1.

The idea of a society without qualities is an indictment of a state that fails to provide a life of quality for its citizens. The society without qualities is one in which a systemic pressure on cultural and democratic institutions results in a whittling down of civil liberties. Where post-fascism is on the rise and where those who revolt are regarded by the elite as expendable. Where human relations are corroded in profitable ways and the future of the youth is mortgaged. And so you are turned into your own limit: you are your own weakest link because it is up to you to hold things together. It is a society without the historical teleology that the twentieth century had as an “American century.”1

Of course, the society without qualities is a consequence of the evacuation that has taken place. Having realized itself to the extent that it has shed its historical constraints, capitalism is now free—victorious when identified with the state, when it is the state (Fernand Braudel).2 And so the idea of the state as a caretaker and an educator, an alleviator of pain, is no longer believable. The state has been presented with a new role, which it has accepted. Capitalism’s convergence with the state dissolves society—this was what Margaret Thatcher spoke of with the honesty of an executioner.

The rise of the society without qualities comes as a bigger surprise on the European side of the Atlantic. The European welfare state has been dismantled by a right wing that incredulously considers it to be a vestige of socialism, and by ideologically homeless social democrats ready to liquidate what was once commonly owned.

The welfare state is a model of economic redistribution that is frequently mistaken for a social community—perhaps because of the mental (libidinal?) economy that it also is: a psychic investment in, or occupation of, other people through the state apparatus. Because the welfare state maintains infrastructure, education, health care, and so forth, it is believed to guarantee tolerance, trust, and empathy. But we must strip the state of its sham human qualities. After all, if modern man and woman are anyhow without qualities, why should the state possess them?

Contemporary welfare revolves around capitalism and the nation. The success of the right during that last twenty years comes down to its—at this junction technically correct—identification of welfare with these two parameters. What remains is too often a nation-state that continues to dream of its interiority and abjures the social and economic margins of the world—effectively, the nation-state as cordon sanitaire. Since 1989, it has often been said that we live in a world with no outside. But don’t innumerable social margins count as outsides?

2.

According to nineteenth-century pioneering Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt, the modern political spirit of Europe was in Renaissance Italy embodied by the state as a work of art.3 The omnipotent state is a “purely modern fiction” in which war is “a democratic pursuit” and the people become reduced to a disciplined multitude of subjects.4 If the intelligence, artistic talent, and intolerance of the amoral Renaissance man seemed an exotic contrast to Burckhardt’s dull nineteenth century, the Renaissance man has returned in the guise of today’s art-loving oligarch.5 Considering that to Burckhardt, despotism represents the beginning of the modern state, his text can be compared to Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the Enlightenment as the double-face of what is at the same time progressive and totalitarian modern reason. Preferring to convey an impression of a bottomless abyss rather than any notion of moral progress in history, Burckhardt brought the news of “the absence of all guarantee for the future.”6 The society without qualities.

3.

Even as it is voided of significance, “welfare” and social security continue to be a strong referent in politics. The nostalgia belies the fact that no return to what welfare once meant seems possible. The modern state has converted qualities into functions and economic relations. To provide economic protection for citizens is a fundamental function in a world dominated by money and property. But economic protection and the absence of exploitation are two different things. The commonality now offered by the welfare state can simply be interpreted as a foundation for competition.

From the point of view of sociology—usually prudently self-restrained in its acceptance of what exists—the society without qualities is the network society: a social order that is integrated into global networks of instrumentality through new information technologies. However, if the idea of a society without qualities has the potential for becoming, this is ultimately located beyond sociological description. The society without qualities can never become manifest, because it is a place in the future where something that is different survives. Like every active thought, the impossibility of its full legitimation is branded on it. As Adorno said, the true society will leave possibilities unused.7

The society without qualities is not a narrative of loss. It is evoked through an interest in description as much as in critique. Description—not as an adequate account, but as a way of exhausting or expending an object that has been revealed.8

4.

But the society without qualities can also be embraced as the precondition for a society to come. “The society without qualities is something we are all waiting for” (Ulrika Flink).9 Waiting … without fascination or anxiety. Across the twentieth century, from one-dimensional wo/man to the public intellectual and the enragés, Ulrich—Robert Musil’s indifferent Viennese protagonist in The Man Without Qualities (1930–1942)—confronts us from another waning empire. References to Musil’s novel reappear in epochal texts, such as Hardt and Negri’s Empire (2000), where it is quoted to describe the shift of modernization towards the expropriation of the common and the dissolution of the concept of the public. However, in a society without qualities, it is society rather than the human being that is deliberately left blank—stripped of the One, of originary myth and normative expectation. The One is neither the premise nor the promise of the multitude. Why would the many need a form of unity anyhow? And one would like this erasure to become something other than die Vereinigung von Seele und Wirtschaft—the union of soul and economy.10 Let us gaze fearlessly at the modern city that is born in capital.11

“The nation States see their traditional role of mediation being reduced more and more,”12 Félix Guattari wrote in the late 1980s. The difference between then and now is that today it is all out in the open. When no longer interested in redefining citizenship in the positive, nation-states become mediators in the purely logistical and expedient sense of the word. Mediation is an end in itself in a logistical world where meaning is mobile. Jaime Stapleton writes about the metaphors of surface and horizontal relationality that dominate both political neoliberalism and post-structuralist approaches to meaning: “A Society Without Qualities is a society in which no given part has any interior quality or determination of its own, but whose character is determined quantitatively in relation to all other parts, that are each determined by their relation to each other and the given part.”13

5.

“Art did not die. But it became a reality machine” (Søren Andreasen).14 Today art is a norm—knowable, possible, prescriptive. No longer an outsider or pariah, the artist is now identified as an exemplary agent, a problem crusher, the embodiment of the self-consuming subject. By now this is yesterday’s news, and hence it is an insight that cannot be universalized, since artists today have developed counter-strategies.

Money is the one thing that connects us and that we cannot truly have in common. In societies without qualities we can, in theory, have any number of things in common. However, after the decline of symbolic orders, it is an enormous effort to call them up and give them words and form. Remember, this is the desert of the real … So never mind good intentions, they won’t get us anywhere: when art addresses the future in (self-)skeptical ways, it refuses nostalgia and hope as sentimental compensations for an uncertain future. There is an indignity in speaking on behalf of others (Gayatri Spivak), but it is equally irrelevant to direct and instrumentalize your symbolic acts, because they are like children: there is no knowing what they will get up to. They wander off on their own and should be allowed their freedom. The aesthetic experience is an overlooked precondition for comprehending social conflict. Perhaps one can incorporate disillusionment into a politics of undoing that urges us to hear the unheard-of with our own ears, to touch the un-apprehended with our own hands.

Gilles Deleuze once remarked that to be a leftist means to orient oneself towards the future, to think a little further ahead. This future orientation is in a general sense also where the leftist political project intersects with art, because art is that which is not yet identified by culture at large, not yet known or purposeful. This doesn’t mean that art is inherently leftist, or somehow immune to becoming a thing or a product, only that the Left lets its own project down when it forgets that it is aligned with art in the struggle against capital’s colonization of the future.

6.

Aesthetic problems can’t be solved in the social sphere, and vice versa, because the two are one, and the one becomes two. The social begins and ends in art, but not the other way around: art dies when it becomes a model. In art, the social limit of freedom can be perceived.

Are models necessary? Social models usually have a mimetic relation to a given reality, and they start with the whole, not the part. What if we check our desire to project figurative qualities onto the future and desist from producing models that may improve society as it exists? What would it mean to engage in historical processes and social struggles, but proceed without a specific model or image of the society to come? How can we take a cubistic approach, dispensing with the falseness of the whole?

Arguably, such an approach can only be articulated momentarily, as a flash, and maybe its sense of undoing and letting go relates first and foremost to aesthetic experience. In the early 1970s, Jean Baudrillard gave an alternative, downbeat definition of utopia: utopia, he wrote, is what is never spoken, never on the agenda, but “always repressed in the identity of political, historical, logical, dialectical orders.”15 Utopia is what the order of the day is missing … Something elusive that dies when aggressive interpretation sets in. When utopia is deprived of its telos, it becomes compatible with aesthetic thinking, with the ambivalence and skepticism through which art returns real events and bodies to virtual non-places. Like utopia, art is insoluble and uninhabitable, its speech threatened by reality principles.

7.

Admittedly, the society without qualities sounds like a famous song by John Lennon about imagining no countries, no money, and no religion too … But unlike Lennon’s utopia, in a society without qualities there will still be something to die for. There is no more beach underneath the cobblestones. The vision of a center-less, image-less society could not come from the ’60s. However, the credos of 1968 abide, often because we imagine that we, from our winter of capital, have direct access to the Summer of Love and the ethos of May ’68. But for all their fighting spirit and their capacity for multiplying political struggles, what makes the soixante-huitards unacceptable today is their gender blindness and heteronormativity, their populist eagerness to square off with the spectacle, their Romantic ideas of a radical subjectivity, their inability to articulate their disaffection in something other than affirmative terms, their exaltation of desire, their nationalism, and their awful music.

Why not accept that drama has left politics? This doesn’t mean that there is nothing to discuss, or that history has ended, or that suffering has ended. Far from it. Today we are hungry for historical drama because it used to signify change, and if May ’68 affirmed something it was that affect and historical change belong together. But with their photogenic insurrections, the ’60s created a dramaturgy that speculated on the separation of drama and change, thereby making it possible to instrumentalize affect and turn change into a simulacrum. There is no causal relation between drama and change.

8.

Rote Armee Fraktion, Sendero Luminoso, Brigate Rosse, The Weather Underground, Blekingegadebanden, and so on. Direct action founded on a paranoid logic, whereby armed struggle was turned into the ultimate fetish of the political project. The notion of “political terrorism” is probably a contradiction in terms, if by politics one means that which concerns everybody in the city, whereas terrorism always concerns only a chosen few.

The death of the terrorist was the stake on which the system, through its own violence, impaled itself. This is how Ulrike Meinhof became an icon. The discussion of whether she committed suicide or was in fact murdered in her prison cell is beside the point. What matters is that she invited the system to destroy her, thus making it impossible for it to do away with her. A sacrificial death, because in sacrifice, one destroys an object—but not completely. There is always a remainder.

Terrorism today is religious fundamentalism, individual loose cannons—and state terror, of course, the one we tend to forget. The conditioned response of the authorities—“We don’t negotiate with terrorists”—is now redundant because terrorists no longer make demands. Once they took hostages to negotiate; today they mow down people without articulating a challenge to the system. And so terrorism creates an alibi for the state’s atrophied functions according to which disruption is internal to systems of circular control and usually results in heroic law enforcement, increased security measures, and another four years for the president. This can’t hide the lamentable fact that Al-Qaeda represents the only alternative to late capitalism.

The difference between late-twentieth-century and contemporary terrorism reflects the shift from a dialectical understanding of history to a cybernetic one. History now plays out inside networks. And so terror is no longer an antithesis to the system but an occurrence inside it. When Al-Qaeda, struck the US in 2001, they targeted material switches (Wall Street; the Pentagon; Washington, DC), thereby temporarily disrupting the flows of people, money, air traffic—in essence, governance.

Ironically, the question terrorism can’t answer is how to bring back death in a society that denies death as it celebrates the ephemeral, makes death meaningless by its repeated representation in the media, “always as the other’s death so that our own is met with the surprise of the unexpected” (Castells).16 Perhaps this is why hostages are no longer taken: people count for network flow, and killing people is a symptomatically distracted way of targeting the sublime target, the internet. It is obvious that when terrorism begins to revolve around questions of system maintenance, it no longer represents an embarrassment to the system itself.

9.

Two prevalent representational modes in culture today are the shop and the parliament: the department store with a selection of leading brands, and the democratic forum empowered to act on behalf of the citizenry.

Many exhibitions, especially biennials, are organized like the marketplace or the parliament: inclusive, anthologizing, consensus-driven, reproductive, covering bases in terms of expression, media, geographies, and politics. Promising adequacy or completeness, however, will only reflect what already exists. So why do curators so often assume a representational brief instead of seeking to exacerbate difference? Representational models are spatial; they address and reflect the notion of contemporary art as a field or an “art world,” and so they do little to change the way that time is eclipsed in a connected world. Breaking the mimetic mold of the curated space may help stimulate the temporal dimension of exhibition-making, and thus augment sensibilities towards change.

10.

Direct responses to capital are difficult because capital is a shape-shifter and a parasite that already banks on a response—any response. However, this also implies that its intelligence is predictable. There is a thickness to capitalism. Its lack of love is obtuse. It picks up speed when there is an infrastructure in place for it to work, when everything is ready for it to take over. These conduits exist in the social world, but capital also relies on its mental progress in our brains and nervous systems. At the same time, the credit system turns time into an infrastructure for money. Therefore, our nervous systems, imaginations, and subjective and social time are as good a place as any to start: instead of going head to head with capital, we might learn from its subtractive protocols and become as corrosive as money.

11.

Have our imaginations become so poor that we cannot think society without these two incredibly boring matrices, state and capital? It would be pathetic if we couldn’t come up with something better.

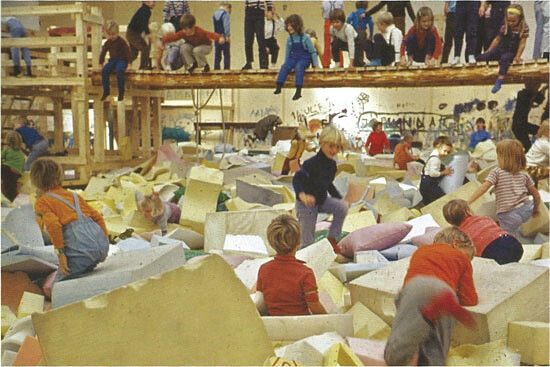

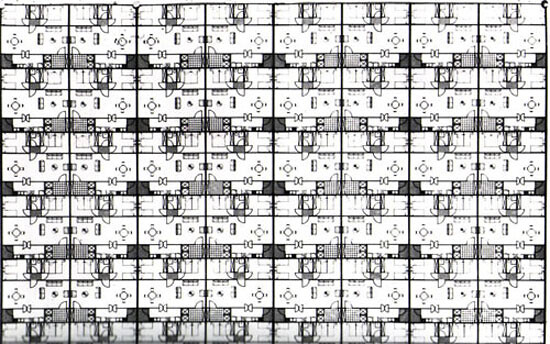

“The Society Without Qualities” (or in Swedish, “Samhället utan egenskaper”) was the title of a group show that took place at Tensta Konsthall in Stockholm, February 14–May 26, 2013, in the framework of the research project The New Model: An Inquiry, which Maria Lind and I initiated. The exhibition included works by Ann Charlotte and Sture Johannesson, Joanna Lombard, Jakob Jakobsen and Anders Remmer, Sharon Lockhart, Palle Nielsen, Archizoom Associati, Jakob Kolding, Xabier Salaberria, Ane Hjort Guttu, Learning Site with Jaime Stapleton, Søren Andreasen, Thomas Bayrle, and Dave Hullfish Bailey. I curated the exhibition.

Fernand Braudel, Afterthoughts on Material Civilization and Capitalism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), 64.

Jacob Burckhardt, The State as a Work of Art (London: Penguin, 2010 (1860), 2.

Ibid., 8, 87, and 95.

Cf. Ritchie Robertson’s essay “Burckhardt’s Renaissance, 150 years later.”

Burckhardt, The State as a Work of Art, 40.

T. W. Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life (London: Verso, 2005 (1951)), 156.

Georges Perec, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, trans. Marc Lowenthal (Cambridge, MA: Wakefield Press, 2010 (1974)).

In an email to the author on October 11, 2012. Ulrika Flink is Assistant Curator at Tensta Konsthall.

Robert Musil, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2013 (1930–1942)), 107.

See Andrea Branzi on Archizoom Associati, quoted in Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture within and Against Capitalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), 75.

Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (London: The Athlone Press, 2000 (1989)), 29.

From Jaime Stapleton’s text “The Monologue,” part of Learning Site’s sound piece Audible Dwelling 0.2 (2013).

In a telephone conversation with the author, May 21, 2013.

Baudrillard, “Utopia Deferred” (1969), in Baudrillard, Utopia Deferred: Writings for Utopie (1967– 1978), trans. Stuart Kendall (New York: Semiotext(e), 2006), 62.

Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 484.