From 1772–75, Reinhold and Georg Forster, a father and son team of German naturalists, accompanied Captain James Cook on his second Pacific expedition. The voyage sought to map the unknown reaches of the South Pacific, and to discover the imagined Great Southern Continent. While anchored in the Melanesian archipelago (now New Caledonia), Third Lieutenant Richard Pickersgill encountered the social body of the ship’s map-making. The Forsters’s journal records the following scene in the course of their disembarking:

Mr. Pickersgill found it advisable to draw lines on the sand in order to secure the clothes of his people. The natives very readily came into his proposal, and never crossed the lines. One of them, however, seemed to be more surprised than all the rest at this contrivance, and with a great deal of humor drew a circle round about himself, on the ground, with a stick; and intimated, by many ludicrous gestures, that everybody present should keep at a distance from him.1

Like the stick pulled through sand to create a line, the frontier marks the point at which the soaring ideals of modernity touch ground. In this morphology of contact, the frontier concerns how the “outside” is produced, exploited, and policed. Today the frontier is marked by its troubling persistence; the pan-European “Frontex” recalls the brute politics of Europe’s imperial era; the cyber security industry hails news forms of lawlessness across the “digital frontier,” and technological advancement offers new extractive possibilities both at territorial extremes (offshore drilling) and underneath urbanized lands (fracking).

What follows is a set of five departures from the Forsters’s tale, each of which works toward a concept-image of the persistent presence of the frontier within the globalizing era. The move to recover the frontier as a critical tool turns again toward the clash between enlightenment ideals such as “justice” and “equality” and the obdurate violence of the world those ideas must inhabit. The lens of the frontier shifts the point of view to the margins, reframing these ideals as encounters with the violence of the world they create.

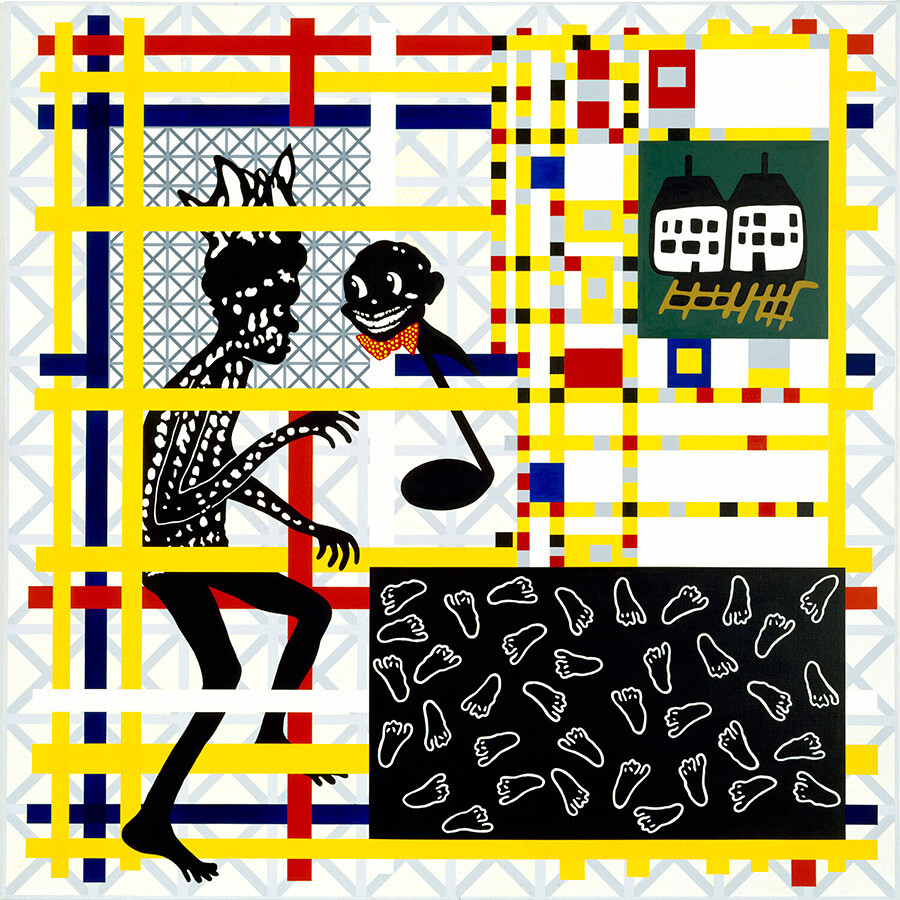

Gordon Bennett, Home Decor (Preston + De Stijl = Citizen) Dance the Boogieman Blues, 1997. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Private collection.

1. A Line in the Sand: The Frontier as a Ground of Reinscription

The hand that marks a line in the sand separating “yours” from “mine” is a hand that inscribes its name into territory. It is a hand that vests authority in the signature, and that upholds contractual relations in the written form.

My interest in the frontier began in Brisbane, Australia more than two years ago, during separate conversations with two senior artists dealing with aboriginality: the provocateur Richard Bell, and the painter Gordon Bennett, since deceased. While the two disagreed sharply on questions of identity politics, the story of their path toward becoming artists shared a common turn; both withdrew from regular employment on account of the unendurable racism within the Australian system.

Their embrace of the role of the artist rehearses the “problem” of aboriginal Australia as an instance of the frontier predicament of capital: How to turn a rebellious population into a value-producing labor force? The Marxian account of primitive accumulation as the horizon of capitalist modernity locates this problem firmly in the past, as the precondition for capitalist accumulation. Yet the resilience of the frontier points to its beyond; upsetting historical materialist conditioning and its notions of temporal progress.

From 1720 to 1832 the Enclosure Acts inaugurated a legal process of land dispossession in Britain, allowing landowners to turn farms and common spaces into pastures for sheep. This sent tens of thousands of suddenly unemployed farmworkers streaming into the cities in search of a way to make a living. The eighteenth-century rebirth of the Roman proletarii—or propertyless—shifted power toward the sovereign, inaugurating the modern relations of capital/labor.

However, the relations of capital/labor have always been underpinned by those of nature/culture. The work of autonomist feminist Sylvie Federici, for example, has left no doubt as to the disciplining of women that is required to secure the relations of capital, as well as the persecution of local, herbal knowledge and of pagan worlds. The work of primitive accumulation has always relied upon vast and intimately etched reinscriptions at the cosmopolitical level. Attention to the frontier itself makes this known.

A plate from the book The White King; or, The Life and Reign of Emperor Maximilian I, Part 2, Chapter 23, is captioned “How the Young White King learned the Black Arts.”

Take for example the mass de-registration of sacred sites in Western Australia, occurring conspicuously amid the tail end of a mineral resources boom. Between 2010 and 2015 the government regulator has actively de-registered over three thousand sites that had been marked for protection in relation to Aboriginal heritage. The scales have been tipped dramatically; what used to be a 90 percent acceptance rate of sites submitted for recognition has fallen to just 14 percent.

In a recent interview, anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli toyed with the idea of writing an article titled “The Australian Taliban”—equating the scale of the destruction wrought by the non-recognition of sacred sites with the dynamiting of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Afghan Taliban in 2001. The weapon in the Australian case, however, is not dynamite, but rather a shift in juridical language—a redrawing of the frontier—between a “site” and its “sacredness.” As Povinelli explains:

The Western Australian government … changed the definitional criteria of sacred sites, demanding every site conform more tightly to the practices and activities of religions of the book—that they be a holy site in the sense of a place where worshipers come and practice the tenets of their faith. Wherever two or more are gathered constantly and regularly, now there is a sacred site, and thus banished from legislative protection is a core Indigenous ontological analytics—that [the sacred] is the place that contains and concentrates the energies of the land and that constitutes the world regardless of whether or not humans are there from one moment to the next.2

Once we understand the frontier as a ground of perpetual reinscription, the narrative requirements for its re-mattering become clear. The frontier arises first and foremost as a ground of reinscription. Deregistration is an official story told for the operations of legally sanctioned dispossession. It is one that clears the way for extractive profiteering through a ricochet between the legal and the literal emptying out of the land. Povinelli adds:

These are not deserted lands. These are desecrated lands being made into deserts. They are expressions of geontopower—the management of life and nonlife, what must be made into the inert in order to continue to fuel capital.3

As such, the cut of the frontier goes beyond the creation of wage labor—as in the Marxian reading of the Enclosure Acts, for example—impacting infrastructures of kinship and land relations that are always already implicit in the economic workings of the political.

2. The Property of Clothes and the Clothing of Property

The frontier, at its base, checks dis/possession and the moral economy of propriety against the “proper” relations of gender and sexuality vis-à-vis the Racial and Colonial Other. This appears to be figured into the Forsters’s account in its focus on the property of clothes as part of a vast and gendered socio-cosmology that adjudicates and disciplines touch, intimacy, dwelling, and inheritance.

This is made beautifully and hilariously clear in Marco Ferreri’s 1971 spaghetti-western farce Don’t Touch the White Woman. In a stunning feat of location filming, the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn (Custer’s Last Stand) is restaged against the backdrop of the raw excavations of Paris’s Les Halles of the 1970s. It is set against a backdrop, that is, consisting of an enormous hole in the ground in inner-city Paris awaiting urban development.

At the time Les Halles was an ulcer in Paris’s urban skin. Abandoned, and by then long overdue for reconstruction, it became known as “Les Trous des Halles,” or the hole of Les Halles. Its 1970s renovation was the second for the site, marking three distinct epochs in the commercialization of French civil society and its relation to state or sovereign control.

In 1183, Philip II—the original monarch to style himself as King of France—enlarged and formalized Les Halles, the traditional market place of Paris, by building a shelter to host its merchants and protect their wares. In the 1850s, as part of a wave of reforms designed in part to facilitate control over rebellious urban populations, the market was transformed into a long grid of iron and glass pavilions—a secular cathedral dedicated to the products of France’s industry and agriculture. The next wave or reform—the gentrifying redevelopment of the 1970s—continues more or less to the present, with rounds of “starchitect” competitions held to more impressively service the Parisian citizen now recast as lifestyle consumer.

This dynamic is captured perfectly in the trailer for Don’t Touch the White Woman. In it, a compelling physiognomy of the sheer rock faces of Les Halles is layered with the frontier melee of the Wild West. Dust and bullets fly as hooves rumble and cries ring out from the Sioux and Cavalry forces. Spliced into the end of these scenes is Catherine Deneuve—a.k.a. the white woman—alone in a boudoir gasping in erotic paroxysms.

The effect of this splicing is at once hilarious and profound. Deneuve’s female libidinal transmissions—separate from and yet underpinning the battlefield—sound the site’s threefold history, marking a defensive genealogical column among them. These forces of sex and desire, organized as geneaology, serve to stabilize the market’s historical architecture of property, even as its physical architecture is shattered and re-formed.

For researcher and activist Angela Mitropoulos, the genealogical takes on a specific force amid crises in the relations of capital. These appear as destabilizations in the proper socioeconomic order and can mark the transitions between different phases of capital, such as the three waves of commercial history inscribed in Les Halles and depicted as the crisis of gentrification in Ferreri’s image of frontier battle. According to Mitropoulos: “Genealogy inscribes and reinscribes the lines of legitimate production and reproduction in the midst of their deepest contestation and uncertainty.”4

This genealogical frame raises a queer lens to the critique of capital. It explains, among other things, the increasing acceptance of same-sex marriage by reading it against the evaporation of the cross-border potential of marriage, as—across much of the OECD world—matrimonial rights to citizenship are rapidly replaced by means-testing. Hence, as the global relations of labor take on a mass-migratory dimension, and the proper social order is recalibrated to privilege a new propriety of the same-sex couple against the arch impropriety of the rights-claiming migrant.

Thor H. Jensen, The Hill Farm Estate, Logan Road: Sale on the Ground Saturday 16th May 1914. Copyright: State Library of Queensland.

3. The Frontier Is Territory Turned Away From Itself

The maritime era saw the frontier expand with a twofold movement. While the forces of industrializing modernity were propelled toward the recognizable resource value of new territories, the colonial disposition was, by and large, turned against the eco-social worlds that encompassed them. As such, the settler society of the frontier is marked by a fortressed and defensive architecture.

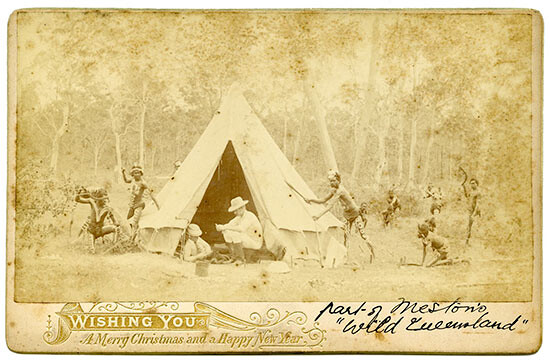

The settler mentality—made tangible in the form of the fortressed frontier—is currently exemplified in the Israeli separation wall, though it also proliferates on another scale through the picket and wire fencing of Australian and North American suburbia. The settler psyche—simultaneously fearful and in denial of its surroundings—is distilled in a staged photograph from Archibald Meston’s Wild Australia Show (1982–1993). Here a group of armed locals—who were in fact plucked from indigenous nations across the north and east coast—loom menacingly over the tent of two colonists who are oblivious to their apparently imminent demise.5

Thinking again of the performance recorded by the Forsters: What is it to arrive at a place, inscribe a portion of territory to oneself, and “with many ludicrous gestures” seek to banish what came before? The settler condition is to dwell in a place where one refuses to be—refusing one’s context by imagining a malicious environment and laboring to impose a fantasy of European origin. This profound ambivalence produces a cognitive dissonance within the settler society, managed in part through temporal displacement.

The history of this concept-structure within European epistemologies has been variously diagnosed. Johannes Fabian, for example, discusses an allochronic discourse by which the anthropologist’s subjects are posited in an ethnographic past.6 Elizabeth Povinelli points to a “governance of the prior,” extending her analysis by way of current Australian governance to consider the juridical forms of temporal disavowal that are particular to the post-Fordist (late-liberal) period.7

As anarchist geographer and communard Élisée Reclus noted in 1872, “geography is nothing but history in space.”8 The frontier thus becomes a territorial composite of modern eschatology: now the horizon towards which modernity confidently sails, seeking wealth and glory; now the encroaching, racinated darkness before which it recoils, imagining the ahistoric, the primitive, the unfathomable, and the monstrous.

4. The Frontier Anticipates an Axiomatic Order

Once the proprietorial line in the sand is enclosed in a circle, the imperative is to expand. The modus for doing so is the axiomatic, a reproduction of the same.

The frontier anticipates an order governed through calculable—i.e., endlessly exchangeable and hence indifferent—relations. This ordinal formation that grasps geographic expanse through metrics of projection has also been variously theorized, for example by media theorist McKenzie Wark as the “vectoral,” by anthropologist Rosalind C. Morris as an “Actuarial Age,” and which historian of science Lorraine Daston describes, referring to Cold War rationality, as an era in which “reason almost lost its mind.”9

An inscription upon a tombstone outside the town church of Prebberede-Belit, north of Berlin, bears witness to this axiomatic drive. It is the grave of Johann Heinrich von Thünen (1783–1850), widely considered the founder of economic geography and proponent of the mathematical modeling of land use. Here, upon a stone scroll, a small algorithm is engraved: √ap. It is a formula for the “frontier wage”—von Thünen’s solution to history in general—wherein “a” is the essential subsistence needs of the worker and “p” the product of his labor.

The tombstone of Johann Heinrich von Thünen (1783–1850), considered to be one of the founders of economic geography and a proponent of the mathematical modeling of land use, displays his formula for formula “frontier wage” engraved on its surface.

By von Thünen’s reckoning, this formula offered an approximation of the natural wage, the equilibrium point in the distribution of wealth at which both “workers and capitalists have a mutual interest in increasing production.”10 Its calculation was derived from the “Isolated State,” a completely flat territory with even soil type and a city located perfectly at the center.

For von Thünen, the natural wage could not be calculated within Europe on account of inherited inequality in land ownership. The frontier, however, could be envisioned as a limitless “laboratory” for the “world spirit” of capital. Von Thünen:

On the frontier of the cultivated plane of the Isolated State, where free land is to be had in unlimited quantities, neither the arbitrariness of the capitalists nor the competition of the workers, nor the magnitude of the necessary means of subsistence determines the amount of wages, but the product of labor is itself the yardstick for wages.11

In short, the frontier is modeled as an unpopulated Eden. The attendant denial of the worlds prior to the arrival of the frontier goes hand in glove with the denial of the brute violence by which these lands were evacuated and made ready to host the exchange relations of capital. As with Australia’s deregistration of sacred aboriginal sites, this dispossession is not just that of real estate and of resources; it is the dispossession of difference itself. The imperative of erasure is standardization, first of “property and rights” and more recently of “risk-exposure and insurance.”

5. The Imperial and the Global Frontier, and the “New” Arts of Possession

The frontier advanced across the flattened Earth of the Mercator projection as a line that marked knowing as possessing. It was only a few years before the Forsters’s diary, in 1770, that Captain Cook had laid claim to the east coast of Australia and the islands of Aotearoa/New Zealand from the northern point of Possession Island, a small landmass in the Torres Strait north of Queensland and south of Papua New Guinea.

This claim was itself inscribed in a poetics of possession sealed in the ritual of violence. In a three-part performance—on the cusp of the sunset—Cook raised the English Colors, read aloud a declaration in the name of King George the Third, and then “fired three Volleys of small Arms which were Answerd [sic] by the like number from the Ship.”12

There is a question arising from the urban swamps of the global age: What happens to the frontier once its cartographic line collapses—as the singular force of its horizon is overwritten by satellite grids and by the air, sea, and data routes of global commerce? How, where, and for whom does the frontier rematerialize as a territorial condition? And what form does it take in the era that follows formal—politico-juridical—decolonization; a period that has witnessed a proliferation of nation-states swiftly followed by the deterritorialization (denationalization) of their currencies and markets?

This transition has produced what can be differentiated as the “imperial” and the “global” frontier. Geography—understood via Reclus as territory inscribed with history—has folded. The terrestrial twist of the global denies history the proper spacing it needs in order to separate “back then” and “over there” from “right now” and “right here,” to cite Denise Ferreira da Silva.13

As the hybrid nation/colony of a settler state, Australia exhibits this contrapuntal (parallel yet interwoven) dynamic in its current pioneering advancement of bordering technologies. These operate on two fronts to secure the accumulation of wealth against the governance of the noncitizen: (1) the qualification of citizenhood in justifying the exceptional and punitive treatment of aboriginal people, up to and including the deployment of defense forces (imperial frontier); and (2) in the divesting of obligations of care towards those seeking to migrate or to claim asylum (global frontier).

The repercussions of these new arts of dis/possession are felt throughout the intimate politics of Australian oikonomia (householder and intimate politics, via Mitropoulos). They self-perpetuate a punitive attitude toward the poor and the moral policing of the Racial and Colonial Other.

Far from an outlier case, Australia’s innovations in this realm impact the global order as the United Kingdom borrows Australian “workfare” policy prototypes in penalizing its own poverty classes;14 as Australia’s reliance on third countries for refugee processing produces flow-on effects throughout Southeast Asia; and as European Frontex-administered island “hotspots” increasingly resemble Australian offshore detention, albeit more in their effort to filter and select a small number of “worthy” arrivals than in the exemplary cruelty of the Australian deterrence model.15

The shift from the imperial to the global frontier denotes a shift toward value accumulation in the leveraging of “marginal productivity.” An economic term initially associated with von Thünen, marginal productivity is a concept that may encompass many of the present-day tools of finance, such as the asset-backed securities that precipitated the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis. These margin practices may take the form of a yield to waste calculus of Earth and environment. Such is the case in the “exceptional mining leases” executed by sovereign debt-crisis states, e.g., Greece and Portugal, by which mining companies, such as Canada’s Eldorado Gold, exploit trace amounts of mineral using new high-intensity and high-contamination extraction technologies.

The logic that cuts across both the imperial and the global frontier is that of extraction—the technologies and ideologies of separating “value” from “undifferentiated mass,” to borrow the terms of an Australian court ruling over mineral versus non-mineral sands.16 The drive to separate “compliant” from “noncompliant” citizen doubles as a means of separating mineral-rich land from sovereign peoples. This same drive is echoed in the spectacle of German journalists sifting through the mass data of the Panama papers leak seeking criminal cases, and in Frontex EU agents sifting through arrivals for “innocent” or “worthy” cases. In this frontier logic of the new arts of possession, the proper order of justice and rightful ownership is resolved through the identification of exception, and in backgrounding the normative mass.

To receive the message recorded in the Forsters’s journal—transmitted by a Kanak man over two centuries ago—is to recognize the depth of the extractive cut in (the) time of the frontier. It is to apprehend in that performance-image back then the image-message right now, given by Waanyi artist Gordon Hookey—for example—in defiance of separation, and drawn with the line:

“They Want Our Spirituality But Not Our Political Reality. The Peddlers of Hoogah Bhoogah. The Perpetrators and Perpetuators of Cultural Colonialism.”

Georg Forster, Nicholas Thomas, and Oliver Berghof, A Voyage Around the World (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000).

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, “Interview: Forced Closures,” L’Internationale, June 26, 2015 →.

Ibid.

Angela Mitropoulos, Contract and Contagion (New York: Minor Compositions, 2012), 92.

The entire sorry chronicle of Meston’s tour—which ended in his abandoning around Melbourne the group that he had taken from various north Queensland peoples—is catalogued in the extensively illustrated publication Wild Australia: Meston’s Wild Australia Show 1892–1893, eds. Michael Aird, Mandana Mapar, and Paul Memmott (Southport: Keeaira Press, 2015).

Fabian’s term for this is a “denial of coevalness,” or the denial of being together in time, by which the ethnographic Other is regarded as static and unchanging, and thus available to be studied. Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment: Social Belonging and Endurance in Late Liberalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 36.

Élisée Reclus, 1871.

McKenzie Wark, “The Vectoralist Class,” in “Supercommunity,” special issue, e-flux journal 65 (May 2015) →; and Wark, “The Vectoralist Class, Part II,” e-flux journal 70 (February 2016) →. Rosalind C. Morris, “Accidental Histories, Post-Historical Practice?: Re-reading Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance in the Actuarial Age,” Anthropological Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 581–624. Lorraine Daston et al., How Reason Almost Lost Its Mind: The Strange Career of Cold War Rationality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Johann Heinrich von Thünen, cited in David Harvey, “The Spatial Fix: Hegel, von Thünen and Marx,” Antipode, vol. 14, no. 3 (1981): 3.

Ibid.

“Secret Instructions to Lieutenant Cook July 30, 1768,” Museum of Australian Democracy →.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, The Racial Event: That Which Happens Without Time, forthcoming 2016.

For the influence of Australian 2006 workfare platforms such as the “Mutual Obligation Initiative” and “Welfare to Work” on UK policy, see S. Wright, G. Marston, and C. McDonald, “The Role of Non-Profit Organisations in the Mixed Economy of Welfare-to-Work in the UK and Australia,” Social Policy & Administration, vol. 45, no. 3 (2011): 299–318. Layering this with 2006 legislation anticipating the Northern Territory intervention with the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Amendment Act 2006 (ALRAA) summarized as “the principal objectives of this Bill are to improve access to Aboriginal land for development, especially mining,” see Rebecca Stringer, “A Nightmare of the Neocolonial Kind: Politics of Suffering in Howard’s Northern Territory Intervention,” Borderlands, vol. 6, no. 2 (2007) →.

For a report on the Lampedusa “hotspot” current at the time of writing, see G. Garelli and M. Tazzioli, “The EU hotspot approach at Lampedusa,” Open Democracy, February 26, 2016 →.

Unimin Australia Limited v State of Queensland (2010) QCA 169. Supreme Court of Queensland transcript →.

Subject

This essay was composed within the framework of the art commissioning and research project Frontier Imaginaries and the forthcoming launch exhibition “No Longer at Ease” at the Institute of Modern Art (May 14—July 9) and “The Life of Lines” at the QUT Art Museum (May 14–August 14). Thanks are made to Denise Ferreira da Silva’s supervisory X-ray specs; to Anjalika Sagar in first drawing attention to Don’t Touch the White Woman and the gentrification of the soul; to Michael Aird in reading the economies of frontier photography; and to Rachel O’Reilly for early pointers toward and beyond the Marxian horizon.