Imagine Going on Strike: Museum Workers

In contrast to liberal and social democratic arguments, Alex Gourevitch proposes a radical view of the right to strike. The right to strike, he claims, is derived from the right to resist oppression. In the case of strikes, he argues, oppression “is partly a product of the legal protection of basic economic liberties, which explains why the right to strike has priority over these liberties.”1 However, conceiving of a strike as the last but not the least right of the oppressed against their oppressors doesn’t exhaust the potential of the right to strike. Alongside this radical conception of strike, and by no means as its replacement, I propose to consider the strike not in terms of the right to protest against oppression, but rather as an opportunity to care for the shared world, including through questioning one’s privileges, withdrawing from them, and using them. For that purpose, one’s professional work in each and every domain—even in domains as varied as art, architecture, or medicine—cannot be conceived for itself and unfolded as a progressive history, nor as a distinct productive activity to be assessed by its outcomes, but rather as a worldly activity, a mode of engaging with the world that seeks to impact it while being ready to be impacted in return.

In other words, if one’s work is conceived as a form of being-in-the-world, work stoppage cannot be conceived only in terms of the goals of the protest. One should consider the strike a modality of being in the world that takes place precisely by way of renunciation and avoidance, when one’s work is perceived as harming the shared world and the condition of sharing it. In a world conditioned by imperial power, a collective strike is an opportunity to unlearn imperialism with and among others even though it has been naturalized into one’s professional life. Going on strike is to claim one’s right not to engage with destructive practices, not to be an oppressor and perpetrator, not to act according to norms and protocols whose goals were defined to reproduce imperial and racial capitalist structures.

To strike in this context is to consider one’s expertise-related privileges, which are at the same time part of one’s skills, and use them to generate a collective disruption of existing systems of knowledge and action that are predicated on the triple imperial principle. Imagine artists, photographers, curators, art scholars, newspaper editors, museumgoers, or art connoisseurs going on strike and refusing to pursue their work because the field of art sustains the imperial condition and participates in its reproduction. An analogy may be helpful here. Think about the group of programmers who went on strike and refused to build the technical platform for US immigration services. Being aware that IBM workers have been implicated in assisting the Nazi regime, they opt to avoid finding themselves, simply by doing their job, complicit with similar mechanisms that inflict harm and destroy the shared world.2

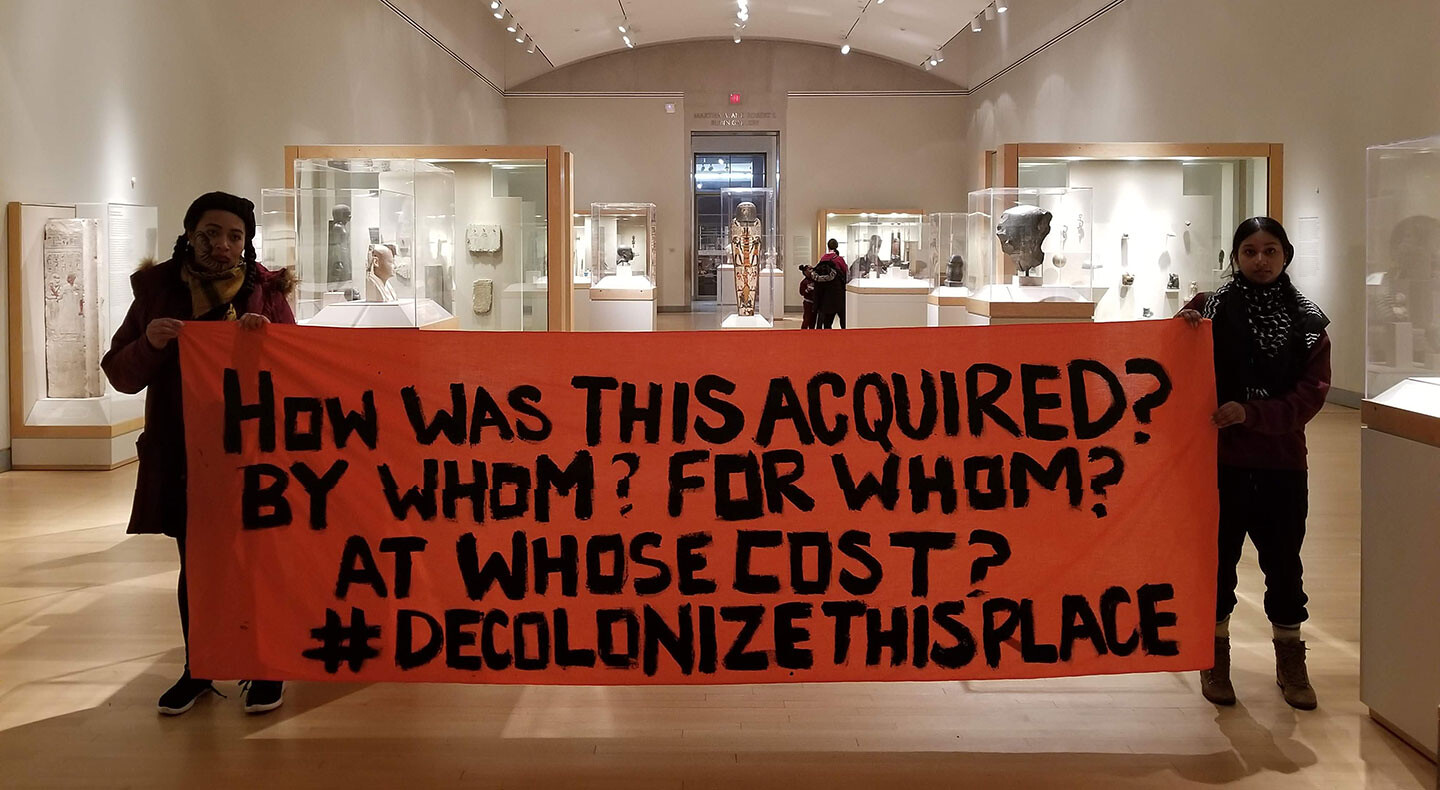

Courtesy of Decolonize This Place.

Imagine a thousand museumgoers who on Indigenous People’s Day go on strike and withhold the recognition that they are expected to give the museum exhibits; imagine them screaming that these exhibits are proof of imperial crimes, of genocides, human trafficking, and trade in organs, that these are denigrating statements or racist slurs. This doesn’t require an analogy or imagination—this is the strike museumgoers are performing, organized under the loose activist affinity of Decolonize This Place. Imagine the same, but performed not only by museumgoers but also by museum experts.

Imagine. It is not unheard of. On the contrary, professionals in the world of art have been on strike and use their working power to put pressure on the employing institutions or exercise it as “productive withdrawals,” to use Kuba Szreder’s term.3 We know little about strikes. We often do know that they did take place, that some of them, mainly those that involved salary demands and working conditions, led to some reforms, and that hardly any of them had an effect on the imperial condition under which the world of art operates. Trying, however, to assemble the pieces, to connect processes of impoverishment, dispossession, exploitation, and the enslavement of people with the destruction of material worlds, looting and denigration of world-building qualities, one finds that the history of anti-imperial strikes within the art world has already been potentialized. Numerous strikes in colonized Africa against tax collectors or companies that hunted workers should be recognized as strikes against the institutionalization of the abyss between people and objects, against the imperial powers that forced people to turn their world-building skills into cheap or slave labor, and their sacred, spiritual, and ecological objects into commodities. Imagine a strike not only against this or that museum but against the very logic of the capital embodied in museums in its ultimate overt deception.

Imagine a strike not as an attempt to improve one’s salary alone but rather as a strike against the very raison d’être of these institutions. Imagine a strike not out of despair, but as a moment of grace in which a potential history is all of a sudden perceptible, a potential history of a shared world that is not organized by imperial and racial capitalist principles. Imagine the looted objects as the palimpsests in which these potentialities are inscribed.

Imagine experts in the world of art admitting that the entire project of artistic salvation to which they pledged allegiance is insane and that it could not have existed without exercising various forms of violence, attributing spectacular prices to pieces that should not have been acquired in the first place.4 Imagine that all those experts recognize that the knowledge and skills to create objects the museum violently rendered rare and valuable are not extinct. For these objects to preserve their market value, those people who inherited the knowledge and skills to continue to create them had to be denied the time and conditions to engage in building their world. Imagine museum directors and chief curators taken by a belated awakening—similar to the one that is sometimes experienced by soldiers—on the meaning of the violence they exercise under the guise of the benign and admitting the extent to which their profession is constitutive of differential violence. Imagine them no longer recognizing the exceptional value of looted objects, thus leading to the depreciation of their value in the market and the collapse of the accumulated capital. Imagine these experts going on strike until they are allowed to open the doors of their institutions to asylum seekers from the places from which their institutions hold objects, inviting them to produce objects similar to the looted ones, and letting the “authentic” ones fade among them.

Dare to imagine museum workers going on strike until they are allowed to invite an entire community of “undocumented people,” not to attend the opening of exhibitions of objects extracted from their communities, but to stay for a period of several years to help the museum make sense of its collections of objects from their cultures. Imagine the museum workers letting them lead the conversations around what should be done with the looted objects and the destroyed worlds from which they were extracted. Imagine museum workers invested in interpreting the infographics showing asylum seekers from the same countries as the museal objects’ provenance and understanding asylum-seeking as a counterexpedition by people in search of their objects and destroyed worlds. Imagine them admitting that they were trained to believe themselves to have been acting on behalf of the public, but that in fact that public was a very specific one, exclusive and hierarchical, and their commitment actually catered to the interests of imperial actors, including museum directors, boards of trustees, gallery owners, collectors, dealers, statesmen, and corporate stakeholders. All these interested actors tied their hands and prevented them from engaging with their museum’s debts (its real debt, not the debt incurred due to budgetary deficit) to those people whose worlds were destroyed so that the museum and its stakeholders could be enriched. A proof of the museal and art experts’ service to the imperial actors, if a proof is still needed, can be found in the piles of papers through which the traffic of looted objects has been cleansed so that precious artifacts could be stored in the museum, and particularly in the papers through which donations have been described, stipulating that such objects can be resold only to other museums should the museum decide to deaccession them. Imagine a strike like this.

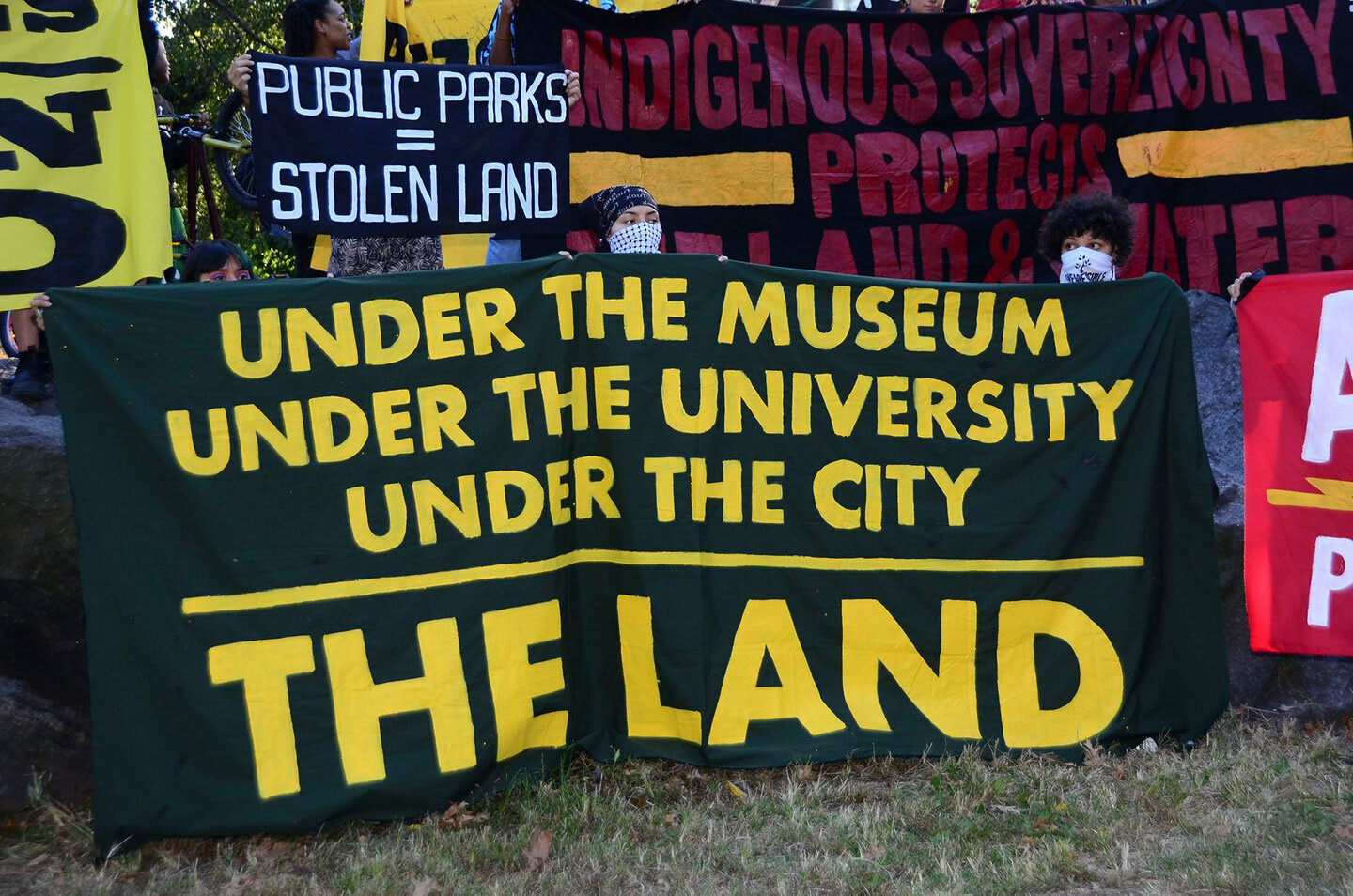

Courtesy of Decolonize This Place.

Imagine Going on Strike: Historians

What would it take for historians to go on strike, to waken into recognizing their structural complicity as members of their discipline in facilitating the violent transition of imperial actions into acknowledged realities, which colonized people have never stopped resisting? Let me clarify. Actions, as Arendt puts it, are never carried out only by those who initiate them, they are continued by others. Many of the imperial actions were continued by the actors’ armed peers, but since they were also resisted in so many ways, they have never been brought to completion—except in historical timelines and narratives. This makes historians, whose work runs on timelines and narratives, structurally complicit in imperial endeavors.

For historians to go on strike, they have to recognize themselves in Saidiya Hartman’s dread: “what it means to think historically about matters still contested in the present and about life eradicated by the protocols of intellectual disciplines.”5 As part of their training, historians were taught to believe that their responsibility consists of accounting for the significant, endurable, and lasting consequences of their protagonists’ actions, thus implicitly affirming the nothingness of others’ shredded lives. Historians should learn to recognize the imperial power that trained them to ignore or belittle what stood in the way of that violence, in the form of resistance, stubborn persistence, or sheer existence. To tell about one event, including about resistance, is to not sustain resistance as a vital force continuing into our present. Historians’ crime should not be measured by their individual books, nor can it be absolved by complementary chapters dedicated to people and groups that imperial violence sought to seal in history or experience as ghosts. It is the crime of a discipline that crafted a worldview for colonized worlds based almost solely on the actions, taxonomies, declarations, and proclamations of imperial agents.

Because they complete imperial violence by situating events on a linear timeline, historians are recognized as experts capable of crystallizing the meaning of others’ actions, honored as guardians of the sealed past. Together with other experts, they are trusted to explain the past, transform reparations claims into an esoteric object of study rather than a historical force, justify existing orders, and illuminate current events. Without historians’ service, “world history” would have never assumed the mantle of a broad-minded, scholarly pursuit full of cosmopolitan subjects, and the crimes on which “world history” rests would not have been denied, ignored, or presented as accomplished facts. The invention of world history is predicated on a set of premises that enable, encourage, authorize, and justify the imperial penetration into other cultures and the conversion of their modes of life, cultural and religious practices, habits and beliefs to temporal, spatial, and political categories foreign and harmful to their world.

Through maintaining the facticity of archives and timelines, professional historians are guilty of sanctioning the disappearance of people in a way that their lasting presence can only be perceived and theorized as a ghostly haunting or a partial afterlife, not the continuing presence of the whole and the living. Thus, for example, in their glossary of haunting, Eve Tuck and C. Ree capture settler-colonial descendants’ astonishment: “Aren’t you dead already? Didn’t you die out long ago? You can’t really be an Indian because all of the Indians are dead.”6 In a historicized world, where imperial crimes were relegated to the past, speaking about the “relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation” makes sense. However, Tuck and Ree disavow this past sustained by historians in their argument about decolonization: “Decolonization is not an exorcism of ghosts, nor is it charity, parity, balance, or forgiveness.”7 This should be spelled out: it is not exorcism and it cannot be appeased, since these are not ghosts but real people who never disappeared. They do not haunt; they exist and do not let go.

If proof is still needed for this crime, it can be found in the persistence of precolonial knowledge about invaded, stolen, and occupied lands, as an existent body of knowledge that nonetheless continues to surprise us at each emergence. This is true for the names of places, peoples, and objects as well as for knowledge of agriculture, medicine, or ecology. This diverse knowledge was protected by native peoples and transmitted to future generations, without losing its incommensurability through the imperial spatio-temporal-political foundations of the discipline of history that sought to shape them into preexisting transcendental forms.8 Going on strike until this knowledge is no longer denied would mean going on strike until imperial politics is abolished together with the kind of history used for its legitimization.

Historians are guilty of inhabiting the position of judge in the court of history, as if the struggle was over and they themselves are removed from the world. But imperial powers themselves established the court of history. Historians are guilty of translating the incommensurability between precolonial knowledges and imperial categories into theories and practices that render plausible the linear flow of time, sealing into “the past” struggles that persist in our present. Historians’ interest in and care for collecting remnants from this past are part of the same crime. They have used the “remnants” to prove the pastness of the cultures and people to which these “remnants” belong.

Imagine historians using the trust given to their profession and expertise to go on strike. Imagine the day when they would cease to provide alternative interpretations and new timelines, new ways of sealing the past. Imagine them ceasing to use their power to assert that in May 1945 a world war was ended, or that in July 4, 1776, a new democratic republic was established, or in May 5, 1948, the state of Israel was created. Imagine historians going on strike until stolen lands are called by their old names, and the Babel Tower of “world history” collapses so imperial extraction, conversion, outsourcing, and other modalities of domination can no longer be disavowed. Imagine that no alternative history is needed, and no history serves any longer as the arbiter of violence.

Imagine historians using their symbolic power, resources, and institutional positions in universities, archives, libraries, and publishing houses to go on strike, ceasing to produce further history books that offer “alternatives” to existing history, thus affirming its plausibility by being merely in need of revisions. Rather, they might use their skills to revise and repair existing books as a mode of intervening in existing narratives and assuming responsibility for what the discipline previously sustained. Imagine them equipped with artisanal tools such as tapes, photos, pens, colors, excerpts of texts, and rubber erasers, and using them to acknowledge that the incommensurable was never the past but was and always is a living force. Imagine them using their power to revoke the sacredness of books kept in libraries and opening up closed university libraries to the public. Imagine historians going on strike until street names, maps, and history books are replaced, appended, or discarded altogether.

Going on strike means no more archival work for a while, at least until existing histories are repaired. No more time should be spent in archives to look for what descendants of people who were destitute were able, against the crimes of the discipline, to protect and transmit in place of imperial documents. Historians should withdraw from being the judges (or angels) of history and instead support and endorse community-sourced knowledge. They should go on strike whenever they are asked, by their discipline and peers, to affirm what the latter should know by now, that history is and always was a form of violence. When more than one million women were raped in Germany in the spring of 1945, no war was ended; when 750,000 Palestinians were expelled from their homeland and were not allowed to return, nothing was established; when millions of African Americans were made sharecroppers, they continued to be exposed to regime-made violence; when millions from India, Africa, and China were made “indentured workers” to “solve” the “labor problem” of the plantation system, slavery was not abolished. Evermore, violence has been required to obscure the rape as lost memories to be discovered, events to be painstakingly reconstituted by scholars working in archives. To repair the violence, historians must go on strike to know that the violence still exists and that there is no such thing as the “postwar” world.

Imagine historians ceasing to relate to people they study as primary sources. Imagine them turning their discipline from one that seals destruction in the past to one that tells stories that prepare the ground for the reparation of imperial crimes. Imagine historians rewinding everything made past by their discipline and opening its discourse wide. Imagine historians going on strike, turning accepted imperial facts into criminal evidence and withholding their authority and approval from collecting and recirculating these facts. Imagine historians proclaiming imperial governments (previously thought of as accepted regimes) “null and void” since they were constituted against any body politic that they governed.

Imagine historians who understand that what sounds like a heavy charge against them is rather a charge against their discipline, which they have the power to radically change. Imagine historians who, instead of resisting the charges against their discipline, assume collective responsibility for their discipline’s corpus, timelines, facts, narratives, and publications.

For historians to go on strike means to acknowledge their discipline’s failure to see the ongoing resistance of destitute people, the stolen status of lands, the silencing of names, the repression of knowledge formations and other ways of naming and telling, and the transmission of that disavowal to further generations. We were wrong, they would say, and we will not continue to consult state and institutional archives until indigenous people and former colonized people are allowed to enter and take leading roles in decisions about the documents stored there. Ceasing to use archives until such a copresence is possible will change the status of the archival document itself. Historians should go on strike until the knowledge of the formerly colonized is allowed to undermine history as it has been practiced and work for the recovery of sustainable worlds.

Imagine historians refusing to use their expertise and knowledge until the precedents used to justify injustice are replaced with worldly and nonimperial rights, guarded and preserved by those who were destitute, beginning with the right to care for the shared world. Imagine historians striking until their work could help repair the world.

Alex Gourevitch, “A Radical Defense of the Right to Strike,” Jacobin, July 12, 2018 →.

See Anthony Cuthbertson, “Amazon Workers ‘Refuse’ to Build Tech for US Immigration, Warning Jeff Bezos of IBM’s Nazi Legacy,” Independent, June 22, 2018 →.

On strikes within the world of art, see Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (Verso, 2016); Kuba Szreder, “Productive Withdrawals: Art Strikes, Art Worlds, and Art as a Practice of Freedom,” e-flux journal no. 87 (December, 2017) →; “Alternative Economies Working Group,” Arts and Labor →; and Gulf Labor Artists Coalition →.

See the BBC film Bankers Guide to Art (2016), in which art is presented as an exceptionally stable asset, worthy of investment →.

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (2008): 9–10.

Eve Tuck and C. Ree, “Glossary of Haunting,” in Handbook of Autoethnography, eds. Stacey Holman Jones, Tony E. Adams, and Carolyn Ellis (Routledge, 2013), 643.

Tuck and Ree, “Glossary of Haunting,” 643.

This text is an excerpt from Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, published this month by Verso Books.