Continued from “Walid Raad’s Spectral Archive, Part I: Historiography as Process”

… we can no longer simply explain or simply cure.1

A city, perhaps like a person, remembers the most when confronted with its destruction. The aftereffects of trauma are a different story. They frequently give rise to individual and collective amnesias, along with the psychological symptoms that congeal when a traumatic experience is too painful for consciousness to address directly. In this sense, symptoms are strange documents. They are usually synonymous with a narrative—however fractured, however distorted, however unreal—that seeks to make sense of an event that carries within it something fundamentally inexplicable. Trauma is a violent transmission of the unknown, oftentimes in the service of something larger and more inscrutable than the event itself. Much of Walid Raad’s art investigates not the failure of images to represent traumatic events but the refusal of the real to inscribe itself as a legible image. It’s a subtle difference, one rooted less in conceptual art strategies (though Raad’s work is filled with these) and more in the complex registering of the effects of traumatic historical events.

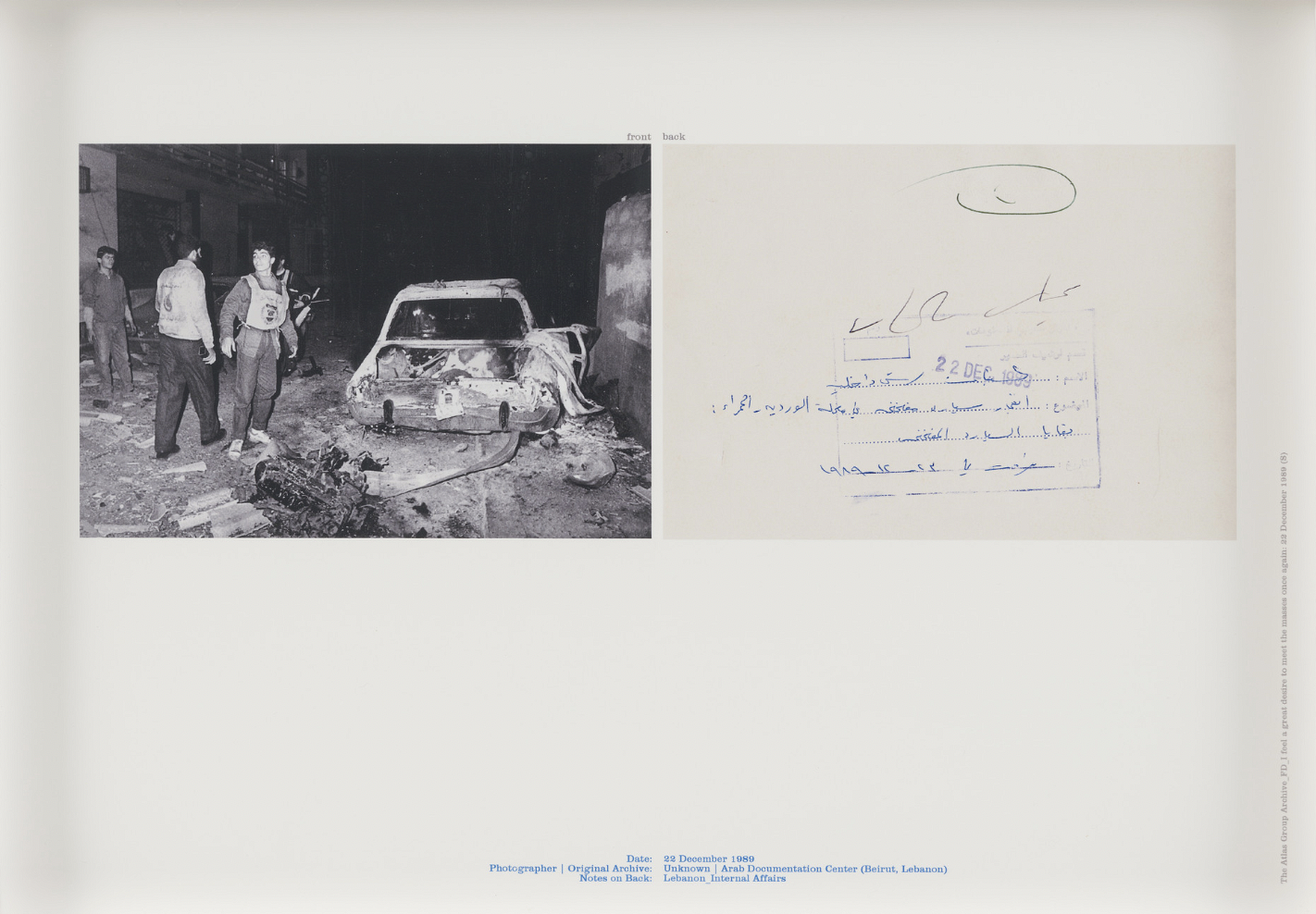

In this model, historiography becomes the writing of symptoms, and symptoms are repetitively repressive structures. As a symptomatology of indiscriminate warfare, Raad’s serial car bomb projects are consciously failed attempts to locate either the disease or its cure. My neck is thinner than a hair: Engines (2001/2000–03) builds on the earlier Notebook volume 38: Already been in a lake of fire (1991/2002) to reproduce one hundred found and appropriated photographs of the only car part to survive relatively intact after detonation—the engine. (Here and in the following, first dates are attributions by The Atlas Group; the second refer to Raad’s production of the work. Artworks with only one date are not part of The Atlas Group’s “official” archive.) Unlike Notebook volume 38, this slightly later series expands the frame to show the immediate environment after a car bomb has exploded: a small blast crater, soldiers or officials of some sort on the scene, consistently quizzical looks on the faces of bystanders. Each black-and-white photograph sits directly to the left of a reproduction of its reverse side, which is usually marked with official stamps, dates, the photographer’s name, and notes in Arabic—most all of which seems to have been added by the archives where Raad researched the images.

He floats these two adjacent images on an expanded white background, at the bottom of which appears basic information about the photograph and the details on its reverse side, though not nearly as thoroughly as in Notebook volume 38 or Notebook volume 72: Missing Lebanese wars (1989/1998). Rather, the image is left to fend hopelessly for itself. The one hundred 23 × 32 cm prints are arranged in a tight grid featuring five rows of twenty each, an installation decision that among other effects augments their repetitious quality (and relates the piece to conceptual-photo works such as Martha Rosler’s groundbreaking The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems [1974–75]—right down to Rosler and Raad’s shared use of diminutive lowercase titles that de-emphasize the autonomous art object). In Raad’s explanatory note for the project, he writes, “During the wars, photojournalists competed to be the first to find and photograph the engines.”2 Like the historians in Notebook volume 72, they can never arrive on time. Rather, they appear after the fact to help gather data about a situation that in the final analysis remains elusive. Similarly, Raad is unable or unwilling—conditions that in post-traumatic situations become partially blurred—to register the full experience of the wars, even as someone who experienced them firsthand.

The Atlas Group/Walid Raad, My Neck is Thinner Than a Hair: Engines (detail), 1996–2004. One hundred pigmented inkjet prints. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Fund for the Twenty-First Century. Copyright: Walid Raad.

1. Secrets in the Open Sea

Testimony and witness, the two standard tropes of documentary photography (and especially war photography), have either gone missing or are under the severest duress in Raad’s work.3 In Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art, Jill Bennett differentiates between “narrative memory” and “traumatic memory.”4 Bennett argues that the representation of traumatic experience necessitates the creation of a new visual language that downplays testimony, incorporates fictional elements, and utilizes affect in order to move our encounter with trauma “beyond the realm of the interior subject into that of inhabited place, rendering it a political phenomenon”5; in this place, “perpetrators, victims, and bystanders are all compromised by a cycle of violence.”6 This pastiche of truth-claims captures the general and widespread symptomology of trauma. To record this condition, The Atlas Group vacates the authority of the artist, the historian, or the spokesperson for the underrepresented, in favor of the kind of personal cosmology that makes Lebanon kin with other sites of unremitting disaster: Baghdad … Grozny … New Orleans … Fukushima …

Raad’s video We can make rain but no one came to ask (2003/2006) explicitly signals the formation of such a traumatic semiotics during an opening sequence in which dust clouds transform into stars that then form a constellation of car parts. “What I like about this piece is that it is literally creating a cosmology,” Raad says in a New York Times profile, “It’s not like people were idiots when they looked at the stars and told stories about them 2,000 years ago. Now there are other stories. Now is the fetish moment of the car engine.”7 The video captures the failure of the image to effectively witness history (and an element of failure in witnessing itself) as it disassembles—at times, dissembling—the survivor’s tale in order to illustrate how even this seemingly immediate and authentic mode of expression is already mediated.

At one point, Raad briefly planned to assemble extensive files and construct small-scale dioramas for each of the wars’ 3,641 car bombs. One result is the sculptural installation I was overcome with a momentary panic at the thought that they might be right (1994/2005), attributed to either topographer Nahia Hassan or car bomb expert Yussef Nassar, depending on the exhibition, installation, and other work with which it appears. For this reason its dates vary; its earliest incarnation appears to have been for a cultural program accompanying the 2004 Athens Summer Olympics. A spotlit white disc—or discs—made of dense foam, the sculpture is punctured by holes of different sizes meant to map every car bomb exploded during the war. It’s a burden light enough to be carried almost anywhere.

We can make rain but no one came to ask is the result of investigations Raad undertook with writer Bilal Khbeiz and architect and visual artist Tony Chakar into a single car bomb detonated in Beirut on January 21, 1986. Like the ripple effects of damage that spread across the city with each car bomb explosion, the video is perhaps Raad’s most expansive vision of Beirut during and after the war. Its catalogue of by-now familiar motifs from The Atlas Group—archival documents, car bombs, architecture, the color blue, passionate yet quixotic chroniclers of the war—extends to represent other devastated cities confronted with the complicated dynamic between remembering and rebuilding. Less a video per se, the piece more closely resembles a seventeen-minute digital slideshow consisting of hundreds of stitched images and a haunting soundtrack. Its composition from still images is not unlike La Jetée (1962) by Chris Marker, whose essay films have clearly influenced Raad’s work. Its initial screen announces that the work is meant to document the tireless efforts of Georges Semerdjian, “a fearless photojournalist” killed in 1990, and Yussef Bitar, “the Lebanese state’s leading ammunitions expert and chief investigator of all car bomb detonations.”

Somewhat unexpectedly for those familiar with The Atlas Group’s motley cast of fictional characters, both are actual historical figures, though seemingly less likely is a declaration on the next screen stating that they collaboratively researched the car bomb in question. The reference to real participants, one of whom lost his life documenting the war, indicates that the video will partly function as an elegy, a relatively rare mode in Raad’s work despite its persistent concern with loss. (This elegiac tone also appears in the seven-and-a half-minute film of repeating sunsets shot from Beirut’s seaside corniche, I only wish that I could weep [2002/2002].) The two opening text captions are followed by roiling plumes of fire and smoke seen through a thin horizontal slit on a black screen that gives way to the sound and images of ocean waves as the perspective opens onto a panoramic shot of Beirut jutting into the Mediterranean. The screen then goes dark, voices on the soundtrack become distressed, and the previously mentioned constellation of car parts slowly takes shape as sirens fill the air.

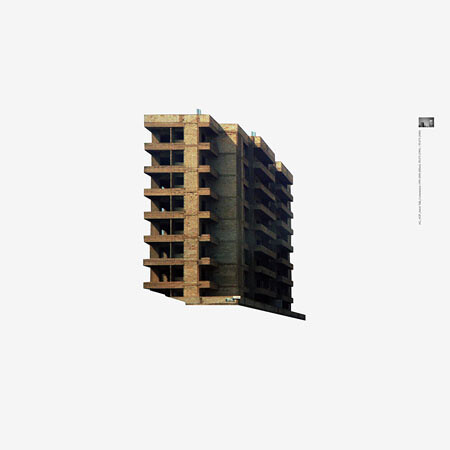

A photo of Bitar is introduced before an image of car bomb carnage appears followed by short clips of a rebuilt Beirut along with birdsong and traffic noise. Next is an extended focus on architecture, which Raad depicts with moving images, skeletal renderings, and cropped photographs—sometimes superimposed on each other. The architectural drawings are ghostly versions resembling ones found in the master plans for Beirut’s rebuilding.8 Throughout the video, Raad splits the screen into three quadrants so that a car or pedestrian moving out of one part vanishes into another. The civil wars confined people in Beirut and its suburbs to their immediate neighborhoods within the larger demarcation (indicated by the Green Line) separating the Muslim-dominated western area of the city from the Christian eastern section. Raad’s work refuses to allow a unified view, and the urban landscape it depicts is never more than a patchwork. In We can make rain but no one came to ask, this fracturing occurs on multiple formal levels: from its segmented screen to its nonlinear editing; from its combination of still images and short video clips to its associative logic; from its constant fades and dissolves to its digitally manipulated perspectives.

The screen goes blue after the passage through architecture, the color of Beirut unmoored between sky and sea. Then sounds of construction and images of signs and storefronts scroll by. This is followed by two headshots, one solarized, one not, of Semerdjian that introduce an extended stretch of car bomb photos similar to the ones in My neck is thinner than a hair: Engines but with an even broader view of the street and surrounding buildings. There are also a number of images of charred bodies—to my knowledge the only moment in the entirety of Raad’s oeuvre when victims of the wars appear, which gives these pictures an added gravity. It’s possible (these kinds of concrete details can be difficult to verify in Raad’s work) that these photographs are from the last roll of film Semerdjian shot before he was killed four years after the car bomb documented in the video.9 Moreover, it is difficult not to notice the resemblance to images of the World Trade Center site in the days following September 11, 2001. The soundtrack goes silent, as these ghosts—of people and of buildings—seek recognition amid the earlier visual and aural evidence of rebuilding. Contemporary Beirut again returns with a camera pan of digitally fossilized architecture before the video ends with shots of buildings, trees, and storefronts.

The storefronts recall Raad’s first attempt to systematically document the architecture of Beirut, The Beirut Al-Hadath archive, with its catalogue of storefronts evoking Eugène Atget’s photographs of Paris. Raad published the project in Rethinking Marxism in 1999, and it foreshadows many of the strategies that would become associated with The Atlas Group, which was established around the same time:10 an imaginary foundation established in 1967, the year of Raad’s birth; a repository for documents made by other people; a fake list of funders (including a Mr. and Mrs. Fakhouri); a series of grainy, black-and-white photographs with somewhat elusive captions and dubious provenance; a pretend exhibition; and an introductory explanatory text written by a fictional expert named Fouad Boustani. Raad writes: “Al-Hadath critically confronts and examines issues of power, space, time, and trauma as they were and are manifested in the history of Lebanon and of the Lebanese civil war, in photographic and documentary practice.”11 Important to note here is that the accompanying photographs evidence very little about the wars—Raad would soon come to pluralize “civil war”—while simultaneously functioning as pleas against forgetting.

2. The Withdrawal of Tradition

The seeds for The Atlas Group had been sown, not only in terms of its general format but also its growing obsession with architecture. Along with Atget—whose influence is “explained” by Boustani as a critique of the earlier French colonial presence in Lebanon—Raad’s work owes much to Walker Evans’s crisp formalism as well as Bernd and Hilla Becher’s serial typologies. Like the Becher’s project—and perhaps Evans’s too—Raad’s art contains a degree of sentimentality overlaid with an exacting formalism. Like Benjamin’s Arcades Project, Atget documents a Paris that arrives and vanishes simultaneously, just as Raad and Al-Hadath capture Beirut somewhere between disappearance and renovation.

More ambitious and fully realized, Sweet talk: The Hilwé commissions (1992–2004/2004) finds Raad redeploying the Beirut Al-Hadath archive conceit in which numerous photographers—dozens for Sweet talk, one hundred for Al-Hadath—are sent out across the city to photograph architectural conditions as they existed before, during, and after the wars. Raad carefully crops the photographed building from its immediate environment (much as he did with the cars in Notebook volume 38), frontally aligns it to have a proper architectural perspective, floats it on a white background, and inserts in the upper-right portion of the print a miniature, almost indecipherable black-and-white version of the original unmanipulated image, rotated ninety degrees to the left. As Ulrich Baer writes, “If we analyze photographs exclusively through establishing the context of their production, we may overlook the constitutive breakdown of context that, in a structural analogy to trauma, is staged by every photograph.”12 Raad’s formal precision shelters these edifices while simultaneously interrupting their history to diagram the impact of trauma on our sense of context.13

This is not unrelated to Jalal Toufic’s idea of “the withdrawal of tradition past a surpassing disaster,”14 which has inspired much of Raad’s more recent work, especially his first large-scale project after The Atlas Group: Scratching on things I could disavow. For Toufic and Raad, this “withdrawal” effects not only history and tradition but also objects in the world, including buildings (as in The Beirut Al-Hadath archive and Sweet talk: The Hilwé commissions) and artworks—Raad’s own and others. Paradoxically, acknowledging this withdrawal is the only way to safeguard what has already disappeared. For Raad and many other artists of his generation in Lebanon, this is as much a question of form as it is of content, i.e., the utilization of war imagery. The care shown toward these forms is synonymous with ministrations for what has vanished.

As Eduardo Cadava explains in Words of Light: Theses on the Photography of History:

The present no longer struggles to lead knowledge, as one would lead the blind, to the firm ground of a fixed past. Instead the past infuses the present and thereby requires the dissociation of the present from itself. In other words, the past—as both the condition and caesura of the present—strikes the present and, in so doing, exposes us to the nonpresence of the present. If it is no longer a matter of the past casting its light on the present or of the present casting its light on the past (N 50 / GS 5:578 [Cadava’s citation is to Benjamin’s writings]), it is because the past and the present deconstitute one another in their relation. The coincidence of this exposure and deconstitution defines a political event, but one that shatters our general understanding of the political. It tells us that politics can no longer be thought in terms of a model of vision. It can no longer be measured by the eye.15

Scratching on things I could disavow disrupts vision in the service of something like Cadava’s antivisual politics by manifesting Toufic’s notion of withdrawal: from the literally miniature museum of artworks collected/produced by The Atlas Group (Section 139: The Atlas Group [1989–2004])—imagine a less portable version of Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise—to the nearly invisible Arabic and English script of Index XXVI: Artists (2009), to the formal reductivism in the series of prints collectively titled Appendix XVIII: Plates (2009), to the absent artworks in On Walid Sadek’s Love Is Blind (Modern Art Oxford, 2006) (2009). Throughout Scratching on things I could disavow, artists and artworks have disappeared. So, too, has the political and historical imagery that rooted The Atlas Group—for all of its intentional elusiveness—in the Lebanese civil wars. Whereas Raad once compulsively preserved this imagery, his focus has now turned to artistic traditions and aesthetic forms in Lebanon and the larger Middle East. The prints in Appendix XVIII: Plates reproduce—albeit obscurely—the colors, fonts, and graphic design of books, catalogues, press announcements, and other materials used in the exhibition and dissemination of twentieth-century Middle Eastern art. In Index XXVI: Artists, it’s the color red that has at some future point withdrawn.

3. New Hysterical Infrastructure

Interruption, whether historical or psychic, is a noninstrumental intervention in Raad’s work. With an almost willful absurdity, he’s stamped Toufic’s “surpassing disaster” on his art in order to assert that it’s not the artist who is causing history—or, in his latest project, artworks from the Middle East—to withdraw, but conditions themselves. “It is the world itself that acts this way and I’m just present,” as Raad tells H. G. Masters in a feature for ArtAsiaPacific magazine. “It’s getting away from a psychic model to a more phenomenological model … It’s no longer about mediation.”16 In the collective amnesia that is a response to the massive shared trauma of the civil wars, history and culture have withdrawn, literally, and the task of the artist, according to Toufic, is to register this withdrawal. Yet both Raad and Toufic are aware that a generalized metaphysics of disaster is much more amenable to reactionary forces than progressive ones, specifically Christian, Islamic, and Jewish sacro-political fundamentalism. All three helped fuel the Lebanese civil wars, and continue to destabilize the country and the Middle East. As Derrida said of Benjamin’s obsession with destruction: “One may well ask what such an obsessive thematic might signify, what it prepares or anticipates between the two wars, all the more so in that, in every case, this destruction also sought to be the condition of an authentic tradition and memory.”17

Perhaps in response to this, Raad insists on concretely framing the work in Scratching on things I could disavow as a mode of institutional critique, and he describes in performances, talks, and interviews his tracking and gathering of information related to a suddenly booming arts infrastructure in the Middle East. For instance, Beirut didn’t have a traditional white-cube commercial art gallery until Sfeir-Semler Gallery (which represents Raad in Lebanon and Germany) opened a gleaming space in 2005.18 In the summer of 2009, a new Beirut Art Center was profiled in The New York Times.19 The Artist Pension Trust has expanded into the Middle East, assembling artists and art from the region for its fund, and there are now numerous biennials and art fairs proliferating across the Arab world. In Abu Dhabi, the Guggenheim is building its largest branch—designed by Frank Gehry—in terms of square footage, and has established a sizable acquisition budget for purchasing work from the Middle East to fill it. The Louvre is also opening a museum in Abu Dhabi, and Zaha Hadid is designing the city’s performing arts center, all of which—and more—Raad mentioned in his talk-performance Scratching on things I could disavow: Walkthrough:

Of course these themes emerge naturally from Raad’s previous work with The Atlas Group addressing the rebuilding of Beirut’s infrastructure in the wake of the civil wars. This, too, was a highly contentious process, examined at the time and since by various individuals and groups both internal and external to Lebanon. In a 1997 article published in Critical Inquiry, Saree Makdisi describes how then-Lebanese prime minister Rafic Hariri’s construction firm Solidere spearheaded the redevelopment of downtown Beirut without significant public input, and proceeded to destroy more of the area in a single year than the wars had ruined in the previous fifteen. Moreover, it did so before a final reconstruction plan had been approved:

Not only were buildings that could have been repaired brought down with high-explosive demolition charges, but the explosives used in each instance were far in excess of what was needed for the job, thereby causing enough damage to neighboring structures to require their demolition as well … It is estimated that, as a result of such demolition, by the time reconstruction efforts began in earnest following the formal release of the new Dar al-Handasah plan in 1993, approximately 80 percent of the structures in the downtown area had been damaged beyond repair, whereas only around a third had been reduced to such circumstances as a result of damage inflicted during the war itself.20

Thus, when Raad documents pockmarked and crumbling buildings in Let’s be honest, the weather helped, or We can make rain but no one came to ask, or Sweet talk: The Hilwé commissions, he isn’t simply registering damage caused by the war, but also damage caused by the efforts to repair the damage caused by the war. Such events provide a historical and materialist explanation for the small role cause and effect play in Raad’s world, allergic as it is to forms of instrumentality. Rather, Raad’s latest projects address ongoing tears in the social fabric and structural flaws within history itself. Whereas earlier artworks by The Atlas Group registered these effects on individual and collective psyches, architecture eventually became the edifice on which they were inscribed.

In interviews and performances, Raad has characterized his work as a series of “hysterical symptoms”: “We urge you to approach these documents as we do, as ‘hysterical symptoms’ based not on any one person’s actual memories but on cultural fantasies erected from the material of collective memories.”21 Although, as he mentions in the ArtAsiaPacific feature, he’s started to shift this discourse away from the psychological. A good example of an early project that combines a focus on symptoms with the political economics of postwar Beirut is Secrets in the open sea (1994/1999), which consists of six large (111 × 173 cm), lushly blue monochrome prints surrounded by a thin white border. In the bottom right-hand corner of each print is a tiny faded black-and-white photograph. In his description of the work, Raad states that twenty-nine prints were discovered in 1993 under the ruins of Beirut’s central business district during the area’s demolishment in preparation for rebuilding. Given to The Atlas Group, six of the prints were then sent to overseas photo labs for examination. It turns out that embedded within the blue images are group portraits—reproduced in miniature at the bottom of the print—of men and women who, The Atlas Group discovered, “drowned, died or were found dead in the Mediterranean between 1975 and 1991.”22

An even earlier version, entitled Miraculous beginnings (1997), precedes The Atlas Group.23 Accompanied by a fictional archive and consisting of grey instead of blue monochromes, it exists as one of Raad’s earliest publicly disseminated solo works (Raad appropriated the title a couple years later for one of Fakhouri’s two short films). In both iterations, the exhumed images are of suited men and women wearing dresses, signaling middle- and upper-middle class status, i.e., business people, politicians, civic leaders. If the members of this group constituted a relatively cohesive social core that crumbled during the wars, they also serve as symbolic representatives of a functioning nation-state. This political legitimacy, Raad seems to say, is as much imagined and projected as it is real. Most modern claims of sovereignty are. In an uncanny doubling, the documented absence of members of this governing coterie was only discovered during the razing of downtown Beirut by a related group claiming to represent the nation, but who in reality is another example from Lebanon’s recent history of private interests triumphing over the collective good.

Is this why Raad specifically contextualizes the rediscovery of a drowning fantasy within the postwar leveling of downtown Beirut? As Raad buries and then reanimates Lebanon’s civic and business leaders, there’s an undercurrent of violence to the work’s seductive surface. Yet it’s a violence directed against violence. As Miriam Cooke explains in her essay “Beirut Reborn: The Political Aesthetics of Auto-Destruction”: “After the Israeli invasion of 1982 the increasingly visible involvement of war profiteers changed the conditions of possibility for telling a moral story.”24 For Cooke, both morality and narrative have been made impossible by the war—but this impossibility persists after its conclusion. The postwar profits to be reaped during reconstruction similarly trumped public memory, mourning, and the proposal of alternative narratives for postwar Lebanon. Raad’s response is the creation of imaginary and symbolically charged “representational spaces” that seek to disrupt the rationally ordered “representation of space” imposed by the master plan for a new Beirut: “To be more precise, and to use the terminology introduced earlier: in the spatial practice of neocapitalism (complete with air transport), representations of space facilitate the manipulation of representational spaces (sun, sea, festival, waste, expense).”25 Yet no amount of building, and no amount of commentary, will explain away the blue.

In Raad’s early work, convoluted oedipal relations frequently entailed authority’s demise—whether the artist’s own, Fakhouri’s, or that of the ciphers buried beneath the surface of Secrets in the open sea. Yet this authority—including Raad’s—continues to reassert itself. The initially hidden individuals in business dress mimic the functioning of repression and its slow exposure by psychoanalysis. Sarah Rogers goes so far as to compare Raad’s role to that of a psychoanalyst.26 Raad has repeatedly argued that the psychological symptom is very much real, and this reality is reflected by its repetition on a more strictly formal level.27 The repression wrapped in fantasy makes the figures’ unexpected surfacing all the more haunting. After all, Secrets in the open sea is a series of so-called documentary prints that for all their splendor undermines conventional modes of vision and witnessing. As an attack on representation, it manifests a psychogeography of loss amid the irruptions of a strange sublime,28 while its nonrepresentational monochromes counter the real estate speculators’ linear blueprints.

4. Truth and Reconciliation

Time helps, in ways that are wholly mysterious, to complete the process of forgiveness, though never of reconciliation.29

A city, perhaps like a person, can only be at war for so long. Sigmund Freud may have posited the psyche’s death-drive toward inanimate matter, but the desire in any organism—a person, a city—to remain animate is very strong. The ruling powers in postwar Lebanon decided against convening a truth and reconciliation commission. Instead, its parliament passed an amnesty law in 1991 pardoning most war crimes, which in turn allowed prominent figures in the civil wars to become part of the country’s new government. Much has been written concerning the effectiveness of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the most famous of the dozens of such commissions established around the world. If these have taught us anything, it’s that meaningful reconciliation is contingent upon acknowledging difference. Not the plurality of identities in a multicultural society, but the difference between victimizer and victim, oppressor and oppressed—while recognizing that even within the most repressive system, as within marginalized communities, these distinctions can become blurred.

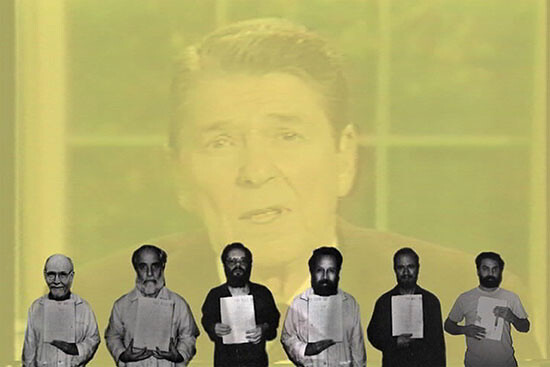

We see this in Hostage: The Bachar tapes (#17 and #31)_English version (2000/1999). The eighteen-minute video claims to be a portrait of a Lebanese man named Souheil Bachar held hostage for ten years during the civil wars, and who for a few months in 1985 was kept with well-known Western hostages Terry Anderson, David Jacobsen, Martin Jenco, Thomas Sutherland, and Benjamin Weir. (Bachar is fictional, although there seems to have been an Arab hostage briefly held with the Western ones.30) When shown as part of a performance, the video allows Raad to discuss the geopolitics of the “Western hostage crisis” whereby the United States covertly sold arms to Iran in exchange for the release of hostages held in Lebanon, and used the profits to fund the Reagan administration’s illegal support of the Contras in Nicaragua.31

The video focuses on Bachar’s time with the Western hostages, culminating in a fairly graphic description of their attraction to and repulsion by his physical body. Perhaps the least visually polished of Raad’s work, the piece at times mimics the kind of videotaped statement a captive makes, complete with taped-up flag or piece of fabric on the back wall. After their release, the Western hostages had access to commercial publishers and movie producers eager to exploit their stories; Bachar had The Atlas Group, a cheap video camera, and an imaginary archive.

As in the horse race-based Notebook volume 72, Raad is very much interested in how histories are written; but in Hostage, he illuminates the power behind these narratives, whether the willful failures of Congressional committees investigating the Iran-Contra affair to engage with the larger ramifications of US foreign policy,32 or the influence of the mainstream media over public discourse and memory.33 As scholar of trauma literature Kalí Tal writes (at least five years before 9/11): “The battle over the meaning of a traumatic experience is fought in the arena of political discourse, popular culture, and scholarly debate. The outcome of this battle shapes the rhetoric of the dominant culture and influences future political action.”34 Yet Raad is not after the true story, or even a counter-story. The person who plays Bachar is a famous actor in Lebanon, which would instantly alert viewers there that they were watching a piece of sustained artifice—and satire (Raad’s work has a morbid sense of humor, as conveyed in his titles, but it’s rarely satirical). Moreover, there are various infelicities in the video’s translation of Bachar’s narrative into English. Bachar asks that this English voiceover be female, and, given the chance to tell his own version of events, Bachar is constantly interrupted by the editing and purposefully rudimentary technology. It’s essential to try and give a voice to the politically and historically marginalized; but even this, Raad implies, is a complex, mediated, and difficult form of witnessing.

If truth doesn’t necessarily lead to reconciliation, as Rustom Bharucha wrote alongside the 2002 Documenta in which Raad’s work appeared and garnered international attention, then the artist’s fictional devices might be understood as an alternative approach, one that approaches reconciliation outside a juridical economy of truth.

The Atlas Group/Walid Raad, I might die before I get a rifle—Device II, 1998-2000. Archival inkjet prints on archival paper. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg/Beirut.

5. Caring for Violence

Thus other works by Raad have again moved backward in time from the postwar period to the war itself. We decided to let them say, ‘we are convinced,’ twice (2002/2006), a series of photographs produced from surviving but damaged negatives Raad shot as a teenager in 1982 during the Israeli invasion, features the most conventional war imagery he has produced: smoking buildings, fighter jets streaking across the sky, Israeli soldiers napping against their tanks in Christian East Beirut. In Let’s be honest, the weather helped, Raad placed fluorescent-colored dots of different sizes on street-level photographs to indicate where he discovered stray bullets. In the photographic prints Scratching on things I could disavow (1992/2008)—another recycled title—cutouts of collected bullets, shrapnel, and small explosives are placed in neat rows next to short descriptive phrases, ranging from “trade with cousin” (for a new bullet) to “I am convinced that this did not kill anyone” (for a piece of shrapnel)—an odd moment of conviction in Raad’s incessantly questioning art, and one that finds kinship with Baer’s formulation that “photographs can capture the shrapnel of traumatic time.”35

I might die before I get a rifle (1990/2008) purports to be twelve large color images printed from a CD-ROM made by a previous member of a Lebanese Communist militia whose job after the war required him to collect and photograph weapons and unused ordnances: grenades, artillery shells, plastic explosives, bullets. I might die before I get a rifle is among Raad’s least visually mediated pieces, evoking the look of digital snapshot photography and involving very little of the cut, paste, and collage methodology of his other sets of photographic prints. Raad may be moving away from work that engages the psychology of trauma, but the weapons of war featured in each of the twelve photographs are treated and depicted as fetish objects par excellence. A striking 160 × 203 cm tightly cropped shot of a latex-gloved hand holding a 50 mm shell is as fastidiously presented as the miniature smoke plumes rendered in serial Minimalist fashion in Oh, God, he said talking to a tree (2006–08).

Many of Raad’s works are accompanied by an explanatory text, whether they’re presented in an exhibition or print publication format. The one for Oh, God, he said talking to a tree is incorporated into the work as a separate print, the last of thirty-one. It states that the explosions are from the summer of 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel, and emphasizes the absurdity in being forced to choose between the two opposing forces. (The text, a version of which appeared in the October 2006 issue of Artforum, doesn’t mention that the photographs were appropriated from various media sources.36 For Raad’s on-the-ground reporting of the war—he was in Beirut with his family when fighting broke out—see his published dialogue with Silvia Kolbowski.37) This refusal of partisanism is crucial to Raad’s work, while also distinct from neutrality. Despite his (imaginary) ordeals, Bachar never demands justice or retribution for his ten years in captivity, perhaps wary of the laws to which these notions are tied. Violence, as Benjamin argues, “is the origin of law,” and frequently its result.38 Or perhaps Bachar understands that, as Upendra Baxi has beautifully written, “constitutional decision or policy-makers present themselves as being just, even when not caring … It is notorious that constitutional cultures remain rights-bound, not care-bound.”39 A similar sense of care—even toward violence—can be found in Raad’s work. At the very heart of its many fictions and prevarications is a sense that language and image don’t do justice to the event. He stresses this point by quoting Toufic’s book Undeserving Lebanon not once but twice in an interview with Seth Cameron in the Brooklyn Rail that coincided with Raad’s MoMA retrospective: “Is trying to understand the event that happens to me (socio-economic, historical, political, etc.) enough? No. Is not understanding it but it in an intelligent and subtle way enough? No. Is trying to render justice enough? No, justice is never enough. We have to additionally feel that we merit the event that happened to us.”40

Raad’s work bypasses justice, truth, and reconciliation for expiation—a ghostly expiation, or, more precisely, an expiation of ghosts.

6. Between Past and the Future

Why is there so little of the present in Raad’s art? Where are its human occupants? The few that are seen, as in the video We can make rain but no one came to ask (its very title an invocation of the past by the present), quickly disappear from the frame. Justice, truth, and reconciliation can exist without care, but there’s no expiation without care. Along with being a textbook sign of the traumatic symptom, the constant repetitions in Raad’s art are wedged between conflict and reconciliation. While at times they may resemble transcendence, they instead create the space (and time) for a different way of understanding guilt and expiation. In a powerful reading of Benjamin’s “early aesthetics”—where the expressionless stands against retributive justice—in relation to his “Critique of Violence” essay, Judith Butler writes: “This power of obliteration constitutes a certain kind of violence, but it is important to understand that this is a violence mobilised against the conception of violence implied by retribution. Understood as ‘a critical violence’, it is mobilised against the logic of atonement and retribution alike.”41 In Raad’s work, these historical and temporal caesuras—Toufic’s “the withdrawal of tradition past a surpassing disaster”—just as readily induce moments of profound uncertainty in their

movement away from a binary, sacrificial logic and any totalizing belief that a regulative ideal (such as justice) may be fully realized (a movement that is in my judgment desirable) toward a problematic condition of social emergency or crisis marked by the generalization of trauma as trope, arbitrary decision (or leaps of secular faith across antinomic or anomic abysses), extreme anxiety, and disorientation, if not panic.42

In this sense, it would be easier if Raad’s art were about a counterhistory to the ones written by the victors. It would be easier if Raad’s art were about the stutters and lacunae of traumatic expression. It would be easier if Raad’s art were about the failures of historical representation. It would be easier if Raad’s art were about indeterminacy countering dogmatism. It would be easier if Raad’s art were about nonjudicial justice. All of these are engaged, but none are exhaustive.

There is an additional and inexorably dark force at work in Raad’s art—a disaster of the sort about which Caruth, Toufic, Benjamin, and Maurice Blanchot43 write—beyond understanding, naming, and that certainly cannot be seen, and which in its refusal to make the distinctions upon which retribution relies asks for a burdened history to begin again, perhaps even anew, in the gaps of its traumatic returning. Or if that’s too much, too excessive, then maybe it’s also possible to consider Raad’s art as part of an ongoing transitional justice, both in Lebanon and among diverse global communities joined by the experience of historical trauma (and increasingly linked at another level by a globalized art world in which Raad’s work circulates, and which Scratching on things I could disavow partly “documents”). Lodged between the past and the future with the law still in formation, transitional justice maintains a dialogue with both until the next histories are written. Raad interrupts history to create moments of possibility and spaces of productive uncertainty, like the paths walked by Raad’s audience through his singular and endlessly generative labyrinth of work.

Cathy Caruth, “Trauma and Experience: Introduction,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 4.

Walid Raad, in The Atlas Group (1989–2004): A Project by Walid Raad, eds. Kassandra Nakas and Britta Schmitz (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Köning), 96.

Here, too, he summons Rosler’s critiques of liberal humanist documentary traditions, not only in The Bowery… itself, but in her subsequent companion essay—Martha Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography),” in Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 151–206.

Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 23–24. Dominick LaCapra makes a related distinction in Writing History, Writing Trauma between “historical trauma” and “structural trauma” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 76–78. This account also echoes Hal Foster’s descriptions of archive-based work in “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (Fall 2004):5, n. 8.

Ibid., 151.

Ibid., 18; emphasis in original.

Amei Wallach, “The Fine Art of Car Bombings,” New York Times, June 20, 2004 →

See Robert Saliba, Beirut City Center Recovery: The Foch-Allenby and Etoile Conservation Area (Beirut: Solidere, 2004), 204–272.

André Lepecki, “‘After All, This Terror Was Not Without Reason’: Unfiled Notes on the Atlas Group Archive.” TDR, vol. 50, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 97.

Walid Raad, “The Beirut Al-Hadath Archive,” Rethinking Marxism, vol. 11, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 15–29; reproduced in Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: Some Essays from The Atlas Group Project (Lisbon: Culturgest; and Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Köning, 2007), 33–47.

Raad, “The Beirut Al-Hadath Archive,” 19; Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, 37.

Ulrich Baer, Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 11.

Walid Raad, “Sweet Talk or Photographic Documents of Beirut,” Camera Austria 80 (December 2002): 43–53. One of many examples of Raad’s recycling of names, titles, files, and artworks, sometimes for the sake of expediency, and other times to further complicate the question of the document, the archive, and the artist as singular producer, this second Sweet talk should not to be confused with its initial incarnation as Sweet talk or photographic documents of Beirut (2002).

See, most succinctly, Jalal Toufic, “The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster,” in Scratching on Things I Could Disavow: A History of Modern and Contemporary Art in the Arab World / Part I_Volume 1_Chapter_1 (Beirut: 1992–2005), eds. Clara Kim and Ryan Inouye (Los Angeles: California Institute of the Arts/REDCAT, 2009), 1–53.

Eduardo Cadava, Words of Light: Theses on the Photography of History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 71.

H. G. Masters, “Those Who Lack Imagination Cannot Imagine What Is Lacking,” ArtAsiaPacific 65 (September/October 2009): 134.

Jacques Derrida, “Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of Authority,’” Cardozo Law Review 11 (1990): 1044–1045.

In a gesture of (self-)institutional critique, one of the prints in Appendix XVIII: Plates elliptically records the gallery pushing for Raad and Bernard Khoury to be included in a proposed Lebanese national pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Patrick Healy, “Face of War Pervades New Beirut Art Center,” New York Times, July 7, 2009 →

Saree Makdisi, “Laying Claim to Beirut: Urban Narrative and Spatial Identity in the Age of Solidere,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 23, no. 3 (Spring 1997): 672, 674.

Walid Raad, “Let’s Be Honest, the Rain Helped: Excerpts from an Interview with The Atlas Group,” in Review of Photographic Memory, ed. Jalal Toufic (Beirut: Arab Image Foundation, 2004), 44.

Raad, in The Atlas Group (1989–2004), 104.

Walid Raad, “Miraculous Beginnings,” Public 16 (1997): 44–53; reproduced in Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, 6–15.

Miriam Cooke, “Beirut Reborn: The Political Aesthetics of Auto-Destruction,” Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 15, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 400.

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 33, 59.

Sarah Rogers, “Forging History, Performing Memory: Walid Ra’ad’s The Atlas Project,” Parachute 108 (October/November/December 2002): 77. Psychoanalysis, along with Marxism, formed a heavy component of Raad’s graduate school studies.

See Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, “The Atlas Group Opens its Archives,” Bidoun, vol. 1, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 24.

See Toufic, “The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster,” 53, n. 64.

Walter Benjamin, quoted in Judith Butler, “Beyond Seduction and Morality: Benjamin’s Early Aesthetics,” in The Life and Death of Images: Ethics and Aesthetics, eds. Diarmuid Costello and Dominic Willsdon (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008), 73–74.

Vered Maimon, “The Third Citizen: On Models of Criticality in Contemporary Artistic Practices,” October 129 (Summer 2009): 101.

Hostage (in print) also offers an expanded geopolitical context for the piece, drawn from research Raad conducted for his PhD dissertation in the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester. This version appeared in the catalogue for Catherine David’s traveling group exhibition “Contemporary Arab Representations,” which helped introduce Raad and other cultural producers from the Middle East to the larger art world. See Walid Raad, “Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves: Excerpts from an Interview with Souheil Bachar Conducted by Walid Raad of The Atlas Group,” in Tamáss: Contemporary Arab Representations, ed. Catherine David (Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 2002), 122–137. See also Walid Raad, Beirut … a la folie: A Cultural Analysis of the Abduction of Westerners in Lebanon in the 1980s, PhD dissertation, University of Rochester, 1996.

Raad, “Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves,” 128–129; Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, 58–59.

Raad, “Civilizationally, We Do Not Dig Holes to Bury Ourselves,” 130; Raad, Scratching on Things I Could Disavow, 60.

Kalí Tal, Worlds of Hurt: Reading the Literatures of Trauma (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 7.

Baer, Spectral Evidence, 7.

Walid Raad, “‘Oh God,’ He Said, Talking to a Tree: A Fresh-Off-the-Boat, Throat-Clearing Preamble about the Recent Events in Lebanon: And a Question to Walid Sadek,” Artforum, vol. 45, no. 2 (October 2006): 242–244.

Silvia Kolbowski and Walid Raad, Between Artists: Silvia Kolbowski and Walid Raad (New York: A.R.T. Press, 2006).

Walter Benjamin, “Critique of Violence,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Schocken Books, 1978), 286.

Upendra Baxi, quoted in Rustom Bharucha, “Between Truth and Reconciliation: Experiments in Theatre and Public Culture,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 36, no. 39 (September–October, 2001), 3765.

Walid Raad, “In Conversation: Walid Raad with Seth Cameron,” Brooklyn Rail (December 2015/January 2016): 17. Jalal Toufic, Undeserving Lebanon (Beirut: Forthcoming Books, 2007).

Butler, “Beyond Seduction and Morality, 75.

LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma, 31.

Maurice Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster, trans. Ann Smock (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986).