Another conversation threw up a fascinating image: “During our regular night shifts, the general manager used to be abrasive with any worker he saw dozing. He used to take punitive action against them. One night, one hundred and eight of us went to sleep, all together, on the shop floor. Managers, one after the other, who came to check on us, saw us all sleeping in one place, and returned quietly. We carried on like this for three nights. They didn’t misbehave with us, didn’t take any action against us. Workers in other sections of the factory followed suit. It became a tradition of sorts.”

—Faridabad Mazdoor Samachar (Faridabad Workers’ News), May 20141

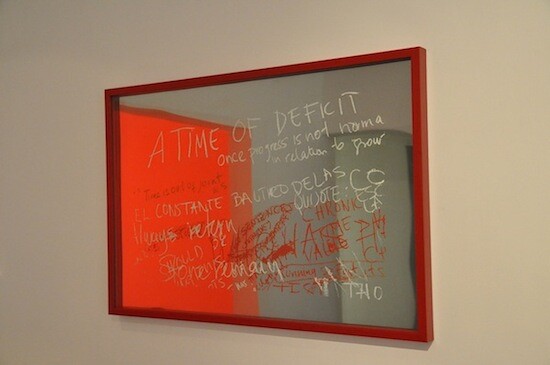

A hundred years after 1914 saw nationalism explode in an orgy of violence like the world had never seen before, we are waking up to a new reality that appears to be as repetitive as a recurring nightmare. In some parts of the world, ultranationalist parties are once again walking into the bright lights. This could be a sordid one-act play or a full-blown tragic opera, but for now, they think they hold the public in thrall.

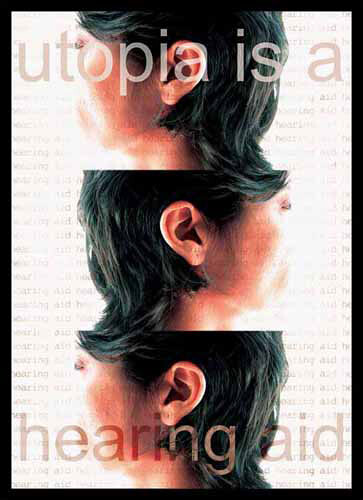

And they are singing. So loudly that the din appears to drown out every other sound. These are times when one needs a hearing aid, to listen to the murmur of other conversations. Some of these conversations may be incipient, some have never ceased. They may never cease. If they are inaudible, one has to try a little harder to hear them.

In India, the recently victorious ultranationalist “strongman” has tweeted “the good days have come” to the enthusiastic, breathless applause of a captive “eternal-growth” court. His counterparts, flashing victory signs in Europe, Russia, Hungary, Turkey, Japan, Egypt, Korea, and elsewhere, have all talked up the same “good times.” Television ratings and stock market indices have momentarily soared, in generally sluggish global economies, as have the global sales of weapons, sedatives, tranquilizers, and antidepressants.2

Anxieties about alertness, agency, hypnosis, and the nightmares of a catatonic seizure of the popular will by “fascism” often rear their head in the wake of sweeping victories for right-wing parties. Are we drifting into a disaster with our eyes shut, or sleepwalking with our eyes wide open?

For the past few decades, globally, many well-meaning but demoralized people, especially artists and intellectuals, but also activists, have been losing sleep. They suffer from a peculiarly debilitating activist insomnia consisting of relentless Facebook posting, forwarded petitions, and other rituals of narrowing particularity that have taken the place of heretical, insurrectionary, and transcendental visions. We are restless, exhausted through the operation of the worst, most damaging technique available to torturers: sleep deprivation. We could all do with a “sleep in” on the long night shifts. It appears as if there has been a generalized forgetting of the arts and sciences of dreaming, especially lucid dreaming.

This makes it sobering, and even mildly therapeutic, to undertake a close reading of a different account of sleep, and of awakening—the one that opens this essay, from Faridabad Workers News (FMS), a workers’ newspaper.

To recapitulate: One night in a factory, after a worker is admonished for his fatigue on the shop floor, 108 workers decide to fall asleep on the night shift. The gentlest possible refusal of capital’s rapacious claim on time and the human body. The newspaper goes on to say, “Workers in other sections of the factory followed suit. It became a tradition of sorts.”

We have been reading FMS—which is produced by some friends in Faridabad, a major industrial suburb of Delhi and one of the largest manufacturing hubs of Asia—for the past twenty-five years. The paper has a print run of twelve thousand, is distributed at regular intervals by workers, students, and itinerant fellow travellers at various traffic intersections, and is read on average by two hundred thousand workers all over the restless industrial hinterland of Delhi.

Over the years, this four-page, A1-size paper full of news and reports of what working people are doing and thinking in one of the biggest industrial concentrations of Asia has acted as a kind of reality check, especially against the echolalia—manic or melancholic, laudatory or lachrymose—that issues forth at regular intervals from the protagonists as well as the antagonists of the new order. In these circumstances, the paper acts as a kind of weather vane, a device which helps us scent the wind, sense undercurrents, and keep from losing our head either in the din of the ecstatic overture for capital and the state, or in the paralyzing grief over their attempts to strengthen their sway.

This month’s FMS, published a week before the results of India’s elections unleashed a frenzy of mourning and celebration, talks about questions coming to shore. It says,

While distributing the paper, we were stopped twice and advised: “Don’t distribute the paper here. Workers here are very happy. Are you trying to get factories closed?” That reading, writing, thinking, and exchange can lead to factory closures—where does this thought come from?

Perhaps this fear is a result of messages that circulate between the mobile phones of tailors. Or perhaps this fear emerges because workers on the assembly line are humming!The industrial belt that surrounds Delhi has been going through a deep churning over the last few years. Hundreds of thousands of young men and women are gathering enormous experience and thought at an early age. They are giving force to waves of innovative self-activity, finding new ways of speaking and thinking about life and work, creating new forms of relationships. In the gathering whirlwind of this milieu, many long-held assumptions have been swept away, and fresh, unfamiliar possibilities have been inaugurated. Here we are presenting some of the questions that have coursed through our conversations and which continue to murmur around us.

Why should anyone be a worker at all?

This question has gained such currency in these industrial areas that some readers may find it strange that it is being mentioned here at all. But still, we find it pertinent to underscore the rising perplexity at the demand that one should surrender one’s life to that which has no future. And again, why should one surrender one’s life to something that offers little dignity?If we put aside the fear, resentment, rage, and disappointment in the statement “What is to be gained through wage work after all?,” we can begin to see outlines of a different imagination of life. This different imagination of life knocks at our doors today, and we know that we have between us the capacity, capability, and intelligence to experiment with ways that can shape a diversity of ways of living.

Do the constantly emerging desires and multiple steps of self-activity not bring into question every existing partition and boundary?

In this sprawling industrial zone, at every work station, in each work break—whether it’s a tea break or a lunch break—conversations gather storm. Intervals are generative. They bring desires into the open, and become occasions to invent steps and actions. No one is any longer invested in agreements that claim that they might be able to bring forth a better future in three years, or maybe five. Instead, workers are assessing constantly, negotiating continually; examining the self, and examining the strength of the collective, ceaselessly. And with it, a wink and a smile: “Let’s see how a manager manages this!” The borders drawn up by agreements are breached, the game of concession wobbles, middlemen disaggregate.When we do—and can do—everything on our own, why then do we need the mediation of leaders?

“Whether or not to return to work after a break, and across how many factories should we act together—we decide these things on our own, between ourselves,” said a seamstress. Others concurred: “When we act like this, on our own, results are rapid, and our self-confidence grows,” and elaborated, “on the other hand, when a leader steps in, things fall apart; it’s disheartening. When we are capable of doing everything on our own, why should we go about seeking disappointment?”Are these acts that are relentlessly breaching inherited hierarchies not an announcement of the invention of new kinds of relationships?

In previous issues, we have discussed at length how the men and women workers of Baxter and Napino Auto & Electronics factories displaced the management’s occupation of the shop floor. During that entire time, workers did not leave the factory. Men and women stayed inside the factory day and night, side by side; this signals their confidence in their relationship. There are several instances too of temporary and permanent workers acting together to demand equal increments in wages and other facilities. People are acting against inherited divisions, forging uncharted bonds.Are these various actions that are being taken today breaking the stronghold of demand-based thinking?

The most remarkable and influential tendency that has emerged in this extensive industrial belt cannot be wrapped up, contained in, or explained via the language of conditions, demands, and concessions. Why? Over the years, the dominant trend has been to portray workers as “poor things,” which effectively traps them in a language that makes them seem victims of their condition and dependent on concessions. And then they are declared as being in thrall to the language of conditions, demands, and concessions. This is a vicious cycle. In the last few years, the workers of Maruti Suzuki (Manesar) have ripped through this encirclement.“What is it that workers want? What in the world do workers want?”

The company, the local government, the central government were clueless in 2011, they stayed clueless through 2012, and they are still clueless. This makes them nervous. That is why, when workers exploded despite the substantial concessions being offered by management, it resulted in six hundred paramilitary commandos being deputed to restore “normalcy.” A hundred and forty seven workers are political prisoners even today.

Do all these questions hold for everyone, everywhere in the world?

Do these questions hold for everyone, everywhere in the world?

A month before these questions were addressed to the worker-readers of Faridabad, the April 2014 issue of FMS featured a categorical statement, and another question. Both begin with the same declaration about what the paper thinks is happening to the seven billion people of our planet.

Today we can say with full confidence that an unsettling courses through seven billion people. It is inspired by the desire for an assertion of the overflowing of the surplus of life. It is an expression of creative, boundless astonishment.

Today we can say with full confidence that an unsettling courses through seven billion people. And relatedly, a crisis-laden astonishment: What happens to the colossal wealth that is being produced? Where does it go? How is it that such a tiny sliver from it reaches daily life?

Astonishment is an interesting emotion. It can signal a profound delight alloyed with surprise, as well as the kind of deep anger that borders on puzzled rage. In dreams, we are far more comfortable with astonishment than we are when we are awake and distracted. This double-edged astonishment features both a joy at the self-discovery of the multitude’s own capacities as a planetary force, as well as a recognition of how life itself is being drained of worth and value. This takes us to a new ground—a place of radical uncertainty. Here, both the perils and the potentials of a new global subjectivity lie in wait. Why can we not see them? Why can we not hear them call out? Perhaps they are feigning sleep, restoring themselves with an unauthorized midshift siesta that could break, if they wanted it to, any moment.

Perhaps, in places, it has already broken.

Emergence of factory rebels. Attack on factories by congregations of workers. Frightened management. Industrial areas turn into war zones. Rising numbers of workers as political prisoners. Courts that keep refusing bail. A mounting rebuttal on shop floors of the unsavory behavior of managers and supervisors. The dismantling of the managerial game of concessions. Irrelevance of middlemen. An acceleration of linkages and exchanges between workers.

“This,” says the paper, “is the general condition of today.”

The one thing that we can say with certainty is that management no longer knows what workers are thinking. They do not know what happens next.

Ebullitions all around, the unshackling of factories. Workers refuse to leave the factory. The undoing of the occupation of factories by management. Making factories unfettered spaces for collective gathering. Creating environments that invite the self, others, the entire world to be seen anew. Ceaseless conversation, deep sleep, thinking, the exchange of ideas. The joining together of everyone in extended relays of singing. The invention of new relationships. Whirling currents of possibility opened up by the making of collective claims on life.

This too is the general condition of today.

So how will the sinking ship of the state keep sailing? How will orders be given and obeyed if so few are even speaking the language of the captain anymore? For the ship not to sink, at least not yet, these orders must at least appear to be given and obeyed. Someone must semaphore.

Perhaps the rise of nationalism of the far right across the world is not as much a sign of the increasing power of capital and the state as it is a recognition, by those at the helm of affairs, of their own besieged situation. They are under siege. Once again the rulers do not know what is going on in the minds of those they rule. For all practical purposes, the subjects are opaque, oblivious to every command. Management does not even know whether the workers are asleep or awake. When they are asleep, they seem to be animated by the current of vivid dreams. When they are awake, they doze at the machine. Is this why every leader asks his nation to awaken? So that he can be reassured that they are at least listening to him? The more they sleep, the louder is the call to rise.

Postscript: The Kumbhakarna Proposition3

Kumbhakarna, a warrior in the Sanskrit epic Ramayana, is remembered for his ravenous appetite, enormous strength, ethical doubts (he did not want to fight in a needless war, but he did so when pressed, out of duty and loyalty), and his preference (given to him as a boon) for hibernating half the year away.

The Kumbhakarna Proposition is a proposal to recognize the revolutionary potential of the cultivated hibernation of a reticent strength, whose awakening has consequences. Like Kumbhakarna’s prowess, which some attribute to his preference for sleep over wakefulness, the radical move may derive its strength from gestation. To assert, propose, or desire seduction into a long period of invisible ferment may be seen as a wager to linger or loiter over thinking, as opposed to making haste for the purposes of execution. This is the time to dream lucidly. To envision and realize the things that one cannot do when one is awake, distracted, bored, busy. This is the time for hearing voices, to become open to the murmur of the universe, for heresy, for audacious conversations, for acts to turn factories into orchards, and a laughter that makes standing armies into brass bands.

Let them who rule risk fatigue with their watchfulness.

We wink to them, good night!

For occasional translations from lead essays, and PDFs of monthly issues, see →. All translations in this essay are by Shveta Sarda.

See text by Raqs Media Collective in The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating, ed. Jean-Paul Martinon (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).