A Response to Jean-Luc Nancy’s Question “Who Comes After the Subject?”

Both following Hegel and opposed to him, Heidegger proposes Descartes as the moment when the “sovereignty of the subject” is established (in philosophy), inaugurating the discourse of modernity. This supposes that man, or rather the ego, is determined and conceived of as subject (subjectum).1

Doubtless, from one text to another, and sometimes even within the same “text” (I am primarily referring here to the Nietzsche of 1939–46), Heidegger nuances his formulation. At one moment he positively affirms that in Descartes’s Meditations (which he cites in Latin) the ego as consciousness (which he explicates as cogito me cogitare) is posited, founded as the subjectum (that which in Greek is called the hypokeimenon). This also has the correlative effect of identifying, for all modern philosophy, the hypokeimenon and the foundation of being with the being of the subject of thought, the other of the object. At another moment he is content to point out that this identification is implicit in Descartes, and that we must wait for Leibniz to see it made explicit (“called by its own name”) and reflected as the identity of reality and representation, in its difference with the traditional conception of being.

The Myth of the “Cartesian Subject”

Is this nuance decisive? It would be difficult to find the slightest reference to the “subject” as subjectum in the Meditations, and that in general the thesis that would posit the ego or the “I think/I am” (or the “I am a thinking thing”) as subject, either in the sense of hypokeimenon or in the sense of the future Subjekt (opposed to Gegenstandlichkeit), does not appear anywhere in Descartes. By evoking an implicit definition, one that awaits its formulation, and thus a teleology of the history of philosophy (a lag of consciousness, or rather of language), Heidegger only makes his position more untenable, if only because Descartes’s position is actually incompatible with this concept. This can easily be verified by examining both Descartes’s use of the noun “subject” and the fundamental reasons why he does not name the thinking substance or “thinking thing” “subject.”

The problem of substance, as is well known, appears fairly late in the course of the Meditations. It is posited neither in the presentation of the cogito, nor when Descartes draws its fundamental epistemological consequence (that the soul knows itself “more evidently, distinctly, and clearly” than it knows the body), but rather in the third meditation, when he attempts to establish and to think the causal link between the “thinking thing” that the soul knows itself to be and God, the idea of whom is found immediately in itself as infinite being. But even here it is not a question of the subject. The term will appear only incidentally, in its scholastic meaning, in the “Responses to Objections,” set in the context of a discussion about the real difference between finite and infinite, as well as between thinking and extended substances; a problem for which the Principles will later furnish a properly formulated definition. Along with these discussions, we must consider that which concerns the union between body and soul, the “third substance” constitutive of individuality, the theory that will be elaborated in the “Sixth Meditation” and further developed in the Treatise on the Passions.

Considering these different contexts, it becomes clear that the essential concept for Descartes is that of substance—in the new signification that he gives to it. This signification is not limited to objectifying, each on its own side, the res cogitans and the res extensa: it allows the entire set of causal relations between (infinite) God and (finite) things, between ideas and bodies, between my soul and my (own) body, to be thought. It is thus primarily a relational concept. The essential part of its theoretical function is accomplished by putting distinct “substances” into relation with one another, generally in the form of a unity of opposites. The name of substance (that is its principal, negative characteristic) cannot be attributed in a univocal fashion to both the infinite (God) and the finite (creatures); it thus allows their difference to be thought, and nevertheless permits their dependence to be understood (for only a substance can “cause” another substance: this is its second characteristic). Likewise, thought and extension are really distinct substances, having no attributes whatsoever in common, and nevertheless the very reality of this distinction implies a substantial (non-accidental) union as the basis of our experience of our sensations. All these distinctions and oppositions finally find their coherence—if not the solution of the enigma they hold—in a nexus that is both hierarchical and causal, entirely regulated by the principle of the eminent causality, in God, of the “formal” or “objective” relations between created substances (that is, respectively, those relations that consist of actions and passions, and those that consist of representations). It is only because all (finite) substances are eminently caused by God (have their eminent cause, or rather the eminence of their cause, in God) that they are also in a causal relation among themselves. But, inversely, eminent causality—another name for positive infinity—could not express anything intelligible for us except for the “objective” unity of formally distinct causalities.

Thus, nothing is further from Descartes than a metaphysics of Substance conceived of as a univocal term. Rather, this concept has acquired a new equivocality in his work, without which it could not fill its structural function: to name in turn each of the poles of a topography in which I am situated simultaneously as cause and effect (or rather as a cause that is itself only an effect). It must be understood that the notion of the subjectum/hypokeimenon has an entirely evanescent status here. Descartes mentions it, in response to objections, only in order to make a scholastic defense of his realist thesis (every substance is the real subject of its own accidents). But it does not add any element of knowledge (and in particular not the idea of a “matter” distinct from “form”) to the concept of substance. It is for this reason that substance is practically indiscernible from its principle attribute (comprehensible: extension, thought; or incomprehensible: infinity, omnipotence).

There is no doubt whatsoever that it is essential to characterize in Descartes the “thinking thing” that I am (therefore!) as substance or as substantial, in a nexus of substances that are so many instances of the metaphysical apparatus. But it is not essential to attach this substance to the representation of a subjectum, and it is in any case impossible to apply the name of subjectum to the ego cogito. On the other hand, it is possible and necessary to ask in what sense the human individual, composed of a soul, a body, and their unity, is the “subject” (subjectus) of a divine sovereignty. The representation of sovereignty is in fact implied by the ideal of eminence, and, inversely, the reality of finite things could not be understood outside of a specific dependence “according to which all things are subject to God.”2 That which is valid from an ontological point of view is also valid from an epistemological point of view. From the thesis of the “creation of eternal truths” to the one proper to the Meditations, according to which the intelligibility of the finite is implied by the idea of the infinite, a single conception of the subjection of understanding and of science is affirmed, not of course to an external or revealed dogma, but to an internal center of thought whose structure is that of a sovereign decision, an absent presence, or a source of intelligibility that as such is incomprehensible.

Thus, the idea that causality and sovereignty can be converted into one another is conserved and reinforced in Descartes. It could even be said that this idea is pushed to the limit—which is perhaps, for us in any case, the herald of a coming decomposition of this figure of thought. The obvious fact that an extreme intellectual tension results from it is recognized and constantly reexamined by Descartes himself. How can the absolute freedom of man—or rather of his will, the very essence of judgment—be conceived of as similar to God’s without putting this subjection back into question? How can it be conceived of outside this subjection, for it is the image of another freedom, of another power? Descartes’s thought, as we know, oscillates between two tendencies on this point. The first, mystical, consists in identifying freedom and subjection: to will freely, in the sense of necessary freedom, enlightened by true knowledge, is to coincide with the act by which God conserves me in a relative perfection. The other tendency, pragmatic, consists in displacing the question, playing on the topography of substances, making my subjection to God into the origin of my mastery over and possession of nature, and more precisely of the absolute power that I can exercise over my passions. There are no fewer difficulties in either one of these theses. This is not the place to discuss them, but it is clear that, in either case, freedom can in fact only be thought as the freedom of the subject, of the subjected being, that is, as a contradiction in terms.

Descartes’s “subject” is thus still (more than ever) the subjectus. But what is the subjectus? It is the other name of the subditus, according to an equivalence practiced by all medieval political theology and systematically exploited by the theoreticians of absolute monarchy: the individual submitted to the ditio, to the sovereign authority of a prince, an authority expressed in his orders and itself legitimated by the Word of another Sovereign (the Lord God). “It is God who has established these laws in nature, just as a king establishes laws in his kingdom,” Descartes will write to Mersenne (in a letter from April 15, 1630).3 It is this very dependence that constitutes him. But Descartes’s subject is not the subjectum that is widely supposed—even if, from the point of view of the object, the meaning has to be inverted—to be permanently present from Aristotle’s metaphysics to modern subjectivity.

How is it, then, that they have come to be confused?4 Part of the answer obviously lies in the effect, which continues to this very day, of Kantian philosophy and its specific necessity. Heidegger, both before and after the “turn,” is clearly situated in this dependence. We must return to the very letter of the Critique of Pure Reason if we are to discover the origin of the projection of a transcendental category of the “subject” upon the Cartesian text. This projection and the distortion it brings with it (simultaneously subtracting something from and adding something to the cogito) are in themselves constitutive of the “invention” of the transcendental subject, which is inseparably a movement away from and an interpretation of Cartesianism. For the subject to appear as the originarily synthetic unity of the conditions of objectivity (of “experience”), first, the cogito must be reformulated not only as reflexivity, but as the thesis of the “I think” that “accompanies all my representations” (that is, as the thesis of self-consciousness, which Heidegger will state as: cogito = cogito me cogitare); then this self-consciousness must be distinguished both from the intuition of an intelligible being and from the intuition of the “empirical ego” in “internal sense”; and finally, “the paralogism of the substantiality” of the soul must be dissolved. In other words, one and the same historico-philosophical operation discovers the subject in the substance of the Cartesian cogito, and denounces the substance in the subject (as transcendental illusion), thus installing Descartes in the situation of a “transition” (both ahead of and behind the time of history, conceived of as the history of the advent of the subject), upon which the philosophies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries will not cease to comment.

Paraphrasing Kant himself, we can say that these formulations of the Critique of Pure Reason form the “unique text” from which the transcendental philosophies in particular “draw all their wisdom,” for they ceaselessly reiterate the double rejection of substantiality and of phenomenality that forms the paradoxical being of the subject (being/nonbeing, in any case not a thing, not “categorizable,” not “objectifiable”).5 And this is valid not only for the “epistemological” face of the subject, but for its practical face as well: in the last instance the transcendental subject that effectuates the nonsubstantial unity of the conditions of experience is the same as the one that, prescribing its acts to itself in the mode of the categorical imperative, inscribes freedom in nature (it is tempting to say that it exscribes it: Heidegger is an excellent guide on this point), that is, the same as the one identified in a teleological perspective with the humanity of man.

A poster for the 1962 horror movie The Brain who Wouldn’t Die.

A Historical Play on Words

What is the purpose of this gloss, which has been both lengthy and schematic? It is that it is well worth the trouble, in my view, to take seriously the question “Who comes after the subject?” posed by Jean-Luc Nancy, or rather the form that Nancy was able to confer, by a radical simplification, to an otherwise rather diffuse interrogation of what is called the philosophical conjuncture, but on the condition of taking it quite literally—at the risk of getting tangled up in it. Not everyone is capable of producing a truly sophistic question, that is, one able to confront philosophy, in the medium of a given language, with the aporia of its own “founding” reflection, with the circularity of its enunciation. It is thus with the necessity and impossibility of a “decision” on which the progress of its discourse depends. With this little phrase, “Who comes after the subject?” Nancy seems to have managed the trick, for the only possible “answer”—at the same level of generality and singularity—would designate the nonsubject, whatever it may be, as “what” succeeds the subject (and thus puts an end to it). The place to which it should come, however, is already determined as the place of a subject by the question “who,” in other words as the being (who is the) subject and nothing else. And our “subject” (which is to say unavoidably ourselves, whoever we may be or believe ourselves to be, caught in the constraints of the statement) is left to ask indefinitely, “How could it be that this (not) come of me?” Let us rather examine what characterizes this form.

First of all, the question is posed in the present tense: a present that doubtless refers to what is “current,” and behind which we could 6 reconstitute a whole series of presuppositions about the “epoch” in which we find ourselves: whether we represent it as the triumph of subjectivity or as its dissolution, as an epoch that is still progressing or as one that is coming to an end (and thus in a sense has already been left behind). Unless, precisely, these alternatives are among the preformulations whose apparent obviousness would be suspended by Nancy’s question. But there is another way to interpret such a present tense: as an indeterminate, if not ahistorical present, with respect to which we would not (at least not immediately) have to situate ourselves by means of a characterization of “our epoch” and its meaning, but which would only require us to ask what comes to pass when it comes after the subject, at whatever time this “event” may take place or might have taken place. This is the point of view I have chosen, for reasons that will soon become clear.

Second, the question posed is “Who comes … ?” Here again, two understandings are possible. The first, which I sketched out a moment ago, is perhaps more natural to the contemporary philosopher. Beginning from a pre-comprehension of the subject such as it is constituted by transcendental philosophy (das Subjekt), and such as it has since been deconstructed or decentered by different philosophies “of suspicion,” different “structural” analyses, this understanding opens upon the enigma into which the personality of the subject leads us: the fact that it always succeeds itself across different philosophical figures or different modes of (re)presentation—which is perhaps only the mirror repetition of the way in which it always precedes itself (question: Who comes before the subject?). But why not follow more fully the indication given by language? If a question of identity is presupposed by Nancy’s question, it is not of the form “What is the subject?” (or “What is the thing that we call the subject?”), but of the form “Who is the subject?,” or even as an absolute precondition: “Who is subject?” The question is not about the subjectum but about the subjectus, he who is subjected. Not, or at least not immediately, the transcendental subject (with all its doubles: logical subject, grammatical subject, substantial subject), which is by definition a neuter (before becoming an it), but the subject as an individual or a person submitted to the exercise of a power, whose model is, first of all, political, and whose concept is juridical. Not the subject inasmuch as it is opposed to the predicate or object, but the one referred to by Bossuet’s thesis: “All men are born subjects and the paternal authority that accustoms them to obeying accustoms them at the same time to having only one chief.”7

The French (or Anglo-French) language here presents an advantage over German or even over Latin, one that is properly philosophical: it retains in the equivocal unity of a single noun the subjectum and the subjectus, the Subjekt and the Untertan. It is perhaps for lack of having paid attention to what such a continuity indicates that Heidegger proposed a fictive interpretation of the history of metaphysics in which the anteriority of the question of the subjectus/Untertan is “forgotten” and covered over by a retrospective projection of the question of the Subjekt as subjectum. This presentation, which marks the culmination of a long enterprise of interiorization of the history of philosophy, is today sufficiently widely accepted, even by philosophers who would not want to be called “Heideggerians” (and who often do not have the knowledge Heidegger had), for it to be useful to situate exactly the moment of forcing.

But if this is what the subject is from the first (both historically and logically), then the answer to Nancy’s question is very simple, but so full of consequences that it might be asked whether it does not underlie every other interpretation, every reopening of the question of the subject, including the subject as transcendental subject. Here is the answer: After the subject comes the citizen. The citizen (defined by his rights and duties) is that “nonsubject” who comes after the subject, and whose constitution and recognition put an end (in principle) to the subjection of the subject.

This answer does not have to be (fictively) discovered, or proposed as an eschatological wager (supposing that the subject is in decline, what can be said of his future successor?). It is already given and in all our memories. We can even give it a date: 1789, even if we know that this date and the pace it indicates are too simple to enclose the entire process of the substitution of the citizen for the subject. The fact remains that 1789 marks the irreversibility of this process—the effect of a rupture.

We also know that this answer carries with it, historically, its own justification: If the citizen comes after the subject, it is in the quality of a rehabilitation, even a restoration (implied by the very idea of a revolution). The subject is not the original man, and, contrary to Bossuet’s thesis, men are not “born” “subjects” but “free and equal in rights.” The factual answer, which we already have at hand (and about which it is tempting to ask why it must be periodically suspended, in the game of a question that inverts it) also contains the entire difficulty of an interpretation that makes the “subject” a nonoriginary given, a beginning that is not (and cannot be) an origin. For the origin is not the subject, but man. But is this interpretation the only possible one? Is it indissociable from the fact itself? I would like to devote a few provisional reflections to the interest that these questions hold for philosophy—including when philosophy is displaced from the subjectus to the subjectum.

These reflections do not tend—as will quickly be apparent—to minimize the change produced by Kant, but to ask precisely in what the necessity of this change resides, and if it is truly impossible to bypass or go beyond (and thus to understand) it—in other words, if a critique of the representation of the history of philosophy that we have inherited from Kant can only be made from the point of view of a “subject” in the Kantian sense. The answer seems to me to reside at least partially in the analysis of this “coincidence”: the moment in which Kant produces (and retrospectively projects) the transcendental “subject” is precisely that moment at which politics destroys the “subject” of the prince, in order to replace him with the republican citizen.

That this isn’t really a coincidence is already hinted at by the fact that the question of the subject, around which the Copernican revolution pivots, is immediately characterized as a question of right (as to knowledge and as to action). In this question of right, the representation of “man,” about whom we have just noted that he forms the teleological horizon of the subject, vacillates. What is to be found under this name is not de facto man, subjected to various internal and external powers, but de jure man (who could still be called the man of man or the man in man, and who is also the empirical nonman), whose autonomy corresponds to the position of a “universal legislator.” Which, to be brief, brings us back to the answer evoked above: after the subject (subjectus) comes the citizen. But is this citizen immediately what Kant will name “subject” (Subjekt)? Or is not the latter rather the reinscription of the citizen in a philosophical and, beyond that, anthropological space, which evokes the defunct subject or the prince even while displacing it? We cannot respond directly to these questions, which are inevitably raised by the letter of the Kantian invention once the context of its moment is restored. We must first make a detour through history. Who is the subject of the prince? And who is the citizen who comes after the subject?

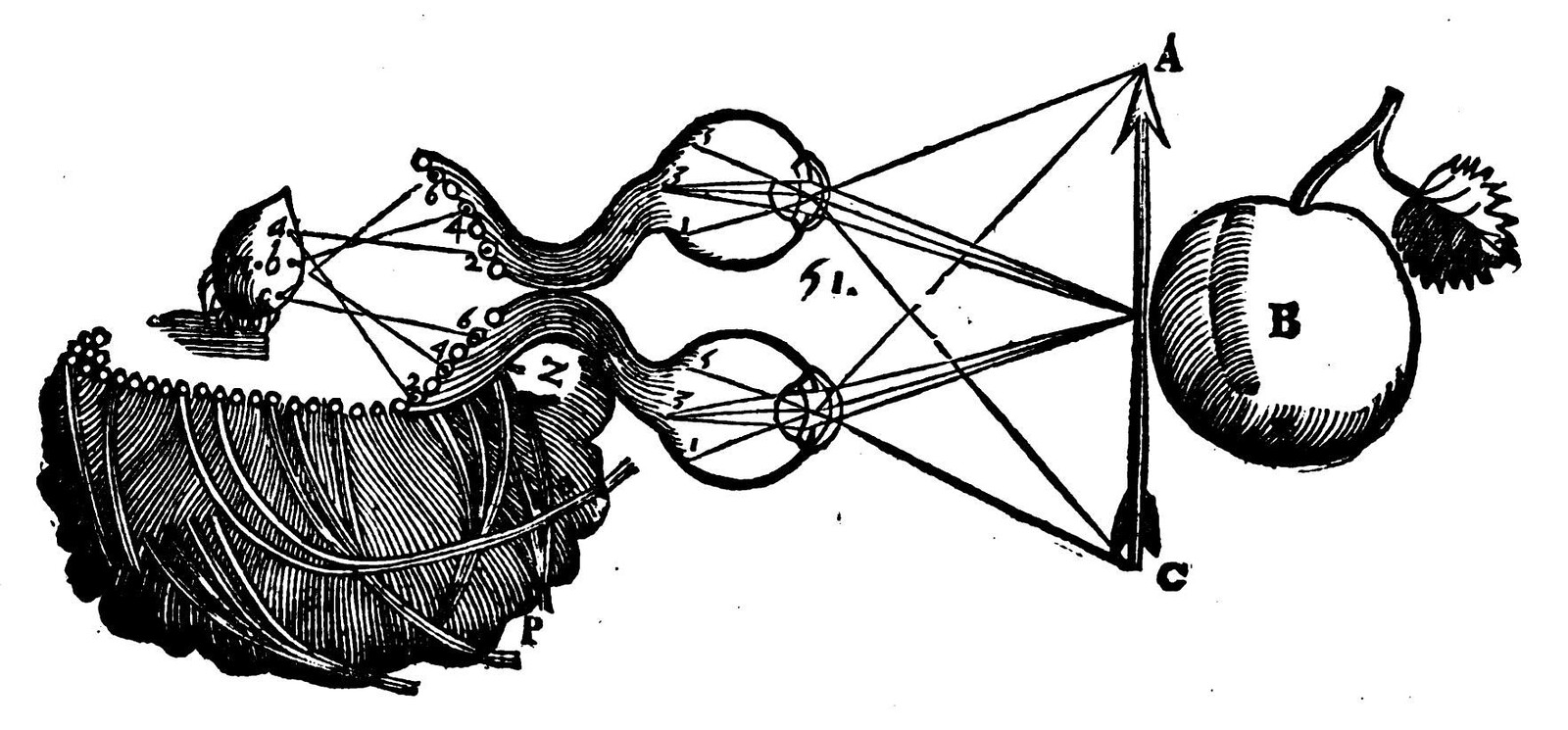

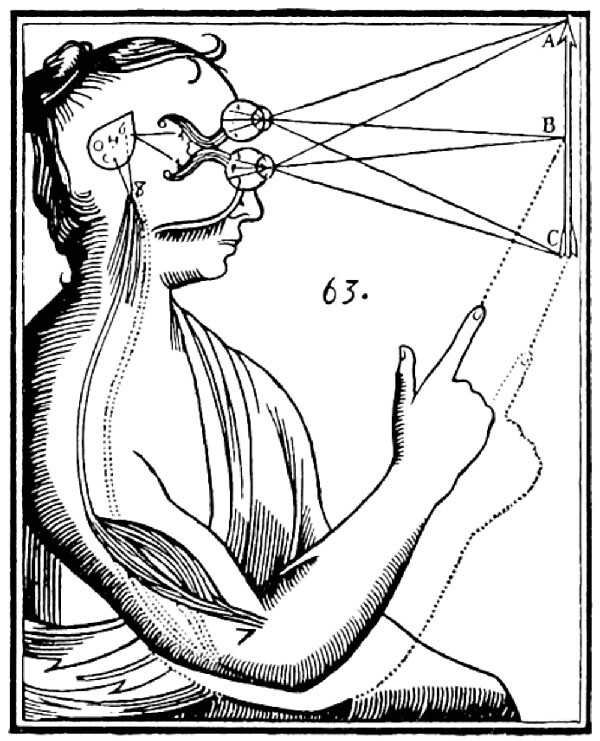

René Descartes’ idea of vision, 1692. The passage of nervous impulses from the eye to the pineal gland and so to the muscles. From Rene Descartes’ Opera Philosophica (Tractatus de homine), 1692.

The Subject of Obedience

It would be impossible to enclose the “subjectus” in a single definition, for it is a matter of a juridical figure whose evolution is spread out over seventeen countries, from Roman jurisprudence to absolute monarchy. It has often been demonstrated how, in the political history of Western Europe, the time of subjects coincides with that of absolutism. Absolutism, in effect, seems to give a complete and coherent form to a power that is founded only upon itself, and that is founded as being without limits (thus uncontrollable and irresistible by definition). Such a power truly makes men into subjects, and nothing but subjects, for the very being of the subject is obedience. From the point of view of the subject, power’s claim to incarnate both the good and the true is entirely justified: the subject is he who has no need of knowing, much less understanding, why what is prescribed to him is in the interest of his own happiness. Nevertheless, this perspective is deceptive: rather than a coherent from, classical absolutism is a knot of contradictions, and this can also be seen at the level of theory, in its discourse. Absolutism never manages to stabilize its definition of obedience and thus its definition of the subject. It could be asked why this is necessarily the case, and what consequences result from it for the “surpassing” or “negation” of the subject in the citizen (if we should ever speak of sublation (relève) it is now: the citizen is a subject who rises up (qui se relève)!). In order to answer this question we must sketch a historical genesis of the subject and his contradiction.

The first question would be to know how one moves from the adjective to the substantive, from individuals who are subjected to the power of another, to the representation of a people or of a community as a set of “subjects.” The distinction between independent and dependent persons is fundamental in Roman jurisprudence. A single text will suffice to recall it:

Sequitur de jure personarum alia divisio. Nam quaedam personae juris sunt, quaedam alieno juri sunt subjectae. Sed rursus earum personarum quae alieno juri subjectae sunt, aliae in potestate, aliae in manum, aliae in manci pio sunt. Videamus nunc de iis quae alieno juri subjectae sint, si cognoverimus quae istae personae sunt, simul intellegemus quae sui juris sint.

We come to another classification in the law of persons. Some people are independent and some are subject to others. Again, of those persons who are dependent, some are in power, some in marital subordination and some in bondage. Let us examine the dependent category. If we find out who is dependent, we cannot help seeing who is independent.8

Strangely, it is by way of the definition (the dialectical division) of the forms of subjection that the definition of free men, the masters, is obtained a contrario. But this definition does not make the subjects into a collectivity; it establishes no “link” among them. The notions of potestas, manus, and mancipium are not sufficient to do this. The subjects are not the heterogeneous set formed by slaves, plus legitimate children, plus wives, plus acquired or adopted relatives. What is required is an imperium. Subjects thus appeared with the empire (and in relation to the person of the emperor, to whom the citizens and many noncitizens owe “service,” officium). But I would surmise that this necessary condition is not a sufficient one: Romans still had to be able to be submitted to the imperium in the same way (if they ever were) as conquered populations, “subjects of the Roman people” (a confusion that points, contradictorily, toward the horizon of the generalization of Roman citizenship as a personal status in the empire).9 And, above all, the imperium had to be theologically founded as a Christian imperium, a power that comes from God and is conserved by Him.10

In effect, the subject has two major characteristics, both of which lead to aporias (in particular in the form given them by absolute monarchy): he is a subditus; he is not a servus. These characteristics are reciprocal, but each has its own dialectic.

The subject is a subditus: This means that he enters into a relation of obedience. Obedience is not the same as a compulsion: it is something more. It is established not only between a chief who has the power to compel and those who must submit to his power, but between a sublimis, “chosen” to command, and subditi, who turn towards him to hear a law. The power to compel is distributed throughout a hierarchy of unequal powers (relations of majoritas minoritas). Obedience is the principle, identical to itself along the whole length of the hierarchical chain, and attached in the last instance to its transcendental origin, which makes those who obey into the members of a single body. Obedience institutes the command of higher over lower, but it fundamentally comes from below: as subditi, the subjects will their own obedience. And if they will it, it is because it is inscribed in an economy of creation (their creation) and salvation (their salvation, that of each taken individually and of all taken collectively). Thus the loyal subject (fidèle sujet) (he who “voluntarily,” “loyally,” that is, actively and willingly obeys the law and executes the orders of a legitimate sovereign) is necessarily a faithful subject (sujet fidèle). He is a Christian, who knows that all power comes from God. In obeying the law of the prince he obeys God.11 The fact that the order to which he “responds” comes to him from beyond the individual and the mouth that utters it is constitutive of the subject.

This structure contains the seeds of an infinite dialectic, which is in fact what unifies the subject (in the same way as it unifies, in the person of the sovereign, the act and its sanctification, decision making and justice): because of it the subject does not have to ask (himself) any questions, for the answers have always already been given. But it is also what divides the subject. This occurs, for example, when a “spiritual power” and a “temporal power” vie for preeminence (which supposes that each also attempts to appropriate the attributes of the other), or, more simply, when knowing which sovereign is legitimate or which practice of government is “Christian” and thus, in conformity with its essence, becomes a real question (the very idea of a “right of resistance” being a contradiction in terms, the choice is between regicide and prayer for the conversion of the sovereign … ). Absolute monarchy in particular develops a contradiction that can be seen as the culmination of the conflict between the temporal power and the spiritual power. A passage is made from the divine right of kings to the idea of their direct election: It is as such that royal power is made divine (and that the State transfers to itself the various sacraments). But not (at least not in the West) the individual person of the king: incarnation of a divine power, the king is not himself “God.” The king (the sovereign) is lex animata (nomos empsychos) (just as the law is inanimatus princeps). Thus the person (the “body”) of the king must itself be divided: into divine person and human person. And obedience correlatively … 12

Such an obedience, in its unity and its divisions, implies the notion of the soul. This is a notion that Antiquity did not know or in any case did not use in the same way in order to think a political relation (Greek does not have, to my knowledge, an equivalent for the subjectus subditus, not even the term hypekoos, which designates those who obey the word of a master, who will become “disciples,” and from whom the theologians will draw the same of Christian obedience: hypakoè). For Antiquity obedience can be a contingent situation in which one finds oneself in relation to a command (archè), and thus a commander (Archon). But to receive a command (archemenos) implies that one can oneself—at least theoretically—give a command (this is the Aristotelian definition of the citizen). Or it can be a natural dependence of the “familial” type. Doubtless differentiations (the ignorance of which is what properly characterizes barbarism) ought to be made here: the woman (even for the Greeks, and a fortiori for the Romans) is not a slave. Nevertheless, these differences can be subsumed under analogous oppositions: the part and the whole, passivity and activity, the body and the soul (or intellect). This last opposition is particularly valid for the slave, who is to his master what a body, an “organism” (a set of natural tools) is to intelligence. In such a perspective, the very idea of a “free obedience” is a contradiction in terms. That a slave can also be free is a relatively late (Stoic) idea, which must be understood as signifying that on another level (in a “cosmic” polity, a polity of “minds”) he who is a slave here can also be a master (master of himself, of his passions), can also be a “citizen.” Nothing approaches the idea of a freedom residing in obedience itself, resulting from this obedience. In order to conceive of this idea, obedience must be transferred to the side of the soul, and the soul must cease to be thought of as natural. On the contrary, the soul must come to name a supernatural part of the individual that hears the dignity of the order.

Thus the subditus-subjectus has always been distinguished from the slave, just as the sovereignty of the prince, the sublimus, has been distinguished from “despotism” (literally, the authority of a master of slaves).13 But this fundamental distinction was elaborated in two ways. It was elaborated within a theological framework, simply developing the idea that the subject is a believer, a Christian. Because, in the final instance, it is his soul that obeys, he could never be the sovereign’s “thing” (which can be used and abused); his obedience is inscribed in an order that should, in the end, bring him salvation, and that is counterbalanced by a responsibility (a duty) on the part of the prince. But this way of thinking the freedom of the subject is, in practice, extraordinarily ambivalent. It can be understood either as the affirmation and the active contribution of his will to obedience (just as the Christian, by his works, “cooperates in his salvation”: the political necessity of the theological compromise on the question of predestination can be seen here), or as the annihilation of the will (this is why the mystics who lean toward perfect obedience apply their will to self-annihilation in the contemplation of God, the only absolute sovereign). Intellectual reasons as well as material interests (those of the lords, of the corporations, of the “bourgeois” towns) provide an incentive for thinking the freedom of the subject differently, paradoxically combining the concept with that of the “citizen,” a concept taken from Antiquity and notably from Aristotle, but carefully distinguished from man inasmuch as he is the image of the creator.

Thus the civis polites comes back onto the scene, in order to make the quasi-ontological difference between a “subject” and a serf/slave. But the man designated as a citizen is no longer the zoon politikon: he is no longer the “sociable animal,” meaning that he is sociable as an animal (and not inasmuch as his soul is immortal). Thomas Aquinas distinguishes the (supernatural) christianitas of man from his (natural) humanitas, the “believer” from the “citizen.” The latter is the holder of a neutral freedom, a “franchise.” This has nothing in common with sovereignty, but means that his submission to political authority is neither immediate nor arbitrary. He is submitted as a member of an order or a body that is recognized as having certain rights and that confers a certain status, a field of initiative, upon him. What then becomes of the “subject”? In a sense, he is more really free (for his subjection is the effect of a political order that integrates “civility,” the “polity,” and that is thus inscribed in nature). But it becomes more and more difficult to think him as subditus: the very concept of his “obedience” is menaced.

The tension becomes, once again, a contradiction under absolute monarchy. We have already seen how the latter brings the mysterious unity of the temporal and spiritual sovereign to the point of rupture. The same goes for the freedom of the subject. Insofar as absolute monarchy concentrates power in the unity of the “State” (the term appears at this moment, along with “reason”) and suppresses all subjections to the profit of one subjection. There is now only one prince, whose law is will, “father of his subjects,” having absolute authority over them (as all other authority, next to his, is null). “I am the State,” Louis XIV will say. But absolute monarchy is a State power, precisely, that is, a power that is instituted and exercised by law and administration; it is a political power (imperium) that is not confused with the property (dominium)—except “eminent” domain—of what belongs to individuals, and over which they exercise their power. The subjects are, if not “legal subjects (sujets de droit),” at least subjects “with rights (en droit),” members of a “republic” (a Commonwealth, Hobbes will say). All the theoreticians of absolute monarchy (with or without a “pact of subjection”) will explain that the subjects are citizens (or, like Bodin in the Republic, that “every citizen is a subject, his freedom being somewhat diminished by the majesty of the one to whom he owes obedience; but not every subject is a citizen, as we have said of the slave”).14 They will not prevent—with the help of circumstances—the condition of this “free (franc) subject dependent upon the sovereignty of another”15 from being perceived as untenable. La Boétie, reversing each term, will oppose them by defining the power of the One (read: the Monarch) as a “voluntary servitude” upon which at the same time reason of State no longer confers the meaning of a supernatural freedom. The controversy over the difference (or lack of one) between absolutism and despotism accompanies the whole history of absolute monarchy.16 The condition of subject will be retrospectively identified with that of the slave, and subjection with “slavery,” from the point of view of the new citizen and his revolution (this will also be an essential mechanism of his own idealization).

This excerpt is the first half of the introductory essay for Balibar’s Citizen Subject, which is published this month in English by Fordham University press.

Letter by Descartes to Christine, 3 November 1645, Oeuvres de Descartes, ed. Charles Adam and Paul Tannery (Paris: J. Vrin, 1969), 4:333. Cited by Jean-Luc Marion, Sur la théologie blanche de Descartes (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1981), 411.

Oeuvres de Descartes, 1: 145.

I am aware that is a matter of opposing them: but in order to oppose them directly, as the recto and verso, the permanence of a single question (of a single “opening”) must be supposed, beyond the question of the subjectus, which falls into the ashcan of the “history of being.”

Applying it to Kant himself if need be: for the fate of this problematic—by the very fact that the transcendental subject is a limit, even the limit as such, declared to be constitutive is to observe that there always remains some substance or some phenomenality in that it must be reduced.

As Nancy himself suggests in the considerations of his letter of invitation, from which I reproduce a key passage: “This question can be explained as follows: one of the major characteristics of contemporary thought is the putting into question of the instance of the ‘subject,’ according to the structure, the meaning, and the value subsumed under this term in modern thought from Descartes to Hegel, if not to Husserl. The inaugurating decisions of contemporary thought … have all involved putting subjectivity on trial. A widespread discourse of recent date proclaimed the subject’s simple liquidation. Everything seems, however, to point to the necessity, not of a ‘return to the subject’ … but on the contrary, of a move forward toward someone—some one—else in his place (this last expression is obviously a mere convenience: the ‘place’ could not be the same).Who would it be? How would s/he present him/herself? Can we name him/her? Is the question ‘who’ suitable? … In other words: If it is appropriate to assign something like a punctuality, a singularity, or a hereness (haecceitas) as the place of emission, reception, or transition (or affect, of action, of language, etc.), how would one designate its specificity? Or would the question need to be transformed—or is it in fact out of place to ask it?” Jean-Luc Nancy, Who Comes After the Subject?, 5.

Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Politique tirée de des propres paroles de l’Écriture sainte, ed. Jacques Le Brun (Geneva: Droz, 1967), 53. Bossuet states: “All men are born subjects.” Descartes says: There are innate ideas, which God has always already planted in my soul, as seeds of truth, whose nature (that of being eternal truths) is contemporaneous with my nature (for God creates or conserves them at every moment just as he creates or conserves me), and which at bottom are entirely enveloped in the infinity of that envelops all my true ideas, beginning with the first: my thinking existence.

The Institutes of Gaius, trans. W. M. Gordon and O. F. Robinson (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., Ltd., 1988), §48, 45.

See Christian Bruschi, “Le droit de cité dans l’Antiquité: Un questionnement pour la citoyenneté aujourd’hui,” in La citoyenneté et les changements de structures sociales et nationales de la population française, ed. Catherine Wihtol de Wenden, 125–153 (n.p.: Edilig/Fondation Diderot, 1988).

Emmanuel Terray suggests to me that this is one of the reasons for Constantine’s rallying to Pauline Christianity (“All power comes from God”: see Epistle to the Romans).

On all of these points, see, for example, Walter Ullman, The Individual and Society in the Middle Ages (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1966), and A History of Political Thought: The Middle Ages (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1965).

On all this, see Ernst Kantorowicz, Frederick the Second, 1194–1250, trans. E. O. Lorimer (New York: Ungar, 1957); The King’s Two Bodies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960); Selected Studies (New York: J. J. Augustin, 1965).

How does one get from the Roman servus to the medieval serf? Doubtless by a change in the “mode of production” (even though it is doubtless that, from the strict point of view of production, each of these terms corresponds to a single mode). But this change presupposes or implies that the “serf” also has an immortal soul included in the economy of salvation; this is why he is attached to the land rather than to the master.

Jean Bodin, Les six livres de la République, vol. 1, §6 (Paris: Fayard, 1986), 114.

Ibid., 1:112.

See Alain Grosrichard, The Sultan’s Court: European Fantasies of the East, trans. Liz Heron, intro. Mladen Dolar (New York: Verso, 1998).

This essay was first published in English as “Citizen Subject,” in Who Comes after the Subject? ed. Eduardo Cadava, Peter Connor, and Jean-Luc Nancy (New York: Routledge, 1991), 33–57. Copyright 1991. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, a division of Informa plc. Translated by James Swenson