calling Poison Control and being told that I couldn’t die from two Montelukasts in order for me to eventually calm down. No one is perfectly heretical, and there are some things about my Abrahamic makeup that I just can’t profane.

Allergies, like paranoia, are assigned as a stereotypical quality of Jewishness.

Ashkenazi Jews are in fact more prone to disease because of their pure-bred genetic makeup. After a little research though, it seemed my Jewishness was probably not the reason for my severely runny nose and congestion—this is just a stereotype. Allergies, it’s been found, have been rising in general over the past couple years due to global climate change: warming climates from the industrial pumping of carbon dioxide into the air—the wholesale gassing of the planet—mean longer pollen seasons and more mold.6 This, of course, is one of our lesser worries in the Anthropocene, but it hints at a deeper set of questions. How will the sediments of knowledge continue to shift our paranoias? Will they stoke or dampen the flames of delusion? How does anxiety, one of the most common mental-health issues in the world, relate to our emerging political subjectivity? And, if the pessimist in me is right, and we’re actually living in early capitalism, what will this mean for the global future?

Generalized Anxiety Disorder is what my therapist told me, and I didn’t need any convincing.

WEB.jpg,1600)

WEB.jpg,1200)

Flowers bloom in Washington Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY.

8.

A couple months ago it was reported that dozens of headstones were knocked down in Washington Cemetery, a Jewish graveyard in Brooklyn. The same thing happened at the Chesed Shel Emeth cemetery in St. Louis, where one hundred headstones were toppled, and many broken, in February. That act of vandalism in St. Louis was during a wave of over one hundred bomb threats made to Jewish community centers across the US, which caused evacuations and intensified fears about a new tide of anti-Semitism in the United States following the inauguration. It turned out that an eighteen-year-old Jewish teenager in Israel—who has a brain tumor that affects his behavior, according to his lawyer—was the primary (but not sole) source of these bomb threats.

In Washington Cemetery, I look around and see some tombstones that are sort of slouching, a couple that are fully knocked over. The NYPD had recently finished their investigation and ruled that it was not the work of vandals, and was rather the result of neglect and soil erosion instead, though the cemetery disputes this. I wonder if this was anti-Semitic vandalism, or just the result of environmental slippage and a ploy by the cemetery. The landscaping of the graveyard is unmanicured, allowed to run wild with tall grasses and dandelions. I sit with the dead; they’re a calming force sometimes.

9.

In April 2017, Gean Moreno gave a lecture called “A Fascinating Prospect,” on the work of imagining human extinction, which “reminds us that we are the outcome of processes that were set in motion long before we were around and that will continue long after we are gone, processes that will fold us back into their unbroken line of incessant mutation, swallowing any trace we leave behind.”

Moreno acknowledges the dazzling phenomenon of our evolved processes, things like metabolism and other little labors that sustain life, only to remind us that we’re “a swarm of chemical and informational transactions.” In our current global project of imagining human extinction (not totally new, but it has come with something especially obsessive and rational about it as of late), the possibilities are not remote: they are literally written in the earth’s geology, communicated in the eyes and stories of the anguished.

After the talk was over, I went to the bar to grab another Chardonnay, and saw the printed text of the lecture in the trash. I retrieved it and walked outside. I glanced at a line: “an incapacity to affect our immediate and material conditions and political landscapes, of a swelling sense of impotence before incessant crisis and social disintegration.” Downstairs, I gazed up to see the sign that hung next to the entrance. It read “Ritualarium,” with Hebrew letters beneath it. This, I found, is the last Mikveh in the Lower East Side, the ritual bath used by Orthodox Jews where individuals are immersed for purification. This was the meeting place for the Federation of Jewish Organizations of New York State, who protested the Russian pogroms happening at the turn of the twentieth century, and the stricter immigration laws that were being put in place by the United States.7

As the night drew on, I wondered stupidly if the total extinction of humanity is our only chance at true peace. It isn’t, of course, though it certainly seems like the most visible strategy at the moment. Beyond a transaction with this bleak horizon, and the task of giving recognition to suffering in all its forms—the labors of empathy, memory, reparation, and defense—there’s another labor that must be integrated: the work of forgetting.

The last time I saw my Uncle Morty, he asked me if I had a girlfriend, and told me that it was important to have a body that could keep you warm at night. This is something I like to forget; it was creepy and made me uncomfortable, despite its kernel of truth. Forgetting, you see, is different from amnesia; it has a political function. Born in the Ukraine in 1772, Rebbe Nachman was the founder of Breslov, a Hasidic group that encouraged joy and dancing as a means of getting closer to God. He wrote, “Most people think of forgetfulness as a defect. I consider it a great benefit. Being able to forget frees you from the burdens of the past.” Remembrance and the archive are integral, but the mind and culture cannot always be crowded with the objects of our opposition, the source of our demise. What we strive for must exist—for now—within, underneath, and through the structures of extinction.

10.

Inmate Bedrich Fritta, who was imprisoned at the Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia, placed numbered suitcases and bundles of belongings near a fence and some dead trees in order to signify that the owners had been exterminated. This was a form of art, created within the camps as a disavowal of power, disobedience in the face of dehumanization. It was instrumental and communicative.

Three years ago I encountered a contrary image: a favela sat in the bright Basel sun. It was just outside the Messeplatz, the two massive convention halls made of basket-weaved brushed aluminum, which are conjoined at the center by an enormous oculus—a silver wormhole to the sky. Architects Herzog & de Meuron designed it with the weaving pattern in order to reduce the sense of scale, but still, it remains huge and imposing. Favela Café was an art installation on the occasion of Art Basel 2013, a mini-shantytown of stained wood pallets and corrugated metal roofs. The structures, meant to invoke Brazilian slums, were clean and simply constructed, not very slum-like. They served as concession stands for coffees and Aperol Spritzes and various pastries. A few days into the fair, I heard the booms of teargas guns being fired by Swiss police. They were breaking up a group of about one hundred artist-activists who partied, vainly, in protest. After the demonstrators were maced, arrested, and driven out, everything got cleaned up, and the point-of-sale art installation continued providing lattes and dappled shade.

11.

Just down the street from the Miami Beach Convention Center where Art Basel is held, the Holocaust Memorial’s outstretched arm explodes out of the earth, bodies flailing on its forearm, all in a bronze-green patina. The marketplace for memorializing is a tiny blip in the larger nexus of the speculative fine-art market. As Claire Fontaine remarked on a not-too-distant past, “The market was only one background noise among many, and not yet the endless, deafening throbbing we have now grown accustomed to.”8 What is the function of art and the memorial in the age of contemporary fascism?

There’s a reason we find hope in the black-clad antifa punching a white nationalist, and the memes set to a thousand songs. There’s a reason we’re pulling down those statues of white men.

12.

In his review of the Jewish Museum’s “Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery/Recent Art” (2002), Peter Schjeldahl wrote, “We were afraid that Adolf Hitler would keep making us feel bad forever, but you know what? He’s dead, and we’re not.”9

This quote from Schjeldahl is meant to provide some dark comic relief and, within that, some modicum of hope. Still, the mind remains a concentration camp for thought, a site of both desire and repulsion, hopelessly attracted to history’s mass extinctions and the political vocabularies that animate them. History is like food for the mind, and we feast on the dead. Sontag: “The appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.”10 I return to this subject of genocide repeatedly—sick of it the way Celan was sick of his much-anthologized poem “Death Fugue.” It feels played-out, and yet, the desire and necessity for it gets periodically inflamed. Yes, Hitler might be dead, what about all the others? Is there no way out?

Recently, in Lithuania, a hundred-foot tunnel was discovered at Ponar, the site of multiple mass graves where Nazis buried murdered Jews during the Holocaust. The tunnel was dug with spoons.11

13.

My family’s deaths in the Holocaust have haunted me ever since I was a child. This was despite the void of information, the lack of specific horror stories. The haunting was given shape by the traumas that affected me directly, the various dismemberings: some universal, others singular. So the Holocaust took on greater meaning, perhaps, as a way of coping with my everyday struggles, the traumas of family, the polluted self.

When I reached out to one of Uncle Morty’s daughters about what happened to the family during the Holocaust, after her grandfather returned to Poland from the Siberian labor camp, she corrected me and said that she heard that he had fought in World War I. She said that Uncle Morty told many lies. I was unprepared. My sense of identity flashed before my eyes. Okay, but did any family die in the camps? “I think some of the family that did not leave died in the camps,” she said. At the moment, the question remains unanswered, a knot only made tighter by inquiry, a lacuna that has left me wondering, wandering.

In college I took a class called “Comparative Genocide,” and Dr. Olson, the professor, gave us a sheet containing his twin-spiral model of the progression of genocide. It had two neat spirals next to each other. They illustrated the social processes of othering and dehumanization that lead to the systematic murder of a targeted group of people, and one day, after watching a portion of the documentary Shoah, I walked in the heat of Miami to my car. “The Fair,” the county fair on the grounds close to the university, was alive and rowdy with the yells of roller-coaster riders. It was fall, but it felt like the dead of summer. As I stood there, perspiring and listening to those yelling in absolute ecstasy, my eyes welled up, the tears mixed with my sweat. The screams of joy were transmogrified, forever engraved in my mind.

This is the labor of memory. As we walk through history, the lushest of forests, we find the engravings and trash of those who have come before. Obsessed with finding our way out, or with securing our patch of ground, we do the work that’s bestowed upon us, the work we take on, deal with (and dole out) trauma, reckon with ourselves and with others, confuse stimuli and signals and try to interpret them as best we can. This labor includes far too many moments of flesh-crawling horror. What if my family wasn’t a part of the Holocaust? Does that invalidate my work? Does it negate all the times I was a victim of anti-Semitism in all its forms, pernicious and casual? Am I still in intimate relation with one of the darkest moments in human history? Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. The labor of memory is traumatic, but what makes trauma trauma is how easily we find ourselves returning to it again and again, like a beautiful poem. Lucky are those who travel through the cycles of shame and doubt and trembling, for theirs is a familiar—and familial—world. As Celan wrote:

Iris, swimmer, dreamless and dreary:

the sky, heart-grey, must be near.12

Like all of us, I am still seeking answers and some sort of relief, learning to remember, remembering to forget.

Jacques Derrida, “Paul Celan and Language,” in Paul Celan: Selections, ed. and trans. Pierre Joris (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 204.

Sigmund Freud, “The ‘Uncanny,’” 1919 →.

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 166.

Isaac Deutscher, “Message of the Non-Jewish Jew” →.

Ilan Pappé, “Ship of State,” Bookforum, October–November 2005 →.

Umair Irfan, “Climate Change Expands Allergy Risk,” Scientific American, April 30, 2012 →.

See Kate Newman, “To Find the Lower East Side’s Last Mikvah, Look For the Sign That Says ‘Ritualarium,’” Bedford + Bowery, December 30, 2013 →.

Claire Fontaine, “Our Common Critical Condition,” e-flux journal 73 (May 2016) →.

Peter Schjeldahl, “The Hitler Show,” New Yorker, April 1, 2002 →.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2004), 33.

Nicholas St. Fleur, “Escape Tunnel, Dug by Hand, Is Found at Holocaust Massacre Site,” New York Times, June 29, 2016 →.

Paul Celan, “Language Mesh” (1959), in Poems of Paul Celan, trans. Michael Hamburger (London: Anvil Press Poetry, 1995).