Like others among the twenty or so people witness to Sharon Hayes’s Everything Else Has Failed! Don’t You Think it’s Time for Love? (2007), I spent each lunch break during the week of September 17th, 2007, crying at the intersection of West 51st Street and 6th Avenue in midtown Manhattan. The performance consisted of Hayes walking out of the United Bank of Switzerland (UBS) building shortly after noon carrying a small speaker and a microphone on a stand, and reciting a love letter from an anonymous speaker to an absent “you.”1 The letters gradually established a loose narrative in which the speaker has been separated from her lover by circumstances related to the war in Iraq.2 The two had been able to maintain something of a relationship via letters, but the speaker has stopped receiving replies from the lover and, as such, has resorted to speaking the letters in public in the hopes that this gesture will inspire a response.3

Surely my tears flowed because of this longing, this gesture of love rendered unrequitable by ostensibly unassailable, intertwined institutions that keep the lovers apart: the military-industrial complex, states and citizenship, and homophobia. Hayes’s skill at delivery—her ability to use her voice to convey the yearning and the loss contained within the letters—certainly contributed to this intensely emotional response from her audience. The passion and conviction with which she infused her voice stood in stark contrast to the besuited bankers scurrying about during their lunch hour talking on their cell phones. She tried to make eye contact as unsuspecting people walked in front of her, in the space between her speaking body and the audience gathered to listen to that day’s oratory. Occasionally, someone would stop, but more often than not, if they even noticed her, they would quickly look away and hurry along out of eye—and earshot.

This clear disjunction between the audience and the general public served a purpose within the performance, alluding to how love functioned as the basis of Hayes’s antiwar statement. The dynamic present between those who understood and were interested in the performance, and those who didn’t and weren’t, productively reproduced the structure of subcultures, illustrating the gulf between those who live comfortably within the values and hierarchies of dominant culture and those who use those structures against the mainstream.4 As such, Hayes highlighted that her use of love was drawn from a subcultural context, raising the question of what love means within that setting.5

Everything Else Has Failed… points towards specific instances in which subcultures have mobilized love to political effect. The most prominent reference is to the American hippie counterculture of the late 1960s, which looked to love as a way to construct an alternative social order while simultaneously protesting the war in Vietnam with such slogans as “Make Love not War.” For hippies, dropping out of society and forming alternative economic and kinship structures with different standards and ethics—all through the language of love—was an intensely political act. Not surprisingly, Hayes has pinpointed the origins of this performance’s title in an archival image from Berkeley in the late 1960s, which depicts a man sitting in the middle of a protest holding up a sign that reads: “Everything Else has Failed! Don’t You Think It’s Time for Love?”6 The sentiment conveyed by the sign, and by Hayes some forty years later, is that love encompasses an alternative understanding of political activity in the face of governmental processes that, then as now, are either unable or unwilling to address grave social and economic injustice.

What this alternative, subcultural, and queer form of politics is—its shape, scope, temporality, and purpose—receives systematic exploration in the intermedia practice of the Canadian artist group General Idea, active from 1969 to 1994. The example set by General Idea offers some answers to the questions raised by how Hayes positions her use of love, based on how the group engaged with the politics of everyday subcultural life throughout its career. General Idea’s work helps us see how Hayes and other queer and feminist artists in her milieu use their art practices to explore not just alternative methods of politics, but an entirely different model of what constitutes politics altogether. The goals of this politics are not to institute different public policies or forms of government that are more equitable. It is, rather, about creating spaces, systems, and structures in the present moment for subcultural participants to have some form of agency: to determine their own morals, values, and hierarchies; to establish their own terms of identification and subjectivization; and to briefly exist without being subject to immediate policing by dominant culture. A contingent subaltern version of performative biopower, as opposed to a movement to completely overhaul society.7

Consisting of the trio AA Bronson, Felix Partx, and Jorge Zontal, General Idea’s entire practice highlighted the political operation of subcultural social life, of the everyday activity of subcultural participation, in contrast to elections or demonstrations.8 In a 1997 catalog essay, Bronson expressed the group’s motivation in terms that uncannily echo the statement on the Berkeley protester’s sign, though for General Idea even the hippies represented a form of orthodoxy:

We had abandoned our hippie backgrounds of heterosexual idealism, abandoned any shred of belief that we could change the world by activism, by demonstration, by any of the methods we had tried in the 1960s—they had all failed … We abandoned bona fide cultural terrorism and replaced it with viral methods.9

General Idea disidentified with the bona fide earnestness of the hippies’ methods, not so much because those methods had failed to change the world, but because of the counterculture’s aspirations to change the world in the first place. Rather than try to instrumentalize social life to overthrow dominant culture, to repeal sodomy laws or end wars, the subcultural politics that General Idea highlighted created alternative social orders in the present, using the systems and structures of dominant culture against itself to allow different possibilities for identification and subjectivization.

From the outset, General Idea incorporated its subcultural social milieu into its performances, videos, installations, and even its magazine, FILE, published from 1972 to 1989. The group demonstrated an exceptional commitment to both underscoring and also modeling the ways that subcultures function politically. Its work emphasized the role that alternative ideas about sexuality played within those subcultures. Sexuality was about more than just sex and desire, however—it stood in for a form of critically engaged embodiment, including the entire matrix of identification and subjectivization that frequently constituted the primary site of intervention for these subcultures, be they the group’s correspondence art network or its local gay bar scene (though it is no coincidence that many of these sites overlapped). As Bronson described it, “The whole thing about sexual freedom was a big topic, and the lack of definition around sex was more important than identity really. It was very free-form, and there was this idea that sex could move in any direction at any time.”10 Denizens of these subcultures used the forms and structures of identity available within dominant culture, but redeployed them in a manner that refused many of the assumptions that undergirded mainstream ideas about identity, including its fixity and its essentialism. The prominence of taking on assumed names and characters within General Idea’s network—as the group did twice over, not only with their individual names but also with their collective identity—is an obvious example of this tendency. Sexuality was a primary site that the group chose to present in its exploration of the political operation of subcultures, presenting the body, not the public sphere, as the site of intervention.

One of the group’s first large-scale projects exemplified its commitment to performing subcultural politics. The Miss General Idea Pageant provided a framework for General Idea from its first iteration in 1970 through its last performance in 1978. The performance materialized differently with each staging, as a fully scripted event in 1970 and an actual competition in 1971.11 Subsequent pageant performances, from 1974 to 1978, restaged aspects of the 1971 event to rehearse audience reaction for the next competition, set to occur in 1984.12 The grandest of these rehearsals was Going Thru the Motions, which took place at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in 1975. The event was a large-scale affair, with elaborate staging, many parts, and multiple musical interludes by the popular Toronto-based band Rough Trade.13 What was noteworthy about the event, as it applies to General Idea’s relationship to its subcultures, was how it blended scripted and unscripted elements. The group conceptualized Going Thru the Motions as a performance for video, and the cameras rolled from the first guest’s arrival through the last’s exit, capturing the intermission with as much detail and care as the staged and scripted elements. The audience played as much of a role in the work as the figures on stage, perhaps even more so, as the entire event revolved around rehearsing the audience’s reactions to prepare for the event to come in 1984.

The importance of subcultural social life, and specifically socializing, to Going Thru the Motions, and to General Idea’s practice in general, becomes clear over the course of the intermission. The group included a bar, the Colour Bar Lounge, as part of the setting for the performance. It was a fully stocked cash bar, though it quickly sold out of alcohol and had to be resupplied part way through the event. General Idea specifically constructed and filmed the activity at the Colour Bar Lounge, and included interviews with members of the audience that reference it. These interviews discuss various drinks on offer at the bar, like the Golden Shower, that specify these as sexual subcultures. By highlighting this space of drinking and of cruising, the group not only references a history of artist bar hangouts, such as the Cedar Tavern for the Abstract Expressionists or Max’s Kansas City for the Minimalists and Warhol’s entourage, but also turns viewers’ attention to the subcultural orientation of the entire pageant performance. General Idea incorporated prominent members of its subcultures into its performances, and used subcultural spaces as part of the staging of the Pageant.

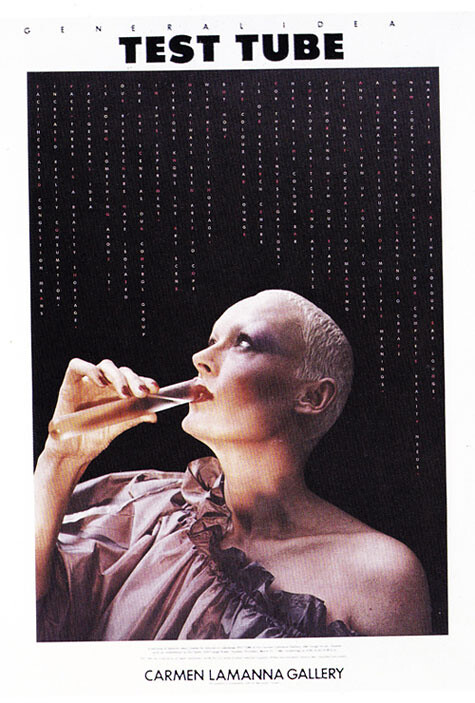

While General Idea emphasizes the fact that it incorporated its subcultures within Going Thru the Motions, it explains the political operation of those subcultures in a later work that also takes place at the Colour Bar Lounge: the 1979 video Test Tube. The video unfolds like a television program, another form which General Idea occupied and rearticulated for subcultural purposes.14 Test Tube takes the form of a soap opera, but through the story of the episode it also clarifies General Idea’s subcultural politics.15 The video unfolds over five sections, each of which presents a different political ideology in three parts: General Idea in the Colour Bar Lounge establishing the ideology of the given section, an artist and new mother considering that ideology in relation to different frameworks for artistic practice, and then a drink for sale at the bar—a metaphor for the ideology. These settings—a bar, a domestic household, and advertising—link the consideration of politics to the spaces and activities of everyday life.

In the scenes from Test Tube where General Idea speaks, the group combines the language of research and development with that of intoxication, playing on the ability of capitalism and dominant culture to intoxicate subjects and distort their perception such that they no longer recognize how either shapes their lives. At the same time, General Idea uses the video to demonstrate how systems and institutions of dominant culture offer the possibility for inhabitation and redeployment for subcultural purposes. Later in the video, Jorge Zontal explains, “We don’t want to destroy television. We want to add to it. We want to stretch it until it starts to lose shape, stretch that social fabric! Just imagine all those new sensibilities taking up more and more room, all those chaotic situations on the fringe of society flooding into the mainstream.”16 This statement encapsulates the group’s presentation of subcultural politics, of occupying and rearticulating dominant culture to create space for alternative social orders and modes of identification. This was its viral method, set against hippie heterosexual idealism, performed on a daily basis through subcultural social life.

I began work on a dissertation on General Idea shortly after first moving to New York, and it presciently provided me with a framework and a vocabulary to understand what I viscerally felt to be so pressing and vital in work like Hayes’s performance. While General Idea presents an alternative and expanded notion of sexuality as part of its subcultural politics, though, it falls upon contemporary queer and feminist artists to expand upon General Idea’s observations within a specifically and self-consciously queer social life and community. Describing why she was drawn to the protest photograph from which the performance draws its title, Hayes notes that it pointed to the social act of love—outside of a romantic context in its declarations to an indeterminate “you”—as itself political.17 Hayes does not explicitly define the love that she references and performs within Everything Else Has Failed... When discussing the project, however, she often refers to the work of another artist, Emily Roysdon, who explicates love as a politicized aspect of everyday queer life. Roysdon, whose work engages photography, choreography, and curatorial practice, specifies love as “a strategy, medium, site, and scene.”18 She clarifies, “I must be explicit—Queer Love. Queer love exemplifies itself by its lack of singular object relations and an insistence on unstable and mutable boundaries.”19 And her notion of love is inextricable from queer subcultural life: “The theater of queer love employs politics, poetics, and aesthetics in equal measure.”20 This love, for Roysdon, denies the very structures of dominant culture in part because of its refusal to differentiate among art, politics, and the social realm.

For both Roysdon and Hayes, love is a lived critical engagement with and disarticulation of dominant culture. Hayes models this through her composition of the letters, drawn from historical love letters, speeches, protest songs, and slogans—from Bob Dylan lyrics to ACT UP slogans to lines from the resignation speech of New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey, delivered in 2004 after being caught in a homosexual extramarital affair. Re-speaking has long been a part of Hayes’s work. But Everything Else Has Failed… presents this form of appropriation and rearticulation—of occupying utterances from other times and contexts and using them for one’s own purposes—as part and parcel of Roysdon’s understanding of love, and thus intimately constitutive of queer life.

Two queer and feminist art collectives, one of which has Roysdon as a member, invert the emphasis in Everything Else Has Failed…, more concretely presenting queer social life while more obliquely engaging with traditional ideas of politics. These two groups, LTTR and Ridykeulous, both have wide-ranging practices that include intense collaboration, both in the groups’ own work and also in the art of others that they incorporated into their own.21 Much like General Idea, both groups have organized shows, printed matter, and events that double as social occasions. As such, like General Idea, these collectives use their artistic production to highlight the political operation of queer subcultures, in the process rearticulating the temporality and ontology of politics.

LTTR, an artist collective founded in 2001 by Ginger Brooks Takahashi, K8 Hardy, and Emily Roysdon, with Ulrike Müller joining in 2005, describes itself as “a feminist genderqueer artist collective with a flexible project oriented practice,” including “an annual independent art journal, performance series, events, screenings and collaborations.”22 LTTR works from its social and artistic cohort, creating performances, events, and printed matter that provide its peers space to interact with each other and to present their own work as part of a larger conversation about the politics of social life. Their art events are intentionally indistinguishable from social events, and programmed conversations take on an added urgency and relevance because of a radical equality among all participants, be they tenured professors or artists without gallery representation. Much contemporary art has engaged with the idea of the social, and of social practice, where the latter term refers to art practices that serve a specific social function, like founding a non-accredited art school, a la The Bruce High Quality Foundation University (2009–), or establishing an office to serve as the headquarters for an immigrant rights movement, as Tania Bruguera did with Immigrant Movement International (2010–2015).23 LTTR has certainly participated in this discourse about participation and social practice art, but at the same time, the group has rejected much of this discourse’s universalist framing in the interest of a specifically subcultural address. While other participatory practices have tried to demonstrate that the art object is always embedded in a world defined by social relations, LTTR makes already existing social practices the stuff of art.

While LTTR creates opportunities for its social circles and their practices to materialize, another queer and feminist art collective, Ridykeulous, produces publications and events that more explicitly formalize the extent to which the network it belongs to views making art as inextricable from making a subcultural community. Founded in 2005 by artists A.L. Steiner and Nicole Eisenmann, the project has materialized in the form of exhibitions and a zine, but also as more loosely structured events and even angry letters to artists, art publications, and the New York Times. Steiner and Eisenmann have described Ridykeulous as an amorphous, collective enterprise that is itself a social transaction.24 The group is deliberately undefined, with projects materializing through conversations with friends and not just between its two primary artists.

In a 2009 interview, Eisemann elaborated on the group and its relationship to social interactions, clarifying how its collectivity is an extension of its social and artistic subculture:

I think collectivity is really … sometimes it’s about using other people’s skills or other people’s ideas but its also about understanding what a community is. Collectivity has lost its form in the art world because it seems to be about making products but I don’t think that anyone working collectively, either singularly or collectively (or singularly and collectively like we are because we’re doing both), I don’t think anyone is doing it because they want to make stuff. They also want to do it because of the social interactions and then the social interactions, of course, enumerate when you call together a group. Say I am doing this project and people show up—then they’re automatically a part of the collective. It’s not like they are an audience. We are really hostile to the idea that people come as audience members because I think that’s really passive.25

Ridykeulous posits an even more intimate relationship between the various forms of labor that constitute artistic practice and the labor of supporting a subculture, since its work is inexorably both. Because its work is even more socially oriented, and because the work of the colleagues who it includes is often so resolutely indicative of the collaborative milieu that supports so many artists, Ridykeulous enables a social and artistic subculture that uncannily echoes General Idea.

Putting General Idea in conversation with Sharon Hayes, LTTR, and Ridykeulous demonstrates the continued urgency of General Idea’s presentation of subcultural politics as not just an alternative avenue to achieve social change, but as an entirely different conception of politics. The two moments seem to share not only disillusionment with traditional structures of politics, but also a different temporal address. Subcultural politics and queer politics both work in the present, making space for alternative social orders and modes of subjectivization now, rather than trying to affect change in the future. The street is not dead, and public policy certainly matters, but not all subjects have access to the street, and public policy seems increasingly unable to adequately address the matrix of factors that impact inequality in our contemporary moment. We cannot regulate our own banks, let alone flows of global capital based on alienation and exploitation. Once again—as the Berkeley youth did, and General Idea did, according to Bronson—we face a failure of traditional politics. As such, Hayes, LTTR, and Ridykeulous, not to mention many of the other artists who constitute their cohort, offer a politics of the present, highlighting how their queer subcultures create alternative social and economic orders now, however ephemeral they may be, while also working towards more traditionally recognizable forms of social justice.26

Ultimately, what General Idea observed, and what seemed to motivate the urgency I felt participating in the scene that included Ridykeulous and LTTR, was a reformulation of what constitutes politics, and a reevaluation of the stakes of the social field and social life in light of this reformulation. By linking artistic and cultural practice, the artists under discussion here highlight the power of each to act on its own, without needing to be instrumentalized within a larger project of social change. Each artist or group highlights social activity as an agent that has the power to analyze, explicate, and impact culture at large. This potential is not limited to subcultures, subcultural practices, and subcultural objects. Rather, as General Idea and the other artists I have addressed demonstrate, it is within these sites that this potential is self-consciously explored and productively exploited. By formalizing social life within their work, these artists model the generative nature of social life, of the present, and of the ephemeral. This model carries as much pertinence now as it did forty years ago for communities disenfranchised by official institutions of culture and government, communities that need a way to formulate and make sense of themselves and their lives outside of mainstream structures.

The performance occurred as part of the show 25 Years Later: Welcome to Art in General, installed at the UBS art gallery on the occasion of the non-profit arts organization Art in General’s twenty-fifth anniversary. Rather than a retrospective of the organization’s work, the show was conceived of as a series of creatively staged encounters between art and the public. For more on the exhibition, see →.

Although the details of the story are ambiguous, over the course of the performances it becomes clear that for a time the lovers lived together in New York, until the absent lover’s family demanded that she leave the country, having something to do with the war in Iraq. Hayes’s speaker offered to accompany the absent lover, but the offer was refused. Thus began the epistolary exchange that provides the context for the performance.

Documentation of the entire piece, including audio, is available at the artist’s website here →.

The model of subcultures that I use throughout this essay draws from the work done at the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, particularly as enumerated by Stuart Hall and Dick Hebidge. Both scholars looked at the everyday activity that constituted participation in a variety of subcultures, from soccer hooligans to punks, and discussed how that activity constituted an active political engagement with creating space for alternative structures and values. Two aspects of their discussion of subcultures are particularly pertinent to this essay. The first is the fact that everyday social activity can constitute active political engagement, and the second is the prominence of détournement within subcultures, wherein subjects take a process or object from dominant culture and use it for a different purpose. Both of these scholars render everyday activity political—political because of the work it does in the present moment, rather than trying to affect change in the future. The artists discussed here likewise endow everyday life with political agency. See Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain, eds. Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson (New York: Routledge, 2000); and Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (New York: Routledge, 2004).

For more on the role that subcultures play within this work, see Virginia Solomon, “Politics of Queer Sociality: Music as Material Metaphor,” exhibition catalog, Farewell to Post-Colonialism: The Third Guangzhou Triennial (Guangzhou: Guangdong Museum of Art, 2008), 314–317.

Julie Carson, “Now, then and love: Questions of Agency in Contemporary Practice, Interview with Andrea Geyer, Ken Gonzales-Day, Sharon Hayes, Adrià Julià, Juan Maidagan, Emily Roydson (LTTR), Stephanie Taylor, Bruce Yonemoto and Dolores Zinny,” Exile of the Imaginary: Politics, Aesthetics, Love (Vienna: Generali Foundation, 2007), 163.

In the first volume of his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault describes biopower as a method through which the modern, capitalist nation-state controls populations by disciplining bodies via productive, and not just repressive, processes. This carries the consequence that norms and discourse create the possibilities and limits for bodies, in addition to explicit forms of regulation that allow and prohibit behavior. In the case of subcultures, power flows in the opposite direction, in the sense that subcultures provide a space to rearticulate norms and discourse, and for the bodies of the participants to enact that rearticulation.

Bronson, Partz, and Zontal were pseudonyms for Michael Tims, Ron Gabe, and Slobodan Siai-Levy, respectively.

AA Bronson, “Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea’s Bookshelf, 1967–1975,” The Search for the Spirit: General Idea 1968–1975, ed. Fern Bayer (Toronto: Art Galley of Ontario, 1998), 18.

Interview with the author, March 10, 2008.

Any consideration of General Idea, particularly of its work through 1975, owes an impossible debt of gratitude to Fern Bayer, the group’s archivist, who helped organize the most thorough consideration of the group’s early work for the exhibition The Search for the Spirit: General Idea 1968-1975, and its attendant catalog. For more, see The Search for the Spirit, ibid.

The competition at the 1971 pageant occurred based on photographs submitted by friends of General Idea, who followed criteria that the group outlined in the submissions packet sent to each participant. Vancouver-based artist Marcel Dot (Michael Morris) was crowned Miss General Idea 1971–1984 for his photo, which “best captured glamour without falling into it,” parodying glamour without enacting it as a part of his persona. General Idea crowned Dot Miss General Idea 1971–1984 for a number of reasons. The date—because of its Orwellian connotations and its association with a general notion of the future—was evocative of the correspondence network of which General Idea was a part. Many of General Idea’s cohort also made work throughout the early 1970s that incorporated 1984, including Glenn Lewis’s The Great Wall of 1984, which consisted of a wall of cubby holes, each of which was filled with an object submitted by another member of this correspondence network. The Great Wall of 1984 was installed at the National Library of Canada in Ottawa. From a purely logistical standpoint, though, General Idea also granted Dot a thirteen-year rein because the group could not fathom organizing another competition in 1972, and because the year 1984, due to its connotations, seemed as good an end date as any.

Rough Trade was a new-wave band founded by Carole Pope and Kevin Staples in 1968, though it did not perform as Rough Trade until 1974. The band achieved relative success, due in part to its frank embrace of raw sexuality, with out lesbian Carole Pope frequently performing in bondage attire.

The work was commissioned by De Apel in Amsterdam as a part of the gallery’s series of artist videos made for Dutch TV. Steeped in Marshal McLuhan’s ideas about the power of technology, and witness to the ways in which TV disseminated American culture as a form of unmarked, universal global culture, the work nonetheless also continued General Idea’s exploration of the possibilities of subcultural politics.

The video tells the story of Marianne, an abstract painter struggling to juggle the conflicting demands of the market, a desire for critical cultural relevance, and a new baby.

General Idea, Test Tube (1979)

Julie Carson, “Now, then and love,” 163.

Ibid., 160.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Not coincidentally, each group has included Hayes within various projects, further demonstrating the social and discursive connections that inform their intertwined pursuit of art practices which highlight the politics of queer subcultural life.

See →.

For more on this interpretation of this genre, see Claire Bishop,Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship(New York: Verso, 2012).

Interview with the author, March 22, 2009.

Ibid.

Many of the artists who regularly work with LTTR and Ridykeulous also work with a number of queer of color social outreach organizations, including the Silvia Rivera Law Project, Queers for Economic Justice, and FIERCE, a member-led organization devoted to developing leadership and community improvement for queer youth of color. Each of these organizations include art as part of its outreach, and artists donate work to benefit auctions.