The following testimony by Ailton Krenak, a longtime indigenous activist and intellectual in Brazil, was originally published in the December 2019 issue of the Brazilian magazine Olympio: Literatura e Arte. The testimony was related orally to José Eduardo Gonçalves and Maurício Meirelles, and then transcribed. It is preceded by a Foreword written by Meirelles, editor of Olympio.

Foreword

Standing at the podium of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies,1 speaking the white language perfectly, a young indigenous leader addresses the 1987 National Constituent Assembly with an unusual sort of speech. Having already been barred from entering the plenary in his typical dress, he wears casual Western clothes, a white three-piece suit lent to him by a deputy who is his friend, and holds a small container in his hands.

“I do not wish to disrupt the etiquette of this house with my demonstration, but I believe that …” He pauses, and begins to scoop a dark paste from the container with his fingers, which he then spreads on his face. “I believe that you, honorable members, can no longer stand at a distance from your aggression motivated by economic power, by greed, by ignorance of what it means to be an indigenous people …”2

Barely audible, a female deputy whispers: “But he is painting himself all black.” It is genipap paste, used by many Brazilian indigenous ethnic groups for mourning rituals. The young man speaks slowly, but with determination: “I think that none of you could point to aspects or acts of the indigenous people of Brazil that put the life or the patrimony of any person, of any human group from this country at risk …”

With a flat hand, he paints his cheeks, forehead, nose, and chin. Those in the room hear the sound of many cameras clicking. “A people that has always lived in the absence of riches, a people that lives in houses covered with thatch and sleeps on mats on the floor, cannot be identified, in any way, as a people that is the enemy of national interests, nor that puts any development at risk.”

The young Krenak finishes painting himself, and delicately places the empty pot on the podium. His face, all black, is now the same color as his shining head of hair, highlighting his bright white eyes and teeth. “Indigenous people have moistened with their blood every hectare of the eight million square kilometers of Brazil, and you, honorable members, are witnesses to this.” Thus, he courageously ends his speech. Before thanking the Constituents who observe him, stupefied, Ailton Krenak takes a long pause. Though his eyes seek something in an uncertain future, his body is rigorously still, as though he had just returned from a shamanic trance.

That speech marked the emergence of one of the most important activists of the many indigenous movements in Brazil; Krenak’s action was considered decisive for the inclusion of the guarantees of the rights of indigenous people in the 1988 Federal Constitution. In the same act, an artist was born: using his body as a territory for biopolitical action, Krenak anticipates, in that performance, some of the central preoccupations of contemporary art to come. He is also a writer who, loyal to the ways of his ancestors, weaves his stories at leisure, in the oral tradition—differently from whites, who write their words because their thought is full of forgetting, he says, quoting his friend Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman.3 And, above all, Ailton Krenak is a thinker.

Passing through disciplines that pertain to the tradition of Western thought—anthropology, ethnography, philosophy—as well as operating in traditions that oppose themselves to the latter—such as indigenous history and culture, and traditional arts and crafts knowledges—Ailton is a cultural shaman. That is, he possesses the ability to cross the borders between indigenous and non-indigenous worlds, administering relations between them. This quality is also present in his speech; he uses the pronouns “we,” “ours,” and “us” to refer either to collective humanity, in an ample way, or specifically to groups of indigenous people, depending on the context in which Ailton includes himself.

Master of an undomesticated thought that moves agilely in many directions, he is surprised by no question, and reacts with mocking indifference to some of them. In truth, he elaborates a commentary that, often, will only be finished the next day, and takes the shape of a parabola. If we borrow his concept of collective persons—a “cultural body” that perpetuates itself from generation to generation through orally transmitted stories—we could attribute to him characteristics of his ancestors, as reported by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda in his 1936 book Raízes do Brasil (Roots of Brazil): “Extremely versatile, they were incapable of certain ideas of order, constancy, and exactness.”4 Sophisticated and at the same time furtive, Krenak’s ideas hide under apparently simple sentences, like when he is asked if culture is an intervention into nature: “No, nature is an invention of culture”—a linguistic cannibalism of the rhetoric of Antônio Vieira (1608–97), in his Jesuit complaints about the inconstancy of the Indian soul: “Other peoples disbelieve until they believe; the Brasis [native Brazilians] do not believe even after believing.”5

For Ailton, “by always being able to tell one more story, we postpone the end of the world.” He did so with joy and patience—between puffs of rapé (snuff) from his wooden tipi pipe—over the two days of our meeting in Belo Horizonte, which resulted in the testimony below.

As he perhaps belongs to the category of “a people receptive to any shape but impossible to keep in one shape,”6 to quote Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, a question that we interviewers consider inoffensive could have an unexpected effect, transforming the interviewee’s docility into admonition: “Why are you laughing? Our worlds have been at war, from the beginning!” Seeing the astonished look of the interviewers, Ailton Krenak bursts out laughing and looks at us, in turn, with affection.

—Maurício Meirelles

***

Nature Is the Creation of Culture

It is only possible to imagine nature if you are outside of it. How could a baby that is inside its mother’s uterus imagine the mother? How could a seed imagine the fruit? It is from outside that one imagines the inside.

At a certain moment in history, the “civilized place” of humans conceived the idea of nature; it needed to name that which had no name. Thus, nature is an invention of culture, it is the creation of culture, and not something that comes before culture. And this had a huge utilitarian impact! “I separate myself from nature, and now I can dominate it.” This notion must have arrived with the very idea of science. Science as a form of controlling nature, which comes to be treated as an organism that you can manipulate. And this is scandalous. Because once someone thinks this, they damn themselves, don’t they? They leave that organism, cease to be nourished by the fantastic cosmic flux that creates life, and come to observe life from outside. And while humanity observes life from outside, they are damned to a sort of erosion.

I find it interesting that one expressive construction of modern thought is around the idea that nature and culture are in conflict with each other—many twentieth-century philosophers debated this idea. There is an enormous amount of writing on this topic, all of which is based on a confusion produced by thought that is logical, rational, Western. The scientific and technological disorientation that the West is now experiencing is the product of this separation between nature and culture.

Firstly, people create nature and separate themselves from it; then, they idealize it. For example, the conception of the Atlantic coastal forest, the Mata Atlântica, is considered part of this idealized nature. In reality, the Atlantic coastal forest is a garden—a garden constructed and cultivated by Indians.

White People Love to Separate Themselves

I think that the concept of Amerindian perspectivism developed by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro—the potential for different visions, from other places of existence besides the human—can also be applied in other contexts.7 It is a very powerful concept to help us understand the time in which we are living. If people were not in the situation of being divorced from life with the planet, perhaps this concept would only be a product of knowledge without direct implication for our collective life, or the sustenance of life on earth. But, in the stage of divorce we are in, with humans detaching themselves from here like a caterpillar from a hot roof, disconnecting as if they did not have any empathy …

It is absurd. It is as if a glass divider separated, on one side, the experience of the fruition of life, and on the other, the place from which we originate. This division reveals another, more profound divorce: the idea that humans are different from everything that exists on earth. And there is a type of person, a type of mentality, that detests the idea that people can live so involved in the daily life of the planet, without detaching ourselves from it. They think this idea weakens them, that it is a rejection of the imagined power of people to distinguish themselves from nature—to become people!—a rejection of this thing that white people love to do: to separate themselves.

Ecology Is to Be Within the Will of Nature

Recently, I met with a group of heirs from some very old, wealthy families. They said to me, “We want to create a fund to take our families’ money out of circulation, because this money is financing the destruction of the planet. We have been thinking of buying land in the Amazon and giving it to the Indians.” So, I told them: “Don’t do it! You will wind up making the indigenous move to places that are not theirs. That are not them, that don’t have the necessary ecology and their culture already within. You really want to detach? You cannot buy land, land is not a commodity.”

At this meeting, I talked about Chief Seattle’s letter.8 Some time around 1850, the western frontier of the United States was already devouring everything. The American cancer had already metastasized, had left the East Coast and come to the Pacific, where the Seattle tribe lived. I went to learn about the economy of this group of indigenous people prior to the arrival of white Americans. At that time, they lived off salmon fishing. Their beach was divided with rocks. The waves threw fish onto the rocks, and that’s how they would catch the fish. It is equivalent to an image described in a Caetano Veloso song: “An Indian raises his arm, opens his hand, and picks a cashew.”9 There was a time of year when the Seattle people fished. This involved the patience of looking for things. This is ecology: it is being inside the earth, within nature. Ecology is not you adapting nature to your will. It is you being inside the will of nature.

Is This a Body?

When the natives of this land saw the Portuguese for the first time, they had doubts about whether the Portuguese people had real bodies, that breathed, that sweat. A body! So, they took a few of the Europeans and drowned them. And waited to see if they would float, if they would smell. They waited and waited. They then began to suspect that yes, those krai, those whites, must have a body. “This could be a body,” they thought. After setting a body to dry, they watched and said, “It seems like a body.” They began to investigate the material, and the kind of spirit that inhabits those bodies. They asked, if one body was the same as that person’s, because that person could be in another body, couldn’t they? Or that person could be one of what the Krenaks [an indigenous group in Brazil] call nandjon—a ghost that has the nature of a supernatural being, or the ghost of a supernatural being. The natives investigated and discovered that the krais were not nandjon, but that they had souls of another quality: the master essences of gold, of iron, of weapons, of all the apparatuses associated with the tools whites use to meddle in the world.

Before we appropriated metal to make the tools, we were closer to our other ancestors, to all the other human groups that move the world only with their hands, with their bodies. When people began to string plumb lines into the earth, it produced the spirits that make the tools that impress their mark on the earth. It is they who are fabricating the Anthropocene.

The War to Exterminate the Botocudo Indians

In 1808, when Don João VI arrived in Brazil with the Portuguese court, the Doce River forest was like a wall of the sertão (backlands). It was necessary to conduct business over the Espinhaço Mountains so that the royal exchequer could control the flow of gold and diamonds between the mining region and the port of Parati. For this, the Crown created fear in the diamond and gold prospectors who came for land—they are the precursors of the deadly construction and collapse of the Mariana and Brumadinho dams10—saying that if they descended the mountains and became lost along the Santo Antonio River, near Piracicaba, and fell into the Doce River, they would be devoured by the Botocudos.11 Thus, the Botocudos began to be considered cannibals. But the Botocudos were hunter-gatherers who lived in the forest, bathed on the beaches, and ate cashew fruit. They experienced the cycles of nature profoundly, in a deep ecological relationship with the environment. This idea that we would kill and eat prospectors, miners, was a strategy of the Portuguese Crown so that the contraband trade in gold and precious stones would not take advantage of the natural exit by the coast of Espírito Santo, by the river—how would they monetize the entire Doce River forest? Thus, this image of the Botocudos beasts of prey hidden in the jungle was used strategically to keep that territory isolated.

The “lords of a province,” who in that time had already depleted the greater part of the gold and diamond reserves on their own allotments, then went to Rio de Janeiro and said to Don João VI that it was necessary to open the entrance in the Doce River forest—they already knew that there was gold and precious stones there. The settlers were persistent and, promising that they would fill the king’s coffers—which were empty—with the riches of the Doce River, succeeded in convincing Don João VI. At that moment, they entered the forest. But, consumed by fear of the Botocudos, they entered with an authorization of war: a letter dispatched by the king, declaring a war of extermination on the Botocudos of the Doce River.12 After that moment, a large mining concern began to set up barracks on the tributaries of the Doce River, and, from Itabira down, everything became barracks grounds. Each one had to have one military guard, at the least. They brought soldiers from Bahia, from Rio de Janeiro, from São Paulo, from Goiás, and also recruited Indians into troops. They also took the kin of tribes close to the Krenak to be soldiers.13

Why did Don João VI accept the settlers’ demand and make war against a people he did not know? This question should make sense since a bankrupt European Crown that had finished settling in these tropics authorized a war of extermination on the native peoples. As the settlers had promised the king gold and precious stones, that gesture—the Royal Letter that authorized war on the Botocudos—established a corrupt relationship: the Crown is corrupted by the settlers. And, together in this corruption, they set in motion a war to annihilate the original people, creating a false narrative that they were building a nation. And people believed it.

“Indian Plans”

In the years before the Constituent Assembly,14 before the means to guarantee the rights of indigenous peoples had been created, we felt the need to show the government and institutions that were still full of the rancidity of the dictatorship, that they were absolutely mistaken in relation to our presence—that we were not the rearguard, but rather the vanguard. “You are completely wrong, your sustainability program is a lie,” we told them. If we had not done this, the Constituent Assembly would have declared that the Indians were dead, end of story. At that time, there was discrimination even worse than today’s—at that time, they wanted to declare us dead; now, they wish to kill us! There existed, for example, a saying in bad taste that if you were to go out to have a picnic and it rained, that would be “Indian plans”; if you were traveling and your car broke down on the road, that was “Indian plans,” etc. So, language can be a vehicle for stereotyping, that secretes venom, can’t it?

Today, an imbecile with similar negative potency arrives in a place of power and what does he do? Making a mockery of anthropological and archeological research, he says that “petrified poop of an Indian” gets in the way of the country’s development.15 How can we relate to a world like this, wherein completely insane topics occupy the state apparatus and begin using the system to destroy life?

But if we look at this through another poetics, we will come to understand that the Indians will win. Because, if this state apparatus, since colonialism, never managed to settle down and remains growling and biting all this time, then it is becoming a ghost. This shows that the Brazilian state still has not managed to overcome this question, and that we will win this moral assault. It simply has not yet surrendered—it fidgets, spits, kicks—but we will triumph in time. And there’s no use wanting to negate this, because when the head of the nation makes a quip in bad taste about the petrified feces of Indians, he shows that he has not yet grown up, that he remains in the anal phase. The guy is still eating shit.

We Are Vile

I was in Roraima, on the border with Venezuela, with my Yanomami kinsman and with the Macuxi, the people from Raposa Serra do Sol.16 During my trip home, I took my seat at the window of the plane, and beside me sat a man with a small briefcase in his hand, full of documents.

Right away, his presence infused the air with lack: it was the emptiness, the despair, the pain of a Venezuelan refugee. I sensed his distress as he expressed a wish to make a request of the flight attendant—water, or something else—but did not know how. He, who had not bathed in days, turned to me and said in Spanish: “I am Venezuelan, my name is Jesús Herrero. I am hungry.” I told him that in just a bit they would be serving a snack. He looked anxiously down the aisle.

Jesús is a topographer and technician specializing in hydrology, but he could not find work in Venezuela for the past eight years. He had studied in Moscow, through an international partnership between the National University in Venezuela and a technological institute in Russia. When the snack cart arrived, which required payment, Jesús became completely frustrated: “I don’t have cash. For seven days, I was in Pacaraima.” In this city on the Brazilian side of the border, refugees are registered and hope to gain entrance to Brazil. He spent seven days there, sleeping in a shelter packed with people, until authorization manifested and he could get on a plane for Santa Catarina. Someone sent the ticket, which he will repay by working.

Beside me, Jesús was sinking into a void. “I can’t let this guy get crushed like this,” I thought, and I began to talk with him. I struck up a conversation about refreshing topics, mostly so that he would feel accepted, because I perceived that much of the suffering of refugees was that after they gained entry into Brazil, they were greatly mistreated. A national collection campaign had been set up, and when the donations arrived at Pacaraima, they were placed in a shed. The people on this side of the border went there and burned the shed. We set fire to storehouses of donations for suffering people and, eventually, set fire to the people themselves.17 We are not “cordial,” as Sergio Buarque de Holanda’s theory goes, we are vile!

To Get Closer in Order to Learn

I don’t believe that cities can be sustainable. Cities were born from the inspiration of ancient fortresses that served to protect human communities from bad weather, attacks by wild animals, and war. They are built as structures of contention, they are not fluid. In times of peace they become more permeable, but calling a place that confines millions of people “sustainable” uses a somewhat exaggerated poetic license. Some cities are true traps: if the energy supply there comes to an end, everyone dies—in hospitals, stuck in elevators, in the streets. Whites want to live sheltered in cities and do not perceive that the world around them is ending. They have been doing this for a long time and I don’t know if they know how to live any other way. But it is possible to learn other forms of living.

My friend Nurit Bensusan sent me a beautiful letter about these other possibilities of living. She is a biologist and works on public policy in the area of biodiversity. She is Jewish, from one of the branches of the ancient Hebrews, and comes from a culture that already passed through Palestine, through Turkey, through many places. Following these migrations, she went to Western Europe and then arrived in Brazil to work in anthropology, with forests and indigenous peoples. It was as though she had landed on another planet. Little by little, she came closer to this planet. Today she considers herself an ex-human. Nurit imagined a situation in which she moved the same distance that the other moved—this other who is from outside the city, who is from the forest. Like the Indians. She walks toward them just as they walk toward her, until they each reach the limit of their approach. There they stop and observe each other. Her letter is about this, about this other possible place of interaction.

People Who Sprout from the Forest

The Amazon rainforest is a monument. A monument built over thousands of years. The ecology of that place in motion creates shapes, volumes—disperses all that beauty. The Amazon rainforest, the Atlantic coastal forest, the Serra do Mar, the Takrukkrak18 are monuments that have, for us, the power to open a portal that accesses other visions of the world. The forest provides this. And yet, despite its materiality—its body that can be felled, uprooted as wood—the forest is not seen. In Brazil, there are cities that UNESCO has declared the cultural patrimony of humanity. Meanwhile, we destroy the Atlantic coastal forest, the Amazon rainforest. It’s a game of illusion.

The fact that we live in the region of the world where it is still possible to sprout people from within the forest is magic. There are people who look at this as a type of delay in relation to the globalized world: “We should already have civilized everyone.” But it is not a delay, it is a magic possibility! How wonderful that we can be taken by surprise when, at one of the borders with our neighbors—Bolivia, Peru, Venezuela, for example—a collective of human beings springs up that was never registered or inventoried, speaking a strange language and comporting themselves in a totally extravagant manner, shouting and jumping in the middle of the forest. The last time that a previously uncontacted group was encountered was six years ago.

Ancestral Memory

My ancestors always lived in deep ecological relationship with nature. In the spring, a season they loved, the Botocudos ascended along the Doce River to the steep slopes of the Espinhaço Mountains to do the rites of passage for the young men—boys from nine to twelve years old, the age at which they pierce their lips and ears to install labrets and earrings. The culmination of the period is September 22, when the sky is very high and the seasons pass from winter into spring. The mountains bloom, it’s beautiful. The Botocudo families, having come from different hillsides, from the Serra da Piedade, traveled to the Espinhaço to experience this cycle deeply. There is a lot of inscription about this engraved on rocks throughout that entire region. Have you ever noticed, on the slopes of Conceição do Mato Dentro, how wonderful the Tabuleiro waterfall is? The slopes of the Tabuleiro are a tremendous library! Once I stopped there to watch the sunset, until it grew dark. I stayed looking at the different stories on those slopes. It is the history of the passage of our ancestors through those sites some thousands of years ago, as archeological studies have already confirmed. Our ancestors were writing on the slopes and shelters at the same time as other civilizations were also leaving their records and deeds.

Our history is interlaced with the history of the world. But the country throws away this history. People who travel to these places drive pickaxes into the boulders, pull up signs, hang a fossil of a bird, a fish, or a rock painting on the walls of their homes as though it were a souvenir bought on the beach. Each fragment, each piece that they pull up from those rocks is as if they ripped out a page or stole a book from the library. It is in blatant disregard for our ancestral memory. A disregard so large that the possibility of a reconciliation of our idea of peoplehood and nation with the land becomes rejected. It is as if there were a split, a divorce between the land and its people.

A Forest That Floats in Space, Yvy marã e’ỹ, and the Wormhole

According to Yanomami cosmology, we are living through a third version of the world. The first was extinguished because a taboo internal to their tradition was broken, and in that primordial world, the sky fell and split the earth. The sky, though it looks light, is very heavy; it can fall and split the earth. Since then, the shamans have dedicated themselves completely to maintaining the supports of the sky. They are like architects in this cosmic engineering of building supports for the sky.

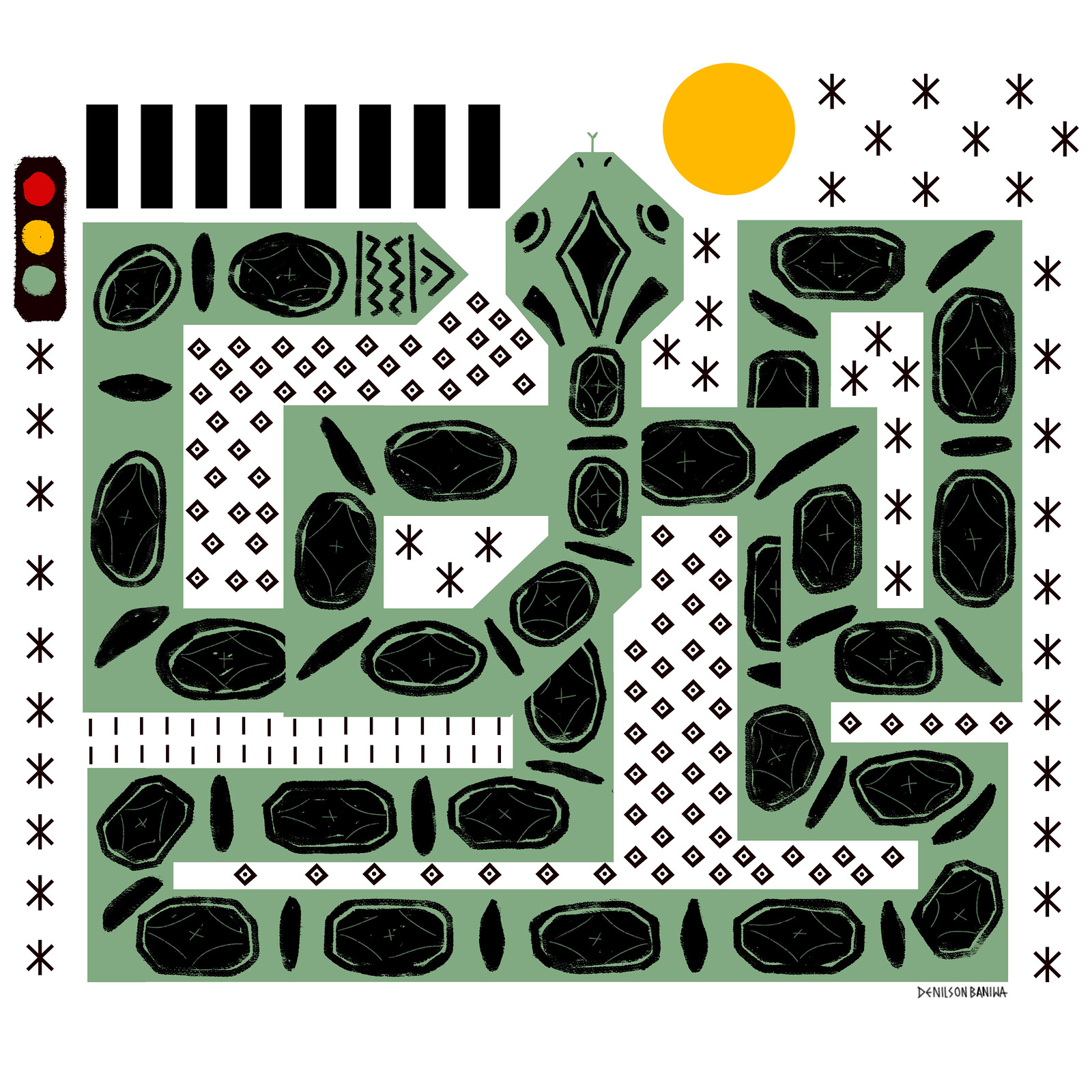

Joseca Yanomami, prompted by Cláudia Andujar, who gave him pencils and colored pens, drew these supports of the sky to show how this idea takes shape.19 You look, start thinking of the greatest contemporary artists: How is it that this Yanomami, who has never picked up a pen, makes a drawing like this? When Claudia saw the drawings, she felt completely fulfilled, because she discovered that now, among the Yanomami, there was a language that could dialogue with her photographs. She had been photographing the Yanomami and perceived that the language of photography did not make sense to them.

After that, she begins to dialogue with Yanomami thinking about the world, which is a complete transformation in the appearance of things. A tree or a piece of wood, for example: Joseca draws a suspended shape, resembling a spider web, with glowing things and antennas coming out of it, and tells you that this is, in fact, the forest. “But where are the roots, the ground?” There are none, the forest is in space. The Yanomami can perfectly imagine a forest floating in space. Because, for them, the forest is an organism, it does not come from earth, it is not the product of another event. The forest is an event itself. And if it comes to an end on the earth that we people know, it will still exist in another place. In a way, for the Yanomami, everything that exists in this world also exists in another place.

The Guarani also think like this. For them, this planet is a mirror, an imperfect world. Life is a journey heading toward a place called Yvy marã e’ỹ, which the Jesuits translated as “land without evils.” The idea of “land without evils,” of the promised land, is altered from the Christian idea, because in the Guarani worldview there was never a world that had been promised to someone. Yvy marã e’ỹ is a place after, a place that comes after the other one. A place that is nevertheless the image of this one, is nevertheless the mirror of a place to follow. The Guarani pajés (shamans) say that we live in an imperfect world, and because of this, our humanity is also imperfect. Living is the rite of crossing this imperfect earth, moved by a poetics of a place that is the mirror image of this one. And if we were to imagine the nhandere—the path that, leaving from that which is imperfect, seeks to come close to that which is not imperfect—a series of events will occur that, as the journey goes on, will bring an end to this image here and create another.

If you were to ask a Guarani, “Does this place you are heading exist?” They would say, “No.” “And this place in which you are?” They would respond, “It is imperfect.” “Okay, but you are escaping from an imperfect place and running to a place that does not yet exist?” They will say, “Yes, because it will only exist when this one here comes to an end.” I find this wonderful! And mainly, I find the exercise of thinking this way to be wonderful.

In Yanomami cosmology, the xapiri are auxiliary spirits of the shaman. They can be a hummingbird, a tapir, a jaguar, a monkey, a flower, a plant, a liana vine—all of them are people and they interact with the shaman. These beings make exchanges, alliances, they invent and cross worlds; and, while they are in movement, they move everything around them.

A shaman once told me this story:

Omama, the demiurge of the Yanomami, has a nephew who is the son-in-law of the sun. In that moment, I thought: “So the Yanomami have kin with the sun? Someone who is married to a person from the sun’s family? I need to stay calm to understand if this sun he is talking about is the star up above, if it is the actual sun.” Calmly, I went exploring this topic until he confirmed that it was the same sun.

I found this story wonderful because it shows that, for the Yanomami, there are beings that can negotiate with other entities, other existences, other cosmologies.

A shaman left this galaxy and went to another, completely unglued from ours. He tried to come back and could not: he fell into a kind of wormhole. He was sending messages, asking for help from the other shamans and from his pajé friends. He said that he had gotten lost and could not find the coordinates home.

It was a tremendous job for the shamans to bring him back. They succeeded, but he arrived defective. He spent the rest of his life sitting in the yard, sitting in the canoe. They had to place him in the sun, take him out of the sun. People would start talking, and he’d be there among them, silent, arranging little sticks on the ground.

It’s quite dangerous to enter a swerve like this, isn’t it?

Brazil’s congress is made up of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.—Trans.

A video of this action, an excerpt from the film Índio Cidadão?, is available here: →.—Trans.

Davi Kopenawa, with Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (Harvard University Press, 2013).—Ed.

Sérgio Buarque de Hollanda, Roots of Brazil, trans. G. Harvey Summ (University of Notre Dame Press, 2012).—Trans.

Quoted in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Inconstancy of the Indian Soul: The Encounter of Catholics and Cannibals in 16th-Century Brazil (University of Chicago Press, 2011).—Ed.

Quoted in Pedro Neves Marques, “Introduction: The Forest and the School,” in The Forest and the School: Where to Sit at the Dinner Table? ed. Pedro Neves Marques (Archive Books and Academy of Arts of the World, 2014–15), 27.—Ed.

“It refers to the conception, common to many peoples of the continent, ‘according to which the universe is inhabited by different sorts of persons, human and nonhuman, which apprehend reality from distinct points of view.’” Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native (University of Chicago Press, 2015), 229–30. Quotation also found in de Castro, “Perspectivism and Multinaturalism in Indigenous America,” in The Inconstancy of the Indian Soul.

The reply of Ts’ial-la-kum—who became known as Chief Seattle—to a proposal made in 1854 by the president of the United States, Franklin Pierce, to acquire the lands of the Suquamish and Duwamish Indians, in the present state of Washington, in the far northwestern US. The first version of the famous document—a transcription of the declaration of Ts’ial-la-kum, made by his friend, Dr. Henry Smith—was published in the newspaper Seattle Sunday Star, in 1887.

See →.—Ed.

The Mariana and Brumadinho dams collapsed in 2015 and 2019, respectively. Both dams were made of iron ore rejects, a useless byproduct of mining, and owned by VALE, a Brazilian mining company, one of the biggest companies in the industry. Together, the two accidents killed more than three hundred people and left a trail of environmental destruction that will be around for generations. Here, Ailton refers to the gold prospectors and miners metaphorically, to say that exploiting the land for valuable minerals has always been in conflict with the Amerindian way of life and their rights over the land they have always inhabited, particularly the Krenak people’s way of life in the Doce River basin. The collapse of the Mariana dam is particularly central to the culture of the Krenak people and their recent history, because it deeply affected the whole Doce River valley—the river that, historically, provided their means of living. The Krenak people call the Doce River their grandfather—and now, a dying grandfather.—Ed.

“Botocudos” was a generic denomination the Portuguese colonizers gave to different indigenous groups belonging to the Macro-Jê language stock (a non-Tupi group), of diverse linguistic affiliations and geographic regions, the majority of whom wore botoques, labial and ear piercings. Here, Ailton refers to the indigenous peoples who lived in the region of the Doce River valley, in the present-day states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, considered ancestors of the Krenak people.

“You must consider begun an offensive war against these cannibalistic Indians that you will continue in the dry seasons every year and that will have no end, except when you have the joy of taking possession of their homes and persuading them with the superiority of my royal weapons in such a way that, moved by their rightful terror, they ask for peace, and submitting to the sweet yoke of the Laws and promising to live in society, may become useful vassals, as are the numerous varieties of Indians that, in these, my vast states of Brazil, are villagers and enjoy the happiness that is a necessary consequence of the social state … May all Botocudo Indians who present themselves with their weapons in any attack be considered prisoners of war; and may they be handed over to the service of the respective Commander for ten years, and as long as their ferocity lasts, and they can use them in their private service during that time and keep them with due security, even in iron chains, until they prove they have abandoned their cannibalism and atrocity … and you will inform me, via the Secretary of State for War and Foreign Affairs, of everything that will have happened and that concerns this objective, so that the reduction of the civilization of the Botocudo Indians succeeds, if possible, and of the other races of Indians that I highly recommend to you.” Excerpt from the Carta Régia (Royal Letter) of May 13, 1808 that “mandates making war against the Botocudo Indians.” See →.

More than a century and a half later, the Brazilian state again takes advantage of native peoples to compose its military-repressive apparatus. The Indigenous Rural Guard (GRIN) was created by governmental regulation 231/69, on September 25, 1969, during the Brazilian military-civil dictatorship. It is made up of youth of various indigenous ethnicities, recruited directly in their villages, “with the mission of executing the ostensive policing of Indian reservations.”

The National Constituent Assembly of 1988. Formed by deputies and senators of the Republic, and installed in the National Congress in February of the previous year, it was charged with elaborating a new democratic constitution for Brazil, after the end of the military-civil dictatorship of 1964–85.

Jair Bolsonaro, president of Brazil, referring to the environmental reports of FUNAI—the National Indian Foundation, a government body—which are necessary to the licensing of certain construction projects. This declaration was made on August 12, 2019, during the inauguration of a second lane of highway BR-116, in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul.

Indigenous land located in the northeast of the state of Roraima, in the region of the borders with Venezuela and Guyana, destined for permanent possession by the indigenous groups Ingaricó, Macuxi, Patamona, Taurepangue, and Uapixana.

In the early hours of April 20, 1997, five youth from the upper class of Brasilia set fire to the indigenous leader Galdino Jesus dos Santos, of the Pataxó-hã-hã-hãe ethnicity. Galdino had come to Brasilia the previous day to discuss questions related to the demarcation of indigenous lands in the south of the state of Bahia, where the Pataxó live. Prevented from entering the boarding house in which he was staying, because of the time, Galdino slept in a bus shelter on South W3 Avenue.

Takrukkrak, meaning “Tall Rock” in the Borún language, is a mountain on the right bank of the Doce River, in the present-day town of Conselheiro Pena, in Minas Gerais, a region occupied ancestrally by the Krenak.

Joseca Yanomami is a contemporary artist, and Cláudia Andujar is a photographer.—Trans.

Category

Subject

Translated from the Portuguese by Hilary Kaplan.