We are all lichens.

— Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now”1Think we must. We must think.

—Stengers and Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss2

What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Biological sciences have been especially potent in fermenting notions about all the mortal inhabitants of the Earth since the imperializing eighteenth century. Homo sapiens — the Human as species, the Anthropos as the human species,Modern Man — was a chief product of these knowledge practices. What happens when the best biologies of the twenty-first century cannot do their job with bounded individuals plus contexts, when organisms plus environments, or genes plus whatever they need, no longer sustain the overflowing richness of biological knowledges, if they ever did? What happens when organisms plus environments can hardly be remembered for the same reasons that even Western-indebted people can no longer figure themselves as individuals and societies of individuals in human-only histories? Surely such a transformative time on Earth must not be named the Anthropocene!

With all the unfaithful offspring of the sky gods, with my littermates who find a rich wallow in multispecies muddles, I want to make a critical and joyful fuss about these matters. I want to stay with the trouble, and the only way I know to do that is in generative joy, terror, and collective thinking.

My first demon familiar in this task will be a spider, Pimoa cthulhu, who lives under stumps in the redwood forests of Sonoma and Mendocino Counties, near where I live in North Central California.3 Nobody lives everywhere; everybody lives somewhere. Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something.4 This spider is in place, has a place, and yet is named for intriguing travels elsewhere. This spider will help me with returns, and with roots and routes.5 The eight-legged tentacular arachnid that I appeal to gets her generic name from the language of the Goshute people of Utah and her specific name from denizens of the depths, from the abyssal and elemental entities, called chthonic.6 The chthonic powers of Terra infuse its tissues everywhere, despite the civilizing efforts of the agents of sky gods to astralize them and set up chief Singletons and their tame committees of multiples or subgods, the One and the Many. Making a small change in the biologist’s taxonomic spelling, from cthulhu to chthulu, with renamed Pimoa chthulu I propose a name for an elsewhere and elsewhen that was, still is,and might yet be: the Chthulucene. I remember that tentacle comes from the Latin tentaculum, meaning “feeler,” and tentare, meaning “to feel” and “to try”; and I know that my leggy spider has many-armed allies. Myriad tentacles will be needed to tell the story of the Chthulucene.7

The tentacular are not disembodied figures; they are cnidarians, spiders, fingery beings like humans and raccoons, squid, jellyfish, neural extravaganzas, fibrous entities, flagellated beings, myofibril braids, matted and felted microbial and fungal tangles, probing creepers, swelling roots, reaching and climbing tendrilled ones. The tentacular are also nets and networks, it critters, in and out of clouds. Tentacularity is about life lived along lines — and such a wealth of lines — not at points, not in spheres. “The inhabitants of the world, creatures of all kinds, human and non-human, are wayfarers”; generations are like “a series of interlaced trails.”8

All the tentacular stringy ones have made me unhappy with posthumanism, even as I am nourished by much generative work done under that sign. My partner Rusten Hogness suggested compost instead of posthuman(ism), as well as humusities instead of humanities, and I jumped into that wormy pile.9 Human as humus has potential, if we could chop and shred human as Homo, the detumescing project of a self-making and planet-destroying CEO. Imagine a conference not on the Future of the Humanities in the Capitalist Restructuring University, but instead on the Power of the Humusities for a Habitable Multispecies Muddle! Ecosexual artists Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle made a bumper sticker for me, for us, for SF: “Composting is so hot!”

Shaping her thinking about the times called Anthropocene and “multi-faced Gaïa” (Stengers’s term) in companionable friction with Latour, Isabelle Stengers does not ask that we recompose ourselves to become able, perhaps, to “face Gaïa.” But like Latour and even more like Le Guin, one of her most generative SF writers, Stengers is adamant about changing the story. Focusing on intrusion rather than composition, Stengers calls Gaia a fearful and devastating power that intrudes on our categories of thought, that intrudes on thinking itself.10 Earth/Gaia is maker and destroyer, not resource to be exploited or ward to be protected or nursing mother promising nourishment. Gaia is not a person but complex systemic phenomena that compose a living planet. Gaia’s intrusion into our affairs is a radically materialist event that collects up multitudes. This intrusion threatens not life on Earth itself — microbes will adapt, to put it mildly — but threatens the livability of Earth for vast kinds, species, assemblages, and individuals in an “event” already under way called the Sixth Great Extinction.11

Stengers, like Bruno Latour, evokes the name of Gaia in the way James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis did, to name complex nonlinear couplings between processes that compose and sustain entwined but nonadditive subsystems as a partially cohering systemic whole.12 In this hypothesis, Gaia is autopoietic — self-forming, boundary maintaining, contingent, dynamic, and stable under some conditions but not others. Gaia is not reducible to the sum of its parts, but achieves finite systemic coherence in the face of perturbations within parameters that are themselves responsive to dynamic systemic processes. Gaia does not and could not care about human or other biological beings’ intentions or desires or needs, but Gaia puts into question our very existence, we who have provoked its brutal mutation that threatens both human and nonhuman livable presents and futures. Gaia is not about a list of questions waiting for rational policies;13 Gaia is an intrusive event that undoes thinking as usual. “She is what specifically questions the tales and refrains of modern history. There is only one real mystery at stake, here: it is the answer we, meaning those who belong to this history, may be able to create as we face the consequences of what we have provoked.”14

Anthropocene

So, what have we provoked? Writing in the midst of California’s historic multiyear drought and the explosive fire season of 2015, I need the photograph of a fire set deliberately in June 2009 by Sustainable Resource Alberta near the Saskatchewan River Crossing on the Icefields Parkway in order to stem the spread of mountain pine beetles, to create a fire barrier to future fires, and to enhance biodiversity. The hope is that this fire acts as an ally for resurgence. The devastating spread of the pine beetle across the North American West is a major chapter of climate change in the Anthropocene. So too are the predicted megadroughts and the extreme and extended fire seasons. Fire in the North American West has a complicated multispecies history; fire is an essential element for ongoing, as well as an agent of double death, the killing of ongoingness. The material semiotics of fire in our times are at stake.

Thus it is past time to turn directly to the time-space-global thing called Anthropocene.15 The term seems to have been coined in the early 1980s by University of Michigan ecologist Eugene Stoermer (d. 2012), an expert in freshwater diatoms. He introduced the term to refer to growing evidence for the transformative effects of human activities on the Earth. The name Anthropocene made a dramatic star appearance in globalizing discourses in 2000 when the Dutch Nobel Prize – winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen joined Stoermer to propose that human activities had been of such a kind and magnitude as to merit the use of a new geological term for a new epoch, superseding the Holocene, which dated from the end of the last ice age, or the end of the Pleistocene, about twelve thousand years ago. Anthropogenic changes signaled by the mid-eighteenth-century steam engine and the planet-changing exploding use of coal were evident in the airs, waters, and rocks.16 Evidence was mounting that the acidification and warming of the oceans are rapidly decomposing coral reef ecosystems, resulting in huge ghostly white skeletons of bleached and dead or dying coral. That a symbiotic system — coral, with its watery world-making associations of cnidarians and zooanthellae with many other critters too — indicated such a global transformation will come back into our story.

But for now, notice that the Anthropocene obtained purchase in popular and scientific discourse in the context of ubiquitous urgent efforts to find ways of talking about, theorizing, modeling, and managing a Big Thing called Globalization. Climate-change modeling is a powerful positive feedback loop provoking change-of-state in systems of political and ecological discourses.17 That Paul Crutzen was both a Nobel laureate and an atmospheric chemist mattered. By 2008, many scientists around the world had adopted the not-yet-official but increasingly indispensable term;18 and myriad research projects, performances, installations, and conferences in the arts, social sciences, and humanities found the term mandatory in their naming and thinking, not least for facing both accelerating extinctions across all biological taxa and also multispecies, including human, immiseration across the expanse of Terra. Fossil-burning human beings seem intent on making as many new fossils as possible as fast as possible. They will be read in the strata of the rocks on the land and under the waters by the geologists of the very near future, if not already. Perhaps, instead of the fiery forest, the icon for the Anthropocene should be Burning Man!19

The scale of burning ambitions of fossil-making man — of this Anthropos whose hot projects for accelerating extinctions merits a name for a geological epoch — is hard to comprehend. Leaving aside all the other accelerating extractions of minerals, plant and animal flesh, human homelands, and so on, surely, we want to say, the pace of development of renewable energy technologies and of political and technical carbon pollution-abatement measures, in the face of palpable and costly ecosystem collapses and spreading political disorders, will mitigate, if not eliminate, the burden of planet-warming excess carbon from burning still more fossil fuels. Or, maybe the financial troubles of the global coal and oil industries by 2015 would stop the madness. Not so. Even casual acquaintance with the daily news erodes such hopes, but the trouble is worse than what even a close reader of IPCC documents and the press will find. In “The Third Carbon Age,” Michael Klare, a professor of Peace and World Security Studies at Hampshire College, lays out strong evidence against the idea that the old age of coal, replaced by the recent age of oil, will be replaced by the age of renewables.20 He details the large and growing global national and corporate investments in renewables; clearly, there are big profit and power advantages to be had in this sector. And at the same time, every imaginable, and many unimaginable, technologies and strategic measures are being pursued by all the big global players to extract every last calorie of fossil carbon, at whatever depth and in whatever formations of sand, mud, or rock, and with whatever horrors of travel to distribution and use points, to burn before someone else gets at that calorie and burns it first in the great prick story of the first and the last beautiful words and weapons.21 In what he calls the Age of Unconventional Oil and Gas, hydrofracking is the tip of the (melting) iceberg. Melting of the polar seas, terrible for polar bears and for coastal peoples, is very good for big competitive military, exploration, drilling, and tanker shipping across the northern passages. Who needs an ice-breaker when you can count on melting ice?22

A complex systems engineer named Brad Werner addressed a session at the meetings of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco in 2012. His point was quite simple: scientifically speaking, global capitalism “has made the depletion of resources so rapid, convenient and barrier-free that ‘earth-human systems’ are becoming dangerously unstable in response.” Therefore, he argued, the only scientific thing to do is revolt! Movements, not just individuals, are critical. What is required is action and thinking that do not fit within the dominant capitalist culture; and, said Werner, this is a matter not of opinion, but of geophysical dynamics. The reporter who covered this session summed up Werner’s address: “He is saying that his research shows that our entire economic paradigm is a threat to ecological stability.”23 Werner is not the first or the last researcher and maker of matters of concern to argue this point, but his clarity at a scientific meeting is bracing. Revolt! Think we must; we must think. Actually think, not like Eichmann the Thoughtless. Of course, the devil is in the details — how to revolt? How to matter and not just want to matter?

Capitalocene

But at least one thing is crystal clear. No matter how much he might be caught in the generic masculine universal and how much he only looks up, the Anthropos did not do this fracking thing and he should not name this double-death-loving epoch. The Anthropos is not Burning Man after all. But because the word is already well entrenched and seems less controversial to many important players compared to the Capitalocene, I know that we will continue to need the term “Anthropocene.” I will use it too, sparingly; what and whom the Anthropocene collects in its refurbished netbag might prove potent for living in the ruins and even for modest terran recuperation.

Still, if we could only have one word for these SF times, surely it must be the Capitalocene.24

Species Man did not shape the conditions for the Third Carbon Age or the Nuclear Age. The story of Species Man as the agent of the Anthropocene is an almost laughable rerun of the great phallic humanizing and modernizing Adventure, where man, made in the image of a vanished god, takes on superpowers in his secular-sacred ascent, only to end in tragic detumescence, once again. Autopoietic, self-making man came down once again, this time in tragic system failure, turning biodiverse ecosystems into flipped-out deserts of slimy mats and stinging jellyfish. Neither did technological determinism produce the Third Carbon Age. Coal and the steam engine did not determine the story, and besides the dates are all wrong, not because one has to go back to the last ice age, but because one has to at least include the great market and commodity reworldings of the long sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the current era, even if we think (wrongly) that we can remain Euro-centered in thinking about “globalizing” transformations shaping the Capitalocene.25 One must surely tell of the networks of sugar, precious metals, plantations, indigenous genocides, and slavery, with their labor innovations and relocations and recompositions of critters and things sweeping up both human and nonhuman workers of all kinds. The infectious industrial revolution of England mattered hugely, but it is only one player in planet-transforming, historically situated, new-enough, worlding relations. The relocation of peoples, plants, and animals; the leveling of vast forests; and the violent mining of metals preceded the steam engine; but that is not a warrant for wringing one’s hands about the perfidy of the Anthropos, or of Species Man, or of Man the Hunter.

The systemic stories of the linked metabolisms, articulations, or coproductions (pick your metaphor) of economies and ecologies, of histories and human and nonhuman critters, must be relentlessly opportunistic and contingent. They must also be relentlessly relational, sympoietic, and consequential.26 They are terran, not cosmic or blissed or cursed into outer space. The Capitalocene is terran; it does not have to be the last biodiverse geological epoch that includes our species too. There are so many good stories yet to tell, so many netbags yet to string, and not just by human beings.

As a provocation, let me summarize my objections to the Anthropocene as a tool, story, or epoch to think with:

(1) The myth system associated with the Anthropos is a setup, and the stories end badly. More to the point, they end in double death; they are not about ongoingness. It is hard to tell a good story with such a bad actor. Bad actors need a story, but not the whole story.

(2) Species Man does not make history.

(3) Man plus Tool does not make history. That is the story of History human exceptionalists tell.

(4) That History must give way to geostories, to Gaia stories, to symchthonic stories; terrans do webbed, braided, and tentacular living and dying in sympoietic multispecies string figures; they do not do History.

(5) The human social apparatus of the Anthropocene tends to be top-heavy and bureaucracy prone. Revolt needs other forms of action and other stories for solace, inspiration, and effectiveness.

(6) Despite its reliance on agile computer modeling and autopoietic systems theories, the Anthropocene relies too much on what should be an “unthinkable” theory of relations, namely the old one of bounded utilitarian individualism — preexisting units in competition relations that take up all the air in the atmosphere (except, apparently, carbon dioxide).

(7) The sciences of the Anthropocene are too much contained within restrictive systems theories and within evolutionary theories called the Modern Synthesis, which for all their extraordinary importance have proven unable to think well about sympoiesis, symbiosis, symbiogenesis, development, webbed ecologies, and microbes. That’s a lot of trouble for adequate evolutionary theory.

(8) Anthropocene is a term most easily meaningful and usable by intellectuals in wealthy classes and regions; it is not an idiomatic term for climate, weather, land, care of country, or much else in great swathes of the world, especially but not only among indigenous peoples.

I am aligned with feminist environmentalist Eileen Crist when she writes against the managerial, technocratic, market-and-profit besotted, modernizing, and human-exceptionalist business-as-usual commitments of so much Anthropocene discourse. This discourse is not simply wrong-headed and wrong-hearted in itself; it also saps our capacity for imagining and caring for other worlds, both those that exist precariously now (including those called wilderness, for all the contaminated history of that term in racist settler colonialism) and those we need to bring into being in alliance with other critters, for still possible recuperating pasts, presents, and futures. “Scarcity’s deepening persistence, and the suffering it is auguring for all life, is an artifact of human exceptionalism at every level.” Instead, a humanity with more earthly integrity “invites the priority of our pulling back and scaling down, of welcoming limitationsof our numbers, economies, and habitats for the sake of a higher, more inclusive freedom and quality of life.”27

If Humans live in History and the Earthbound take up their task within the Anthropocene, too many Posthumans (and posthumanists, another gathering altogether) seem to have emigrated to the Anthropocene for my taste. Perhaps my human and nonhuman people are the dreadful Chthonic ones who snake within the tissues of Terrapolis.

Note that insofar as the Capitalocene is told in the idiom of fundamentalist Marxism, with all its trappings of Modernity, Progress, and History, that term is subject to the same or fiercer criticisms. The stories of both the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene teeter constantly on the brink of becoming much Too Big. Marx did better than that, as did Darwin. We can inherit their bravery and capacity to tell big-enough stories without determinism, teleology, and plan.28

Historically situated relational worldings make a mockery both of the binary division of nature and society and of our enslavement to Progress and its evil twin, Modernization. The Capitalocene was relationally made, and not by a secular godlike anthropos, a law of history, the machine itself, or a demon called Modernity. The Capitalocene must be relationally unmade in order to compose in material-semiotic SF patterns and stories something more livable, something Ursula K. Le Guin could be proud of. Shocked anew by our — billions of Earth habitants’, including your and my — ongoing daily assent in practice to this thing called capitalism, Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers note that denunciation has been singularly ineffective, or capitalism would have long ago vanished from the Earth. A dark bewitched commitment to the lure of Progress (and its polar opposite) lashes us to endless infernal alternatives, as if we had no other ways to reworld, reimagine, relive, and reconnect with each other, in multispecies well-being. This explication does not excuse us from doing many important things better; quite the opposite. Pignarre and Stengers affirm on-the-ground collectives capable of inventing new practices of imagination, resistance, revolt, repair, and mourning, and of living and dying well. They remind us that the established disorder is not necessary; another world is not only urgently needed, it is possible, but not if we are ensorcelled in despair, cynicism, or optimism, and the belief/disbelief discourse of Progress.29 Many Marxist critical and cultural theorists, at their best, would agree.30 So would the tentacular ones.31

Chthulucene

Reaching back to generative complex systems approaches by Lovelock and Margulis, Gaia figures the Anthropocene for many contemporary Western thinkers. But an unfurling Gaia is better situated in the Chthulucene, an ongoing temporality that resists figuration and dating and demands myriad names. Arising from Chaos,32 Gaia was and is a powerful intrusive force, in no one’s pocket, no one’s hope for salvation, capable of provoking the late twentieth century’s best autopoietic complex systems thinking that led to recognizing the devastation caused by anthropogenic processes of the last few centuries, a necessary counter to the Euclidean figures and stories of Man.33 Brazilian anthropologists and philosophers Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski exorcise lingering notions that Gaia is confined to the ancient Greeks and subsequent Eurocultures in their refiguring the urgencies of our times in the post-Eurocentric conference “The Thousand Names of Gaia.”34 Names, not faces, not morphs of the same, something else, a thousand somethings else, still telling of linked ongoing generative and destructive worlding and reworlding in this age of the Earth. We need another figure, a thousand names of something else, to erupt out of the Anthropocene into another, big-enough story. Bitten in a California redwood forest by spidery Pimoa chthulhu, I want to propose snaky Medusa and the many unfinished worldings of her antecedents, affiliates, and descendants. Perhaps Medusa, the only mortal Gorgon, can bring us into the holobiomes of Terrapolis and heighten our chances for dashing the twenty-first-century ships of the Heroes on a living coral reef instead of allowing them to suck the last drop of fossil flesh out of dead rock.

The terra-cotta figure of Potnia Theron, the Mistress of the Animals, depicts a winged goddess wearing a split skirt and touching a bird with each hand.35 She is a vivid reminder of the breadth, width, and temporal reach into pasts and futures of chthonic powers in Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds and beyond.36 Potnia Theron is rooted in Minoan and then Mycenean cultures and infuses Greek stories of the Gorgons (especially the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa) and of Artemis. A kind of far-traveling Ur-Medusa, the Lady of the Beasts is a potent link between Crete and India. The winged figure is also called Potnia Melissa, Mistress of the Bees, draped with all their buzzing-stinging-honeyed gifts. Note the acoustic, tactile, and gustatory senses elicited by the Mistress and her sympoietic, more-than-human flesh. The snakes and bees are more like stinging tentacular feelers than like binocular eyes, although these critters see too, in compound-eyed insectile and many-armed optics.

In many incarnations around the world, the winged bee goddesses are very old, and they are much needed now.37 Potnia Theron/Melissa’s snaky locks and Gorgon face tangle her with a diverse kinship of chthonic earthly forces that travel richly in space and time. The Greek word Gorgon translates as dreadful, but perhaps that is an astralized, patriarchal hearing of much more aweful stories and enactments of generation, destruction, and tenacious, ongoing terran finitude. Potnia Theron/Melissa/Medusa give faciality a profound makeover, and that is a blow to modern humanist (including technohumanist) figurations of the forward-looking, sky-gazing Anthropos. Recall that the Greek chthonios means “of, in, or under the Earth and the seas” — a rich terran muddle for SF, science fact, science fiction, speculative feminism, and speculative fabulation. The chthonic ones are precisely not sky gods, not a foundation for the Olympiad, not friends to the Anthropocene or Capitalocene, and definitely not finished. The Earthbound can take heart — as well as action.

The Gorgons are powerful winged chthonic entities without a proper genealogy; their reach is lateral and tentacular; they have no settled lineage and no reliable kind (genre, gender), although they are figured and storied as female. In old versions, the Gorgons twine with the Erinyes (Furies), chthonic underworld powers who avenge crimes against the natural order. In the winged domains, the bird-bodied Harpies carry out these vital functions.38 Now, look again at the birds of Potnia Theron and ask what they do. Are the Harpies their cousins? Around 700 BCE Hesiod imagined the Gorgons as sea demons and gave them sea deities for parents. I read Hesiod’s Theogony as laboring to stabilize a very bumptious queer family. The Gorgons erupt more than emerge; they are intrusive in a sense akin to what Stengers understands by Gaia.

The Gorgons turned men who looked into their living, venomous, snake-encrusted faces into stone. I wonder what might have happened if those men had known how to politely greet the dreadful chthonic ones. I wonder if such manners can still be learned, if there is time to learn now, or if the stratigraphy of the rocks will only register the ends and end of a stony Anthropos.39

Because the deities of the Olympiad identified her as a particularly dangerous enemy to the sky gods’ succession and authority, mortal Medusa is especially interesting for my efforts to propose the Chthulucene as one of the big-enough stories in the netbag for staying with the trouble of our ongoing epoch. I resignify and twist the stories, but no more than the Greeks themselves constantly did.40 The hero Perseus was dispatched to kill Medusa; and with the help of Athena, head-born favorite daughter of Zeus, he cut off the Gorgon’s head and gave it to his accomplice, this virgin goddess of wisdom and war. Putting Medusa’s severed head face-forward on her shield, the Aegis, Athena, as usual, played traitor to the Earthbound; we expect no better from motherless mind children. But great good came of this murder-for-hire, for from Medusa’s dead body came the winged horse Pegasus. Feminists have a special friendship with horses. Who says these stories do not still move us materially?41 And from the blood dripping from Medusa’s severed head came the rocky corals of the western seas, remembered today in the taxonomic names of the Gorgonians, the coral-like sea fans and sea whips, composed in symbioses of tentacular animal cnidarians and photosynthetic algal-like beings called zooanthellae.42

With the corals, we turn definitively away from heady facial representations, no matter how snaky. Even Potnia Theron, Potnia Melissa, and Medusa cannot alone spin out the needed tentacularities. In the tasks of thinking, figuring, and storytelling, the spider of my first pages, Pimoa chthulhu, allies with the decidedly nonvertebrate critters of the seas. Corals align with octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish. Octopuses are called spiders of the seas, not only for their tentacularity, but also for their predatory habits. The tentacular chthonic ones have to eat; they are at table, cum panis, companion species of terra. They are good figures for the luring, beckoning, gorgeous, finite, dangerous precarities of the Chthulucene. This Chthulucene is neither sacred nor secular; this earthly worlding is thoroughly terran, muddled, and mortal — and at stake now.

Mobile, many-armed predators, pulsating through and over the coral reefs, octopuses are called spiders of the sea. And so Pimoa chthulhu and Octopus cyanea meet in the webbed tales of the Chthulucene.43

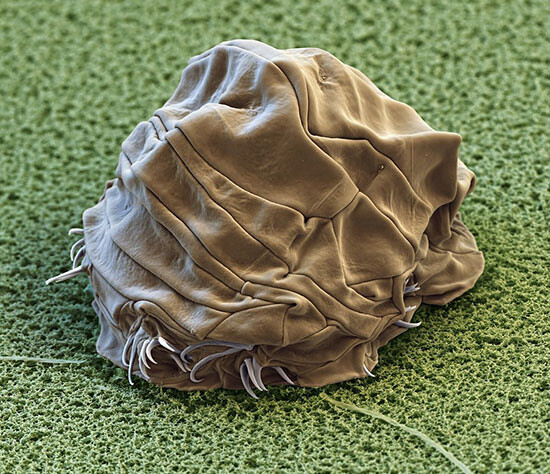

All of these stories are a lure to proposing the Chthulucene as a needed third story, a third netbag for collecting up what is crucial for ongoing, for staying with the trouble.44 The chthonic ones are not confined to a vanished past. They are a buzzing, stinging, sucking swarm now, and human beings are not in a separate compost pile. We are humus, not Homo, not anthropos; we are compost, not posthuman. As a suffix, the word kainos, “-cene,” signals new, recently made, fresh epochs of the thick present. To renew the biodiverse powers of terra is the sympoietic work and play of the Chthulucene. Specifically, unlike either the Anthropocene or the Capitalocene, the Chthulucene is made up of ongoing multispecies stories and practices of becoming-with in times that remain at stake, in precarious times, in which the world is not finished and the sky has not fallen — yet. We are at stake to each other. Unlike the dominant dramas of Anthropocene and Capitalocene discourse, human beings are not the only important actors in the Chthulucene, with all other beings able simply to react. The order is reknitted: human beings are with and of the Earth, and the biotic and abiotic powers of this Earth are the main story.

However, the doings of situated, actual human beings matter. It matters with which ways of living and dying we cast our lot rather than others. It matters not just to human beings, but also to those many critters across taxa which and whom we have subjected to exterminations, extinctions, genocides, and prospects of futurelessness. Like it or not, we are in the string figure game of caring for and with precarious worldings made terribly more precarious by fossil-burning man making new fossils as rapidly as possible in orgies of the Anthropocene and Capitalocene. Diverse human and nonhuman players are necessary in every fiber of the tissues of the urgently needed Chthulucene story. The chief actors are not restricted to the too-big players in the too-big stories of Capitalism and the Anthropos, both of which invite odd apocalyptic panics and even odder disengaged denunciations rather than attentive practices of thought, love, rage, and care.

Both the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene lend themselves too readily to cynicism, defeatism, and self-certain and self-fulfilling predictions, like the “game over, too late” discourse I hear all around me these days, in both expert and popular discourses, in which both technotheocratic geoengineering fixes and wallowing in despair seem to coinfect any possible common imagination. Encountering the sheer not-us, more-than-human worlding of the coral reefs, with their requirements for ongoing living and dying of their myriad critters, is also to encounter the knowledge that at least 250 million human beings today depend directly on the ongoing integrity of these holobiomes for their own ongoing living and dying well. Diverse corals and diverse people and peoples are at stake to and with each other. Flourishing will be cultivated as a multispecies response-ability without the arrogance of the sky gods and their minions, or else biodiverse terra will flip out into something very slimy, like any overstressed complex adaptive system at the end of its abilities to absorb insult after insult.

Corals helped bring the Earthbound into consciousness of the Anthropocene in the first place. From the start, uses of the term Anthropocene emphasized human-induced warming and acidification of the oceans from fossil-fuel-generated CO2 emissions. Warming and acidification are known stressors that sicken and bleach coral reefs, killing the photosynthesizing zooanthellae and so ultimately their cnidarian symbionts and all of the other critters belonging to myriad taxa whose worlding depends on intact reef systems. Corals of the seas and lichens of the land also bring us into consciousness of the Capitalocene, in which deep-sea mining and drilling in oceans and fracking and pipeline construction across delicate lichen-covered northern landscapes are fundamental to accelerating nationalist, transnationalist, and corporate unworlding.

But coral and lichen symbionts also bring us richly into the storied tissues of the thickly present Chthulucene, where it remains possible — just barely — to play a much better SF game, in nonarrogant collaboration with all those in the muddle. We are all lichens; so we can be scraped off the rocks by the Furies, who still erupt to avenge crimes against the Earth. Alternatively, we can join in the metabolic transformations between and among rocks and critters for living and dying well. “ ‘Do you realize,’ the phytolinguist will say to the aesthetic critic, ‘that [once upon a time] they couldn’t even read Eggplant?’ And they will smile at our ignorance, as they pick up their rucksacks and hike on up to read the newly deciphered lyrics of the lichen on the north face of Pike’s Peak.’ ”45 Attending to these ongoing matters returns me to the question that began this text. What happens when human exceptionalism and the utilitarian individualism of classical political economics become unthinkable in the best sciences across the disciplines and interdisciplines? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with. Why is it that the epochal name of the Anthropos imposed itself at just the time when understandings and knowledge practices about and within symbiogenesis and sympoietics are wildly and wonderfully available and generative in all the humusities, including noncolonizing arts, sciences, and politics? What if the doleful doings of the Anthropocene and the unworldings of the Capitalocene are the last gasps of the sky gods, not guarantors of the finished future, game over? It matters which thoughts think thoughts.

We must think!

The unfinished Chthulucene must collect up the trash of the Anthropocene, the exterminism of the Capitalocene, and chipping and shredding and layering like a mad gardener, make a much hotter compost pile for still possible pasts, presents, and futures.

Scott Gilbert, “We Are All Lichens Now” →. See also Gilbert, Jan Sapp, and Alfred I. Tauber, “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals,” Quarterly Review of Biology, vol. 87, no. 4 (December 2012): 325–41. Gilbert has erased the “now” from his rallying cry; we have always been symbionts—genetically, developmentally, anatomically, physiologically, neurologically, ecologically.

These sentences are on the rear cover of Isabelle Stengers and Vincinae Despret, Women Who Make a Fuss:The Unfaithful Daughters of Virginia Woolf, trans. April Knutson (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014). From Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas, “think we must” is the urgency relayed to feminist collective thinking-with in Women Who Make a Fuss through María Puig de la Bellacasa, Penser nous devons: Politiques féminists et construction des saviors (Paris: Harmattan, 2013).

Gustavo Hormiga, “A Revision and Cladistic Analysis of the Spider Family Pimoidae (Aranae: Araneae),” Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 549 (1994): 1–104. See “Pimoa cthulhu,” Wikipedia; “Hormiga Laboratory” →.

The brand of holist ecological philosophy that emphasizes that ‘everything is connected to everything,’ will not help us here. Rather, everything is connected to something, which is connected to something else. While we may all ultimately be connected to one another, the specificity and proximity of connections matters—who we are bound up with and in what ways. Life and death happen inside these relationships. And so, we need to understand how particular human communities, as well as those of other living beings, are entangled, and how these entanglements are implicated in the production of both extinctions and their accompanying patterns of amplified death.” Thom Van Dooren, Flight Ways: Life at the Edge of Extinction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 60.

Two indispensable books by my colleague-sibling from thirty-plus years in the History of Consciousness Department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, guide my writing: James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); and Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

Chthonic” derives from ancient Greek khthonios, “of the earth,” and from khthōn, “earth.” Greek mythology depicts the chthonic as the underworld, beneath the Earth; but the chthonic ones are much older (and younger) than those Greeks. Sumeria is a riverine civilizational scene of emergence of great chthonic tales, including possibly the great circular snake eating its own tail, the polysemous Ouroboros (figure of the continuity of life, an Egyptian figure as early as 1600 BCE; Sumerian SF worlding dates to 3500 BCE or before). The chthonic will accrue many resonances throughout my text. See Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1976). In lectures, conversations, and e-mails, the scholar of ancient Middle Eastern worlds at UC Santa Cruz, Gildas Hamel, gave me “the abyssal and elemental forces before they were astralized by chief gods and their tame committees” (personal communication, June 12, 2014). Cthulu (note spelling), luxuriating in the science fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, plays no role for me, although it/he did play a role for Gustavo Hormiga, the scientist who named my spider demon familiar. For the monstrous male elder god (Cthulu), see Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulu.

Eva Hayward proposes the term “tentacularity”; her trans-thinking and -doing in spidery and coralline worlds entwine with my writing in SF patterns. See Hayward, “FingeryEyes: Impressions of Cup Corals,” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 24, no. 4 (2010): 577–99; Hayward, “SpiderCitySex,” Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, vol. 20, no. 3 (2010): 225–51; and Hayward, “Sensational Jellyfish: Aquarium Affects and the Matter of Immersion,” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol. 23, no. 1 (2012): 161–96. See Eleanor Morgan, “Sticky Tales: Spiders, Silk, and Human Attachments,” Dandelion, vol. 2, no. 2 (2011) →. UK experimental artist Eleanor Morgan’s spider silk art spins many threads resonating with this chapter, tuned to the interactions of animals (especially arachnids and sponges) and humans. See Morgan’s website →.

Tim Ingold, Lines, a Brief History (New York: Routledge, 2007), 116–19.

The pile was made irresistible by María Puig de la Bellacasa, “Encountering Bioinfrastructure: Ecological Movements and the Sciences of Soil,” Social Epistemology vol. 28, no. 1 (2014): 26–40.

Isabelle Stengers, Au temps des catastrophes: Résister à la barbarie qui vient (Paris: Découverte), 2009. Gaia intrudes in this text from p. 48 on. Stengers discusses the “intrusion of Gaïa” in numerous interviews, essays, and lectures. Discomfort with the ever more inescapable label of the Anthropocene, in and out of sciences, politics, and culture, pervades Stengers’s thinking, as well as that of many other engaged writers, including Latour, even as we struggle for another word. See Stengers in conversation with Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, “Matters of Cosmopolitics: On the Provocations of Gaïa,” in Architecture in the Anthropocene: Encounters among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy, ed. Etienne Turpin (London: Open Humanities, 2013), 171–82.

Scientists estimate that this extinction “event,” the first to occur during the time of our species, could, as previous great extinction events have, but much more rapidly, eliminate 50 to 95 percent of existing biodiversity. Sober estimates anticipate half of existing species of birds could disappear by 2100. By any measure, that is a lot of double death. For a popular exposition, see Voices for Biodiversity, “The Sixth Great Extinction” →. For a report by an award-winning science writer, see Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History (New York: Henry Holt, 2014). Reports from the Convention on Biological Diversity are more cautious about predictions and discuss the practical and theoretical difficulties of obtaining reliable knowledge, but they are not less sobering. For a disturbing report from summer 2015, see Geraldo Ceballos, Paul Ehrlich, Anthony Barnosky, Andres Garcia, Robert Pringle, and Todd Palmer, “Accelerated Modern Human-Induced Species Losses: Entering the Sixth Mass Extinction,” Science Advances vol. 1, no. 5 (June 19, 2015).

Lovelock, “Gaia as Seen through the Atmosphere,” Atmospheric Environment, vol. 6, no. 8 (1967): 579–80; Lovelock and Margulis, “Atmospheric Homeostasis by and for the Biosphere: The Gaia Hypothesis,” Tellus, Series A (Stockholm: International Meteorological Institute) vol. 26, nos. 1–2 (February 1, 1974): 2–10 →. For a video of a lecture to employees at the National Aeronautic and Space Agency in 1984, go to →. Autopoiesis was crucial to Margulis’s transformative theory of symbiogenesis, but I think if she were alive to take up the question, Margulis would often prefer the terminology and figural-conceptual powers of sympoiesis. I suggest that Gaia is a system mistaken for autopoietic that is really sympoietic. Gaia’s story needs an intrusive makeover to knot with a host of other promising sympoietic tentacular ones for making rich compost, for going on. Gaia or Ge is much older and wilder than Hesiod (Greek poet around the time of Homer, circa 750 to 650 BCE), but Hesiod cleaned her/it up in the Theogony in his story-setting way: after Chaos, “wide-bosomed” Gaia (Earth) arose to be the everlasting seat of the immortals who possess Olympus above (Theogony, 116–18, trans. Glenn W. Most, Loeb Classical Library), and the depths of Tartarus below (Theogony, 119). The chthonic ones reply, Nonsense! Gaia is one of theirs, an ongoing tentacular threat to the astralized ones of the Olympiad, not their ground and foundation, with their ensuing generations of gods all arrayed in proper genealogies. Hesiod’s is the old prick tale, already setting up canons in the eighth century BCE.

Although I cannot help but think more rational environmental and socialnatural policies of all sorts would help!

Isabelle Stengers, from English compilation on Gaia sent by e-mail January 14, 2014.

I use “thing” in two senses that rub against each other: (1) the collection of entities brought together in the Parliament of Things that Bruno Latour called our attention to, and (2) something hard to classify, unsortable, and probably with a bad smell. Latour, We Have Never Been Modern (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” Global Change Newsletter, International Geosphere-Biosphere Program Newsletter, no. 41 (May 2000): 17–18 →; Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415 (2002): 23; Jan Zalasiewicz et al., “Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?” GSA (Geophysical Society of America) Today vol. 18, no. 2 (2008): 4–8. Much earlier dates for the emergence of the Anthropocene are sometimes proposed, but most scientists and environmentalists tend to emphasize global anthropogenic effects from the late eighteenth century on. A more profound human exceptionalism (the deepest divide of nature and culture) accompanies proposals of the earliest dates, coextensive with Homo sapiens on the planet hunting big now-extinct prey and then inventing agriculture and domestication of animals. A compelling case for dating the Anthropocene from the multiple “great accelerations,” in Earth system indicators and in social change indicators, from about 1950 on, first marked by atmospheric nuclear bomb explosions, is made by Will Steffen, Wendy Broadgate, Lisa Deutsch, Owen Gaffney, and Cornelia Ludwig, “The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration,” The Anthropocene Review, January 16, 2015. Zalasiewicz et al. argue that adoption of the term “Anthropocene” as a geological epoch by the relevant national and international scientific bodies will turn on stratigraphic signatures. Perhaps, but the resonances of the Anthropocene are much more disseminated than that. One of my favorite art investigations of the stigmata of the Anthropocene is Ryan Dewey’s “Virtual Places: Core Logging the Anthropocene in Real-Time,” in which he composes “core samples of the ad hoc geology of retail shelves.”

For a powerful ethnographic encounter in the 1990s with climate-change modeling, see Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, “Natural Universals and the Global Scale,” ch. 3 in Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 88–112, especially “Global Climate as a Model,” 101–6. Tsing asks, “What makes global knowledge possible?” She replies, “Erasing collaborations.” But Tsing does not stop with this historically situated critique. Instead she, like Latour and Stengers, takes us to the really important question: “Might it be possible to attend to nature’s collaborative origins without losing the advantages of its global reach?” (95). “How might scholars take on the challenge of freeing critical imaginations from the specter of neoliberal conquest—singular, universal, global? Attention to the frictions of contingent articulation can help us describe the effectiveness, and the fragility, of emergent capitalist—and globalist—forms. In this shifting heterogeneity there are new sources of hope, and, of course, new nightmares” (77). At her first climate-modeling conference in 1995, Tsing had an epiphany: “The global scale takes precedence—because it is the scale of the model” (103, italics in original). But this and related properties have a particular effect: they bring negotiators to an international, heterogeneous table, maybe not heterogeneous enough, but far from full of identical units and players. “The embedding of smaller scales into the global; the enlargement of models to include everything; the policy-driven construction of the models: Together these features make it possible for the models to bring diplomats to the negotiating table” (105). That is not to be despised.

The Anthropocene Working Group, which was established in 2008 to report to the International Union of Geological Sciences and the International Commission on Stratigraphy on whether to name a new epoch in the geological timeline, aimed to issue its final report in 2016. See Newsletter of the Anthropocene Working Group, volume 4 (June 2013): 1–17 →; and volume 5 (September 2014): 1–19 →.

For a photogallery of fiery images of the Man burning at the end of the festival, see “Burning Man Festival 2012: A Celebration of Art, Music, and Fire,” New York Daily News, September 3, 2012 →. Attended by tens of thousands of human people (and an unknown number of dogs), Burning Man is an annual week-long festival of art and (commercial) anarchism held in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada since 1990 and on San Francisco’s Baker Beach from 1986 to 1990. The event’s origins tie to San Francisco artists’ celebrations of the summer solstice. “The event is described as an experiment in community, art, radical self-expression, and radical self-reliance” (“Burning Man,” Wikipedia). The globalizing extravaganzas of the Anthropocene are not the drug- and art-laced worlding of Burning Man, but the iconography of the immense fiery “Man” ignited during the festival is irresistible. The first burning effigies on the beach in San Francisco were of a nine-foot-tall wooden Man and a smaller wooden dog. By 1988 the Man was forty feet tall and dogless. Relocated to a dry lakebed in Nevada, the Man topped out in 2011 at 104 feet. This is America; supersized is the name of the game, a fitting habitat for the Anthropos.

See Klare, “The Third Carbon Age,” Huffington Post, August 8, 2013 →, in which he writes, “According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), an inter-governmental research organization based in Paris, cumulative worldwide investment in new fossil-fuel extraction and processing will total an estimated $22.87 trillion between 2012 and 2035, while investment in renewables, hydropower, and nuclear energy will amount to only $7.32 trillion.” Nuclear, after Fukushima! Not to mention that none of these calculations prioritize a much lighter, smaller, more modest human presence on Earth, with all its critters. Even in its “sustainability” discourses, the Capitalocene cannot tolerate a multispecies world of the Earthbound. For the switch in Big Energy’s growth strategies to nations with the weakest environmental controls, see Klare, “What’s Big Energy Smoking?” Common Dreams, May 27, 2014 →. See also Klare, The Race for What’s Left: The Global Scramble for the World’s Last Resources (New York: Picador, 2012).

Heavy tar sand pollution must break the hearts and shatter the gills of every Terran, Gaian, and Earthbound critter. The toxic lakes of wastewater from tar sand oil extraction in northern Alberta, Canada, shape a kind of new Great Lakes region, with more giant “ponds” added daily. Current area covered by these lakes is about 50 percent greater than the area covered by the world city of Vancouver. Tar sands operations return almost none of the vast quantities of water they use to natural cycles. Earthbound peoples trying to establish growing things at the edges of these alarmingly colored waters filled with extraction tailings say that successional processes for reestablishing sympoietic biodiverse ecosystems, if they prove possible at all, will be an affair of decades and centuries. See Pembina Institute, “Alberta’s Oil Sands” →; and Bob Weber, “Rebuilding Land Destroyed by Oil Sands May Not Restore It,” Globe and Mail, March 11, 2012 →. Only Venezuela and Saudi Arabia have more oil reserves than Alberta. All that said, the Earthbound, the Terrans, do not cede either the present or the future; the sky is lowering, but has not yet fallen, yet. Pembina Institute, “Oil Sands Solutions” →. First Nation, Métis, and Aboriginal peoples are crucial players in every aspect of this unfinished story.

Photograph from NASA Earth Observatory, 2015 (public domain). If flame is the icon for the Anthropocene, I use the missing ice and the unblocked Northwest Passage to figure the Capitalocene. The Soufan Group provides strategic security intelligence services to governments and multinational organizations. Its report “TSG IntelBrief: Geostrategic Competition in the Arctic” includes the following quotes: “The Guardian estimates that the Arctic contains 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 15 percent of its oil.” “In late February, Russia announced it would form a strategic military command to protect its Arctic interests.” “Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark, and the US all make some claim to international waters and the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean.” “(A Northwest Passage) route could provide the Russians with a great deal of leverage on the international stage over China or any other nation dependent on sea commerce between Asia and Europe.”

Naomi Klein, “How Science Is Telling Us All to Revolt,” New Statesman, October 29, 2013 →; Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Macmillan/Picador, 2008).

“Capitalocene”is one of those words like“sympoiesis”; if you think you invented it, justlook around and notice how many other people are inventing the term at the same time. That certainly happened to me, and after I got over a small fit of individualist pique at being asked whom I got the term “Capitalocene” from—hadn’t I coined the word? (“Coin”!) And why do other scholars almost always ask women which male writers their ideas are indebted to?—I recognized that not only was I part of a cat’s cradle game of invention, as always, but that Jason Moore had already written compelling arguments to think with, and my interlocutor both knew Moore’s work and was relaying it to me. Moore himself first heard the term “Capitalocene” in 2009 in a seminar in Lund, Sweden, when then graduate student Andreas Malm proposed it. In an urgent historical conjuncture, words-to-think-with pop out all at once from many bubbling cauldrons because we all feel the need for better netbags to collect up the stuff crying out for attention. Despite its problems, the term “Anthropocene” was and is embraced because it collects up many matters of fact, concern, and care; and I hope “Capitalocene” will roll off myriad tongues soon.

To get over Eurocentrism while thinking about the history of pathways and centers of globalization over the last few centuries, see Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Giráldez, China and the Birth of Globalisation in the 16th Century (Farnum, UK: Ashgate Variorium, 2012). For analysis attentive to the differencesand frictions among colonialisms, imperialisms, globalizing trade formations, and capitalism, see Engseng Ho, “Empire through Diasporic Eyes: A View from the Other Boat,” Society for Comparative Study of Society and History (April 2004): 210–46; and Ho, The Graves of Tarem: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

In “Anthropocene or Capitalocene, Part III,” May 19, 2013 →, Jason Moore puts it this way: “This means that capital and power—and countless other strategic relations—do not act upon nature but develop through the web of life. ‘Nature’ is here offered as the relation of the whole. Humans live as a specifically endowed (but not special) environment-making species within Nature. Second, capitalism in 1800 was no Athena, bursting forth, fully grown and armed, from the head of a carboniferous Zeus. Civilizations do not form through Big Bang events. They emerge through cascading transformations and bifurcations of human activity in the web of life … the long seventeenth century forest clearances of the Vistula Basin and Brazil’s Atlantic Rainforest occurred on a scale, and at a speed, between five and ten times greater than anything seen in medieval Europe.”

Crist, “On the Poverty of Our Nomenclature,” Environmental Humanities 3 (2013): 129–47; 144. Crist does superb critique of the traps of Anthropocene discourse, as well as gives us propositions for more imaginative worlding and ways to stay with the trouble. For entangled, dissenting papers that both refuse and take up the name Anthropocene, see videos from the conference “Anthropocene Feminism,” University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, April 10–12, 2014 →. For rich interdisciplinary research, organized by Anna Tsing and Nils Ole Bubandt, that brings together anthropologists, biologists, and artists under the sign of the Anthropocene, see AURA: Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene →.

I owe the insistence on “big-enough stories” to Clifford, Returns: “I think of these as ‘big enough’ histories, able to account for a lot, but not for everything—and without guarantees of political virtue” (201). Rejecting one big synthetic account or theory, Clifford works to craft a realism that “works with open-ended (because their linear historical time is ontologically unfinished) ‘big-enough stories,’ sites of contact, struggle, and dialogue” (85–86).

Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers, La sorcellerie capitaliste: Pratiques de désenvoûtement (Paris: Découverte, 2005). Latour and Stengers are deeply allied in their fierce rejection of discourses of denunciation. They have both patiently taught me to understand and relearn in this matter. I love a good denunciation! It is a hard habit to unlearn.

It is possible to read Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment as an allied critique of Progress and Modernization, even though theirresolute secularism gets in their own way. It is very hard for a secularist to really listen to the squid, bacteria, and angry old women of Terra/Gaia. The most likely Western Marxist allies, besides Marx, for nurturing the Chthulucene in the belly of the Capitalocene are Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, and Stuart Hall. Hall’s immensely generative essays extend from the 1960s through the 1990s. See, for example, Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, eds. David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen (London: Routledge, 1996).

See Dave Gilson, “Octopi Wall Street!” Mother Jones, October 6, 2011 →, for the fascinating history of cephalopods figuring the depredations of Big Capital in the United States (for example, the early twentieth-century John D. Rockefeller/Standard Oil octopus strangling workers, farmers, and citizens in general with its many huge tentacles). Resignification of octopuses and squids as chthonic allies is excellent news. May they squirt inky night into the visualizing apparatuses of the technoid sky gods.

Hesiod’s Theogony in achingly beautiful language tells of Gaia/Earth arising out of Chaos to be the seat of the Olympian immortals above and of Tartarus in the depths below. She/it is very old and polymorphic and exceeds Greek tellings, but just how remains controversial and speculative. At the very least, Gaia is not restricted to the job of holding up the Olympians! The important and unorthodox scholar-archaeologist Marija Gimbutis claims that Gaia as Mother Earth is a later form of a pre–Indo-European, Neolithic Great Mother. In 2004, filmmaker Donna Reed and neopagan author and activist Starhawk released a collaborative documentary film about the life and work of Gimbutas, Signs out of Time. See Belili Productions, “About Signs out of Time” →; Gimbutas, The Living Goddesses,ed. Miriam Robbins Dexter (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

To understand what is at stake in “non-Euclidean” storytelling, go to Le Guin, Always Coming Home (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985);and Le Guin, “A Non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold Placeto Be,” in Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places (New York: Grove, 1989), 80–100.

“The Thousand Names of Gaia: From the Anthropocene to the Age of the Earth,” International Colloquium, Rio de Janeiro, September 15–19, 2014.

The bee was one of Potnia Theron’s emblems, and she is also called Potnia Melissa, Mistress of the Bees. Modern Wiccans remember these chthonic beings in ritual and poetry. If fire figured the Anthropocene, and ice marked the Capitalocene, it pleases me to use red clay pottery for the Chthulucene, a time of fire, water, and Earth, tuned to the touch of its critters, including its people. With her PhD writing on the riverine goddess Ratu Kidul and her dances now performed on Bali, Raissa DeSmet (Trumbull) introduced me to the web of far-traveling chthonic tentacular ones emerging from the Hindu serpentine Nagas and moving through the waters of Southeast Asia. DeSmet, “A Liquid World: Figuring Coloniality in the Indies,” PhD diss., History of Consciousness Department, University of California at Santa Cruz, 2013.

Links between Potnia Theron and the Gorgon/Medusa continued in temple architecture and building adornment well after 600 BCE, giving evidence of the tenacious hold of the chthonic powers in practice, imagination, and ritual, for example, from the fifth through the third centuries BCE on the Italian peninsula. The dread-full Gorgon figure faces outward, defending against exterior dangers, and the no less awe-full Potnia Theron faces inward, nurturing the webs of living. See Kimberly Sue Busby, “The Temple Terracottas of Etruscan Orvieto: A Vision of the Underworld in the Art and Cult of Ancient Volsinii,” PhD diss., University of Illinois, 2007. The Christian Mary, Virgin Mother of God, who herself erupted in the Near East and Mediterranean worlds, took on attributes of these and other chthonic powers in her travels around the world. Unfortunately, Mary’s iconography shows her ringed by stars and crushing the head of the snake (for example, in the Miraculous Medal dating from an early nineteenth-century apparition of the Virgin), more than allying herself with Earth powers. The “lady surrounded by stars” is a Christian scriptural apocalyptic figure for the end of time. That is a bad idea. Throughout my childhood, I wore a gold chain with the Miraculous Medal. Finally and luckily, it was her residual chthonic infections that took hold in me, turning me from both the secular and also the sacred, and toward humus and compost.

The Hebrew word Deborah means “bee,” and she was the only female judge mentioned in the Bible. She was a warrior and counselor in premonarchic Israel. The Song of Deborah may date to the twelfth centuryBCE. Deborah was a military heroand ally of Jael, one of the 4Js in Joanna Russ’s formative feminist science fiction novel The Female Man.

“Erinyes 1,” Theoi Greek Mythology →

Martha Kenney pointed out to me that the story of the Ood, in the long-running British science fiction TV series Doctor Who, shows how the squid-faced ones became deadly to humanity only after they were mutilated, cut off from their symchthonic hive mind, and enslaved. The humanoid empathic Ood have sinuous tentacles over the lower portion of their multifolded alien faces; and in their proper bodies they carry their hindbrains in their hands, communicating with each other telepathically through these vulnerable, living, exterior organs (organons). Humans (definitely not the Earthbound) cut off the hindbrains and replaced them with a technological communication-translator sphere, so that the isolated Ood could only communicate through their enslavers, who forced them into hostilities. I resist thinking the Ood techno-communicators are a future release of the iPhone, but it is tempting when I watch the faces of twenty-first-century humans on the streets, or even at the dinner table, apparently connected only to their devices. I am saved from this ungenerous fantasy by the SF fact that in the episode “Planet of the Ood,” the tentacular ones were freed by the actions of Ood Sigma and restored to their nonsingular selves. Doctor Who is a much better story cycle for going-on-with than Star Trek.

“Medousa and Gorgones,” Theoi Greek Mythology →

Suzy McKee Charnas’s Holdfast Chronicles, beginning in 1974 with Walk to the End of the World, is greatSFfor thinking about feminists and their horses. The sex isexciting if very incorrect, and the politics are bracing.

Eva Hayward first drew my attention to the emergence of Pegasus from Medusa’s body and of coral from drops of her blood. In her “The Crochet Coral Reef Project Heightens Our Sense of Responsibility to the Oceans,” Independent Weekly, August 1, 2012,” she writes: “If coral teaches us about the reciprocal nature of life, then how do we stay obligated to environments—many of which we made unlivable—that now sicken us? … Perhaps Earth will follow Venus, becoming uninhabitable due to rampaging greenhouse effect. Or, maybe, we will rebuild reefs or construct alternate homes for the oceans’ refugees. Whatever the conditions of our future, we remain obligate partners with oceans.” See Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, Crochet Coral Reef: A Project by the Institute for Figuring (Los Angeles: IFF, 2015).

I am inspired by the 2014–15 Monterey Bay Aquarium exhibition Tentacles: The Astounding Lives of Octopuses, Squids, and Cuttlefish. See Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant, Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society, trans. Janet Lloyd (Brighton, UK: Harvester Press, 1978), with thanks to Chris Connery for this reference in which cuttlefish, octopuses, and squid play a large role. Polymorphy, the capacity to make a net or mesh of bonds, and cunning intelligence are the traits the Greek writers foregrounded. “Cuttlefish and octopuses are pure áporai and the impenetrable pathless night they secrete is the most perfect image of their metis” (38). Chapter 5, “The Orphic Metis and the Cuttle-Fish of Thetis,” is the most interesting for the Chthulucene’s own themes of ongoing looping, becoming-with, and polymorphism. “The suppleness of molluscs, which appear as a mass of tentacles (polúplokoi), makes their bodies an interlaced network, a living knot of mobile animated bonds” (159). For Detienne and Vernant’s Greeks, the polymorphic and supple cuttlefish are close to the primordial multisexual deities of the sea—ambiguous, mobile, and ever changing, sinuous and undulating, presiding over coming-to-be, pulsating with waves of intense color, cryptic, secreting clouds of darkness, adept at getting out of difficulties, and having tentacles where proper men would have beards.

See Donna Haraway and Martha Kenney, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” interview for Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters among Aesthetics, Politics, Environment, and Epistemology, ed. Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin (Open Humanities Press, Critical Climate Change series, 2015) →

Le Guin, “‘The Author of Acacia Seeds’ and Other Extracts from the Journal of the Association of Theolinguistics,” in Buffalo Gals and Other Animal Presences (New York: New American Library, 1988), 175.

Category

Subject

This text is an edited extract from chapter 2, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” in Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, 2016. Copyright, 2016, Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the copyright holder. www.dukeupress.edu