“Energy is eternal delight.”

—William Blake

This essay is short and inconsistent. It grew out of a talk I gave at the e-flux conference “Art After Culture” in June 2019. When I was invited to speak, the subject I proposed was: “Desire, Pleasure, Evolution.” I will begin with a few things about those topics, but will move on to other things, namely senility and evolution.

So, desire and pleasure. I recently discovered that somewhere—I don’t remember exactly where—Gilles Deleuze recounts the story of an exchange between himself and Michel Foucault. Before leaving the house of Deleuze, Foucault kindly and shyly, in his style, tells Deleuze: you know, I must confess to you that the word “desire” disgusts me. I would prefer to use the word “pleasure,” would you agree?

Deleuze does not agree at all. He absolutely disdains the word “pleasure.” Actually, in a lecture he delivered in Vincennes in 1973, Deleuze said something along the lines of: Plaisir, quel horrible et atroce mot. Qu’est-ce que ça signifie? Le décharge? (Pleasure, what a horrible, atrocious word. What does it mean? Discharge?)

This discussion between the two is revealing of a dimension of desire as discussed by Deleuze and Félix Guattari that has always escaped me. During my years in Paris in the late ’70s, I first came to realize that desire is the engine that mobilizes social energies, but I did not consider at all the distinction between desire and pleasure. It wasn’t until just last year that I understood the difference, while reading about that exchange between Deleuze and Foucault.

Of course, one can find an explication of the difference in Jean Baudrillard, the real wise man of the Parisian scene of the ’70s and ’80s. Baudrillard says: desire, yes okay, the desire for beautiful things, but beware that the entire history of capitalism is based on permanent desire.

Now, in my old age I have come to (painfully) appreciate the difference between desire and pleasure, and I understand that capitalism is, in fact, based on an endless postponement of pleasure, and simultaneously on the permanent excitement of desire. Virtual capitalism—what I call semiocapitalism—is an intensification of both these conditions, postponing pleasure and exciting desire.

Another catalyst for my realization of how they differ is feeling physically, personally that growing old essentially means losing the ability to access certain spheres of pleasure, while desire continues undisturbed. Beyond my personal experience, and its suggestion of a larger condition, there is something more interesting, and more disturbing, in the relationship between the two. This relationship—between the permanent burning of desire and the inaccessibility, the unattainability of pleasure—has something to do with the present historical moment of transition, the present step in human evolution.

Why are older people so nervous? Cantankerous even? I don’t even know the meaning of this word, but it sounds right. Why are old people so malignant?

I have two answers. The first has to do with the disappearance of neurons and synapses in old age: the reduction in the ability to process information, the loss of subtlety, the loss of definition in the relationship between sensibility and experience. The second is that we—we humans, old humans in particular—tend to cling to life because we think it is our private property. This life is mine, and I don’t want to lose this property.

The denial of death is deeply inscribed in the modern mind. As the world’s white population grows old, this has provoked something resembling a social psychosis, an aggressive grasping among the old for all that is left: naked life, putrescent life.

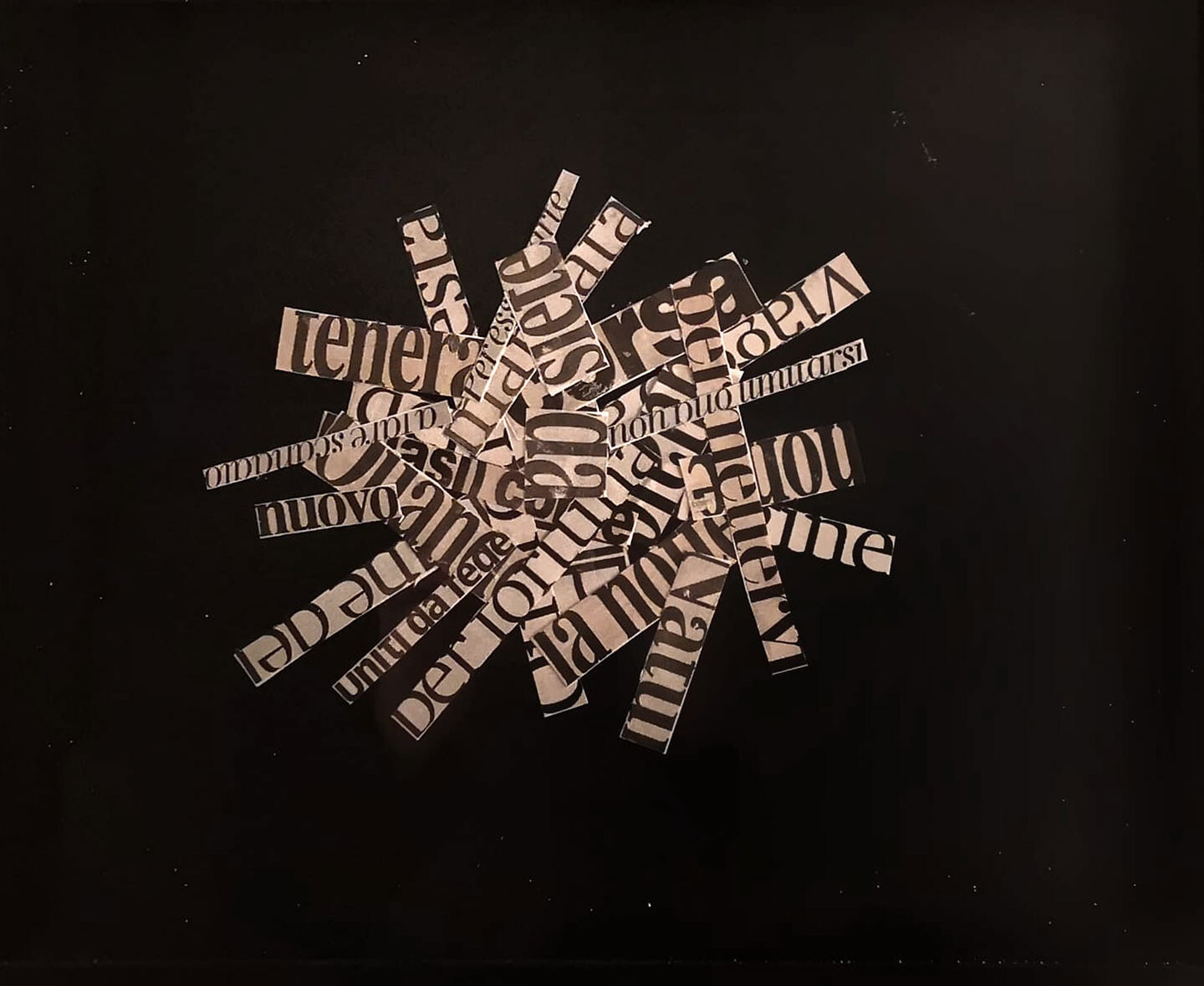

Nanni Balestrini, Tristanoil, 2012. Courtesy of Galleria Michela Rizzo and Eredi Nanni Balestrini.

At the end of his beautiful book The Order of Time, Carlo Rovelli writes that the fear of death is a mistake of evolution. It is an error provoked by the inability to think the world without one’s own presence within it, an inability to think the world without me. Modern culture emphasizes the individual in continuous competition with other individuals, and consequently erases a sense of community among people. Thus, it has turned death into something that cannot be thought, said, or psychically elaborated. Death is systematically denied, which in turn leaves the individual alone in an infinite desert of sadness, and ultimately unable to see the continuity among the individual and the community, among me and you.

Furthermore, modern capitalism is based on an idolatry of energy. It is based on an obsession with growth, expansion, productivity, acceleration—futurist obsessions that have made senility unthinkable.

Why am I writing about these strange and slightly scary subjects? Why am I talking about senility and death? Of course, the main reason is that they are my problems. But, believe me, they’re not my problems alone. They are two of the main problems of humankind in the present. The denial of death, linked to the idolatry of energy and expansion, has turned decline and un-growth into purely negative tendencies, and frugality into scarcity. So, in this sense, life has become a paranoid fight against the passage of time.

I strongly believe that senescence is the (unseen or unfathomed) key to understanding the present historical conundrum, just as decline is simultaneously the problem and the solution to the late-modern crisis.

Firstly, we can surmise that this situation is due to demographic reasons. Senility now tends to be the condition of most of the Western population, and not only of the Western population. While the African population grows exponentially, while the populations in the Middle East and on the Indian subcontinent steadily grow, Western dominators and aggressors are ageing, they are losing energy, and most of all, they are losing the innocent faith in the future that belongs mostly to younger people.

The demographic gap between the population explosion in much of the South and the decline in the North is probably one of the central reasons for contemporary racism and aggressiveness. Old people have transferred their declining potency to the machines, and the war machine is in motion as a permanent menace against those oppressed in the South, the colonized people who try to migrate towards the declining Northern lands. This is why we must consider the crucial problem of senility if we want to understand anything at all about what is happening in the social, cultural, and political spheres.

Let’s think about the worldwide resurgence of “fascism.” Donald Trump, Matteo Salvini, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage, Vladimir Putin, and Recep Erdoğan. Are they fascists? No, they are not. And the process that is expanding in large parts of the world, is this fascism? No, it is not.

Fascism was a historic phenomenon comprised of young people. It was a movement based on the will-to-power of a strong, energetic, futuristic movement. It involved people who expected a bright future, and promoted expansion, the colonization of territories and markets. Nobody expects a bright future nowadays. And expansion is no longer possible because the entire planet is subjugated, while markets are saturated. The colonization of territorial spaces is over—only time can be colonized nowadays. The only direction for expansion today is the intensification of time and the acceleration of mental rhythms. Only the virtual expansion of cognitive space and the accelerated circulation of signs is possible. But this kind of intensification is blowing up the nervous systems of humankind.

Forty years ago, I remember shouting, “No future! No future!” with some young British musicians. I thought it was the provocation of a unlikely avant-garde. Now, everybody thinks that the future is over; now, the sentiment aligns with a conformist position held by most of humankind. “No future” has become common sense, and this is why cynicism is expanding in contemporary culture, in contemporary political behavior. Futurism was the expression of a society that expected something from the future, and of a society that truly felt the warmth of community, whether encapsulated in the nation, the family, or social ties to working communities. All the above was the reality of lived experience a hundred years ago. No more! Today, the nation is a nonexistent thing. The dissolution of the nation is an effect of the pervasive digitalization of information and of power based on information. Do you think that Google belongs to the United States? Not at all. The United States belongs to the territory of Google. So does Italy, and France, and so on.

National sovereignty has been dissolved by the virtual ubiquity of power; the nation has come back as a myth, as an aggressive form of identification, as nostalgic rage.

Belonging has been transformed into a hopeless nostalgia that is at the root of contemporary supremacism. Supremacism is an expression of older people’s fears. For example, it is because they fear migration that they view it as an invasion.

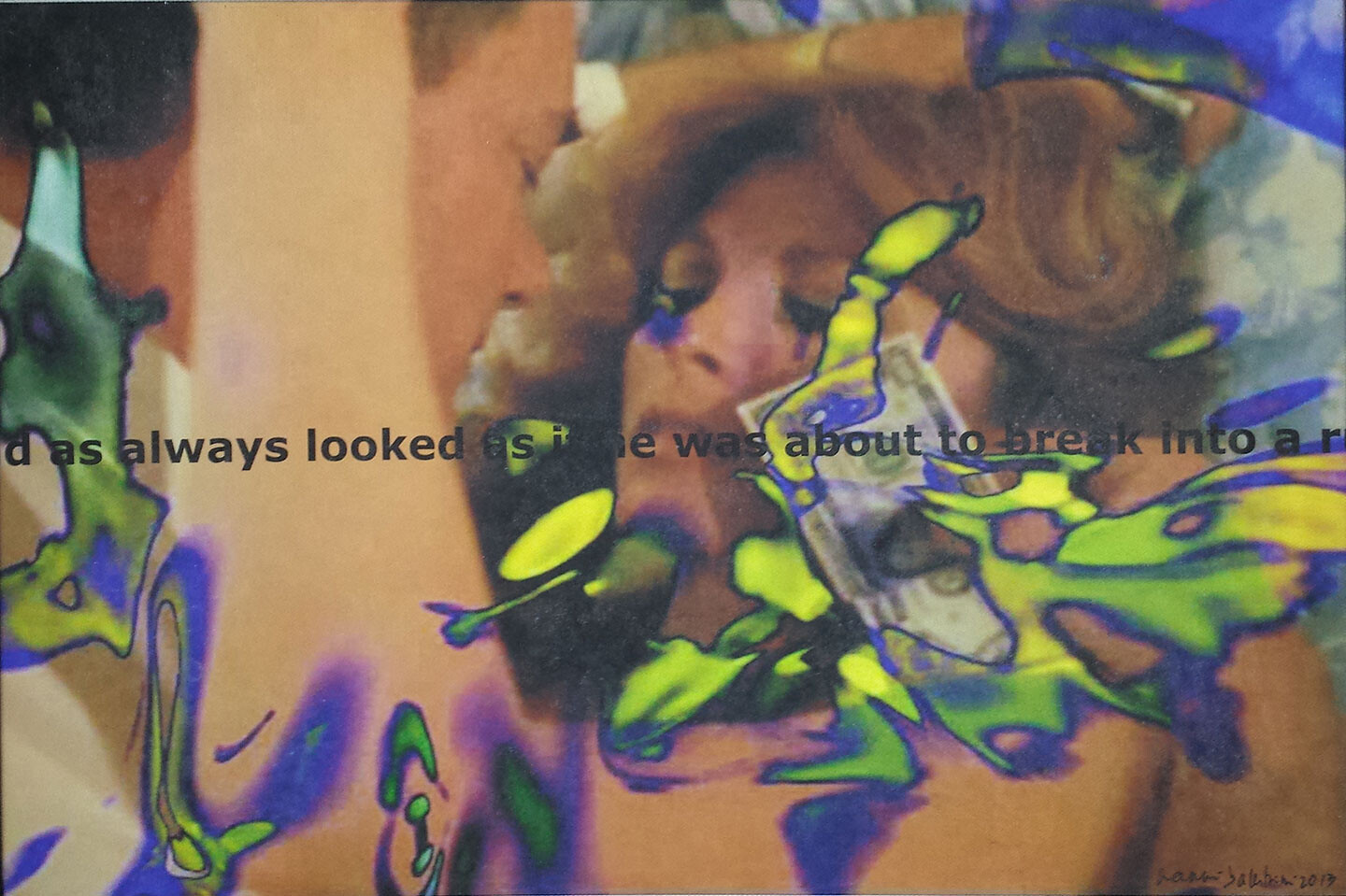

Nanni Balestrini, PLIS—Kaiser n7, 1989. Courtesy of Galleria Michela Rizzo and Eredi Nanni Balestrini.

And, largely, it is an invasion. One or two hundred years ago, racism was an integral part of the invasion by white people of the Southern territories of the world. Nowadays, racism is the fearful reaction by white people to the perceived invasion of their own territories. And the racist paranoia of the great racial “substitution” is not merely a phantom, because it corresponds to a real process (one that is happening without the aid of a conspiracy involving George Soros). The white race is—thank god—disappearing. This is the root of contemporary supremacism, which is simultaneously impotent and hyper-powerful; it is unable to change a future of certain decline, but at the same time it is perfectly able to destroy the world in desperate acts that aim to reassert a potency that has vanished.

“Impotence” is the word that explains what is happening, particularly in the Northern parts of the planet. Impotence and the desire for revenge. The neoliberal left has destroyed any possible expectation of a political transformation for the future. The neoliberal left: the Clintons, the Blaires, the D’Alemas, François Hollande, and so on. These traitors have destroyed any possibility of expecting something meaningful from politics and from reason. Reason, for its part, has become the servant of financial algorithms. When reason is the financial algorithm, the only thing that we can expect from the future is revenge—indeed, a revenge against reason. Horkheimer and Adorno speak of this revenge against reason in the preface to The Dialectic of Enlightenment. They write that if reason is unable to grasp its dark side, the unconscious dark side of reason itself, then reason ensures its damnation. It is dead. Revenge against reason is the driving force of the neoreactionary movement that is spreading: it is revenge against humanity itself.

Humanity as a cultural horizon has become the main enemy of the contemporary fascists who are not fascists. They are simply antihuman. That would be a kind definition for Matteo Salvini, for a guy who has built his fortune on his declared determination to kill people who come to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea. But remember that Salvini, the right-wing killer, a murderer in the Italian government, is only continuing the political attitudes and applying the rules written by Marco Minniti, the former leftist minister of the interior, who before Salvini passed laws that criminalized nongovernmental organizations that rescue people at sea. Salvini is the direct continuation of a democratic murderer named Marco Minniti. Therefore, it is clear that a political way out of this situation does not exist.

Where do we go from here?

I recently read Staying with the Trouble by Donna Haraway. When I read Haraway, I don’t understand everything, but I understand the essentials. She says, in an ironic and beautiful way, that today there are two reactions to technology. On one side, there are the techno-optimists, who believe that technology will save humanity, the planet, and the environment. On the other side are the techno-apocalyptics, who say no way, technology will destroy everything. Haraway takes a different stance: she instead tells us to keep calm. She says that it isn’t a tragedy that the human race is doomed to disappear.

Extinction is the new buzzword on the political scene nowadays. Look at the enormous demonstrations organized by children in Sweden, in Germany, in Italy, everywhere in the world. Millions of children marched on March 15, 2019. Their message is about extinction. They don’t have a political problem. They simply say: it’s time to panic. And look at Extinction Rebellion. It’s the first time in human history, as far as I know, that extinction has become the core concern of a political protest movement.

I would not focus on rebelling against extinction. Can one even rebel against extinction? I don’t think so. You can deal with extinction. You have to deal with extinction. Extinction, by the way, is not the worst thing that one can imagine for the future. The worst thing imaginable is the war that will lead to extinction—not death, but the long-lasting agony that financial capitalism has prepared for humankind. This is the real danger. Extinction is not so bad, if we compare it to capitalism.

After quoting Haraway, I want to quote the French philosopher and psychoanalyst Catherine Malabou. She says that psychoanalysis has undergone a shift from the analysis of sex and language to neurology. The fields of sex and language have long been the focus of psychoanalytic theory and therapy. But when we speak of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, or of panic attacks and depression, we can see that they’re not just problems related to sex and language. They concern the physical dimensions of neurology. It’s neurology nowadays that is at stake. It’s the brain, not the mind. Or better yet: not only the mind, but also the brain. Malabou, taking up this thread, writes of trauma and neuroplasticity.

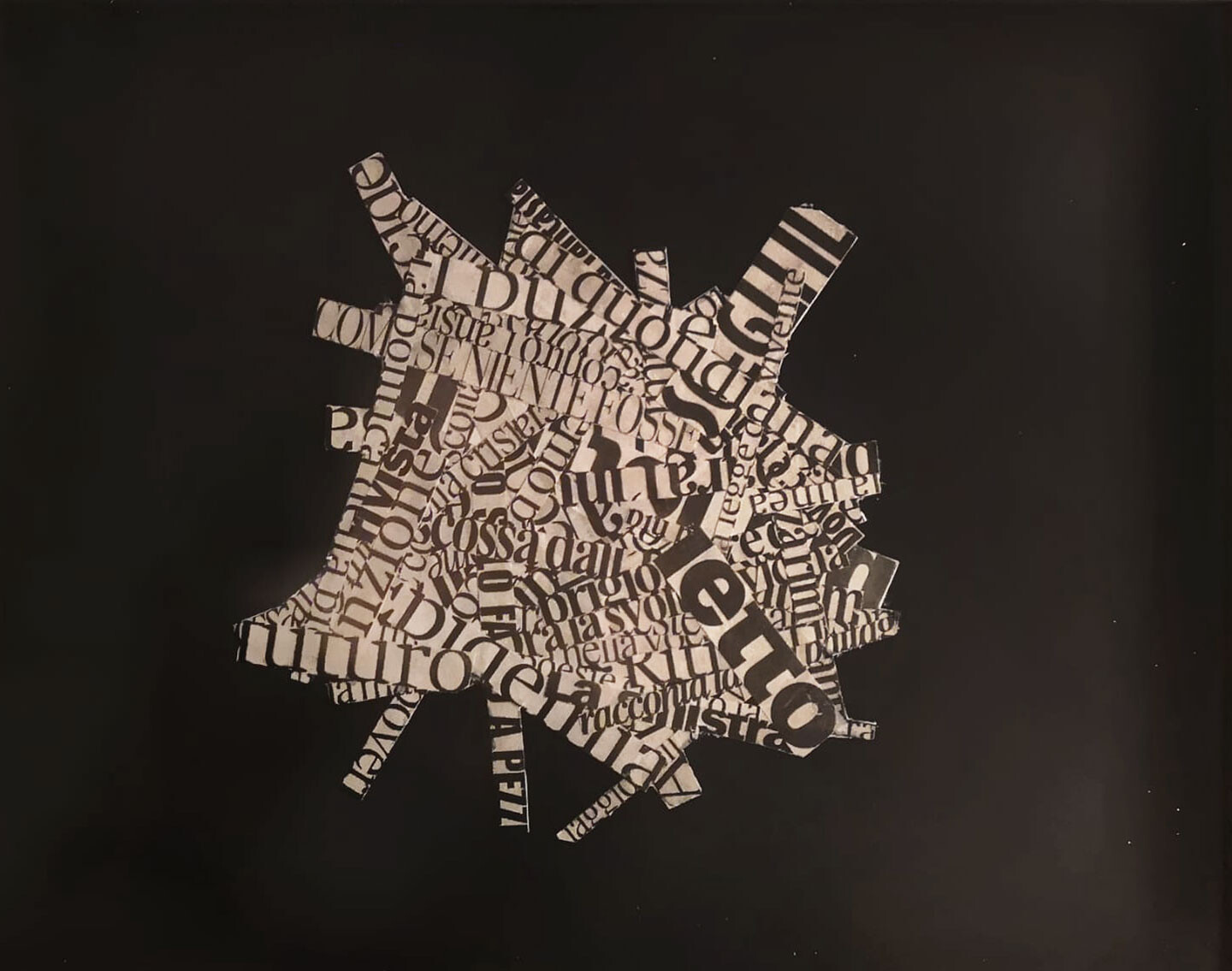

Nanni Balestrini, Come Se Niente Fosse, 1960. Collage on paper. Courtesy of Galleria Michela Rizzo and Eredi Nanni Balestrini.

Evolution must be rethought from scratch, from the point of view of the relationship between desire and pleasure. Pleasure is the goal, the aspiration. Over the past forty years, I forgot about pleasure because I was obsessed with desire, but now I understand that the way out of capitalism is the opposite: the way out is not desire, it is pleasure. And how can the brain find a new balance of pleasure in the present? This is the problem that we are going to face in the coming years, in the coming decade.

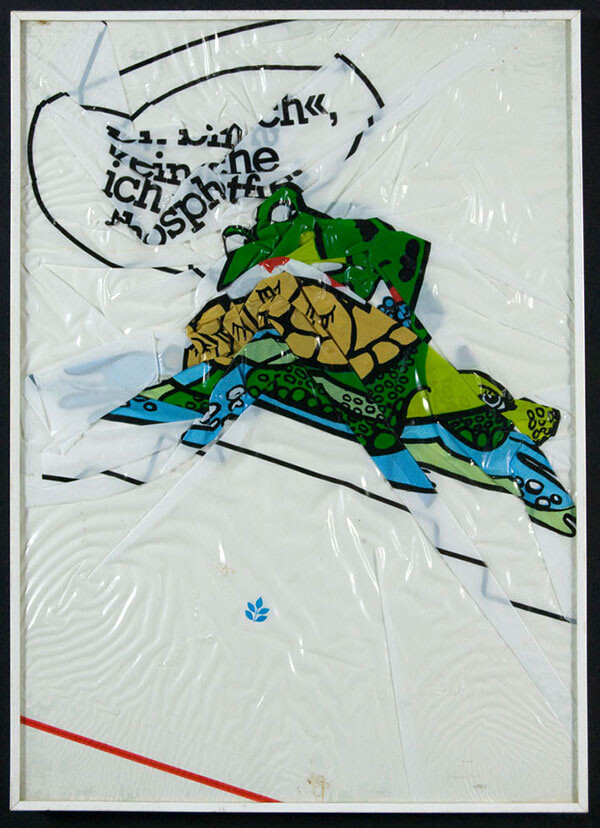

I want to dedicate this inconsistent essay to a friend who died in May 2019. The name of this friend is Nanni Balestrini. Nanni was a poet, a novelist, and most of all a recombiner. He is the first poet in history of humankind who never wrote a single word. He refused the dirty work of writing words. He asked: Why should I do that? Why should I spend my time writing words? I’m a poet. I don’t write words. I take signs from the infosphere, from the daily conversations of people in the subway, from newspapers, from advertisements. His activity, he said, was to recombine. Recombination is also our task, and we should take a cue from him. But the question is: the recombination of what? The recombination of meaning, of language, of desire, of pleasure. Poetry is the consistent and intentional recombination of what exists, with the aim of creating what does not yet exist.