for KW

Is it really our duty to add fresh ruins to fields of ruins?

—Bruno Latour

Have you heard that reality has collapsed? Post-truth politics, the death of facts, fake news, deep-state conspiracies, paranoia on the rise. Such pronouncements are often feverish objections to a nightmarish condition. Yet inside the echo chamber of twenty-first-century communication, their anxiety-ridden recirculation can exacerbate the very conditions they attempt to describe and decry. In asserting the indiscernibility of fact and fiction, the panicked statement that reality has collapsed at times accomplishes little but furthering the collapse of reality. Proclaiming the unreality of the present lifts the heavy burdens of gravity, belief, and action, effecting a great leveling whereby all statements float by, cloaked in doubt.

Against this rhetoric, a different proclamation: I want to live in the reality-based community. It is an imagined community founded in a practice of care for this most fragile of concepts. My desire, to some, is pitifully outmoded. Already in 2004, a presidential aide—widely speculated to be Karl Rove, deputy chief of staff to George W. Bush—told New York Times journalist Ron Suskind that any attachment to the considered observation and analysis of reality placed one hopelessly behind the times:

The aide said that guys like me were “in what we call the reality-based community,” which he defined as people who “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.” I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism. He cut me off. “That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.”1

Faced with such imperial fabrication, the likes of which have only intensified in the years since Rove’s statement, the “judicious study of discernible reality” becomes a task of the greatest urgency—not despite but because so many claim it is not the way the world really works anymore. I, too, attended all those graduate school seminars in which we learned to deconstruct Enlightenment principles and mistrust empiricism, but given the state of things, it’s starting to look like they might need salvaging.

*

Imagined communities are called into being through media, and the reality-based community is no different. Documentary cinema is its privileged means of imagination. Why? With a frequency not found in other forms of nonfiction image-making, documentary reflects on its relationship to truth. And unlike the written word, it partakes of an indexical bond to the real, offering a mediated encounter with physical reality in which a heightened attunement to the actuality of our shared world becomes possible. But precisely for these same reasons, documentary is simultaneously a battleground, a terrain upon which commitments to reality are challenged and interrogated. To examine the vanguard of documentary theory and practice over the last thirty years, for instance, is to encounter a deep and pervasive suspicion of its relationship to the real and, more particularly, a robust rejection of its observational mode, a strain that minimizes the intervention of the filmmaker, eschews commentary, and accords primacy to lens-based capture.2 In the glare of the present, these arguments must be revisited and their contemporary efficacy interrogated.

In the 1990s, the advent of digitization sparked new fears that photographs could no longer be trusted. The spectre of easy manipulation hovered over the digital image, threatening its evidentiary value. Reality was seen to be an effect of images rather than their cause; photographic truth was debunked as a discursive construction, the power of the indexical guarantee deflated.3 Postmodernism heralded a realignment of epistemological foundations, with notions like historicity, truth, and objectivity coming under interrogation. Textualism reigned. If all images are the product of convention, of the play of codes, then what is the difference between fiction and nonfiction? As the argument went, reality, fiction, it makes no difference, everything is a construction, we live in a forest of signs. Jean Baudrillard infamously posited that we were experiencing a fading of the real, a pervasive derealization he saw as intimately linked to technology and in particular to technologies of image reproduction like cinema and television, which offer powerful-yet-bogus impressions of reality in the absence of reality itself. In a chapter called “The Murder of the Real,” Baudrillard offered his diagnosis in a typically totalizing manner: “In our virtual world, the question of the Real, of the referent, of the subject and its object, can no longer even be posed.”4

These conditions understandably provoked a crisis for documentary. As Brian Winston put it in 1995, “Postmodernist concern transforms ‘actuality,’ that which ties documentary to science, from a legitimation into an ideological burden.”5 The assault on documentary came from both sides: its authority was eroded by simulationism’s liquidation of referentiality, but occurred equally in the name of a progressive politics, as part of a critical project that sought to dismantle false, ideological notions like objectivity, authenticity, and neutrality—spurious concepts that had long denied their constructedness, masquerading instead as essences that concealed complicity with a will to power.

This crisis was, like so many are, a catalyst of rejuvenation. An efflorescence of “new documentary,” as Linda Williams called it in a landmark 1993 text, responded to technological change and epistemological uncertainty by turning to reflexivity, artifice, and performativity.6 These films took seriously postmodern critiques, but rather than succumb to cynicism, they foregrounded the construction of contingent truths. They took up strategies of reenactment, essayism, heightened subjectivism, and docufiction, delighting in precisely those forms of contamination once deemed anathema, and were accompanied by an efflorescence of critical writing that sought to take stock of these developments. The “blurring of boundaries” was held to be an inviolably noble goal. As the new millennium began, critics would repeatedly point to precisely these characteristics as typical of contemporary art’s “documentary turn.” For some, these strategies were evidence of a sophisticated approach to questions of truth that favorably differentiated them from that poor straw man, “traditional documentary.”7

Eric Baudelaire, Also Known as Jihadi, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Paul Arthur has noted that each period of documentary is engaged in a polemical contestation of the one before it,8 and the 1990s are no exception. Through all of these calls for impurity, through all of this lobbying for the salience of precisely those techniques once outlawed by documentary orthodoxy, a bad object emerged: the observational mode, indicted for an apparently positivist belief in the real and a disavowal of mediation. The problem with this form of “traditional documentary” was that it was understood as asserting, rather than questioning, its relationship to reality. It lacked the requisite reflexivity. Or so the argument went—in propping up observational documentary as a bad object, its aims and strategies were at times prey to oversimplification. Whether implicitly or explicitly, critics, artists, and filmmakers positioned at the intersection of documentary and art decried the naturalistic capture of phenomenal reality as a stupid fetish: stupid, because it relied on the machinic dumbness of copying appearances rather than the creative transformations associated with artfulness; a fetish, since its impression of immediacy was a mystification in desperate need of unveiling by the non-duped who know better and acknowledge the constructedness of all representation. The notion that cinema suffers when it simply duplicates appearances goes back to Grierson’s renowned dictum that documentary is the “creative treatment of actuality,” and even farther, to 1920s film theory, where it is deeply tied to claims for film as art.9 It is unsurprising, then, that when documentary entered contemporary art, a similar phobia of the facticity of recording accompanied it, amplified by a theoretical climate still indebted to postmodernism and poststructuralism. Of course, lens-based capture persisted as a means of making images, but its unadorned primacy, the idea that it offers privileged access to unstaged reality, was the sacrificial lamb at a postmodern slaughter. The very title of Williams’s essay, “Mirrors Without Memories,” underlines the historical unavailability of the observational mode at her time of writing: she proposes that the photographic image is not, as Oliver Wendell Holmes suggested in 1859, a mirror with a memory but rather “a hall of mirrors.”10 Winston went even farther, wagering that documentary’s very survival depended on “removing its claim to the real”; it was best to “roll with the epistemological blow, abandoning the claim to evidence.”11

More than twenty years later, nothing and everything is different. The toxic erosion of historical consciousness continues unabated. The constructivist pressure on truth and objectivity feels stronger than ever—indeed, such notions lie in ruins—but the emancipatory potential that initially accompanied the articulation of this critique has dissipated. We live in an age of “alternative facts,” in which the intermingling of reality and fiction, so prized in a certain kind of documentary practice since the 1990s, appears odiously all around us. Questioning documentary’s access to the real was once oppositional: it broke away from a pseudoscientific conception of documentary that saw truth as guaranteed by direct inscription. When Trinh Minh-ha wrote in 1990 that “there is no such thing as documentary,” she wrote against this ingrained tradition.12 But many of the things for which Trinh advocated are now commonplace. Experimental documentary did largely follow Winston’s call to abandon its claim to evidence, foregoing fact for “ecstatic truth,” Werner Herzog’s term for a truth “deeper” than that offered by the observation of reality, accessible only through “fabrication and imagination.”13 There is a lurking Platonism here: appearances are understood as deceptive seductions incapable of leading to knowledge. Meanwhile, essay films—with their meditative, questioning voice-overs—are everywhere, a veritable genre. The notion that we best access reality through artifice is the new orthodoxy.

Eric Baudelaire, Also Known as Jihadi, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

No one assumes any longer, if they ever did, that there is a mirrored isomorphism between reality and representation or that the act of filming can be wholly noninterventionist. To assert such things is to tell us what we already know. And so why does it happen so often, whether explicitly or implicitly, in documentary theory and practice? What does it accomplish? Perhaps it is just inertia, a repetition of received ideas that stem from a paradigm by now firmly established. Perhaps. Yet it also reconfirms a smug and safe position for maker and viewer alike, guarding both against being caught out as that most sorry of characters: the naive credulist. We all know better than to believe. This might be called media literacy, but it also contains a whiff of the cynicism Williams hoped the “new documentary” would ward off. We breathe the stale, recirculated air of doubt.

Already in 1988, Donna Haraway recognized that though the critique of objectivity had been necessary, there were dangers in proceeding too far down the path of social constructivism.14 She warned that to do so is to relinquish a needed claim on real, shared existence. Our planet is heating up. In the realm of documentary, too, there is a visible world “out there,” the traces of which persist in and through the codes of representation. It is a world that demands our attention in all its complexity and frailty. A pressing question emerges: Is putting documentary’s claim to actuality under erasure through reflexive devices in all cases still the front-line gesture it once was, or have such strategies ossified into clichés that fail to offer the best response to the present emergency? In light of current conditions, do we need to reevaluate the denigration of fact inherent in the championing of “ecstatic truth”? This is not to diminish the tremendous historical importance of such strategies, which can remain viable, nor to malign all films that engage them. At best—and there are countless examples of this—departures from objective reality are enacted in order to lead back to truth, not to eradicate its possibility. At worst, the insistence that documentary is forever invaded by fictionalization leads to a dangerous relativism that annuls a distinction between truth and falsity that we might rather want to fight for. And across this spectrum, we find an underlying assumption that today requires interrogation: namely, that the task of vanguard documentary is to problematize, rather than claim, access to phenomenal reality.

Instead of taking for granted that there is something inherently desirable about blurring the boundary between reality and fiction and something inherently undesirable about minimizing an attention to processes of mediation in the production of visible evidence, we must ask: Do we need to be told by a film—sometimes relentlessly—that the image is constructed lest we fall into the mystified abyss of mistaking a representation for reality? Or can we be trusted to make these judgments for ourselves? If, recalling Arthur’s formulation, every age of documentary rejects and responds to the last, perhaps now is the time for a polemical contestation of the denigration of observation. To echo Latour, the critique of documentary constructedness has run out of steam.15

*

The interest of documentary lies in its ability to challenge dominant formations, not to conform to or mimic them, and yet uncertainty and doubt remain its contemporary watchwords, especially as it is articulated within the art context. What would it be to instead affirm the facticity of reality with care, and thereby temper the epistemological anxieties of today in lieu of reproducing them? How might a film take up a reparative relation to an embattled real?16 It might involve assembling rather than dismantling, fortifying belief rather than debunking false consciousness, love rather than skepticism.

As a rule of thumb, bad objects do not stay bad objects forever; they make unsurprising returns to favor when the time is right. In the work of a number of important artists and filmmakers, a commitment to a reconceived observational mode is visible. These works leave behind a pedagogy of suspicion and instead assert the importance of the nonhuman automatism of the camera as a means for encountering the world. Departing from the now dominant paradigms of ecstatic truth and the essay film, they look to the facticity of phenomenal reality and demand belief in it. I can hear the objections: this is a return to positivism, a guileless trust in the transparency of representation, a forgetting of all of the lessons we have learned. In fact, no. This is no simple throwback to the positions of direct cinema, which have, in any case, been unfairly characterized. Abstaining from techniques that pry open the interval between reality and representation, including voice-over commentary, these films revive key elements of the observational mode while challenging the epistemological claims that historically accompanied it through strategies of partiality, blockage, and opacity. They seek not to master the world but to remain faithful to it,17 creating for the viewer a time and space of attunement in which a durational encounter with alterity and contingency can occur, with no secure meaning assured.

Film still from Libbie D. Cohn and J.P. Sniadecki’s documentary People’s Park (2012).

The films made by individuals affiliated with Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab manifest diverse concerns and take up divergent formal strategies. Nonetheless, across works such as Leviathan (2012, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel), People’s Park (2012, Libbie D. Cohn and J.P. Sniadecki), Manakamana (2013, Stephanie Spray and Pacho Velez), and The Iron Ministry (2014, J. P. Sniadecki), one encounters a shared reassertion of the possibilities of observation. These practices pursue ethnography through cinema rather than through the written discourse privileged by disciplinary anthropology, and thus it is fitting that the conception of the moving image one finds within them seizes on the non-coded powers of lens-based capture rather than the reductive linguistic paradigm of codedness proper to theorizations of film inspired by Saussurean semiotics. These films retreat from any posture of domination to instead provide thick description of the irreducible complexity of the world, its vital excessiveness and ambiguity. The modalities of vision one finds within them are never that of a dislocated camera-eye that would assert possession of the profilmic through the agency of the gaze. They are, rather, eminently situated and specifically cinematic. In Leviathan, GoPro cameras are strapped to laboring bodies and thrown into the ocean. In People’s Park, a seventy-eight-minute long take is filmed from a wheelchair that winds its way through a park in Chengdu, grounding the unfolding images within a spatiotemporal continuity and asserting the primacy of the filmed object over and above the subjective interventions of the filmmakers. In Manakmana and The Iron Ministry, the cable car and the train carriage, respectively, form enclosures that assure the mutual implication of filmmaker and subject. And in all four films, an unobtrusive acknowledgement of mediation is discernible in strong yet varied assertions of structure that intensify, rather than erode, their claims on actuality.

To say that observation is today experiencing a rehabilitation is not to suggest that commitments to it have been wholly absent in recent decades. Harun Farocki is often closely associated with the tradition of the essay film, but maintained for over thirty years a consistent practice of observational documentary, often, as Volker Pantenburg has noted, filming situations “marked by a sense of repetition and rehearsal” so as to install a degree of reflexivity at the level of the filmed scene.18 Even though many of these works were television commissions, this investment by no means waned following Farocki’s entry into the art context. He deemed Serious Games (2009–10) a “Direct Cinema film,”19 and in many ways it is: Farocki carefully details the use of video game simulations for solider training and post-combat rehabilitation without intervening and refrains from offering any commentary until the limited intertitles of the fourth and final segment, “A Sun With No Shadow.” In an interview with Hito Steyerl, he rather unfashionably proclaimed himself a “devotee of cinéma vérité,” just as he was beginning the observational project Labour in a Single Shot (2011–14), a collaboration with Antje Ehmann.20 The pair conducted filmmaking workshops in fifteen cities around the world in which people made single-shot films, one to two minutes in length. Aside from taking labor in a broad sense as their subject, these films were governed by only one rule: as the title of the project suggests, there could be no cuts, a parameter that forges an association with the preclassical actualité and preserves the continuity of time. Despite this policy of montage interdit, there is no presumption of total capture: the films’ short lengths bespeak a rejection of totality. They are but fragments of larger processes that remain largely out of frame.

Eric Baudelaire, Also Known as Jihadi, 2017. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view at Contour Bienniale 2017.

When shown at the eighth edition of the Contour Biennale in Mechelen, Belgium, Eric Baudelaire’s Also Known as Jihadi (2017) was presented in the sixteenth-century Court of Savoy, once the seat of the Great Council and now the home of the lower civil and criminal courts—a setting that underlined the film’s engagement with the production of truth. In one regard, the film is a remake of Masao Adachi’s 1969 masterpiece A.K.A. Serial Killer, in which the director tests his notion of fûkeiron—landscape theory—which posits that social forces become visible through observation of the built environment. Following Adachi, Baudelaire’s film is composed of a series of long shots of locations once traversed by a pathologized protagonist, in this case, Abdel Aziz Mekki, accused of travelling from France to Syria to participate in jihad. But Baudelaire departs significantly from the Japanese filmmaker by adding a second component to his filmic vocabulary: legal documents from the investigation into Mekki’s activities, introduced between the landscape shots. The film thus engages in a comparative staging of two apparatuses tasked with the production of truth—observational documentary and the legal system—both of which are grounded in an evidential recording of reality that Baudelaire shows to exist at a remove from any guarantee of understanding. We are presented with evidence, yet Mekki’s motivations remain elusive. Also Known as Jihadi poses the epistemological potential of fûkeiron as a question rather than taking it as a given, but the film’s very existence demonstrates Baudelaire’s conviction that this is a question worth asking. There is no overt manipulation of the image, no voice-over to direct the viewer through a poetic meditation on the impossibility of truth, no reenactment. Also Known as Jihadi is an open inquiry into how the media of law and documentary might—the conditional tense is fundamental—produce knowledge and how they might fail. The film’s empty landscapes and reams of documents lead not to the arrogance of singular truth but to a suspended interval in which a humble reckoning with the limits of comprehension and the inevitability of unknowing occurs.

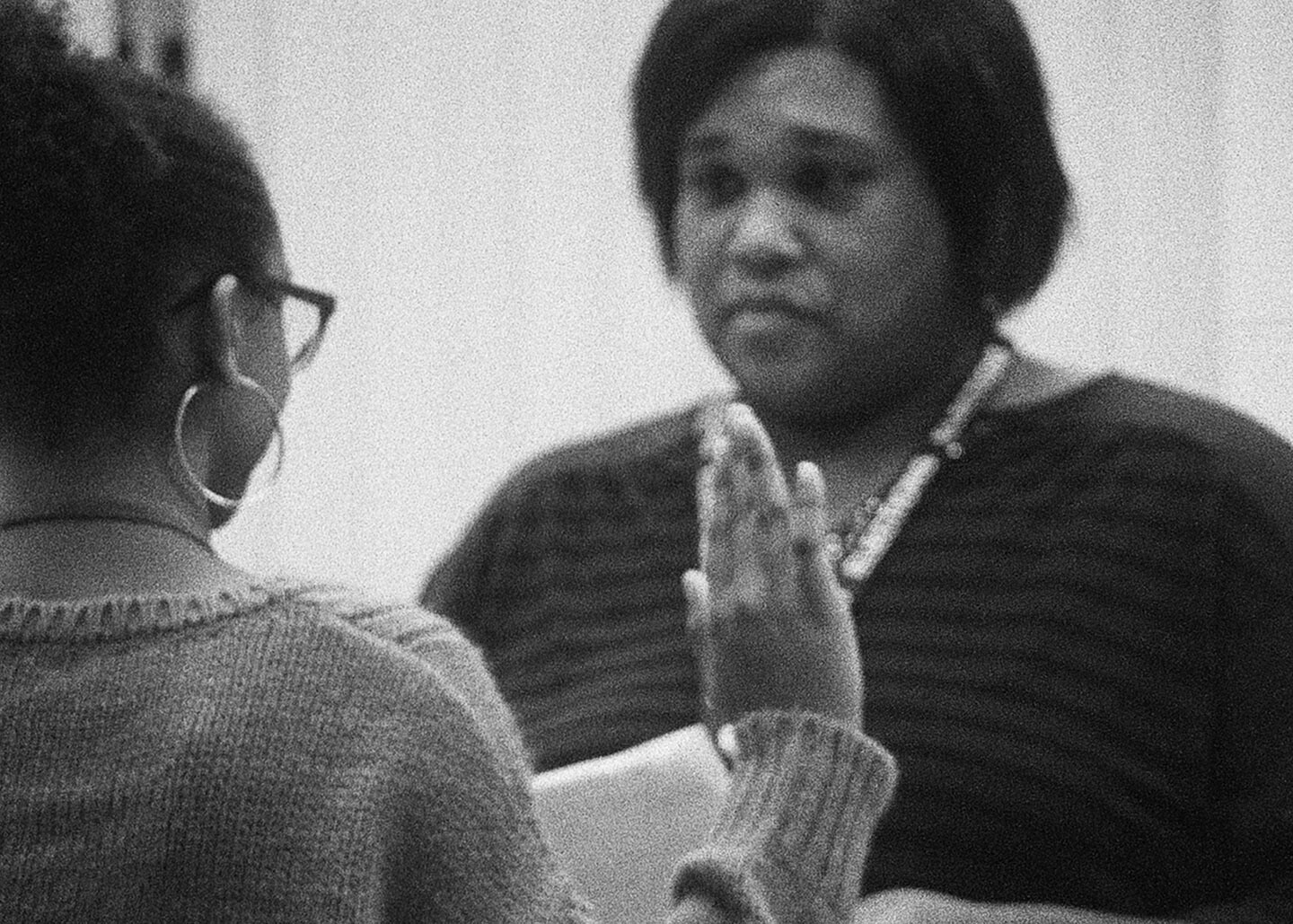

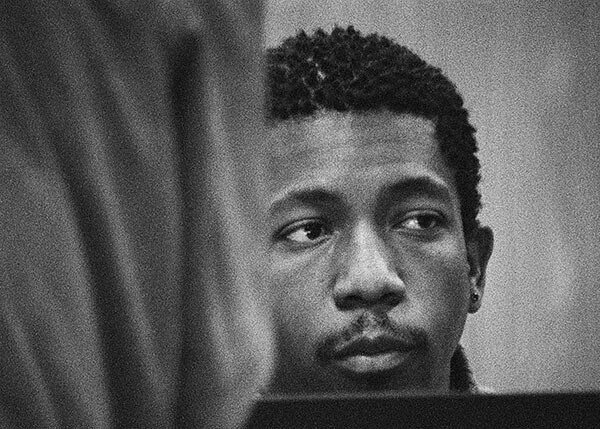

If there is one film that most powerfully underlines the stakes of rehabilitating observation, it is Tonsler Park (2017), Kevin Jerome Everson’s eighty-minute portrait of workers at a polling station in the titular area of Charlottesville, Virginia, on November 8, 2016—the day the current president of the United States was elected. Using black-and-white 16mm film, Tonsler Park consists of a series of long takes of the mostly African-American women who facilitate the voting process for members of the local community. For privacy reasons, Everson did not record synchronized sound; instead, images shot with a telephoto lens are accompanied by wild sound captured in the same place and on the same day, though not at precisely the same moment as the image. This slight cleavage of image and sound ruptures any possible impression of total capture, ushering the film away from discredited notions of immediacy. This refusal of mastery is buttressed by the position of Everson’s camera, which is out of the way, at some distance from the poll workers who form the ostensible focus of the scene. People pass frequently in front of the lens, close enough that only their torsos are visible. They intermittently fill the frame with vast fields of grey and black, creating what Everson has called, with reference to that most reflexive of avant-garde film genres, a “human flicker.” The fullness of this reality does not yield to the camera. It is grainy, monochrome, obstructed. Vision is blocked, yet the film demands that we look nonetheless, that we look closely at an event at once quotidian and historic, at people and activities that might otherwise never be held up to view.

Foucault was right when he deemed visibility a trap. Exposure is violent; it makes the surveilled subject vulnerable to capture by apparatuses of power. Moreover, to see something clearly, fully, can easily slide into the mistaken assumption that it is known, comprehended in its totality—which is itself a form of violence, as Glissant has shown. But before romanticizing the escape of invisibility, we must remember that to be invisible is also to be cast out of the body politic, into the precariousness of ungrievable life. Visibility is, then, deeply ambivalent, particularly for populations more subject than others to police harassment and violence and more excluded than others from myriad forms of representation, as African-Americans are. Tonsler Park’s dialectics of revelation and concealment gets to the heart of this ambivalence and does so, no less, by capturing a day that would inaugurate a regime that would only exacerbate this double violence.

To watch Tonsler Park is to give oneself over to a phenomenology of gesture, comportment, and detail achieved through the presentation of images shorn of any great eventfulness. Through this heightened attunement, the film opens a protracted duration in which the concrete specificity of the represented event shares mental space with farther-reaching thoughts to which it gives rise: the first presidential election after Barack Obama’s two terms, of which we know the disastrous results but the onscreen figures do not; the racialized and gendered dimensions of work; widespread voter suppression through the implementation of registration laws that disproportionately affect African-Americans; the permanent disenfranchisement of convicted felons in many states, once again disproportionately affecting African-Americans; the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its place within the Civil Rights Movement, many demands of which we must continue to levy. None of these threads enter Tonsler Park as information supplied directly by Everson or his subjects. Rather, through its clearing of time and presentation of a world to be witnessed—an encounter markedly different from the experience one might have if present at the filmed event—the film activates a labor of associative thought on the part of the spectator. Here, observational cinema facilitates a form of thinking with appearances that depends simultaneously on the image’s ties to phenomenal reality and the image’s differences from it.

Film still from Kevin Jerome Everson’s Tonsler Park (2017). 80”, 16mm, b&w, sound. Copyright: Kevin Jerome Everson; Trilobite-Arts DAC; Picture Palace Pictures.

*

The documentary claim on the capture of life has historically been tied to domination, and in many cases still is, but this is not its only possibility. Following the devastation of World War II, critics such as Siegfried Kracauer and André Bazin found in the registration of reality possibilities of reparation and redemption; in our moment of ecological, humanitarian, and political crisis, the nurturing of this capacity possesses a comparable urgency. That documentary practices take up this task with vigor is all the more crucial given that the importance of profilmic reality is swiftly diminishing in much popular cinema. Even far beyond the genres of science fiction and fantasy, in apparently “realistic” films, computer-generated images fill screens with dreams of a world wholly administered, controllable down to the last pixel, drained of contingency. As the anthropocentric perfection of the CGI simulacrum is increasingly dominant, and as the rhetoric of a collapse of reality serves only those who seek to further it and benefit from it, there must be a thorough rehabilitation of the viability of observation in vanguard documentary. To be sure, there is ample evidence that this is already well underway in practice, in the films mentioned here and in recent works by Maeve Brennan, Chen Zhou, Ben Russell, Wang Bing, and many others. This is by no means to call for an invalidation of those strategies associated with the “new documentary”; let one hundred flowers bloom, so long as they avoid the pestilence of postmodern relativism. Rather, it is simply to insist that the aspersions cast for so long on the facticity of recording must cease. Creativity and sophistication are not found only in fictionalization, intervention, and proclamations of subjectivity. The appearances of the world need our care more than our suspicion. Giving primacy to the registration of physical reality can do something that “ecstatic truth” cannot: reawaken our attention to the textures of a world that really does exist and which we inhabit together.

There is nothing naive about the relationship to reality found in the examples mentioned here; in fact, they place an immense trust in their viewers. Truth is not out there waiting to be captured—but reality is. In the encounter with facticity made possible by these films, it becomes clear that to believe in reality is to affirm that we live in a shared world that is at once chaotic and unmasterable. The formal vocabulary of these films differs greatly from that most associated with direct cinema: they do not spontaneously track reality through a roaming camera, as if it could be fully encompassed by the representational act, but engage in strong, deliberate assertions of structure that assert a bond to reality while also marking limits that are at once visual and epistemological. The significance of what one witnesses may remain uncertain, one’s understanding may remain incomplete, and yet there is no doubt as to the reality of what is presented to view, nor of cinema’s ability to provide valuable access to it. All objectivity is situated; all vision is partial. Simple truths and totalizing meanings are the real fictions. Although this may sound like poststructuralism, here these acknowledgements lead not into any hall of mirrors, not to any infinite regress, but assert rather the power of cinema as window, however dirty and distorting its panes may be.

According to Hannah Arendt, the preparation for totalitarianism

has succeeded when people have lost contact with their fellow men as well as the reality around them; for together with these contacts, men lose the capacity of both experience and thought. The ideal subject for totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.21

Looking closely at images that affirm their status as traces of actuality provides one way that we can begin to reestablish the reality of experience and the standards of thought that Arendt rightly deems so important. Within this durational experience, we find ourselves faced with what James Agee called the “cruel radiance of what is.”22 Let us imagine the reality-based community together.

Ron Suskind, “Faith, Certainty, and the Presidency of George W. Bush,” New York Times Magazine, October 17, 2004 →.

Bill Nichols aligns the observational mode with direct cinema and cinéma vérité, characterizing it as stressing the nonintervention of the filmmaker, relying on an impression of real time, the “exhaustive depiction of the everyday,” lacking retrospective commentary, and providing the “expectation of transparent access.” See Bill Nichols, Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 38–44.

For the paradigmatic critique of photographic truth as socially constructed, see John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

Jean Baudrillard, The Vital Illusion, ed. Julia Witwer (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 62.

Brian Winston, Claiming the Real: The Griersonian Documentary and its Legitmations (London: British Film Institute, 1995), 243.

Linda Williams, “Mirrors Without Memories: Truth, History, and the New Documentary,” Film Quarterly 46, no. 3 (Spring 1993): 9–21.

See, for instance, Linda Nochlin, “Documented Success,” Artforum, September 2002, 161–3; Hito Steyerl, “Art or Life? Jargons of Documentary Authenticity,” Truth, Dare or Promise: Art and Documentary Revisited, eds. Jill Daniels, Cahal McLaughlin, and Gail Pearce (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), 6–7.

Paul Arthur, “Jargons of Authenticity (Three American Moments),” Theorizing Documentary, ed. Michael Renov (New York: Routledge, 1993), 109.

This attitude is particularly pronounced in the writings of Ricciotto Canudo. For an extended consideration of this question, see Erika Balsom, “One Hundred Years of Low Definition,” Indefinite Visions: Cinema and the Attractions of Uncertainty, eds. Martine Beugnet, Allan Cameron, and Arild Fetveit (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming).

Williams, “Mirrors Without Memories,” 20.

Winston, Claiming the Real, 259; and Brian Winston, “The Documentary Film as Scientific Inscription,” Theorizing Documentary, ed. Michael Renov (New York: Routledge, 1995), 56.

Trinh T. Minh-ha, “Documentary Is/Not a Name,” October 52 (Spring 1990): 76.

In his 1999 “Minnesota Declaration,” Werner Herzog calls the truth of cinéma vérité “a merely superficial truth, the truth of accountants,” and opposes to it the “deeper strata” of “poetic, ecstatic truth” that “can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.” See Werner Herzog, “Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Cinema,” →.

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 575–99.

Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry 30 (Winter 2004): 225–48.

As a practice of love that seeks to repair damage and move beyond negative affects, this attitude shares aspects of Eve Sedgwick’s notion of reparative reading. See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 123–51.

Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 593–94.

Volker Pantenburg, “‘Now that’s Brecht at last!’: Harun Farocki’s Observational Films,” Documentary Across Disciplines, eds. Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg (Berlin/Cambridge: Haus der Kulturen der Welt and MIT Press, 2016), 153.

Harun Farocki, “On the Documentary,” in “Supercommunity,” special issue, e-flux journal 65 (May 2015) →.

Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl, Cahier #2: A Magical Imitation of Reality (Milan: Kaleidoscope Press, 2011), 20.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (Orlando: Harcourt Books, 1979), 474.

James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, (1941) 2001), 9.