Partitions of territory are often ascribed to historically specific moments of accountability. While colonial partitions set the terms for politics and life in Bengal, Ireland, Somalia, Palestine, and elsewhere over the course of the twentieth century, the term “Partition” has become iconically associated with the division and inscription of nation-states in South Asia in 1947. The cartographic commitment of the jurist Cyril Radcliffe, “having never set eyes on the land he was called to partition,” as W.H. Auden memorialized it, turned a brief mission to India into a historically contained moment.1 The repetition and reinscription of that narrative occasions our argument to follow. To account for partitions in South Asia and elsewhere is to move beyond one moment, beyond the architecture of a line. It is to recognize and interrogate—beyond event, and towards concept—the political form within the spatial as partitions continue to drive the reorganization of lands and landscapes.2

The Partition of 1947, which for parts of South Asia accompanied freedom from British colonial rule and created the nation-states of India and Pakistan, was a catastrophe not just because more than three million people were killed and some twenty million people were displaced over the months and years that followed.3 While the threshold date and these ghastly numbers are a record of wrenching scale, “partition”—as a spatial reorganization of a landscape, of cities, and of neighborhoods—continues to unfold across South Asia, producing liminalities that ignite new kinds of policing and further violence.

Instead of the provisional Radcliffe Line, let us begin with two considered floorplans of ancestral homes in Aligarh and Jaffna. The first, a woodblock print with metal-cut text in the portfolio Letters from Home (2004) by Zarina, defied loss and dispossession through an assertion of architecture, literary culture, and familial bond. In it, she notates a world her family was forced to evacuate, a decade after the Partition of India in 1947. Over a letter from her sister, she printed a floor plan of a home that she could no longer return to, which lay bereft, empty, in ruins in her memory. The second, a pencil on trace paper entry in The Incomplete Thombu (2012) by Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan, archives fracture and names the systematization of displacement in the 1980s during the war between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The house drawn in this plan and the land around it were occupied in 1987 by the Indian Peace Keeping Force and became a killing field. For the woman who sketched it, this floor plan holds the broken body of her son. These artworks inscribe into the firmament of lines the unspeakable grief of dispossession, the loss of homes and lives. Architectural history, drawn from archives of state officials, urban planners, and architects accounts for new national visions and designs, and yet often fails to address how these have been built into and over the ruins and ravages of a founding violence, and the political forms this violence continues to generate.

“Partition” is a concept that declares the historic plurality of lived worlds untenable, and sets about transforming differences into incommensurability. This process is never self-evident or voluntary. For people who have lived together over centuries, even in neighborly prejudice and conflict, only a state-induced rupture cleaves people apart. Even then, there are those who remain in-between, or indeterminate; those who refuse sides, or refuse to leave.

Living together is a spatial and architectural formation. Severing people comes with a material reorganization of the old world through dispossession, destruction, and occupation, or the establishment of camps for the indeterminate and the undesirable. Through the spatial reorganization that “partition” demands, the formations of citizenship and statelessness go hand in hand.4

Photograph of a convoy of people, including communities of Sikh farmers, migrating to East Punjab with belongings and livestock, naturalized within the landscape as part of the “Great Migration” series. Margaret Bourke-White, Migration in India (1947).

Ruins of Evacuation

When the Partition of 1947 is remembered in terms of the genocidal bloodletting that took place in parts of northern India, when religion was made the basis of dividing populations, then mass displacements of people appear to be entirely a consequence of this violence. Monumental photographs of the train and foot convoys, such as LIFE magazine’s “Great Migration” photographs by Margaret Bourke-White, suggest that this population exchange was a “natural” flow of people.5 Yet, state interventions and planning shaped these displacements and reordered centuries of built worlds, then and to this day.

Homes that people left behind and could no longer return to came to be governed by the Custodian of Evacuee Property. An adaptation of a wartime British institution used to usurp “enemy” property, it took over the homes and lands of those fleeing violence, and as it came to be extended to almost all of India and Pakistan, quickly became an instrument of partitioning along religious lines. It took over not only the homes and lands of “evacuees,” those who had fled, but also those imagined as leaving: creating the ambiguous category of “intending evacuees,” it dispossessed one religious community to give occupations to refugees of another.6 As religious minorities were forced out of dense, multi-religious neighborhoods that had been forged over generations, these evacuations and occupations haunt these cities to this day. Names left on buildings, abandoned temples, perfumeries, bakeries, and other small businesses continue to signpost roots and uprooting. Partitions violently created the territorial contours of new nations, and are inscribed everywhere into built forms.

The Partition of 1947 was driven by the Muslim question in India, about where Muslims as a political community belonged in the new age of nationalism.7 This idea, of partition, thrust all religious minorities, but especially those who remained where they had always lived, into new liminalities within and between nation-states. While some Muslims became citizens of the newly carved Pakistan, equally large numbers became Indians, trailed by the specter of political and spatial incommensurability. In cities like Delhi, the new Nehruvian state planned “Muslim zones” as part of its commitment to inclusion under secularism, to provide enclaves for the safety of those who stayed on.8 Muslim ghettos have ever since been stigmatized as “mini-Pakistans,” and anti-Muslim violence has often included the taunt of “go to Pakistan.” The spatial logics of omnipresent partitions organize how we live with difference now.

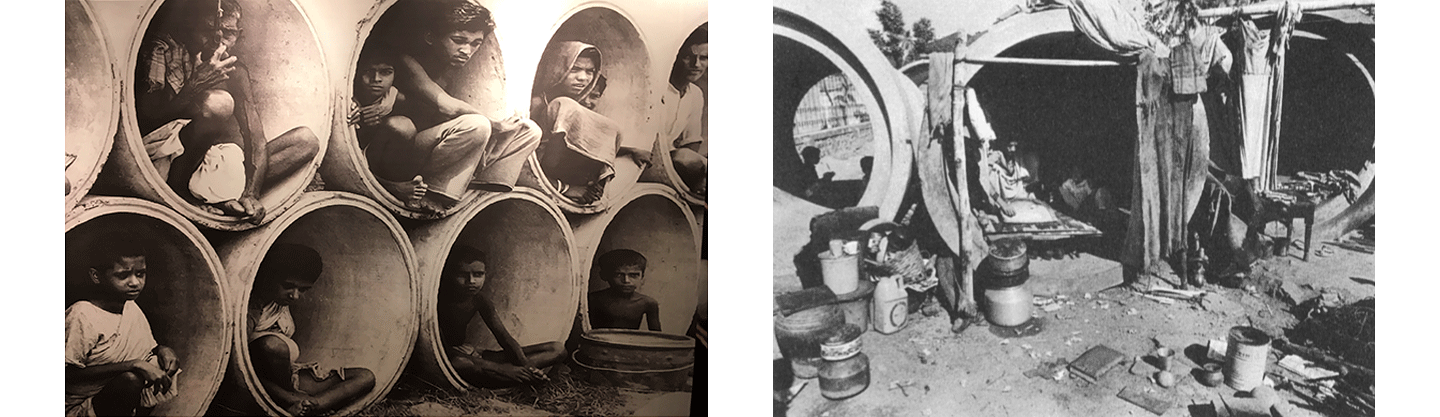

Left: Children and their families living in concrete water pipe sections, which sheltered an emergent Bangladesh in the Salt Lake refugee camps in Calcutta in 1971. From the permanent exhibition of the Liberation War Museum, Bangladesh (photo of exhibit: Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, 2018). Right: Photograph of the urban material domesticities of concrete water pipe sections, infrastructural fragments repurposed by migrants to house themselves. From the 1986 Vistāra exhibition curated by Charles Correa. See Carmen Kagal ed., Vistāra: The Architecture of India (Bombay: The Festival of India, 1986).

Planning the Nation

Where refugees could not be accommodated in the homes and lands of those “evacuated,” densely inhabited camps, unplanned but not without design, offered a highly regulated yet perennially temporary spatial arrangement. Within and beyond South Asia, refugees and refugee camps became constitutive elements of nation-state formation as well the production of statelessness. Structures such as concrete drain-pipe sections, eventually incorporated into a liberal modernist architectural discourse as representing an “un-celebrated” urban “ingenuity,” sheltered the future of emergent nations.9 Materially, the dispossessed, and not just modernist visions, shaped urbanism in South Asia.

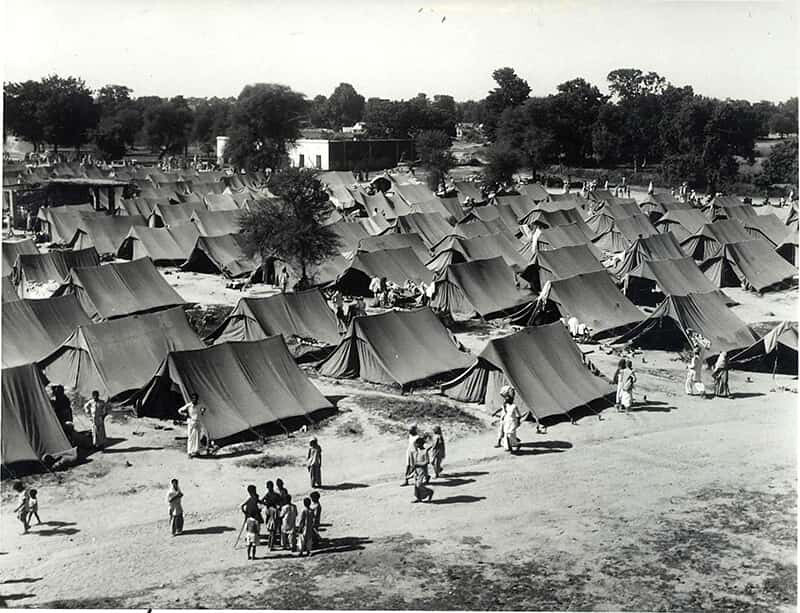

Families separated while crossing the borders were reunited in tents at Kingsway camp, Delhi, where refugees were housed when they could not be accommodated in the barracks at the ends of multiple rail lines. Photo courtesy of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. See also Sriya Rane, “A Refuge Called Hudson Lane,” DU Beat: An Independent Student Newspaper, June 20, 2019.

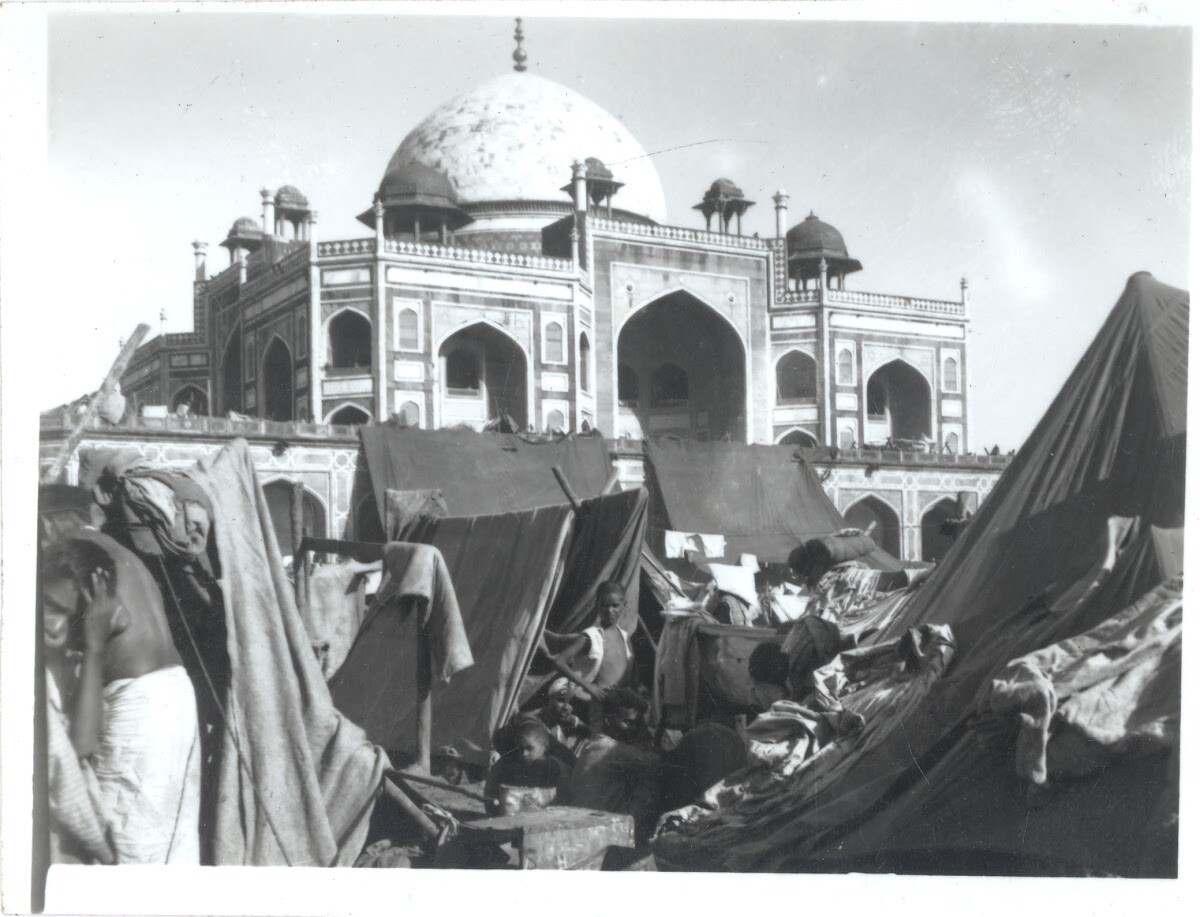

Between the censuses of 1941 and 1951, as partitions uprooted millions of people, the populations of the two capital cities, New Delhi and Karachi, tripled with the arrival of refugees, and the first formal urban planning endeavors of the new nation-states were undertaken as a consequence. Many non-Muslim refugees who arrived in Delhi from the devastations of Punjab settled in Kingsway Camp, a field of tents, textiles, and tin roofs. The Muslims of the city, displaced violently from their homes, sheltered in the shadow of Humayun’s Tomb, the Qutb Minar complex, and other historic Islamic architectural sites, shaping the materiality of a refugee occupation of the city and a logic that carried through the first post-Partition decades, as these first refugees were replaced by others in the shadow of the same monuments. This was demonstrated, for example, at the Purana Qila, which evolved from the humanitarian relief zone known as “Muslim Camp” to a Hindu- and Sikh-inhabited monument claimed to be the “violated” archaeological remnant of mythic Indraprashtha.10

Refugee camp at Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi, September 1947. Photo courtesy of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library and Google Arts and Culture.

Just as Delhi’s population swelled with refugees, so did Karachi’s, stoking anxiety and debates about how to house refugees in the midst of the old Hindu communities in a small sleepy port city unprepared for a national role. In 1953, the Karachi Development Authority was formed to address this housing crisis. In parallel, Delhi swallowed neighboring territory, which belonged to farmers and indigenous people. After nearly twenty settlements for housing societies were established, an Act of Parliament constituted the Delhi Development Authority in 1957. By the mid-1950s, Delhi had become an asymmetrical home to two million inhabitants, variously housed or unhoused—in private or public developments, government housing or slums, adaptations of the old walled city of Shahjahanabad, high- and low-rise apartments in medium density green environments, or camps-cum-squatter settlements.11

Housing for civil servants and government officers, designed by Habib Rahman for the Central Public Works Department. Multi-storeyed flats in Ramakrishnapuram. Photograph courtesy Madan Mahatta Archives and PHOTOINK

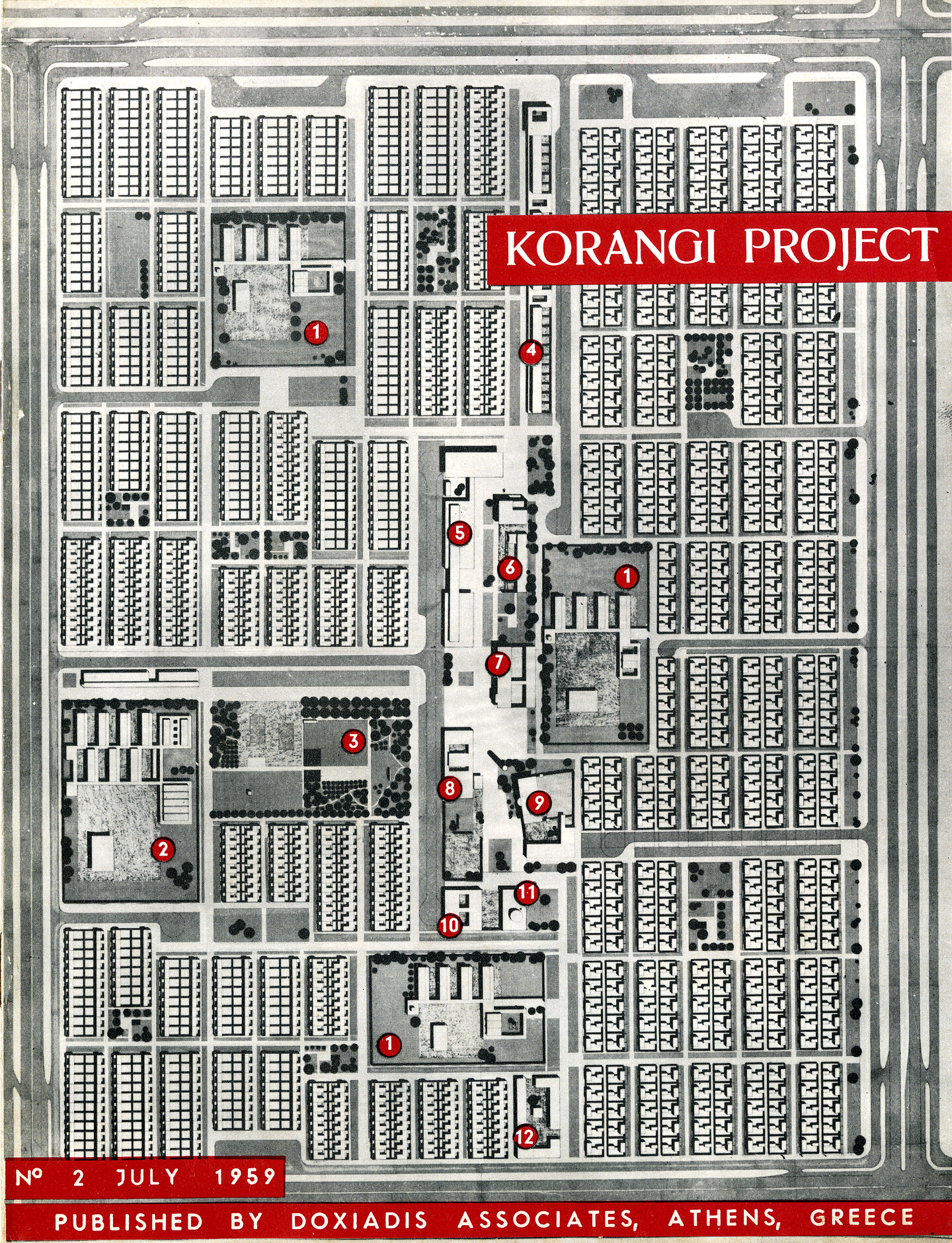

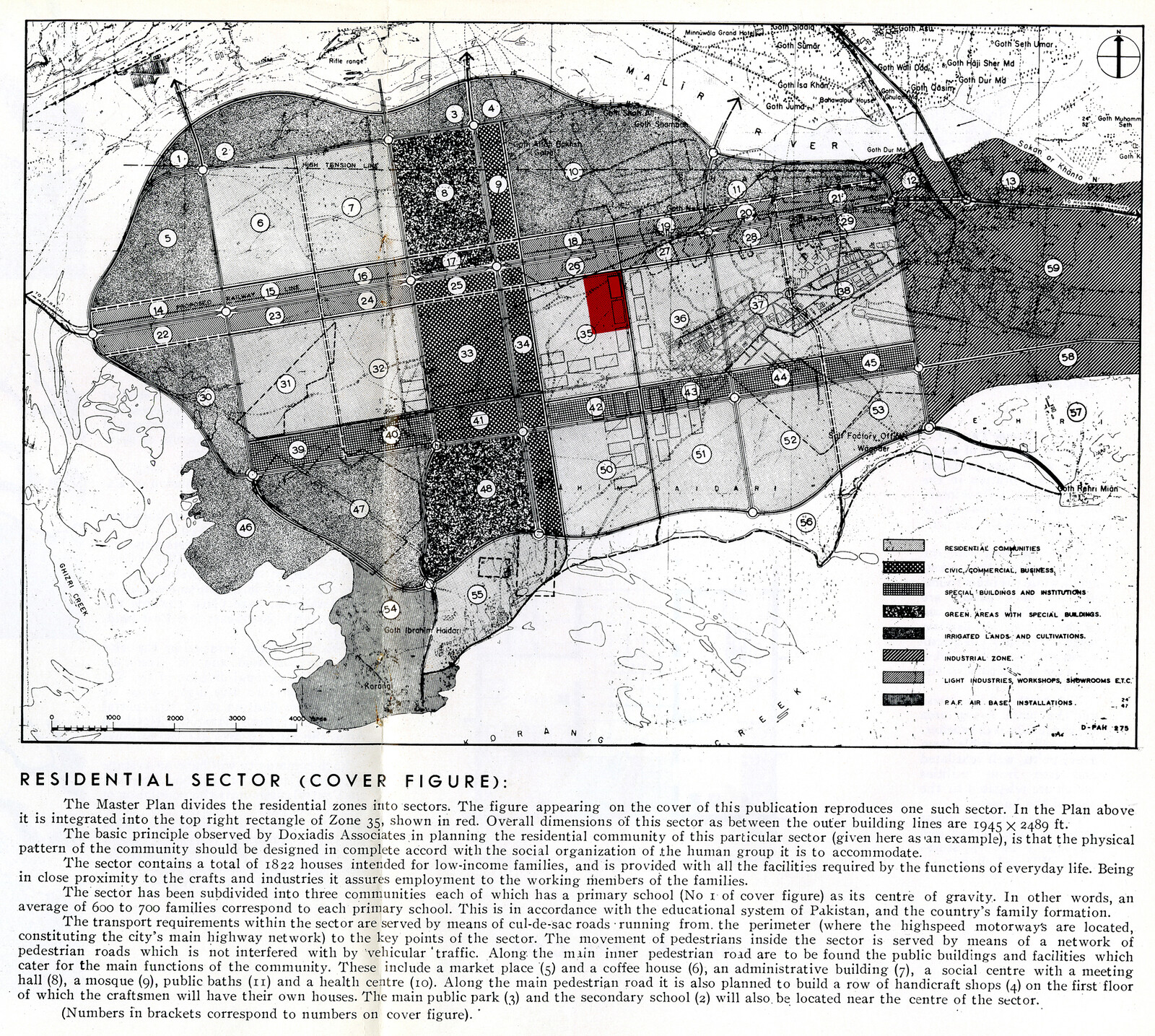

Doxiadis Associates Monthly Bulletin no. 2 (July 2, 1959), Korangi Project, Karachi. Cover illustration showing low-income residential sector for 1,822 houses, three community schools serving six to seven hundred families each and one secondary school, an administrative building, a social center with a meeting hall, a mosque, public baths, a health center, a public park, a coffee house, a marketplace, and a row of handicraft shops with integrated housing for craftspeople above. © Constantinos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation.

Doxiadis Associates Monthly Bulletin no. 2 (July 2, 1959), Korangi Project, Karachi. Extract providing context for cover illustration. © Constantinos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation.

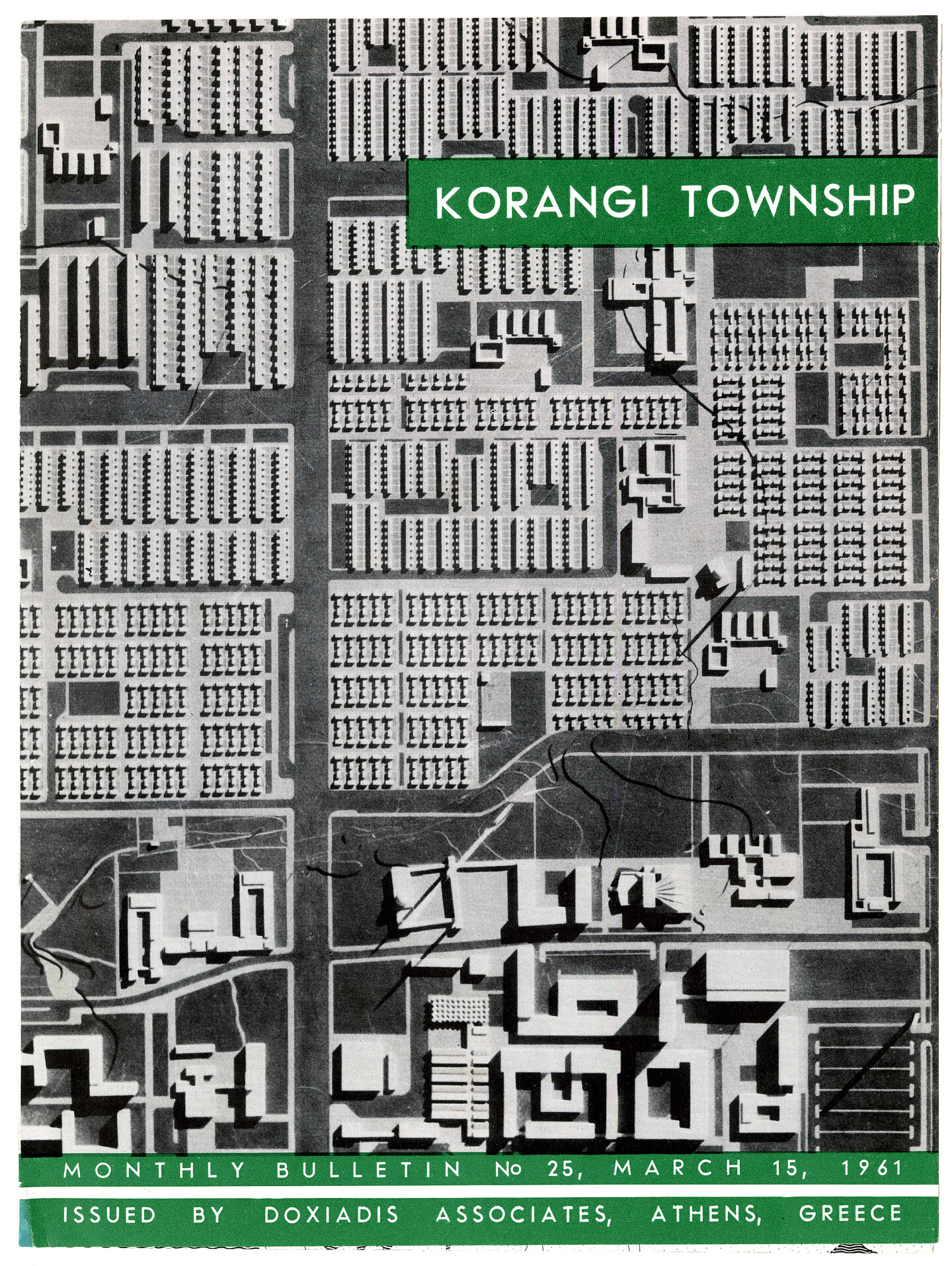

Doxiadis Associates Monthly Bulletin no. 25 (March 15, 1961), Korangi Township, Karachi. Cover illustration showing plan of residential and civic areas. © Constantinos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation.

Doxiadis Associates Monthly Bulletin no. 2 (July 2, 1959), Korangi Project, Karachi. Cover illustration showing low-income residential sector for 1,822 houses, three community schools serving six to seven hundred families each and one secondary school, an administrative building, a social center with a meeting hall, a mosque, public baths, a health center, a public park, a coffee house, a marketplace, and a row of handicraft shops with integrated housing for craftspeople above. © Constantinos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation.

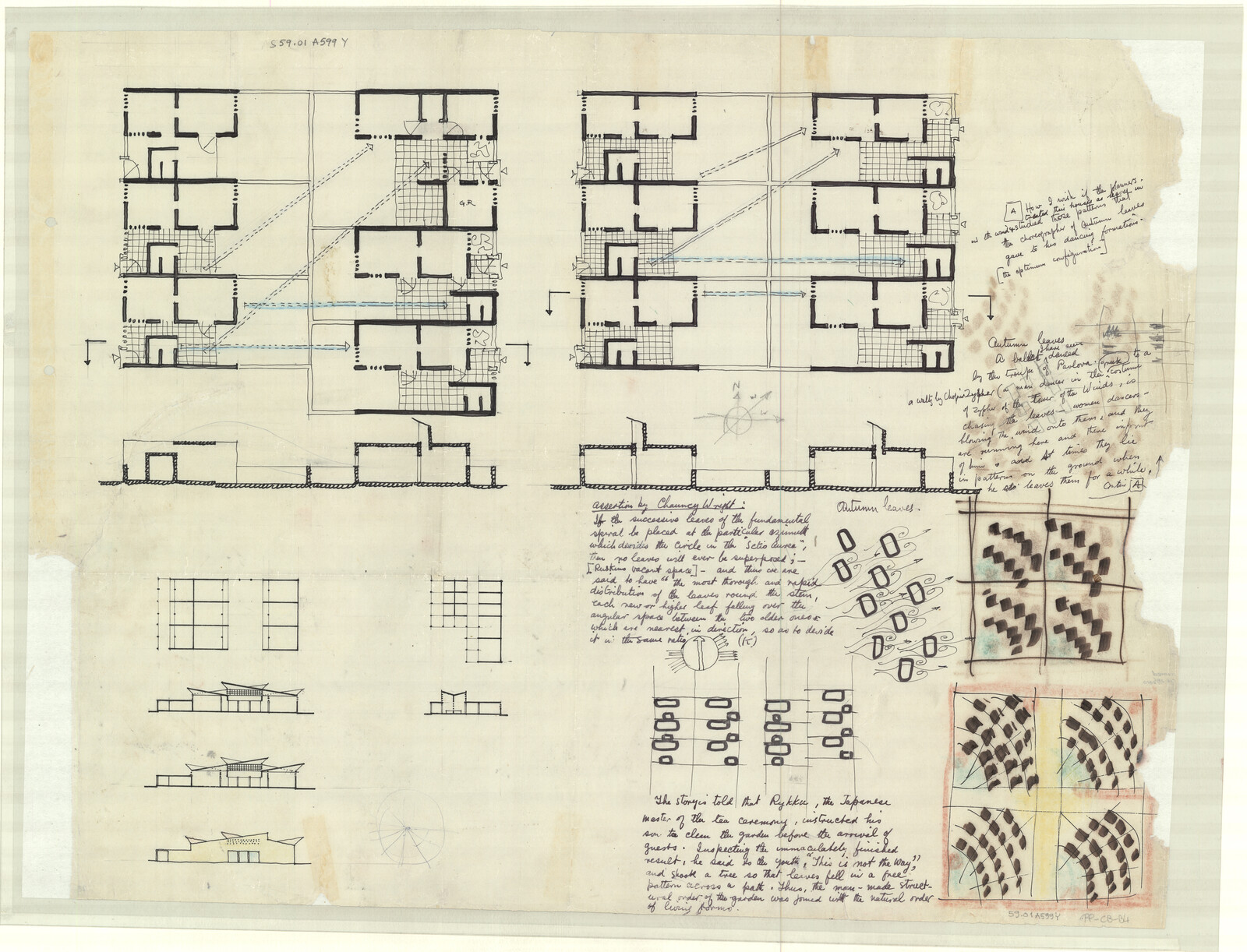

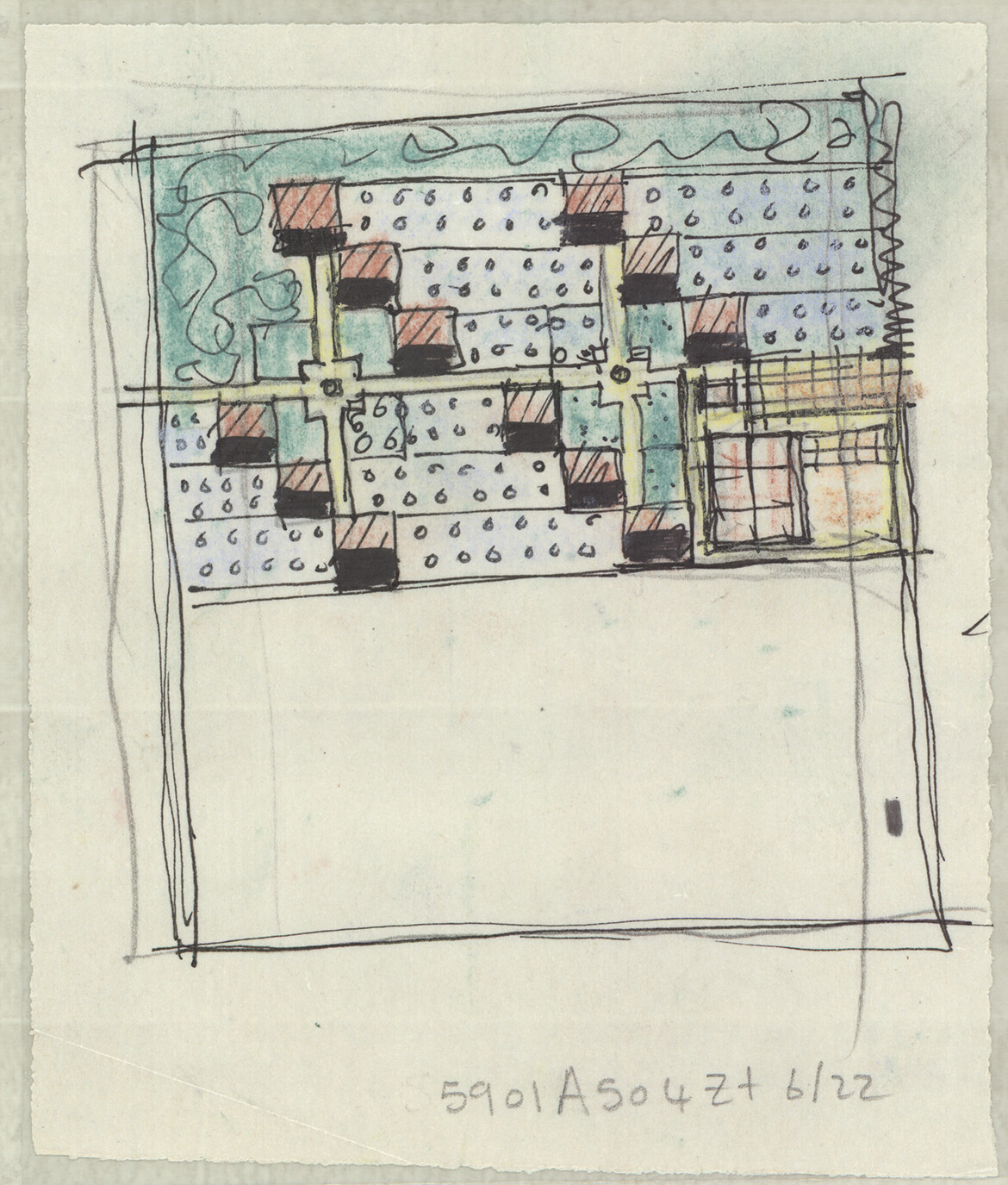

Hassan Fathy, housing study, Korangi Project, Karachi, 1959. Fathy worked for Doxiadis in Greece between 1957 and 1962, collaborating on planning projects in Pakistan and Iraq, and designing the central area of the Korangi scheme including the mosque, school, public buildings, and typical housing units. Courtesy of Hassan Fathy Architecture Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo, Egypt (Hassan Fathy Collection AUC RBSCL).

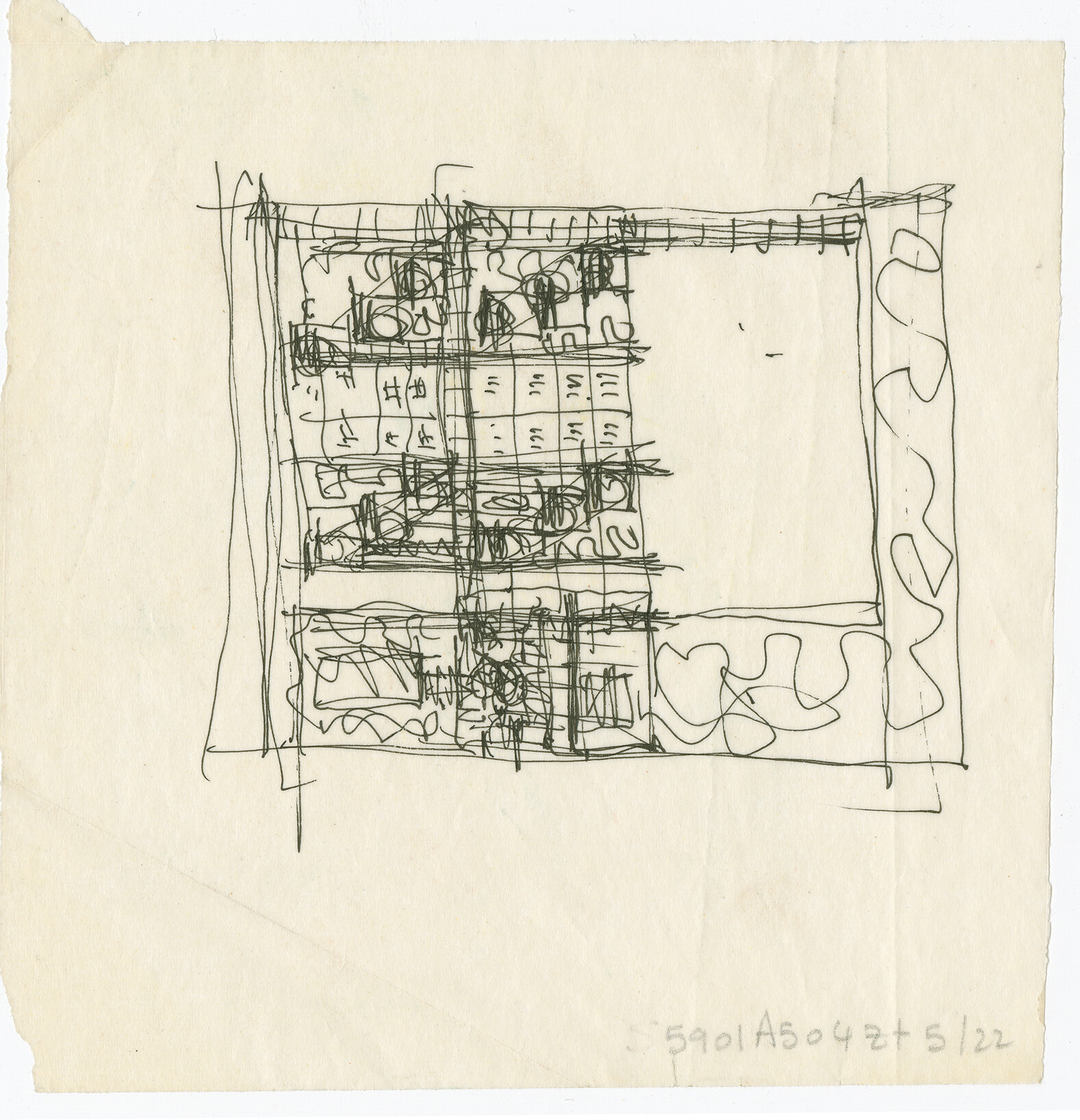

Hassan Fathy, conceptual study (possibly for the school), Korangi Project, Karachi, 1959. Courtesy of Hassan Fathy Architecture Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo, Egypt (Hassan Fathy Collection AUC RBSCL).

Hassan Fathy, conceptual study (possibly for the school), Korangi Project, Karachi, 1959. Courtesy of Hassan Fathy Architecture Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo, Egypt (Hassan Fathy Collection AUC RBSCL).

Hassan Fathy, housing study, Korangi Project, Karachi, 1959. Fathy worked for Doxiadis in Greece between 1957 and 1962, collaborating on planning projects in Pakistan and Iraq, and designing the central area of the Korangi scheme including the mosque, school, public buildings, and typical housing units. Courtesy of Hassan Fathy Architecture Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo, Egypt (Hassan Fathy Collection AUC RBSCL).

As the Pakistani state received international aid from the Ford Foundation and USAID in coping with refugees, and quickly thereafter adopted a Cold War alliance with the United States, its governments, including military dictatorships, received funding replete with architectural “assistance.” This design and development aid contoured the architecture and planning of many of its decolonizing cities and eviscerated the robust democratic politics promised by anticolonial struggles. The refugee resident of housing projects such as the planned Korangi Township in Karachi was a transitory figure upon whom were projected aspirations of the state and the international order—for structural sovereignty, political alignment, and economic development—vis-à-vis the architecture of housing. Yet, the shapeshifting of this liminal figure—identified as the citizen, yet not belonging, at once housable and evictable—enabled the spatial slippages and effacements necessary for continuous reproductions of structural power under authoritarianism.

Of Karachi’s development schemes, housing plans of satellite sites such as Korangi, though few in number, have become familiar through the archives of celebrated figures such as Michel Écochard, Constantinos A. Doxiadis, and Hassan Fathy—Doxiadis Associates proposing a Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan to the Pakistani government.12 Other urbanisms, however, of neighborhoods formed by refugee associations that had been turned into cooperative housing societies, such as Jamiyat Punjabi Saudagaran-e-Delhi (referring to those displaced from old Delhi), are absent in the architectural archive, voiding histories of ongoing struggles for democratic belonging and rights.13

Fluorescent light-bordered iron and mesh sculpture of India, reading “We the people of India reject CAA, NPR, NRC,” by Pawan Shukla, Birchandra (Veer), and Shaheen Bagh welders. Photo: Sarover Zaidi, 2020.

On Partitions

A normative rendering of the Partition of 1947 has been entrenched so deeply as an antagonism between one political, religious, or national constituency versus another that it is considered to be the unassailable historical narrative, based on “facts,” in which the violence of 1947 can be explained, rationalized, and periodized. Such a periodization allows for the years that follow to be simply declared as the period of “decolonization” that could unfold as if untainted, unaffected by the reproduction of a founding violence. Instead, we write of partitions in the plural, as a forceful concept that continues to divide and dispossess, and which endures in celebrated architecture and design projects to this day—for example, in a current international exhibition on modernist architecture in South Asia that uses the term “Decolonization” in its title.14 Decolonization needs to be restituted from rote historical narratives and static exhibitions and instead brought to the sites of ongoing struggle.

As Shaheen Bagh, a predominantly Muslim neighborhood in Delhi, became ground zero for a groundswell of protests in early 2020 against laws dividing the Indian citizenry (yet again) on the basis of religion, the violence of partitions erupted once more.15 The forty-foot structure of a people’s refusal to submit to this violence—an iron and mesh map of delineated, post-Independence India—alerts us to a landscape of coalescing histories that are simultaneously inflected by architectures of protest, ruptures of nation-states, and the hyperproduction of borders.

During the years that a modernist architectural sensibility crystallized around the world, camps in South Asia were shaping imagined and actualized nations: incubating Tibet in Karnataka’s Bylakuppe enclave; Bangladesh in settlements of stacked concrete pipe sections in Calcutta’s Salt Lake; or the Tamil Eelam in the Sri Lankan jungles. Their logic, that of “partition,” is one of apartheid, which gives architectural form to the present. Yet if the dissenters in Shaheen Bagh are right, then the subcontinent has inscribed not only lines of control but practices for their contestation and traversal. It is upon this legacy of partitions that an architectural futurity continues to hinge.

W.H. Auden, “Partition,” 1966.

While comparing partitions has been an ongoing scholarly exercise, we build our argument alongside two curatorial projects in art and architecture, which have gone beyond comparison, to explore form across geographies. They are Iftikhar Dadi and Hammad Nasar, eds., Lines of Control: Partition as a Productive Space (London: Green Cardamom; Ithaca: Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, 2012) and more recently, The Getty Research Institute, “The Art and Architecture of Partition and Confederation, Pakistan and Beyond,” research project and workshop organized by Maristella Casciato, Zirwat Chowdhury, and Farhan Karim, October 15–16, 2018. See also Decolonizing Art Architecture Art Residency (DAAR), Alessandro Petti, Sandi Hilal, Eyal Weizman, with Nicola Perugini, “A Common Assembly,” in Architecture after Revolution (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013).

The number 3 million is based on two separate Harvard studies that have been the most substantive exercises in grappling with the numbers question in relation to Partition. Prashant Bharadwaj, Asim Khwaja, and Atif Mian calculate that 3.7 million people went “missing” during the violence and most of them could be counted as those who died, in “The Partition of India: Demographic Consequences,” SSRN Electronic Journal (2009). Jennifer Leaning and colleagues estimate 2.3–3.2 million deaths in Punjab alone, in “The Demographic Impact of Partition in the Punjab in 1947,” Population Studies 62, no. 2 (2008): 155–170.

Reflections on incommensurability and the crisis of belonging follow from The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia (2007), and is also further explored in Vazira Zamindar, “Borderlanders: A Political Concept for Repair,” in Repair: Sustainable Design Futures, ed. Markus Berger and Kate Irvin (Routledge, 2022). Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) remains the most important for interrogations of statelessness beyond the juridical, and for an engagement with Arendt’s conception of statelessness for South Asia, see Vazira Zamindar, “Zarina’s Dark Roads: Exile, Statelessness and the Tenacity of Nostalgia,” Third Text Online, November 28, 2018, ➝.

Patrick French, “A New Way of Seeing Indian Independence and the Brutal ‘Great Migration’: Notes found in LIFE’s archives lend new depths of meaning to Margaret Bourke-White’s photos of the partition of India and Pakistan,” Time Magazine, August 14, 2016, ➝.

Vazira Zamindar, “Economies of Displacement,” in The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 79–157; Rotem Geva, “Scramble for Houses: Violence, A Fractionalized State, and Informal Economy in Post-Partition Delhi,” Modern Asian Studies 51, no. 3 (2017): 769–824. Ilyas Chattha, “Competitions for Resources: Partition’s Evacuee Property and the Sustenance of Corruption in Pakistan.” Modern Asian Studies 46, no. 5 (2012): 1182–1211.

Aamir Mufti, Enlightenment in the Colony: The Jewish Question and the Crisis of Postcolonial Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Faisal Devji, Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013).

Zamindar, The Long Partition, 29.

Quotations taken from Charles Correa, The New Landscape (Bombay: The Book Society of India, 1985), 15; “Manusha: Architecture as the measure of man,” in Vistāra: The Architecture of India, ed. Carmen Kagal (Bombay: The Festival of India, 1986), 30.

Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Building Histories: The Architectural and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern Delhi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Aditi Chandra, “Potential of the ‘Un-Exchangeable Monument’: Delhi’s Purana Qila, in the time of Partition, c.1947–63,” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 2, no. 1 (2013): 101–123; Nayanjot Lahiri, “Partitioning the Past: India’s Archaeological Heritage after Independence,” in Appropriating the Past: Philosophical Perspectives on the Practice of Archaeology, ed. Geoffrey Scarre and Robin Coningham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012): 295–311.

Suneetha Dasappa Kacker, “The DDA and the Idea of Delhi,” in The Idea of Delhi, ed. Romi Khosla (Mumbai: Marg, 2005), 68–77; Ravinder Kaur, Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi (Oxford University Press, 2007); on similarly “planning the nation” in West Bengal, see Uditi Sen, Citizen Refugee: Forging the Indian Nation After Partition, (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Farhan Karim, “Between Self and Citizenship: Doxiadis Associates in Postcolonial Pakistan 1958–68,” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 5, no. 1: 135–161; Ijlal Muzaffar, “Boundary Games: Ecochard, Doxiadis, and the Refugee Housing Projects under Military Rule in Pakistan, 1953–1959,” in Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century, ed. Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), 142–178. The authors are grateful to Balsam Abdul-Rahman of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library at the American University in Cairo and Giota Pavlidou of the Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives for contributions of invaluable knowledge to this research.

An expanded imagination of the “architectural archive” is greatly needed so that the material history of worlds such as those of housing societies is not limited to that found in archives of development. Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, “Architecture as a Form of Knowledge,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 40, no. 3 (2021). To this point, Fathy’s written notes on the housing study drawing demonstrate a disconnection from the lives of the Korangi refugees, even as they articulate a poetic resistance to the architectural standardization of housing: “How I wish if the planners treated their houses as leaves in the wind & studied those patterns that the choreographer of Autumn Leaves gave to his dancing formations {the optimum configuration}… Autumn Leaves, a ballet I have seen danced by the troupe of Pavlova to a waltz by Chopin. Zephyr (a man dancer in the Greek costume of Zephyr of the Tower of the Winds) is chasing the leaves— women dancers—blowing the wind onto them, and they are running here and there in front of him and at times they lie in patterns on the ground when he leaves them for a while… Assertion by Chauncey Wright: If the successive leaves of the fundamental spiral be placed at the particular azimuth which divides the circle in the “setio aurea”, then no leaves will ever be superposed;—{Ruskin’s vacant space}—and thus we are said to have “the most thorough and rapid distribution of the leaves round the stem, each new or higher leaf falling over the angular space between the two older ones which are nearest in direction, so as to divide it in the same ratio”… The story is told that Rykku, the Japanese master of the tea ceremony, instructed his son to clean the garden before the arrival of guests. Inspecting the immaculately finished result, he said to the youth, “This is not the way,” and shook a tree so that leaves fell in a free pattern across a path. Thus the man-made street rural order of the garden was formed with the natural order of living forms.” See Viola Bertini, “Working with Constantinos Doxiadis,” in Hassan Fathy: Earth & Utopia (London: Laurence King, 2018): 102–107.

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, Museum of Modern Art, 2022. For a restitutive approach to “decolonization,” see Shanti Jayewardene-Pillai, Geoffrey Manning Bawa: Decolonizing Architecture (Colombo: The National Trust Sri Lanka, 2017). The problem of “partitions” in the plural and across geographies is being taken up, moreover, in emerging studies: for example, Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi, “From Partitions,” in Architecture of Migration: The Dadaab Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Settlement (Durham: Duke University Press, forthcoming 2023); Safia Aidid, “Pan-Somali Dreams: Ethiopia, Greater Somalia, and the Somali Nationalist Imagination,” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 2020; Hollyamber Kennedy, “Infrastructures of ‘Legitimate Violence’: The Prussian Settlement Commission, Internal Colonization, and the Migrant Remainder,” Grey Room 76 (Summer 2019): 58–97.

Seema Mustafa, ed., Shaheen Bagh and the Idea of India: Writings on a Movement for Justice, Liberty and Equality (New Delhi: Speaking Tiger Books, 2020); Sarover Zaidi and Samprati Pani, “If on a winter’s night, azadi…” in Of Migration, ed. Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi and Rachel Lee (Canadian Centre for Architecture 2022), originally published on Chiragh Dilli (February 15, 2020); Chris Moffat, “#Afterlives: Shaheen Bagh and the Force of Foundation,” AllegraLab: Anthropology for Radical Optimism (May 2020).

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)