Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

September 6, 2024 – Review

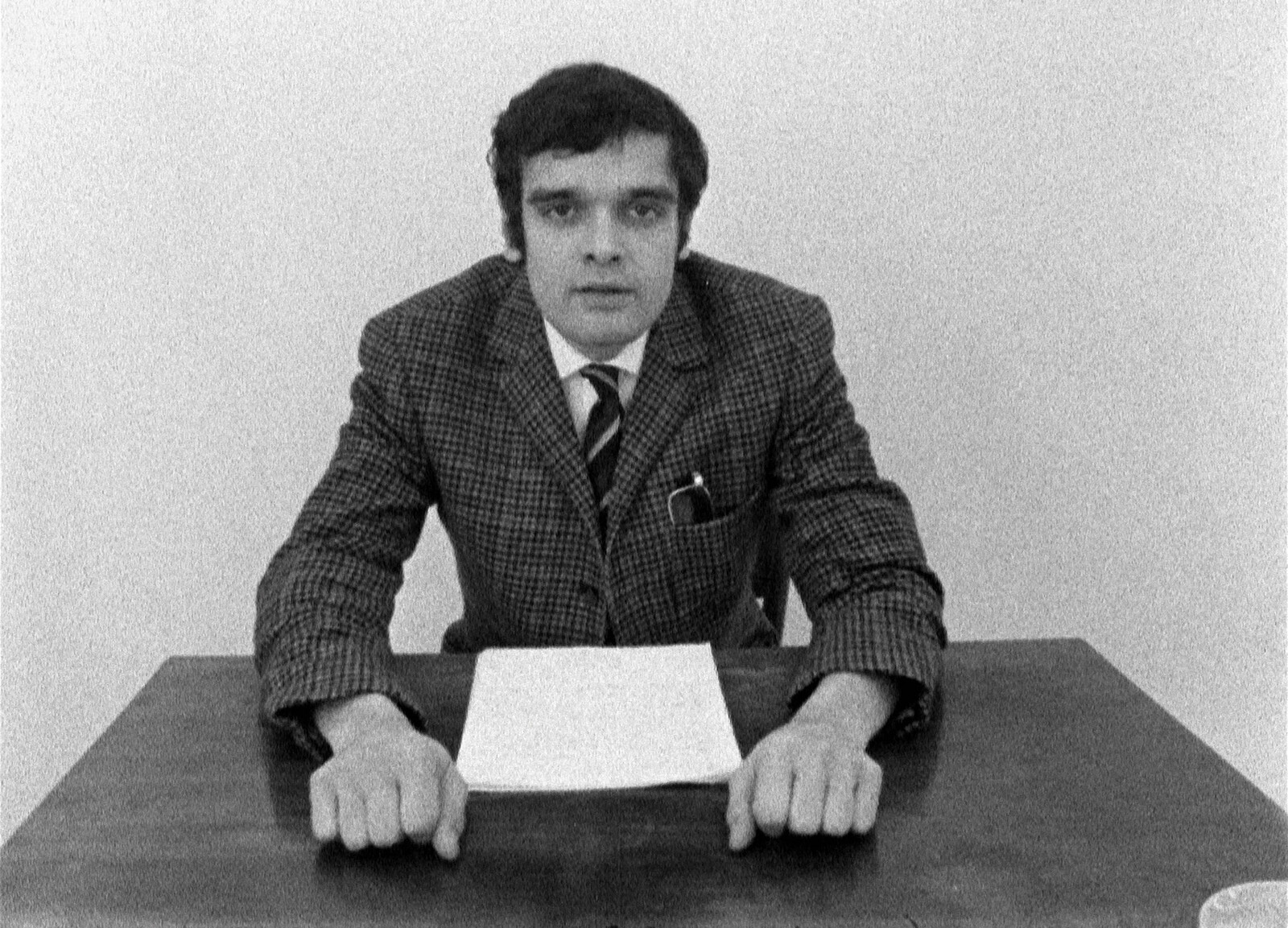

Harun Farocki’s “Inextinguishable Fire”

Leo Goldsmith

Greene Naftali’s new exhibition of works by Harun Farocki derives its title from perhaps the German filmmaker’s most famous work, a gently excoriating and laser-sharp 1969 film about the complicity shared amongst politicians, Dow Chemical executives, and ordinary workers in the production of the chemical weapon napalm. Inextinguishable Fire remains utterly devastating, a frightening but cogent delineation of the phases of dissociation we experience as we gaze at media images of atrocity, and a methodical examination of how the abstraction of labor makes us unconscious of our complicity in the violence of war.

Here, however, the specificity of Farocki’s title is, along with its definite article, lost. This lends it a more nebulous quality. Perhaps the “inextinguishable fire” in question refers not to a chemical weapon, the slightest drop of which—the film’s voiceover narration tells us—burns for half an hour at a temperature of 3,000 degrees Celsius. In the context of a show that marks a decade since the filmmaker’s death, the title almost sounds like a tone-deaf tribute to Farocki’s burning legacy. It loses its precision as a catch-all for a group of works that branches two different phases of the filmmaker’s career (the 1960s and the 2000s) and …

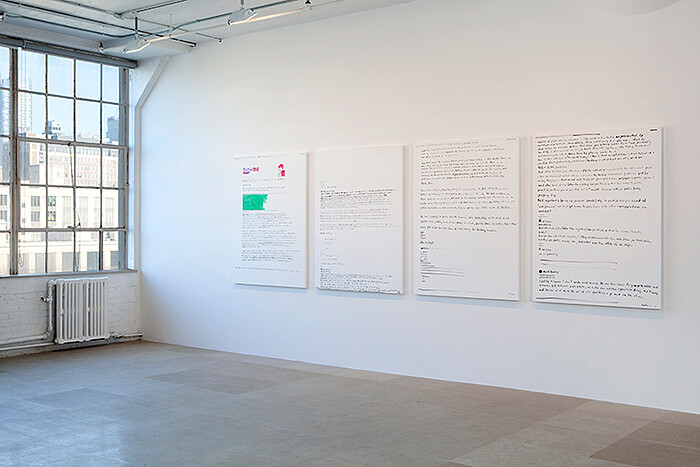

June 23, 2023 – Review

Aria Dean’s “Figuer Sucia”

Katherine C. M. Adams

One enters Aria Dean’s exhibition “Figuer Sucia” through Pink Saloon Doors (all works 2023) that open onto a vaguely neo-Western mise-en-scène. An ambiguous gray sculpture—heavily textured, with densely packed contours that evoke layers of folded skin and the crushed musculature of a horse—sits on a wooden pallet at the center of the room. This mildly cubic, contorted sculptural figure (FIGURE A, Friesian Mare) appears to be cowering, its subject’s equine body nearly unrecognizable. Dean’s recent exhibition at the Renaissance Society, “Abattoir, U.S.A.!,” took the slaughterhouse as a way to examine the limits of subjecthood. Its central film work walked the viewer through the environments of factory farming. While Abattoir, U.S.A.!’s featured architecture was outfitted for the killing of animals, the rooms it showed remained empty, painting a backdrop of violent and eerie subjectification. Like that project, “Figuer Sucia” is implicitly connected to Dean’s longstanding reflections on how Blackness is conditioned for and as social material. The contorted not-quite-object, not-quite-subject of FIGURE A might seem to show the implied, absent victim of that prior project. Yet “Figuer Sucia” calls the source of such brutality into question. It examines a violence that is not only in the scene we are witnessing, but …

May 20, 2021 – Review

Monika Baer’s “loose change”

Peter Brock

The six watercolors that greet the viewer when they enter “loose change,” Monika Baer’s second exhibition at Greene Naftali, offer a pared-down introduction to the artist’s habit of combining heterogeneous elements within the space of a single picture. In one sense, these modestly sized paintings are straightforward: splotchy pools of pigment on chunky paper with a few coins glued to their surfaces, sometimes in little clusters. The painted bits look casual, loosely composed, and unselfconscious. Faint lines meander through The Grove (2021) with such ease that they almost resemble accidental scratches from a bracelet or the dull end of a tool. Two of these works have fragments of small sawblades screwed into their surfaces. The watery dabs of paint in Loose Change (2021) seem not to notice the menacing metal teeth less than an inch away, whose rusted tips look weary but fierce. The literal and symbolic density of these metallic intruders contrasts strongly with the soft haze of the watercolor passages. At first it seems like the only relationship these chunks of metal have with the paint is that a few of the coins overlap with the colors.

Face Up (2021) contains a loose wash of pale blue …

October 10, 2019 – Review

Paul Chan’s “The Bather’s Dilemma”

Alan Gilbert

The figures in Paul Chan’s work have frequently been subject to powerful outside forces. In the large-scale animated video Happiness (Finally) After 35,000 Years of Civilization (After Henry Darger and Charles Fourier) (1999–2003), which helped garner Chan initial acclaim, a group of prepubescent girls with origins in Darger’s writings are threatened by a war raging around them. Every object in The 7 Lights series (2005–07) of digital projections is subject to the same gravitational pull. The physical and sexual violence depicted in black-and-white silhouette in the mural-sized and nearly six-hour-long digital video projection Sade for Sade’s sake (2009), created in the wake of the Abu Ghraib torture revelations, is larger than any one person; rather, it is institutional and endemic. Even Chan’s more documentary-style video essay, Baghdad in No Particular Order (2003), was shot during a visit to Iraq and ominously foretells a war that would leave hundreds of thousands dead and a country in near total ruin.

It is understandable that Chan eventually took a hiatus from these labor-intensive screen-based projects, and from the ubiquity of screens in general, while continuing to think about the centrality of images in a rapidly digitizing world. Recently, he has been producing bodies of …

October 18, 2018 – Review

Trisha Baga’s “Mollusca & The Pelvic Floor”

Leo Goldsmith

Trisha Baga’s third exhibition at Greene Naftali is also her most ambitious. “Mollusca & The Pelvic Floor,” like its cosmically hilarious and dizzyingly psychedelic predecessors, features a dazzling and untidy collection of found, handmade, and moving-image works: from doctored lenticular posters of human anatomy to idiosyncratic ceramic representations of everyday objects, all arranged around and within a deliriously complex 3D video installation.

Baga has made more than 40 ceramic pieces of various sizes and dimensions representing an array of often comical real-world objects. There’s a full rock-band set-up, complete with drum set, guitar, and tip jar; a log fire; a cardboard box with the Amazon swoosh logo; a portrait of Baga’s dog, Monkey, swimming; and a quintet of poodle heads in the shape of Mesoamerican pyramids (temples of the dogs?), with titles such as Kimberly and Butchie (both 2018). Encountering life-sized versions of a crumpled rhinestone Elvis suit or a cockatoo in the gallery, you get the feeling of entering the artist’s psyche—or, simply, of her ideas made flesh, birthed into the world in a way that’s as simultaneously magical and quotidian.

Baga’s ceramics have an amusingly DIY quality that both belies their complex material origins and butts up against the more …

February 13, 2015 – Review

Joachim Koester’s “Body Electric”

Pedro Neves Marques

“Nothing is true, everything is permitted.” A fine phrase for art, but just as eerily appropriate for politics in these days of technocratic, neoliberal control over “non-societies” jam-packed with contemporary “me only” pathologies—from entrepreneurship bullshit to non-dom tax evasion. What William Burroughs couldn’t possibly have imagined was how this iconic sentence from his Red Night Trilogy (1981–1987) would, in time, mirror another phrase, instated by Britain’s Iron Lady: “There is no alternative!”

Despite its close relationship with Burroughs’s work, in Joachim Koester’s solo show at Greene Naftali not everything is permitted. In the main room, anonymous bodies communicate, exasperatingly, in a language whose bodily grammar is found somewhere between hallucinogenic and repressed oblivion—all in a set of four moving image works. At its heart screens The Place of Dead Roads (2013), Koester’s video adaptation of Burroughs’s 1983 Wild West novel, which tells the time-traveling tale of gay gunslinger cowboy Kim Carsons, shot dead in 1899, who desires only to escape his body-prison out into the immortal cosmos. But Carsons is nowhere to be seen, either in the video or in the show. More important to the exhibition’s spirit is the series Some Boarded Up Houses (2009–2013) that greets us in the …

March 25, 2013 – Review

Gianni Colombo

Alan Gilbert

I don’t know if I’ve ever seen—and experienced—as much unadulterated glee in an art gallery or museum as I did at the opening of Gelitin’s “The Fall Show” at Greene Naftali last September. The gallery was filled with makeshift sculptures of different shapes fashioned from relatively cheap materials and placed on variously sized pedestals. Each pedestal had a foot pedal attached that rocked or jolted it, sending the sculpture perched on top crashing to the floor, usually with a loud thud or a sharp clatter. Some of the sculptures were dented and chipped by the end of the evening, and I can only imagine their condition by the close of the show. At the opening and in the weeks that followed, people took iconoclastic pleasure in toppling Gelitin’s artworks, which seems appropriate given the aura of exclusivity that still generally surrounds art (and its institutions), even after a decade or more of frequently overheated rhetoric—pro and con—regarding participatory and interactive art (along with its kissing cousin, relational aesthetics). In certain ways, Gelitin’s show felt like an absurdist exclamation mark emphatically inserted into this debate.

The much quieter, although not entirely silent, current exhibition at Greene Naftali follows participatory and interactive art …

November 10, 2011 – Review

Michael Krebber’s “C-A-N-V-A-S, Uhutrust, Jerry Magoo, and guardian.co.uk Paintings”

Antek Walczak

Let’s start this review typically, with a jaunty little narrative that encapsulates what’s happening in Michael Krebber’s latest show at Greene Naftali Gallery. Probably the most famous of Goya’s “Black Paintings” made between 1819-1823, painted directly onto the walls of his home at the time, the Quinta del Sordo (Villa of the Deaf Man), is that which goes by the name of Saturn Devouring His Children, one of six oil murals that adorned the dining room. (footnote 1) In his depiction of the myth of one of the Titans who ate his children in order to circumvent their youthful maneuverings in rendering him forcibly obsolete, Goya made Saturn’s eyes the focal point of the picture. With a crazed and bewildered look, the proto-Olympian gnaws on the arm of the headless corpse he clutches, less a deity in demeanor than a wild and formidable vagrant. Taken as allegory that transmits through the ages, adaptable and mutating, Goya’s work can fit any desperate world condition, but it’s Saturn’s eyeballs, with their lack of a gaze, or at least a pointed intelligence, that locate the horror and tragedy in the global contemporary art scene of 2011, and, in particular, in the paintings of …