1. Mental Institution

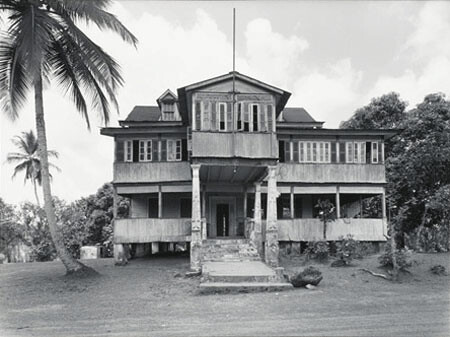

In the annals of the Arkansas Lunatic Asylum, the very first patient arrives several days before the facility—a multi-storied, Victorian brick edifice—officially opens in March 1883. The state’s first and only public zoo is built next to the asylum in 1926, and at first it houses exactly two animals: an abandoned timber wolf and a circus-trained bear, whose calls carry into the asylum at night.

The bear and the wolf. We’re suckers for things coming in twos, for not forging ahead alone.1 But every mental facility has its first patient: an Adam, an Eve, or an Adameve, stepping or pushed singular into the void of a space still unmarked—without vibration, without community.2 There were instances in which there was no singular first; in nineteenth-century Canada, inmates from one mental institution were borrowed to provide the necessary labor required to build another. Once the building had been completed, these same patients were secured in a structure of their own making but not their own design.

What does it mean to make an institution? To toil unpaid within a mechanism that is not your own? The inmates of one North American ward crushed excess grapes for a wine they could not drink. Despite the fact that the asylum operated without currency, this communally-built site—replete with hallucination and its own harvest—did not equal a hippie paradise. From a distance, this place could be perceived as inherently progressive, but its patients and staff shared an internal narrative, one that ideologically frames a form without horizons. For the patients, this institution appeared to have no limits. To exit institutionalization seems impossible if one cannot configure from within it how one lives without it.

What is repressed in artists’ exploration/flirtation with both undoing and rethinking institutions? Here, I have placed the mental institution at center, but if the mental institution is an impossible material when it comes to the labor of artists that harness the sociological imagination to tread against and away from bureaucracy’s material organization of power, what is revealed by the unsuitability of the mental asylum as artists’ supply?

In nineteenth-century North American psychiatric facilities, labor was often compulsory and unpaid, the facilities were overcrowded, and patients were held without consent. But what would consent have felt like within any institution? What forms of self-organization would be adopted by those who have loosened their relationship to a fixed social reality, by those who have been forced into the institution for demanding another social reality? In the history of madness, who has sanely asked to be let into an institution, to be held without touching?3 And yet, more often than not, one finds the patient ceding his or her self over to it, whether it be a mental ward, a prison, a school, or a museum. Especially for Americans, the institution has become as natural as sky, land, and empire; nothing else exists. Or rather, we fail to imagine how we will fruitfully exist without imperial institutions.

When an empire is lurching to a halt at its very end, it might be the moment when it begins, or is forced, to re-imagine its relationship to a national insanity. “The institution is ill,” said Dr. Jean Oury, mentor of Félix Guattari and founder and director of La Borde—an experimental psychiatric hospital in France that opened in 1951, just before the Algerian War, while France’s colonies were dispatching their “Gauls” during the Indochina War. If the institution is ill, the logic is that it can be repaired; but does Oury refer to one or to all—to the prison, to the mental ward, to the school, to government at large? If these forms couple, the recombinant hybrids can both reinforce and undo the former instrumentalizations of its wards in unpredictable ways.4 But the real, unanswered question here concerns whether, in forms singular or doubled, formal institutions can operate outside of state structures? La Borde comprised an attempt. Oury and his doctors dismantled the architectural separation between patients and administrators by placing the offices within the wards and inviting patients to be administrators (but not doctors?). Finally, the rhythm of La Borde did away with the capital economy of speed; Oury waited for fifteen years for one female patient to smile—and that fifteen-year smile was reportedly satisfying. Does the smile occur long after France has lost its colonies? He does not tell us.

It is worth considering that the fifteen-year smile—or the treatment that brought it about—might have been bankrolled by the raw materials generated within the colonies occupied by the very same state that supported La Borde. Allow me a partial fantasy: a French businessman trades in West African gum arabic, in peanuts, in fabric, and in gold. Regardless of his successes, his daughter is comatose. Nothing moves her. The businessman will try anything, but his capitalism cannot revive her. But perhaps a site like La Borde can use his business capital to fund its experimentation with a power structure that is not completely aligned with state policy. But once the “daughter” has left the asylum, calibrated, why would the millionaires continue to shell out? Potentially, state and corporate powers sanction and support the creative destruction of the institution—on a micro-scale—because such labor distracts revolutionaries and troublemakers.

Each institutional form organizes its errant citizens by making them captives, because they effectively disorganize communal life when left to their own devices. In the southern wilderness of France, an experimental educator named Fernand Deligny lived with autistic boys that his colleagues had disregarded, dubbing them “unmanageables.” Deligny referred to them as “radical others,” and he asks how we (unradical others?) can move near and with the radical other. In this instance, autistic space (as Deligny coins it) is generated and maintained by the unmanageables, marking a field of difference within a familiar landscape, within the geographical and ethnic boundaries of a singular nation. It is here that unradical others might enter and negotiate neurologically atypical forms of communication with the castoff sons and brothers of their fellow countrymen; it is where the mental institution and its architecture have been shed, but the state remains.

According to one interpretation of psychiatric history (informed by Fanon and driven by Foucault), colonial empires utilized mental wards in order to negotiate the least mitigated symptoms of native resistance. During the British occupation of Zimbabwe, one mental institution patient refused to call Europeans anything but “Eskimo.” His explicit naming of their foreignness momentarily amplifies their difference—in geographic relation to Zimbabwe, he has identified the colonizers as being from the edge of the planet and beyond reasonable proximity. By using a surreal means of exposing the colonizers’ excessive foreignness, the patient indicated that although he is a “guest” within the institution, he is neither a guest nor a foreigner within the land.

His illogic is a logic in the illogic of his incarceration, specific and national. To reverse the fact of being proclaimed foreign in one’s own land. It is a refusal of the guest status of insanity within one’s own culture. In the women’s quarters of the same mental ward, the higher-functioning White patients are serviced at the “Fair Lady Salon,” where they receive their traditional “Eskimo” hairstyles.

The institution hallucinates. It hurls itself both toward and away from the society at whose threshold it is placed. The terms “Eskimo,” “Foreigner,” “European,” and “Fair Lady” all get swapped—not because they are interchangeable, but because each is a smokescreen used by exterior forces to force themselves across a border. I imagine that there are patients in contemporary American psychiatric wards who have begun to call all of the doctors and their staff “terrorists”; would these patients then be patriots? In this psychiatric imaginary, the authorities are “radical others”—but they are not the same as the patients. Neither feels that they can pass from one type of radical other to another, or that this passing would be advantageous; after all, such a swap would still not take the doctor and the patient outside of monstrous structures.

2. Detecting Others

Before the shadow of that undone Adameve crosses the institution’s threshold, there is a domestic story of madness to be told: a story of the mad man, the mad woman, the errant sister, the undone father who thrashes through the family. Now, do we dare reject the institution as holding tank for family members that would otherwise dismember a family? The reality of their violence hardly clears the way for fearless love, sustainable renewal, and equal relations. Would such intimacy with insanity hinder a philosophical transformation of diagnosable illness into an anti-colonial stratagem? Perhaps, but let us first anchor this claim with an example of a person whose hallucinations might clinically qualify as delusional, but who is now held in high esteem as a potential liberator. Despite being responsible for many deaths, Nat Turner—who read an apparition of drops of blood on corn leaves as a hieroglyphic for revolt—comes to mind. While thunder rolls and the sun darkens, a voice clearly articulates, “You are called to see.” Are those who slave without protest, plowing dutifully, actually being plowed under by their sanity? Here we find the crazy brother as righteous brother, with the gory botanical hallucination/illustration marking the double ability to recognize inequity and act upon it as well. The hallucination is a vision, and also a transitory drawing that drafts bodies into action. Southampton, Virginia; August 21 and 22, 1831. The demand for another social reality should not, and cannot, be read as sheer madness.

Let us return to a place not beyond, but beside the institution, in Arkansas—not in the capital (with its zoo and its asylum), but beside the Mississippi River, in West Helena.5 There are cotton fields but no mental ward in the Delta of the early 1930s.6 Area radio broadcasts will not broadcast Black musicians for another ten years; the official sound of the night is White. Situated within all of this is a sharecropper’s dog-run cabin, where my great-grandmother, Fanella, is thirteen years old and newly married. Her husband, my great-grandfather, Jewel, returns unnoticed from picking cotton in the cotton field. He Blacks his hand with shoe polish from elbow to fingertip and hides under his young wife’s bed and waits in the dark room. As Fanny crawls into bed, Jewel grabs her leg with his blackened hand. Fanny screams, and the household comes running to her aid, only to discover her White husband with one Black arm, rolling on the floor laughing.7

It’s heady racist fiction as entertainment in a powerless shack: blackface has migrated to a hand belonging to a White man, conjuring rape by a Black man in a singular action. But Fanny’s scream is multilayered, for it was not rape that she feared, but detection. Fanny’s mother is, in fact, not White, and the pitch of her scream fell from the terrifying prospect of an end to racial passing, when the Black hand would locate her and claim her as its own.8 There must be shoe polish on her pale fat ankle. Her husband has revealed her in his minstrel gesture. All laugh hysterically—and it is hysteria. It’s the joke stoked by deferred trauma, the hubris of claiming Whiteness for one’s own in a town where the consequences of detection as a racial impostor could surpass the violence one endures for being Black. It’s the hysteria of passing for White in a county where middle class White men toy with “passing for Black.”

At the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, W. E. B. Du Bois’s albums of photographs of African Americans in Georgia featured staged portrait after staged portrait of anonymous women and men selected to represent African Americans in the American South. Conceptually, the subjects are in accord: each represents Blackness. However, it is apparent that some could choose not to. A colleague of mine recently pointed out a portrait of a young man I had selected to be in a 2004 issue of the journal Women and Performance focusing on the theme of passing, and remarked that he could have been my brother. I recognized my jaw, my cheekbones, and my hair, but whereas he looked honorable (upright, formally dressed), perhaps I did not. My ancestors had passed into Whiteness and I would not pass back. To turn back would be yet another dishonorable turn, read as trespass rather than return.

In my family blackface story, the psychological contagion of passing is passed between husband and wife. Although she screams, the man who has assisted her passing by marrying her is frightened as well. Will blackness, and its attendant vulnerabilities, claim her? Will it claim him as he has made it claim his hand? He craves and fears the return, crafting a household gag to cope. He engineers group therapy without even realizing what he is after: for Whiteness to be returned to her and to him. Group therapy in negative might staunch the contagion. But her race may not be the sole root of his concern; for he himself may not be as White as he claims. In the litany of his own ancestry, he includes the false ethnic category of “Black Dutch.” Together, their whooping and giggling signals their release from a field of racial possibilities into a field of institutional possibilities.

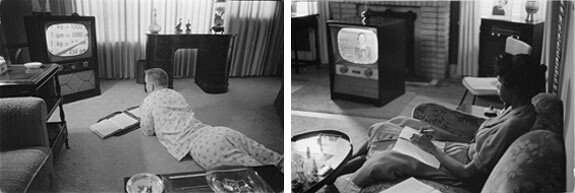

In boarding school, I was assigned to read what was then considered the first African American novel in the United States, Frances Harper’s Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892).9 A stock situation in Black Victorian literature is the moment(s) when a character refuses to abandon their race, and Iola Leroy is no exception. My professor did not broach the subject of how we scholarship students might be similarly coaxed into abandoning our class, and why we may decide not to. But in the book, Harper describes the ethical position of holding out: “But he was a man of too much sterling worth of character to be willing to forsake his mother’s race for the richest advantages his [White] grandmother could bestow.” He was honorable, too. Later, I would watch Imitation of Life (1934 and 1954), a Hollywood film that charts the ruinous path of a girl who breaks her mother’s heart in an attempt to pass out of Blackness.

Unlike the 1934 version of Imitation of Life, in which Fredi Washington (founding member of the Negro Actors Guild of America) portrays Peola, the 1954 version stars White actress Susan Kohner. In one scene, Kohner, as Sarah Jane, stages her own convoluted blackface—a White woman portraying a Black woman pretending to be a White woman of a certain class masquerading as another class of Black woman.10 This mise en abyme embodies a kind of bogeyman for those who have multiple origins, who fear they cannot land, who are endlessly refracting.

3. Soft Institutions

But inside of institutions, whether asylum, prison, juvenile hall, army, or college, my finally-White and never-rich kin were not and are not repaired. Will an artists’ temporary institution do the necessary psychiatric trick? After all, who gets to experiment with their mental liberation outside of hierarchies? How do we visualize passing as it applies to race, class, or a combination therein, and in a way can that alter the institution? Despite the “new beginning,” these Adameves have not yet forged or found an institution capable of repairing them: no prison or juvenile hall, hospital, military base, college, or museum can do it. Some will simply enter formal institutions and artist projects as White people, unrevolutionary and undone.

Which overarching governing forces heal whom, and which class of people are they meant for? Are we returning to Oury’s premise that institutions do not repair their citizens when the “institution is ill”? When the Supreme Court ruled in 1954 that segregation in schools was unconstitutional, the lawmakers of Sheridan, Arkansas bypassed the ruling by forcing all Blacks to reside outside of the town, effectively making Sheridan’s schools White-only. Cauleen Smith’s sculptural video work, Remote Viewing (2011), is built around this incident. Following this forced migration, a hole was dug in front of the town’s former Black school, and the building was pushed into the hole and buried. Town zoning stretched laterally and not vertically, and Smith points to the double construction of interior and exterior crypt, reconstructing the moment when the town engineered its own psychosis. The school bell begins to ring as the building tips over. It seems to be an utterance, but it is not Smith’s. She is careful to assert: “That story does not belong to me. It simply infected me, and the film was a way to burn off the fever.” Here the artist heals herself of an institutional infection. When the institution chooses amputation, she chooses recovery.

The artists who make pretend institutions (temporary schools, fake agencies, and so forth) rarely set out to invent little prisons or workable nuthouses that serve real people—really crazy, really violent. It is possible that artists are not equipped. Artists are comfortable making objects that document institutions, and they make objects (relational or otherwise) that perform the liberated institution.11 Another manifestation is the object that is liberated by abandoning the institution, just as there is the object that believes it can liberate the institution. As I do, these artists flirt with soft institutions, playing with the remains of madness—touching it lightly, quickly, and then moving away. In Paul Thek’s notebook he scrawls: “Institutions were formed for lack of spontaneous love.” To dilate his line of thought, we could move countercurrent to the institution, not by forming another organization, but by saying, as Thek does: Let me nurse you. Let me defend your body and your spirit. Let me bathe and bury you.

The Institute of Racial Passing. The Bureau of Escape (or is it a museum?). It’s an impossible organization: archaic, unfunded, and unspeakable. It’s a space that moves with those who stand at the threshold of race and class and gender. It asks how deeply the invention of an institution can move and whether making art—relational or material, professional or amateur—can attend to the insanity of passing? The artist who plays with institutions won’t touch this false storefront. But as artists recast the institution in the loving throes of utopic impulse—rhizomatic, perennial, untrammeled, and operating in some self-modeled notion of the future perfect—I still want to know whether the wake of their efforts reaches a margin, an unattractive demographic, a space unutterable. I’d like to see the articulation of an institution that traces or excavates the shared political dimension of radical others and passing, that considers the application of insane measures toward producing another social reality.

At nights, when doctors and attendants hear the zoo animals roaring and howling as they approach the asylum, they know that the patients will be agitated and that it is “going to be a bad long night.”

Adameve n. an individual who refuses to ascribe to one gender or another from the very beginning.

An institution that “touches” would operate under the rubric put forth by Jean-Luc Nancy when he writes about sex: “There is no such thing as penetration, only touching.” The institution without penetration would carefully and slowly determine how the surface of its intentions moved against the surface of their participants/clients/citizens’ vulnerabilities. It would not override the emotional structure of a tentative and weird singular being.

A number of instances exist in which institutions combine or rise within the remains of the former. In Los Angeles, for example, the country jail includes a wing for mental patients. The asylum and the prison fuse.

West Helena is the town where future novelist in a rented room after his Uncle Silas was murdered by white men in the middle of the night. Living in West Helena in 1918 “under the threat of violence,” Wright saw himself as the “victim of a thousand lynchings.” Passing was not an option. He headed norh, and eventually east to Paris.

These institutional possibilities include suffrage, and protection from the police. The poll tax of 1892 effectively dispatched with the brief window of enfranchisement after the Civil War. In the summer of 1919, after black sharecroppers had gathered in a church to discuss unionization, whites murdered over a hundred black sharecroppers from Elaine and West Helena. In 1921, the Ku Klux Klan was aggressively recruiting in Phillips County as well as nationwide. In Phillips County, lynching rates were “comparatively” low, but some claim this was not so much progressive as it reflected the manner in which local blacks had adapted survival strategies in response to reported extreme police brutality.

The family retells the story for seventy more years, decades after migration from West Helena to the West Coast, because it’s their creation myth. They left Helena long before the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) attempted to integrate Habib’s Cafeteria, opened in 1888 by Syrian immigrant Habib Etoch, long before Robert Miller became Helena’s first black mayor in the 1990s. The site of their peonage fused to the notion that to be raced is to be powerless remains static for them because they have not returned. And yet, the return might not shift any sense of whiteness as indemnity. Helena is situated in Phillips County, the poorest county in Arkansas, and over 60 percent of its inhabitants are black. In November 1963, at Habib’s, the demonstrators were arrested and their leaders were charged with “inciting to riot.” “Across the street, Habib ran a (whites only) private zoo, which housed deer, a pelican, wildcats, and monkeys.” Whenever the latter escaped, the animal were suddenly visible to all citizens, who touched them in the process of handling them. The deer is held by black hands, this once… See Robert Whitaker, On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice (New York: Random House, 1999), 68.

See →.

It is actually the second.

Here the infinite instability of race tangles with a longer philosophical tension between the optical and the oracular; in other words, believing in what is self-evident to the eye versus the abstract contextualization generated in and through speech.

An object, not institution, that describes passing fluently, clearly, and carefully is Courtney Smith’s Psiche Complexo (2003), a sculpture constituted of early twentieth-century Brazilian bedroom furniture. Here, the materialization of how passing is psychologically structured unfurls – the armoire, vanity table, stool with cushion, and two side table cabinets were initially crafted after European models by Brazilian furniture makers – they substitute tropical woods. Now, severed and then hinged together again, the pieces sometimes form one central body, able to hold each element, folded and collapsed within. Passing feels like this, at its best. Oswalde de Andrade’s Cannibal Manifesto (1928) and Smith’s source furniture come into being at roughly the same time, yet their metabolization of colonization are at odds. De Andrade’s ribald text, clearly a precursor to post-colonial critical theory, suggests a path where things pass through a body rather than constitute one. “I asked a man what was Right. He answered me that it was the assurance of the full exercise of possibilities. That man was called Galli Mathias. I ate him.” Here, eating Galli Mathias translates as consuming “the nonsense of scholastic reason.” It cannot become him or cling to him. De Andrade’s refusal of the internalization of Western institutions – psychological, penal divine, or literary, includes the mental bulwarks of passing. He ends: “Against social reality we are complex, we are crazy, we are prostitutes and without prisons…” De Andrade cast his bets with the imaginary and he wishes for a future without institution, of our own making and our own design. Although Smith chronologically follows de Andrade, her piece embodies a rather indexical form of art making. She points backward, toward what existed, when your body was institution. The indexical versus the imaginary. The object that documents an institution versus the object (relational or otherwise) that believes it can be an institution and be liberated. Versus the object that is liberated because it abandons the institution and, last but not least, the object that believes it can liberate the institution.