Shrooming

In what can be taken as a symbol of resilience, the matsutake mushroom was the first thing to grow from the ruins of Hiroshima. This incident, whether apocryphal or not, provides a fitting coda to a tragedy: under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, matsutake persist.1

Of course, mushrooms played another role in World War II, helping a fledgling state in Transcarpathia survive for eight years. The region had been part of the Czechoslovak Republic until a series of events on March 15, 1939 precipitated its secession. First, the Germans occupied Prague and claimed control of Bohemia and Moravia, then Slovakia (already apprised of Hitler’s intentions) declared independence. Necessity being the mother of invention, the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine was born.

The history books state that the republic lasted for just a day, stamped out by Hungarian forces acting with Hitler’s blessing. Disbelief and omission yield this tidy account. We learn nothing of how the Hungarians were actually rebuffed, nor of a later meeting that strengthened the republic’s ties with the Germans. Nothing of the hunting trip where Hitler shared plans for a second Hungarian offensive, nothing of the republic’s alliance with mushrooms and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, of the second rebuffing of Hungarian forces, of the partitioning of Uzhhorod, of the militarized trout that defended the river border. Certainly nothing of a gruesome chapter, starting in 1941, when the mushrooms experimented on the human population of Mukachevo to make a “Universal Carpathian Soldier.” The Red Army arrived in October 1944, and the Soviet Union absorbed the region two years later, bringing this period of interspecies statehood to a close.2

Surveying

I’ve been thinking about the counterfactual. This thought experiment, which imagines an alternate route that history could have taken, is experiencing a renaissance. Donald Trump deserves some of the credit. Last year’s miniseries The Plot Against America, adapted from Philip Roth’s 2004 novel, charts the rise of fascism, anti-Semitism, and xenophobia in 1940s America had Charles Lindbergh (the original advocate of “America First”) become president. In the 2019 version of The Watchmen, reparations for racial injustice stoke white supremacist animus. The series stops short of progressive wish fulfillment, however: the heroes of the day are police.

These examples, along with recent scholarly publications,3 suggest that the counterfactual might have more to contribute to contemporary discourse than right-wing magical thinking. An “alternative fact,” in its expediency and situational flexibility, is different from a heuristic reworking of the past, which can disrupt what John Stuart Mill calls the “deep slumber of decided opinion,” suggesting ours may be neither the best nor the only possible world.4

The counterfactual is commonly associated with speculative fiction, as if to imply that, once the paths start forking, it stops doing “serious” historical work: alter the cause, and what awaits is the chaos of contingency. This claim belies the practice of creating counterfactuals. Deviating from the record is no inconsequential act. It requires knowledge of the past, a sense of imagination, and readiness to grapple with theories of history: to consider whether individuals shape the course of events, or if systemic forces render them inevitable—to ask fundamental questions about necessity, probability, chance, and free will.5

Workshopping

Over the past year, I’ve run a few classes and workshops dedicated to the counterfactual.6 Collaborating in small groups, we would play out various scenarios, working from prompts given by participants. What if high-speed internet was never developed for consumer use? New York got bailed out in the 1970s? Al Franken’s resignation unfolded differently? Tea had never been discovered? Two of our scenarios are summarized in this text. One of them, titled “Shrooming,” began the essay. The other comes later, under “Ghosting.”

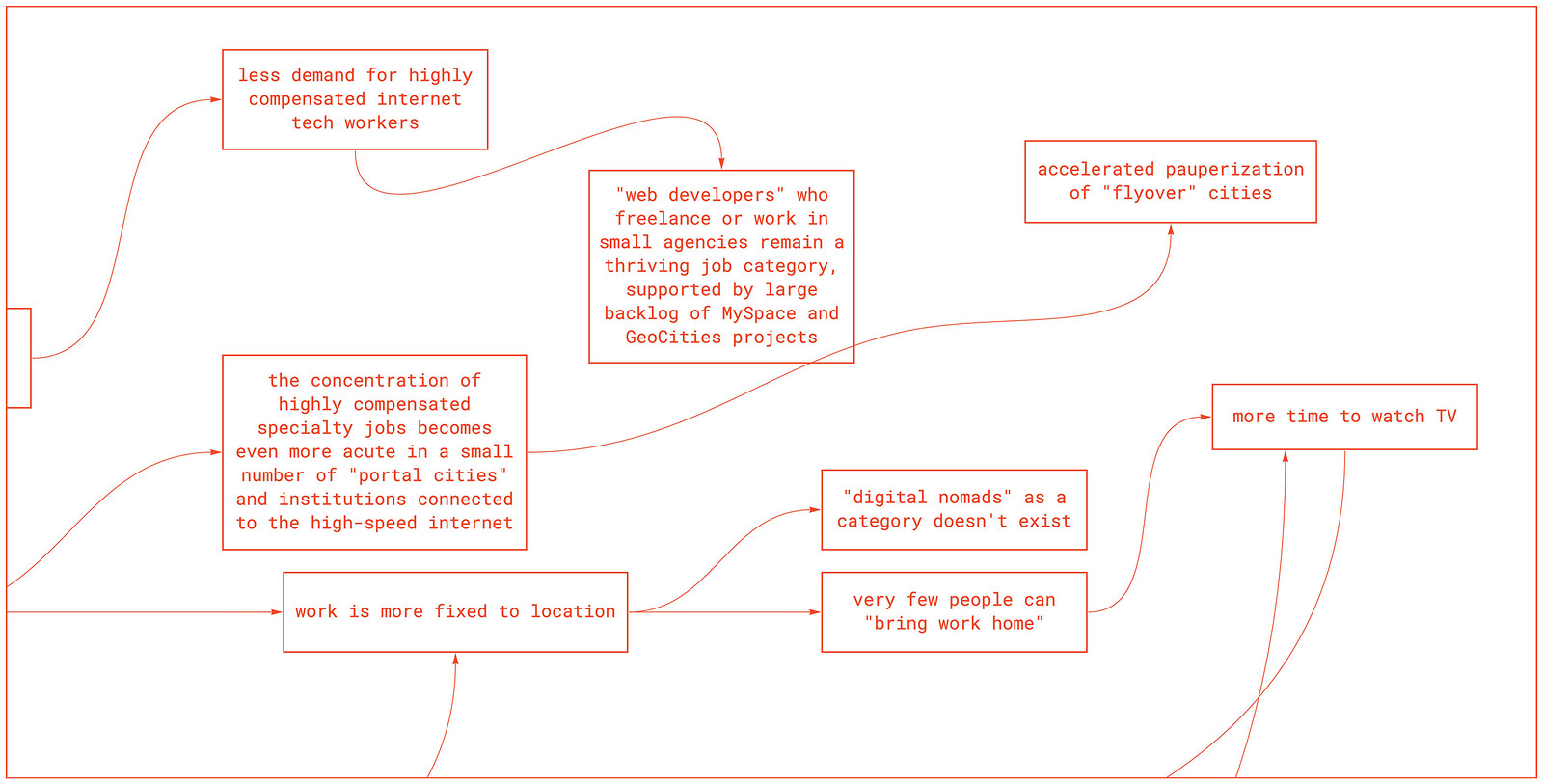

Our games often proceeded chronologically—which is not to say cleanly. As shown in some of the accompanying images, causal chains would fly around. Boards turned thick with details. We endeavored to survey decades or centuries, but were lucky to get through a handful of years. Branches grew trees that grew branches …

In one scenario, we imagined that the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty led to global nuclear disarmament, then considered the domestic and international effects. Much was left undeveloped, though an interesting thread emerged: as the specter of nuclear apocalypse dissipated, so too did the perceived threat of communism, leading more Americans to question their involvement in Vietnam. George McGovern rode this antiwar wave into the White House in 1972, withdrew troops the following year, and cut annual defense spending by 37 percent. Those funds (approximately $137 billion) went towards the country’s first universal basic income.7

“Frustration” was a word some participants used to describe the gameplay experience. I often shared the sentiment. Expecting something akin to science fiction, where worlds can be built with considerable license, we instead found ourselves in a paradox. Stepping outside of history made us feel more accountable to it; we couldn’t hazard any divergence without first learning what we were diverging from. A prism refracting a line of light, this artistic process (though still rudimentary) might have greater application, helping us dwell in the complexities of causation; distrust the precision of hindsight; and locate moments in the past, when the sediment has yet to settle, that could lead us towards a decent and equitable present.

Repairing

There’s nothing particularly modern about the counterfactual; before the Common Era, Livy imagined an alternate history in which Alexander the Great invaded the Roman Empire.8 But the form we know today can be traced back to the Enlightenment, when secularization allowed for less theologically determined models of the world. Against Leibniz’s theodicy came Voltaire’s Candide, Pascal’s famous aphorism about Cleopatra’s nose, and Isaac D’Israeli’s “Of a History of Events Which Have Not Happened.” Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century military strategists created speculative war games, tracing paths untaken in historical battles. Legal theorists, drawing on John Stuart Mill’s writing about causation, made counterfactuals integral to criminal and tort law.9 The sine qua non or “but-for” test seeks to determine, in brief: But for the existence of X, would Y have occurred?

Only in the past seventy years, Catherine Gallagher observes, have counterfactuals’ legal and historical dimensions begun working in tandem: for instance, in reparations claims.10 The question, following sine qua non, is what degree of well-being a person or group would enjoy were it not for a given injustice. To determine appropriate types of material and symbolic recompense, we measure the gap between that parallel world and our own.

As a speculative endeavor with no standard protocol, the counterfactual must be custom-fit to each case. How do we hypothesize what might have happened to affected persons—and at what scale: the decisions of individuals, or the behavior of the group? If a claim is made by descendants, as with reparations for American slavery, how should our counterfactual respond to this primary event as well as to its ongoing systemic effects? At this point, we’ve only just begun. It’s maddeningly mycelial work. We may not arrive at precise solutions for reparations, but I believe that asking and elaborating such difficult questions can help in that process.

Reparations, legal scholar David C. Gray writes, should be “Janus-faced.” One side, turned to the past, compensates harm through “corrective justice.” The other looks ahead, seeing compensation as a foundation upon which to continually improve the conditions of those affected.11 In their 2020 book From Here to Equality, William A. Darity and A. Kirsten Mullen propose something comparable. Their model, unlike many previous ones, is nuanced in its retrospection, weighing “the physical and emotional harms of [American] slavery, the inherently coercive nature of the system, the denial of the ability to acquire property and some degree of autonomy, [and] the denial of control over one’s family life.”12 It also suggests ways that reparations can assist in long-term growth. A trust fund could be established, disbursing grants for homeownership, education, self-employment, and other “asset-building projects.” The endowments of historically black colleges and universities would grow.

Of foremost concern to Darity and Mullen is that reparations close the racial wealth gap, which reflects “the cumulative effects of racism on living black descendants of American slavery.”13 Their argument, while not explicitly counterfactual, shares common ground: it doesn’t measure the gap between parallel worlds but two groups sharing the same one.

Restituting

Once a year, the Omarian family gathers to celebrate Omar Saidou Tall, a scholar and commander who spread Islam through West Africa in the nineteenth century. The family spans Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, and Guinea—testament to the forms of heritage ignored by the lines drawn at the 1884–85 Berlin conference.

Tall is a controversial figure, as his descendent Hadja Tall writes. In declaring a jihad against nonbelievers, he targeted indigenous communities and French colonizers alike. His relationship with the latter shifted over time: Tall gained fame for his attempted siege of a French fort in 1857, then negotiated with colonial officials a few years later to ensure his continuing power in the upper Senegal valley.14

However the Omarian family remembers Tall, its gatherings are always incomplete. A number of his possessions are housed in French institutions, including more than five hundred manuscripts taken from his library in Segou. According to scholar Felwine Sarr and art historian Bénédicte Savoy, the family has sought the return of his relics—and the digitization of his manuscripts—since 1994. Perhaps owing to the visibility of their 2018 report,15 commissioned by Emmanuel Macron, one of Tall’s sabers was temporarily restituted to Senegal the following year. (It was originally seized from Tall’s son Ahmadou during an 1893 battle.) The decision for its permanent restitution lies with French MPs.

Had Tall’s relics and manuscripts never been taken, how would he be remembered? In a petition to the president of Senegal, the Baajoordo Research Center on African Intellectual Heritage provides one answer. The prominent representation of Tall as a power-hungry fighter, it argues, belies his investment in science, learning, and the humanistic dimensions of Islam. Contrary to what Sarr and Savoy write, the petition claims that digitizing Tall’s library isn’t enough. Its manuscripts add texture to the biography of Tall and are worth “more than any other piece of the Segou treasure.”16

Restitution, like reparations, brings about counterfactual thinking. The argument for return draws, in part, on an estimate of the effects of deprivation. To Sarr and Savoy, centuries of pillage, plunder, and “acquisition” have left many Africans “struggling to recover the thread of an interrupted memory”; any act of restitution should thus involve “memory work” and reappropriation—particularly for communities which have changed so significantly that the original function of artifacts may not be evident or applicable.17 These processes, Sarr told one of my classes last fall, enable “young Africans to inscribe themselves in a long history of creation and meaning production” and shape “a renewed imaginary of a future.”18 Possibilities once consigned to a counterfactual world can finally emerge in our own.

Ghosting

On November 7, 2020, desperate for any excuse to get away from our news feeds, my boyfriend and I went biking in Rockaway, Queens. We found a spot of sand beyond the reach of cell reception and did our best impression of beached seals.

On returning to the ferry, we sensed a change in the atmosphere. Sounds, at first barely audible, began to rise above the drone of the sea. A string of honks. Echoes, then cheers. Signs of relief, and also one of consternation: there was a man on a balcony turning the American flag upside down. Flapping alongside it were two identical banners, printed with meshes of blue and white lines.

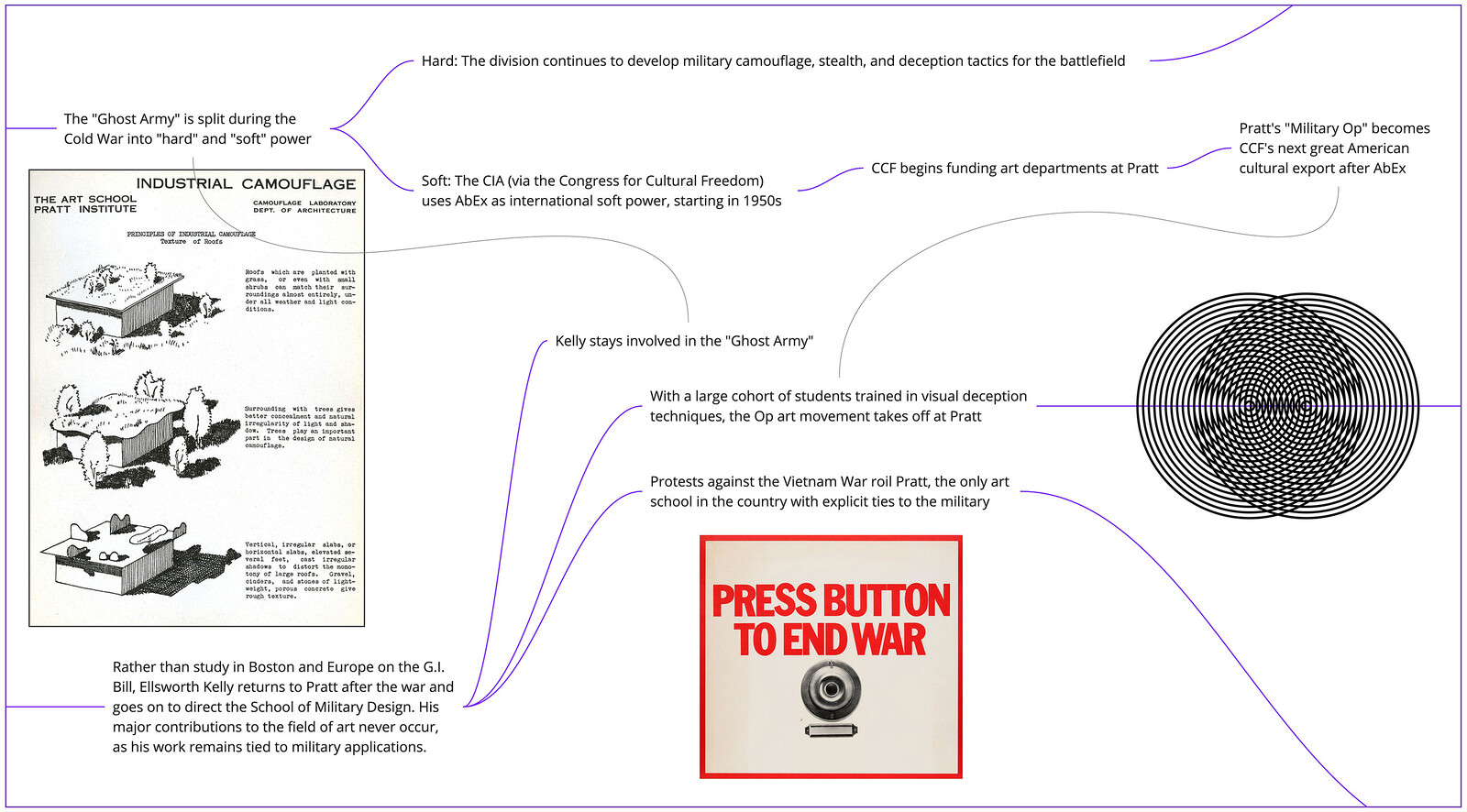

I had seen the banner before; it was made by the former dean of the School of Military Design at Pratt. The SMD dates back to World War II when the institute, rising to meet the moment, ran an Industrial Camouflage Program and recruited students on campus. Five alumni of the time, including Ellsworth Kelly, became known for their service in the “Ghost Army,” a unit that employed creative tactics—inflatable tanks, phony radio transmissions, even fake generals—to deceive German forces. Pratt leveraged their success and built lasting ties with the military, creating a new model of art school.

The SMD curriculum isn’t limited to subjects with military use. Funding from the Congress for Cultural Freedom has fostered generations of artists, many drawing on the visual language of camouflage to create what’s (cheekily) known as “Military Op.” “Dazzle the collectors (and the commies),” the saying goes.

In the interest of full disclosure: I’m an adjunct professor at Pratt. From what I can tell, the SMD never had a specific ideological agenda. Many universities enter into compromising situations when they accept military funding, and I don’t feel that Pratt should be held to a different standard just because “Military Op” is now synonymous with alt-right aesthetics. Still, when I saw those patterned banners at Trump rallies, making waves of moiré effects—they gave a different meaning to the term “collective hallucination.”19

Gaming

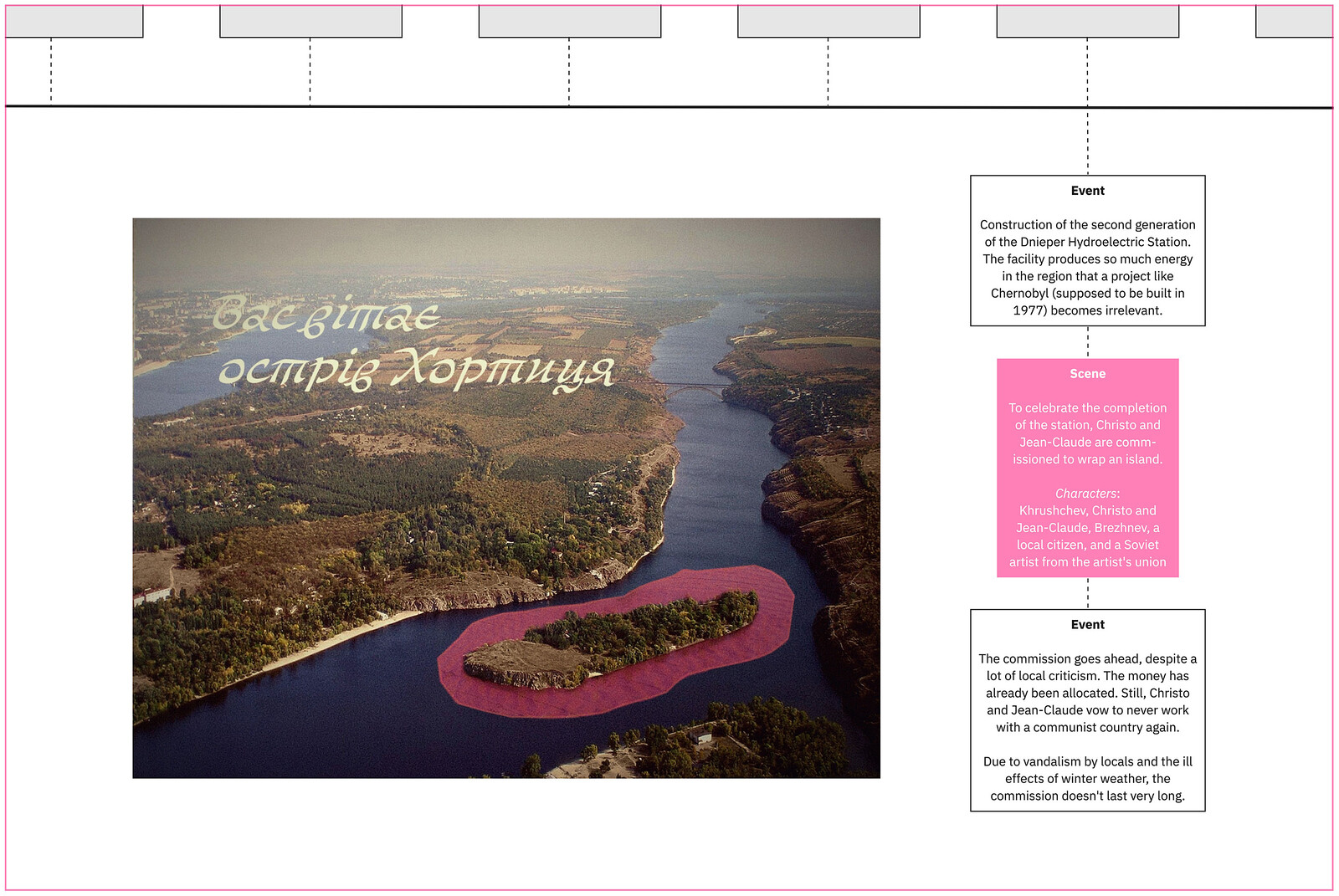

For my latest workshop, I changed the nature of the game.20 The counterfactuals of previous workshops played out in linear time, so I was curious to see if a looser approach would affect the stories we told. To this end, I worked with Microscope, a “fractal game” created by Ben Robbins in 2011.21 Players begin by setting start and end periods, then build their world in whatever temporal order they choose, scaling between periods, events, and intimate scenes, where they can role-play as different characters.

The first section of this text (“Shrooming”) is an example of this looser approach. We commenced with the pragmatics of war then turned to mushrooms and trout, as if the freedom from chronology also freed us from having to be plausible. Something was lost and something gained in the process. The rules of causation weakened as our flair for storytelling grew. We left the peripheries of history and crossed into the domain of magical realism, where the supernatural is part of everyday life—worlds real and possible fold into one another.

As for the mushrooms … well, consider the mosquito. The insect, a constant meddler in human affairs, killed off half of our species. The mosquitos of Panama cut short the life of a Scottish colony, while those of Walcheren served Napoleon, who saw malaria as a potent weapon in his arsenal—a disease made from breached dykes and brackish floods which could lay waste to English soldiers.22 Who can say if mushrooms, in turn, didn’t contribute to the events in Carpatho-Ukraine? When we keep focus on human actors, we ignore our other allies and enemies (however wittingly or unwittingly they participate).

Perhaps “magical realism” is a misnomer. After all, Gabriel García Márquez insisted that he was not a magical realist but a social realist, echoing a claim by one of his characters that “if they believe it in the Bible … I don’t see why they shouldn’t believe it from me.”23 Populating a game with things mythic, conspiratorial, counterfactual, and untrue is like holding a convex mirror to the world: no matter what bulges or shrinks, everything is captured. We live with our fictions.

This account comes from Anna Tsing, who thought the story was an urban legend until a scientist confirmed its existence “in Japanese newspapers in the 1990s. I have not found it yet. Still, the timing of the bomb in August would have corresponded to the beginning of the matsutake fruiting season.” See The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015), 290.

Adapted from the counterfactual game “What If Carpathian Ukraine Survived as an Independent State from March 15, 1939–1946?” Conceived and played by Attila Hazslinszky, Anastasia Kostiv, Petro Ryaska, Anton Varga, and Tyler Coburn as part of “Counterfactuals,” a workshop for Cultural Capital Introspection / Sorry No Rooms Available, Ukraine that ran from September to October 2020. This summary takes some poetic license with the game and doesn’t capture all of its complexity.

See Catherine Gallagher, Telling It Like It Wasn’t (University of Chicago Press, 2018) and Christopher Prendergast, Counterfactuals: Paths of the Might Have Been (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019).

John Stuart Mill, quoted in Prendergast, Counterfactuals, 62.

I’m grateful to Siqi Zhu for his help in thinking through this section of the text.

This project began with a class called “Counterfactuals” at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, which ran from March to June 2020. Subsequent workshops of the same name were held at Wendy’s Subway, New York (July–August 2020) and Cultural Capital Introspection / Sorry No Rooms Available, Ukraine (September–October 2020).

Adapted from the counterfactual game “What If the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty Led to Global Nuclear Disarmament?” Conceived and played by Alex Kim, Brittni Harvey, and Tyler Coburn as part of “Counterfactuals,” Wendy’s Subway, New York, July–August 2020.

This anecdote comes from Gallagher, Telling It Like It Wasn’t, 17. Much of this section draws on Gallagher’s excellent book.

See John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic Ratiocinative and Inductive (1843; Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Gallagher, Telling It Like It Wasn’t, 6.

David C. Gray, “A No-Excuse Approach to Transitional Justice: Reparations As Tools of Extraordinary Justice,” Washington University Law Review 85, no. 5 (2010): 1043–1103.

William A. Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen, From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2020). Darity and Mullen survey reparations models from Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch (“Who Pays for Slavery?” 1990); Larry Neal (“A Calculation and Comparison of the Current Benefits of Slavery and the Analysis of Who Benefits,” 1990); Thomas Craemer (“Estimating Slavery Reparations: Present Value Comparisons of Historical Multigenerational Reparations Policies,” 2015); James Marketti (“Estimated Present Value of Income Directed during Slavery,” 1990); and Judah P. Benjamin (“You Can Never Subjugate Us,” 1860).

Darity and Mullen, From Here to Equality.

Hadja Tall, “Al Hajj Umar Tall: The Biography of a Controversial Leader,” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 32, no. 1–2 (2006): 73–90.

Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics (Ministère de la Culture de France, 2018).

Baajoordo Research Center on African Intellectual Heritage, “May France Want to Restitute to Senegal the Oumarian Library Undiminished!” petitions.net →.

Sarr and Savoy, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage.

Felwine Sarr, “Restitution of African Artifacts: History, Memory, Traces, Re-appropriation, New Ethical Relation,” VIARAV8301: Critical Issues (class lecture, Columbia University, New York, October 12, 2020).

Adapted from the counterfactual game “What If, Following WWII, Artists Continued to Be Integrated into the Military through a Permanent ‘Ghost Army’ Division?” Conceived and played by Alex Kim, Brittni Harvey, and Tyler Coburn as part of “Counterfactuals,” Wendy’s Subway, New York, July–August 2020.

This workshop was arranged for Cultural Capital Introspection / Sorry No Rooms Available, Ukraine, September–October 2020.

For more information on Microscope, visit →.

Timothy C. Winegard, The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator (Dutton, 2019).

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Year of Solitude, trans. Gregory Rabassa (1967; Avon Books, 1970), quoted in Magical Realism: Theory, History, Community, ed. Lois Parkinson Zamora and Wendy B. Faris (Duke University Press, 1995), 4.