“Often, the story of Tropical Modernism is told as one of a gift to Africa,” explains Nana Biamah-Ofosu, co-curator of the Applied Arts Pavilion in this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, “when in fact, it was a gift from Africa to the world.” The common telling of this history credits the husband-and-wife architectural partnership of Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew for bringing Modernism to British West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, Gambia and Sierra Leone) in the late 1940s. Their work was facilitated by colonial funding, which afforded them significant opportunities to test their modernist sensibilities and adapt them to the hot and humid climate. To Fry and Drew, taking a European style to this climate was a scientific affair, dressed in the language of climate control and was typified by architectural elements such as verandas and brise-soleil shading. With superficial architectural reference to their locality, their schools, community centers, and libraries were ground-breaking to European circles. Their work was firmly established in the European architectural canon through the publication of the influential book, Tropical Architecture in 1956.

However, single-room-deep typologies that encourage cross-ventilation and brise-soleil shading elements existed in the region for centuries before Tropical Modernism. With the intention of “complicating” the historical re-telling of Tropical Modernism, the Applied Arts Pavilion is a critically incisive exploration into the architectural style. Organized by The Victoria and Albert Museum and curated by Christopher Turner with Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed, the pavilion focusses on West Africa and examines Tropical Modernism from its colonial beginnings to its re-appropriation as an architectural symbol at the heart of newly independent Ghana. Within the period spanning from post-Second World War West Africa through to newly independent Ghana, architecture and different forms of power coalesced to test new modes of living in a decolonizing country.

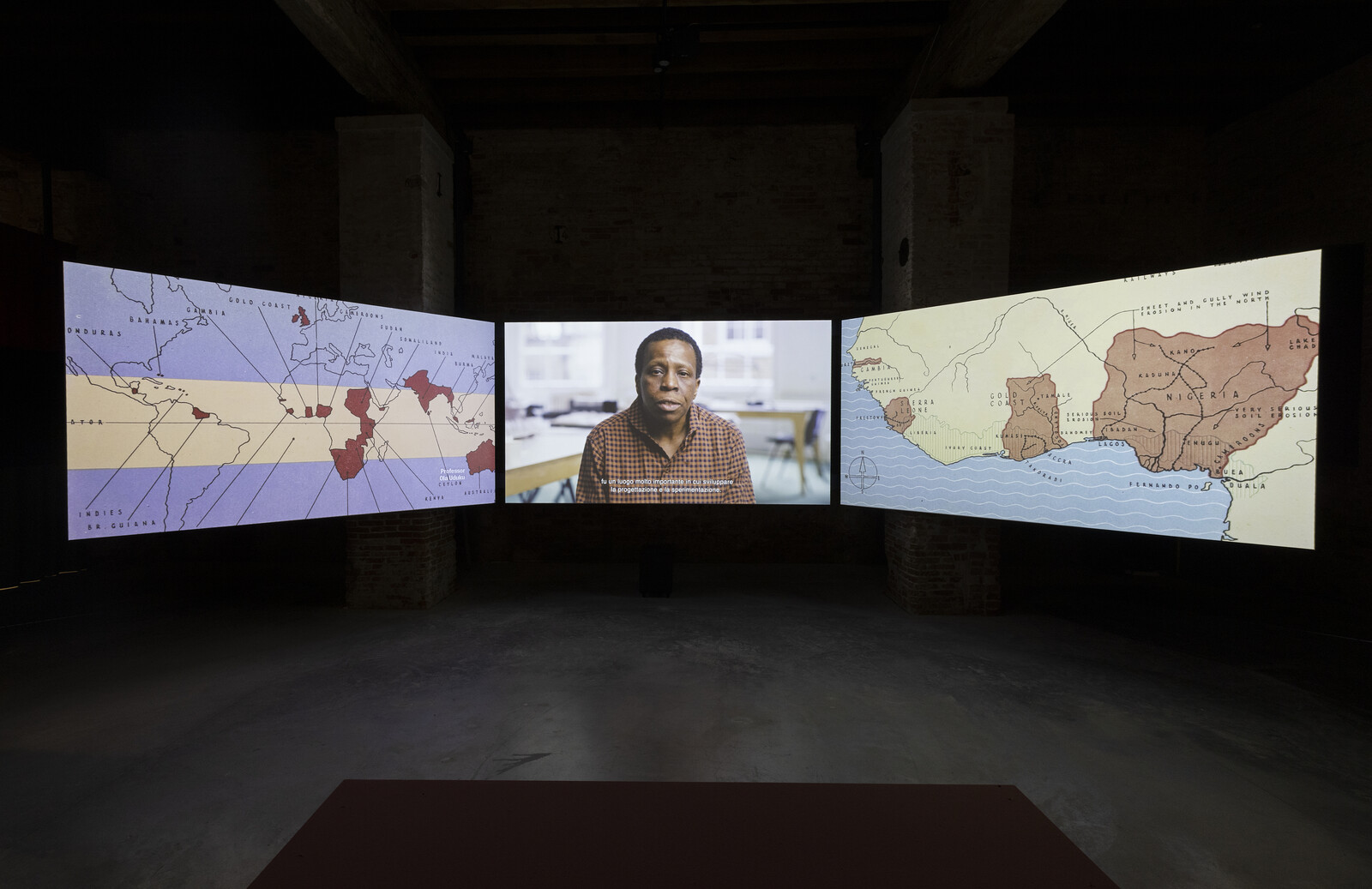

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

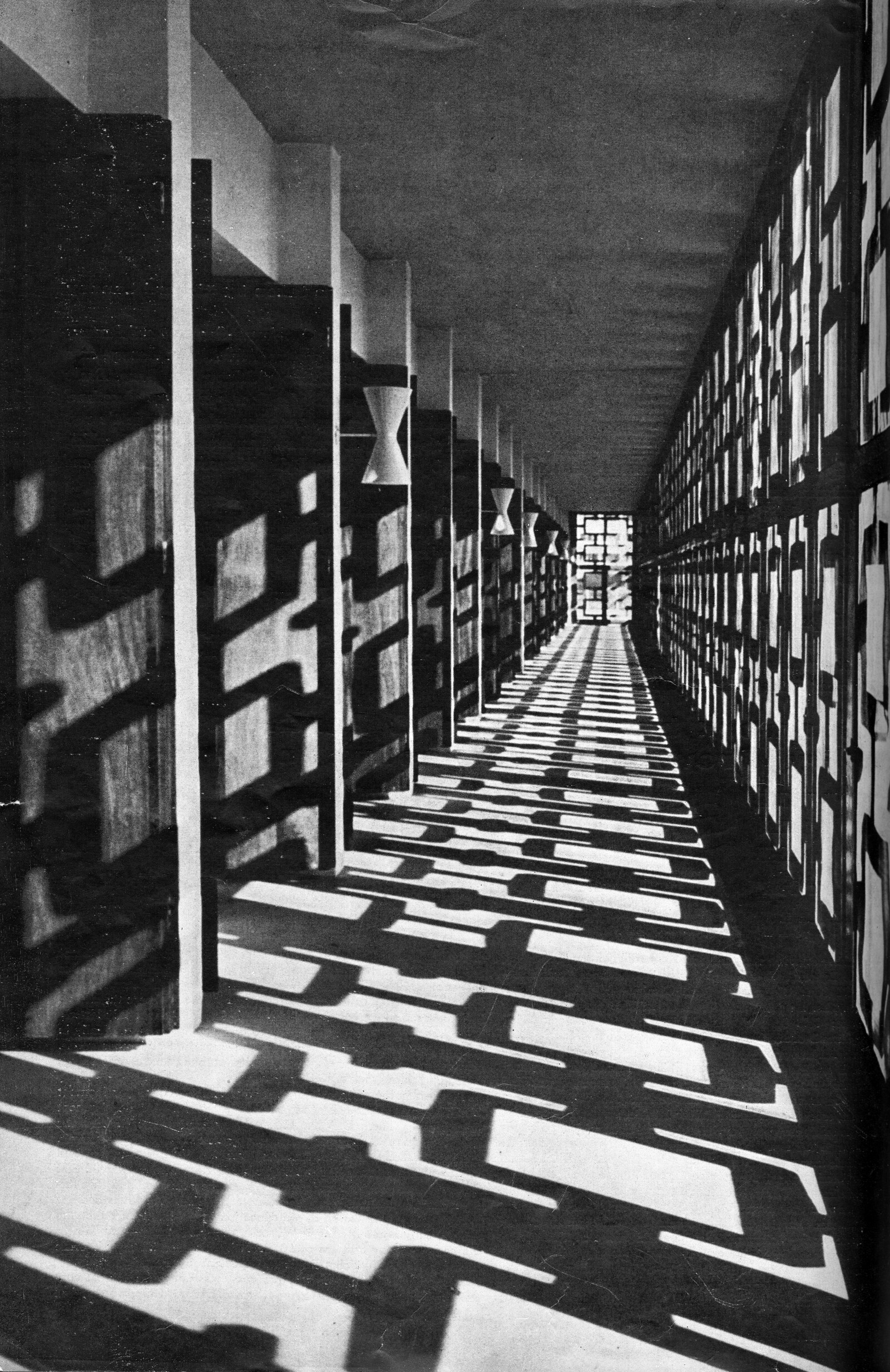

Upon entering the pavilion, a brise-soleil exhibition wall greets visitors and guides them through the space. Designed by Biamah-Ofosu and Mohamed, the wall is inspired by the brise-soleil pattern of Fry and Drew’s Kenneth Dike Library in Ibadan, Nigeria. The geometric pattern prominently features interlocking rectangular boxes, which here have been used to house the light boxes for a series of archival images and drawings. In close collaboration with Architectural Association (AA), London, and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, the archival images present architecture’s role both as a pacifying force in colonial West Africa and its emancipatory spaces of newly-independent Ghana.

Through a careful selection of images, Tropical Modernism’s relationship between power and architecture is delicately deconstructed. Although West Africa afforded many opportunities to Fry and Drew to develop their careers, they had an indifferent view of the region and cared little for the local culture or symbols. The exhibition takes a critical approach to their process, with Biamah-Ofosu questioning, “why are Fry and Drew known for their work in Chandigarh but their work in West Africa, which was the test-bed for many of those ideas, largely ignored?” The curators claim that the prominence of Fry and Drew in Tropical Modernism has been overstated, and name the African architects missing from this story like Theo Clarke, one of the first generation of qualified architects in the then-Gold Coast.

At the end of the exhibition wall, a twenty-eight-minute-long multi-channel film installation weaves together archival and present-day footage of everyday moments from several buildings from the period. The film, directed by Turner, Biamah-Ofosu, and Mohamed, is the impactful, center-piece of the pavilion. Opening the film, Ola Uduku discusses the role of coloniality, modernism, and architecture, before concluding that “West Africa did become the perfect laboratory for these things to happen.”

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Installation view of Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa at the Applied Arts Pavillion, Venice Architecture Biennale, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The film begins by exploring the role of Fry and Drew as “agents of the colonies.” They were given significant backing by the UK’s Colonial Office—a £200 million program—to “modernize” their colonies after WWII. Colonial maps and photos of colonial administrators are interspersed amongst images and sketches of buildings designed by the couple. In the Wesley Girls’ High School in Cape Coast, Uduku explains the role of verandas, cross-ventilation, and axial design in Fry and Drew’s conception of “Modernism in the Tropics.” Archival footage of the campus, which was completed in 1947 as an early missionary with a strong colonial presence, is placed side-by-side with present-day footage of celebration at what is now one of Ghana’s top performing schools.

The film also engages with the Community Centre in Accra, which was completed by the couple in 1953. Described by Uduku as a “tool of pacification,” it was designed against a backdrop of political unrest and decolonial struggle, with Kwame Nkrumah returning to the Gold Coast in 1947 to lead the independence movement, and after the 1948 Accra Riots in which the United African Corporation headquarters was burnt down. In spite of this explicit colonial project of de-escalation, on the facade of the building’s main entrance, a mosaic by Kofi Antubam—who later became Nkrumah’s state artist for independent Ghana—depicts an everyday scene that centers Ghanaian everyday culture and the pan-African ideals that were soon to come. In the local language Ga, it reads “Kwe boni ehi ke nyemimei fee ekome kehi ei le” (“It is good we live together as friends and one people”).

The film joins footage of the mural followed by archival footage of the independence movement. Ghana gained independence in 1957, with their first president, Kwame Nkrumah, believing that architecture would play a key role in his vision of an independent Ghana alongside pan-African politics. Tropical Modernism would thus be subverted from its colonial beginnings to become a postcolonial nation-building tool. To quote Nkrumah in the film: “where we find the methods used by others that are suitable to our social environment, we shall adopt or adapt them. This mid-twentieth century is Africa’s.”

The Northern Territories Chiefs at an exhibition for Volta River Project, a key project for Nkrumah’s vision for Ghana, 1950–59. Courtesy of The National Archives, Kew, UK.

Kwame Nkrumah and Queen Elizabeth II during her 1961 visit to Ghana. Photograph by Michael Welch. Courtesy of the AA Archive.

Mural on the main façade of the Community Centre. Written in Ga, the mural by Kofi Antubam reads “It is good we live together as friends and one people.” Courtesy of the RIBA Collections.

The Northern Territories Chiefs at an exhibition for Volta River Project, a key project for Nkrumah’s vision for Ghana, 1950–59. Courtesy of The National Archives, Kew, UK.

Samia Nkrumah, Kwame Nkrumah’s daughter, explains how her father believed that Ghanaian independence was meaningless unless it was connected to the total liberation of Africa. Architecture’s role in projecting a confident image of a new Ghana and the potential of a liberated Africa to the world was therefore of paramount importance. Following Ghanaian independence, there was a major development push, with Nkrumah inviting architects from Eastern Europe to extend his pan-African ideals beyond and into the global territory of the Non-Aligned Movement. Footage of Independence Square in Accra alludes to these histories, with the monumental form of Independence Arch featuring a double arched gate that was informed by Soviet architectural references.

Nkrumah also believed in the “Africanization of professions,” encouraging practices set up in Ghana to have Ghanaian architects to lead their work. Victor Adegbite became the country’s Chief Architect, with John Owusu Addo and Max Bond later also becoming key figures in transforming Tropical Modernism from a colonial tool to a symbol of pride in postcolonial Ghana. As Henry Nii-Adziri Wellington explains, “A building from Ghana must show the evidence that it is Ghanaian… The people’s culture, the economy, their circumstances must be reflected in the buildings. All these things have deep psychological and spiritual significance, which the British architects did not take time to understand.” Thus in reappropriating the colonial tool of Tropical Modernism, Ghanaian architects looked to local symbols and culture to make the style suitable for a politically ambitious and newly independent nation.

Parallel to this history in Ghana, the Department of Tropical Architecture was set up at the Architectural Association in 1954 in response to a complaint by Nigerian student Adedokun Adeyemi that his university training was inadequate in preparing him for work in Africa. It was first directed by Maxwell Fry, before Otto Königsberger took over in 1957. Under Königsberger, the department took a more scientific and research-based approach, teaching Tropical Modernism as the solution to local climatic issues. With a western bias, the department mostly disregarded and overlooked traditional architecture from the region, despite its centuries-old practices of dealing with its own climate. In treating architectural projects in Africa as a monolith to which western technological solutions could be imported, the Department of Tropical Studies, as renamed by Königsberger, only reflected the colonial origins of Tropical Modernism. In the notorious history of the Architectural Association, the Department of Tropical Architecture is still seen to be an odd quirk of its history. It has not been viewed as an intrinsic part of its culture, and there has been little acknowledgement of the AA’s historical adjacency to colonial practices. This is hopefully changing, however, as both Biamah-Ofosu and Mohamed currently research and teach there.

A jury at the Department of Tropical Architecture at AA in the 1950s. Kamil Khan Mumtaz (right) would go on to teach at KNUST between 1964–66. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

Academic staff procession in front of Registry building, KNUST graduation, 1965. Courtesy of Patrick Wakely.

Students and faculty working on a Buckminster Fuller inspired geodesic structure. Photograph by Keith Critchlow. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

Department of Tropical Studies brochure illustrating the tropical zone, c. 1960s. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

A jury at the Department of Tropical Architecture at AA in the 1950s. Kamil Khan Mumtaz (right) would go on to teach at KNUST between 1964–66. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

In 1963, the AA partnered with Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), with students going in both directions to share ideas and develop techniques suitable for tropical architecture in Ghana. John Lloyd was sent from the AA to Kumasi to lead the new course at KNUST, and had a much more sensitive approach to architecture in Ghana when compared to Fry and Drew. Although this was a post-colonial framework between Ghanaian and British institutions, this collaboration was seen as more mutually beneficial than the previous history of colonial architectural imposition. Uduku explains that Lloyd encouraged students to appreciate their context, architectural history, and sociology in developing their designs. For the first time, traditional African architectural forms became part of the curriculum, taught by a number of Ghanaian architects. Modernism would no longer be imported from the West. Instead, young Ghanaian architects would be taught to engage with social and cultural history to develop a new vision for an African future.

Beyond this exhibition, a larger project has recently begun as a research partnership between the V&A, AA, and KNUST to investigate the shared cultural history between these institutions. The research of this pavilion will contribute towards an exhibition at the V&A to open next year, looking at Tropical Modernism more broadly beyond its influence in Ghana. As part of this collaboration, KNUST are maintaining, collating, and building their archives in order to learn from this history. Beyond this critical reflection of the Tropical Modernism period, the tangible benefits to contemporary learning at KNUST is an important legacy of this exhibition to today’s KNUST students.

Africa Hall at KNUST, Miro Marasović, Niksa Ciko, John Owusu Addo, 1965. Photograph by Michael Dylan Welch. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

Precast concrete brise soleil at University of Ibadan library by Fry, Drew & Partners, 1955. Courtesy of the RIBA Collections.

Bolgatanga Library designed by J.Max Bond Jr for the Ghana National Construction Corporation, 1965. Courtesy of the private collection.

Spectators watch football under the in-situ cast concrete roof structure of Paa Joe’s sports stadium, KNUST, 1961. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

Africa Hall at KNUST, Miro Marasović, Niksa Ciko, John Owusu Addo, 1965. Photograph by Michael Dylan Welch. Courtesy of the AA Archives.

The KNUST campus itself features a number of Tropical Modernist buildings designed by Ghanaian architects John Owusu Addo and Samuel Opare Larbi alongside British and Yugoslavian architects, which Uduku calls “Bauhaus in the tropics.” Rather than a city campus, it emerges from a verdant forest. Bold modernist geometries of the School of Engineering by James Cubbit & Partners stand alongside the mesmerising use of brise-soleil walkways over eight-storeys on Africa Hall designed by John Owusu Addo. This is a holistic campus vision, designed to inspire the students to dream of what Ghana’s future could look like.

Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown in a military coup in 1966, a few years after declaring the nation a one-party state and with the nation almost bankrupt. While Nkrumah had secured political independence, economic independence was more difficult to realize. Its ambitious construction program was halted as the nation moved from the postcolonial and pan-African politics of Kwame Nkrumah towards a number of military leaders after the coup. This effectively signaled the end of Tropical Modernism in Ghana, with John Lloyd returning to the AA in the same year and the Department of Tropical Studies closing in 1971.

While the style is no longer dominant in Ghana today, this period of Tropical Modernism is a pertinent case study for tackling the issues of decolonization and decarbonization today. The re-appropriation of a colonial architectural language to become a symbol of the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence is compelling. The deep understanding of place, culture, and symbols within the work of Ghanaian architects such as Victor Adegbite and John Owusu Addo form a strong reference in designing spaces for the African diaspora.

Perhaps even more pertinent is the climate crisis, where the lessons of Tropical Modernism and its centering of environmental comfort and natural ventilation will only become more relevant. The introduction of air-conditioning helped to bring Tropical Modernism to an end. Designing for a decarbonized world will only be possible with passive environmental thinking and a move away from an overreliance on air-conditioning. Tropical Modernism gives strong precedent and design clues in tackling these future issues, but more testing needs to be done. As Uduku questions as the film comes to a close, “how can we make the tropics another laboratory for future experiments around living in the twenty-first century?”

Recently, current Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo has aimed to revive Nkrumah’s legacy, similarly using architecture as a tool for putting Ghana on the world stage. Within this, David Adjaye has effectively become the nation’s de-facto Chief Architect, having been commissioned for the National Cathedral of Ghana, the Agenda 111 program—which will build over 100 hospitals across the country—and pertinently, Marina Drive Accra, which revives masterplans from Nkrumah’s era around Independence Square. While there are only early concept images, Marina Drive Accra is a particularly perplexing proposal, as its images propose a number of generic, glassy towers next to the iconic symbols of Independence Square. Overlooking the socialist and pan-African ideals of Black Star Gate and Independence Arch, today Adjaye proposes an opportunistic and speculative redevelopment that pays homage to the Nkrumah era in name only.

The work of Adjaye Associates was prominently displayed within the Central Pavilion of the Giardini, including the National Cathedral project. This is a significant nation-building project first unveiled in 2018, described on their website as a place where “religion, democracy, and local tradition are seamlessly and symbolically intertwined.” While the grandiose ideals of architecture, power, and society are there, architecturally little has been learnt from Tropical Modernism. The tent-like swooping concrete structure lacks the bold geometry of post-independence Tropical Modernism and generically claims to reference “ceremonial canopies,” while the cathedral is thermally enclosed and likely air-conditioned, making little use of the natural ventilation that Tropical Modernism is known for. Furthermore, the presentation of the pristine wooden model of the National Cathedral in the Central Pavilion is divorced from the controversy that surrounds this particular project.1 The recent allegations of sexual misconduct in the workplace made against Adjaye only exacerbate the necessity for pause and reflection upon the culture through which such architecture is produced.2

Personal ambition, ego, and poor working culture is not unique today in Adjaye and his work for Akufo-Addo. It is also not particularly controversial to say that megalomania inspired Kwame Nkrumah in his visions of building a confident image of a newly independent Ghana. In the film, John Owusu Addo even went as far as to say that “[Nkrumah] was a very good African, but a very poor Ghanaian.” Despite this, Nkrumah’s personal ambitions were closely entwined with socialist principles and a pan-African vision that aimed to use architecture as a tool for the liberation of all Africans. As present-day Ghana under Akufo-Addo looks back to the Nkrumah era, the buildings from the post-independence Tropical Modernism era stand as a firm reminder that architecture and power can in fact coalesce to create a meaningful and inspiring symbol in tackling the twin challenges of decolonization and decarbonization.

Construction on site was stopped last year after concerns around how much public money had gone into the scheme, and significant questions around Adjaye’s procurement have also been raised, with no evidence of a competitive tender and calls for the promotion of local architects instead. Will Ing, “Adjaye Under Scruitiny Amid Ghana Cathedral Controversy,” Architects Journal, June 27, 2022. See ➝.

Josh Spero and Anjli Raval, “Sir David Adjaye: the celebrated architect accused of sexual misconduct,” Financial Times, July 4, 2023. See ➝.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Subject

This essay was commissioned as part of a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and alumni from the fourth cohort of New Architecture Writers to publish reviews of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale and Lesley Lokko’s 18th International Architecture Exhibition, “The Laboratory of the Future.”

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)