People have stopped visiting Los Angeles. They know if they wait long enough Los Angeles will come to them. So, watch for Los Angeles, appearing shortly in your neighborhood.

Denise Scott Brown arrived in Los Angeles to join the three-person faculty of UCLA’s newly established School of Architecture and Urban Planning in 1965. She included this statement above by an applicant to the program in her syllabus for the inaugural planning studio she taught in the Fall of 1966.1 The epigram proleptically offered a condensed formulation of Scott Brown’s aims for the course: to teach students that cities, even apparently formless ones like Los Angeles, were the physical manifestation of what she called “underlying forces” that could be made evident through close and penetrating observation but that could not be described in the traditional languages of architectural and urban theory and visualization. As the student anticipated, Scott Brown would argue over the course of the semester that an emerging city form was sneaking up on an unsuspecting audience sitting at home, an arrival to be witnessed like an event unfolding on the evening news. No mere metaphor, however, Los Angeles had in fact suddenly appeared on TV screens across the United States at the very moment Scott Brown arrived in the city. The Watts revolt, which began on August 11, 1965, triggered by the impact of “underlying forces”—covenanted neighborhoods and real estate policies, the divisive and segregating intrusion of freeways, and newly established systems of urban communications—was one of the first such events to be widely televised.2

Scott Brown came to Los Angeles to teach Urban Planning at a moment when the failures of urban planning were spectacularly on view.3 As a result, Scott Brown’s method of analytic observation, what she called “town watching,” is best understood as both a deliberately crafted research and pedagogical tool that she actively deployed in her studio and also as evidence of the largely passive and distanced way most inhabitants of the West side of Los Angeles witnessed the violent actualities unfolding across the East side of the city.4 This conjunction of unrelated phenomena—academic technique and televisual spectatorship—is one of many such meetings and overlaps that shaped her 1966 syllabus. She was a young, white, unmarried, South African woman, an academic trained in new approaches to urban planning informed by the social sciences, a recent arrival to a rapidly developing metropolitan form organized around loosely agglomerated sanctuaries that resisted conventional tools of analysis, and an untenured faculty member teaching for the first time in a public university undergirded by the consolidating forces of the just then dubbed “military, industrial, academic complex.”5 The impact of these markers of position ripple across virtually every one of the remarkable pages of Scott Brown’s teaching materials, defining the ways in which the “underlying forces” that determined city form were made visible by her work but also constituted an underlying force that produced the conditions of possibility of her own work as well.6

Denise Scott Brown, Urban Design 401, Form Forces and Functions in Santa Monica, UCLA, Syllabus, 1966.

While the fundamental features of Scott Brown’s biography are well established, how her biography shaped the relatively unknown work she did in Los Angeles and how that work shaped both her better-known work produced elsewhere and its complex reception warrants attention.7 Insofar as it has been studied, Los Angeles has been attended to as the place where the Scott Brown and Robert Venturi collaboration was cemented and from whence they launched their study of Las Vegas.8 However, Los Angeles was also where Scott Brown spent a unique period of time during which she was detached from the forms of determination that undergirded her before and after, an interlude between the structures of family and student life that had defined her conditions of possibility before 1965 and the requirements of professional and personal partnerships that structured her life after 1967. Her time in California unfolded during a hairpin turn in a long arc of migration that began in South Africa via the late nineteenth century pogroms in Latvia and Lithuania, followed a path established by the British Empire to London, paused in Philadelphia attracted to the presence of Louis Kahn, another Eastern European Jewish immigrant to the US, moved quickly through Birmingham, New Orleans, Houston, Phoenix, and Arcosanti, via Los Angeles to Berkeley, down to Los Angeles again, only to double back to Philadelphia in 1967, after a pitstop or two in Las Vegas.9 These spatio-temporal coordinates shed light not only on her biography but more importantly on the forms of authorship and intellection available to a Lithuanian/Latvian/South African/Jewish/woman/urban planner and architect during those years of both radical and yet unfulfilled possibility in American history.

Architecture operated for Scott Brown as a disciplinary Ellis Island, a structure of entry into the United States but also of assimilation into American liberal democratic culture. For Scott Brown, this process began in South Africa where she attended a grade school modeled on American progressive education: she still credits the Dewey method of “learning by doing” for her project-based pedagogy, driven by activities rather than by the transfer of traditional forms of knowledge, and for her interest in developing “scientific” methods rather than exercising moral judgement.10 The school was Christian: although South African Jews were less pressured to divest themselves of Jewish markers then they were elsewhere at the time, Jews were initially “united” with Christian Afrikaners both in their whiteness and in their shared resistance to British imperialism, particularly the British use of concentration camps as tools in their land appropriation campaigns against the Boers. By the time Scott Brown was a university student, however, the rise of Afrikaans nationalism and the arrival of a new generation of Jewish refugees put this unity into crisis: Apartheid linked the Jew and the black in a landscape of violence and trauma.11 At Witwatersrand, the resistance movement was strong, but it was also largely male. As a result, a student such as “Denise Lakofski” was entangled in a logic determining that to be Jewish was to be white, to be white was to be part of the apartheid state, to be “progressive” was to resist, but to be female was to be excluded from organized action.12

The very utopian claims of modern architecture that Scott Brown would come to critique made it appear, in 1952, to be a means of managing these incompatible identities. Its “promise” led Scott Brown away from Johannesburg and to London, where post-war reconstruction was in full optimistic swing and where figures such as Alison Smithson made it possible for women to imagine becoming architects who would help build a more just world.13 At the Architectural Association, Scott Brown discovered wide interest in architectural developments in the United States, particularly in Louis Kahn’s urban design proposals for Philadelphia. As a result, her final step of passage through architecture into American liberal democracy was the completion of her Urban Planning degree at the University of Pennsylvania. Her professors and mentors included men such as Herbert Gans, whose scholarly innovation was precisely to use “scientific” methods to unmark European immigrants and to argue that despite variations in taste, they too shared in America’s democratic values.14 By 1965, in fact, each of Scott Brown’s steps had rendered her markers of identity less and less legible: now married, she no longer had a Jewish name, did not look African to American eyes, and was even instructing architects to view women’s bodies, which is to say her body, through the lens of scientific disinterest.15 It must have seemed that architecture had successfully earned her a place among the American liberal arts.16

But of course, the deficiencies of American liberalism were also operative and the teaching appointment Scott Brown briefly held upon the completion of her degree among the all-male faculty at Penn was not renewed. As a result, she set off on a journey across the United States, spending long hours on the train town watching, listening to residents of Birmingham tell her that “what you read in the papers about us was exaggerated,” to isolated towns in what seemed to her an African desert “communicate,” and to students as they mobilized for free speech at Berkeley.17 She arrived in Los Angeles, unmarried, untenured, and untethered from any of the tribal identities that once might have both marked but also secured her.18 Her response was to immerse herself in her course preparations through which she sought to anchor her students and herself within a complete and total intellectual order, a goal she was well aware could not be reached but that she thought should be mustered with the “gaiety of despair.”19 The principal record of this effort was a syllabus that sought to construct an all-inclusive pedagogy that would provide a comprehensive explanatory mechanism for urban life.

Certain components of the course reflect the studio structure she developed at Penn, under the influence not only of Gans, but also of David Crane and William Wheaton: a cartographic understanding of urbanism, a sociological view of urban life, and a team-work approach to studio production.20 What changed when she taught in and about Los Angeles was the studio’s fullness and intensity, an amplitude derived not only from the syllabus’ extraordinary length but also from the course’s extensive interdisciplinarity, the large number of participants she included, and the array of techniques designed to capture comprehensive views of the city she presented to students. Where she had previously argued that urban form was legible to those reading underlying determinants, the number of these factors multiplied. Her courses had always been interdisciplinary, but the degree and range of engagement with other disciplines exploded across the academy. And field work modeled on what Gans called the participant/observer technique was not new to her teaching, but the field shifted from a single city block in Philadelphia to the entire region of Los Angeles, ranging from Disneyland to the beach, downtown, and much in between. In order to help her students “watch” this town, she gave countless lectures illustrated by slides, most of which she had taken herself, that show her stepping back from the focus on individuals and singularities seeking instead to encompass the widest possible angle of vision: taken from the air or a car, these images show freeways cutting through mountains and neighborhoods, houses precariously perched on canyon edges, and agricultural land paved over for parking lots.21 Challenged by the extreme and radically varied conditions of Los Angeles, what had been a nine-page syllabus when teaching at Penn became a one-hundred page total-design pedagogy.22

Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica was divided into sections including introduction, bibliography, studio organization, research on “definition and determinants of urban form,” and multiple design phases to develop creative suggestions “for emerging forces and forms.” Tellingly, Scott Brown felt Los Angles raised questions about urban rather than civic design, the term used at Penn, and she asked her students “What should an Urban Design Studio in Los Angeles be? What will become of our theories and philosophies as we match them against this urban extremity?”23 She focused the studio on Santa Monica because it contained these extremes, from topographical to class and race variation, and because the aviation and information industries had made their headquarters there. Santa Monica thus offered students both “a catalog of typical urban glories and pathologies” and also, particularly because of its growing minority populations, a prototype of future urban trends.24 She provided students with a history of Santa Monica she wrote herself from “discovery and settlement” in the sixteenth century to more recent but equally “aggressive” policies, especially the freeway completed just a few months before the start of the semester that had “ravaged the historic Negro settlement in Santa Monica.”25 She expected students to study land use patterns, legal frameworks, demography, economics, governmental forms, technologies, and transportation systems. Every one of the 132 class sessions had multiple readings, often guest lecturers, and detailed assignments. She instructed students to begin with various forms of data collection and in situ “town watching” (finding maps, “discriminately scanning” copious amounts of literature, and conducting interviews) and to conclude with “experimental graphic techniques” designed to move from specific data points to generalized problematics.26 While some of the assignments were rooted in the practices of urban sociology developed at Penn and MIT, she asked students to be attentive to whether or not forms of analysis like Kevin Lynch’s “categories for descripting perception and imageability” were useful in the Los Angeles of boulevards and freeways.27 Instead she encouraged students to “experiment with techniques and methods of drawing and photography which give some feeling of the multiplicity and complexity of patterns of activities and structures in the city and of their changes of intensity in space and time.”28

Scott Brown’s emphasis on the need for students to actively participate in the invention of new modes of urban representation was not merely a way for them to learn by doing but was itself a performance of Scott Brown’s theory of urbanism and of the planner. “The problem, and possibilities of cities are so wide and deep that it is impossible for one man to span them… We need specialists and their depth of knowledge: what we lack is connection.”29 She conceived of the studio, in other words, as she did an aerial photograph; she considered both tools for revealing epistemic nodes and for constituting connective tissues undergirding networks of disciplines and social groups. She drew an extraordinary number of specialists into this web; no fewer than thirty-eight people passed through the studio as jurors, guest lecturers, critics and resources. Some were old colleagues from Penn, such as Venturi, Crane, and Gans. Others were newer friends, such as the writer and critic Esther McCoy, Scott Brown’s neighbor and the only other woman in the group, and LA-based architects like Quincy Jones.30 Two categories of visitors were among the most consequential for the 1966 studio: one with expertise in representational developments within the architectural profession, and the other engaged in political discourses brought from other disciplines.

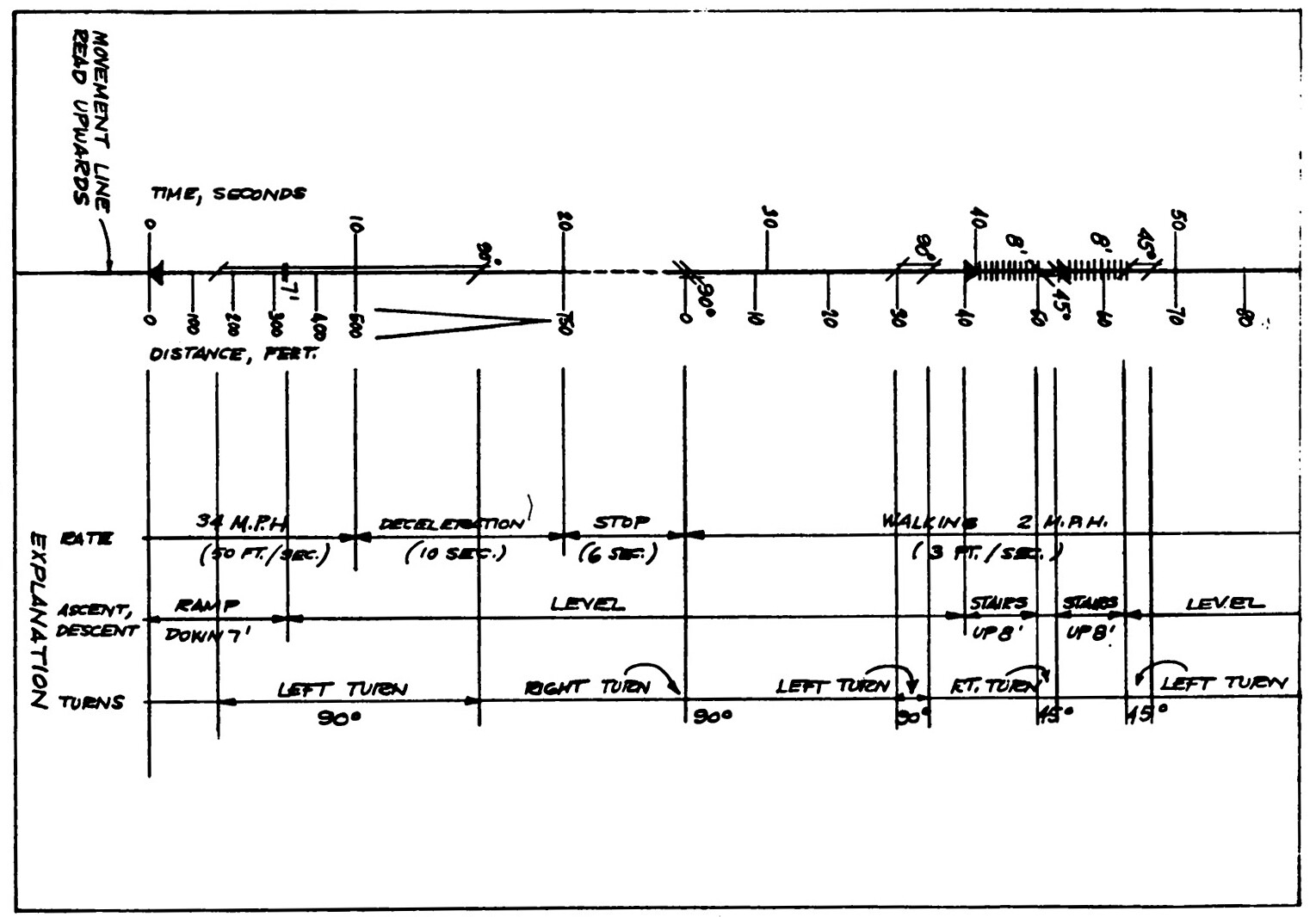

Philip Thiel, Movement Notation, 1961. Source: “A Sequence-Experience Notation for Architectural and Urban Spaces,” Town Planning Review 32, 1 (April 1961): 33–52. Originally published by Liverpool University Press. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

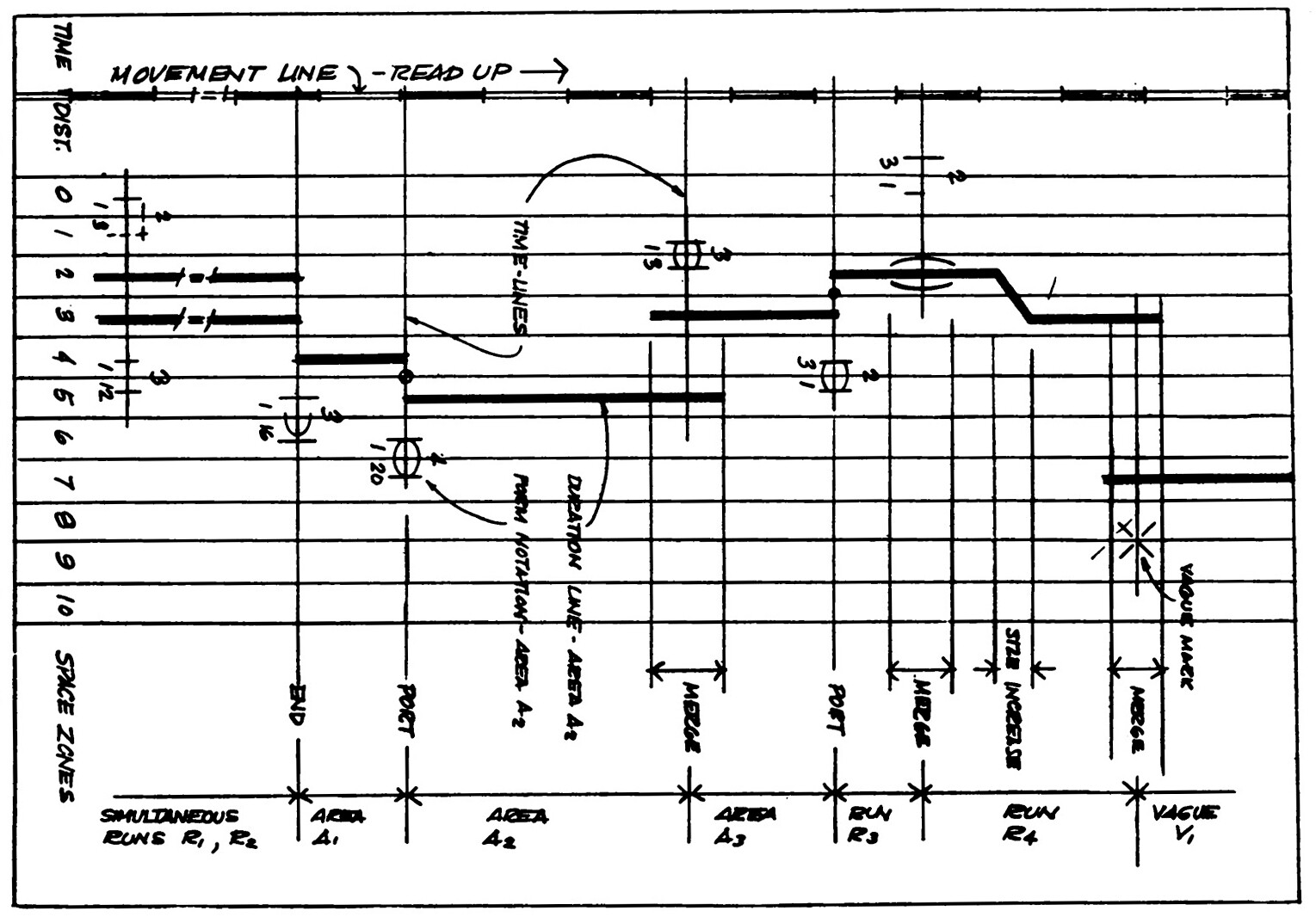

Philip Thiel, Duration Line and Space-Form Notation, 1961. Source: “A Sequence-Experience Notation for Architectural and Urban Spaces,” Town Planning Review 32, 1 (April 1961): 33–52. Originally published by Liverpool University Press. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

Philip Thiel, Movement Notation, 1961. Source: “A Sequence-Experience Notation for Architectural and Urban Spaces,” Town Planning Review 32, 1 (April 1961): 33–52. Originally published by Liverpool University Press. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

Visitors whose work focused on visual strategies included Philip Thiel and Peter Kamnitzer. Thiel, an architect who had spent a short time at Berkeley before taking an appointment in University of Washington, presented graphic techniques that incorporated elements learned while studying under Lynch and Gyorgy Kepes with notation forms used in dance to capture what he considered to be the time-based character of urban experience. Thiel argued that the rapid and dispersed urbanization of cities like Los Angeles had left designers “embarrassed by the lack of both a theory of form and of tools useful in representing the experience of form.”31 Acknowledging that the motion-picture might be such a tool but was still too costly, he offered instead a low-tech system “for the continuous representation of architectural and urban space-sequence experiences” that was “parametrically” adaptable to differences in the rate and direction of movement.32 While he described this technique as related to Sergei Eisenstein’s concept of vertical montage, he also argued that cities, unlike films, could not and should not control the attention of the audience as a film director did and therefore required representational tools that were not predetermined by a single director/planner. His manually calculable system for parametric notation was instead intended to privilege precisely a horizontal approach to urban planning.

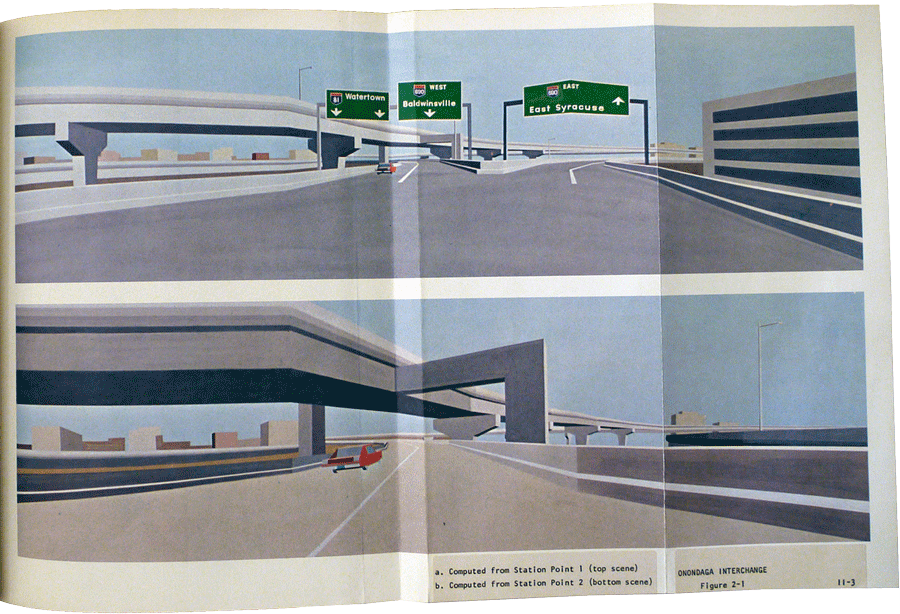

Peter Kamnitzer, Onandaga Freeway Interchange, 1969, book plate. Source: UCLA Library, Arts Library.

Peter Kamnitzer used radically different tools to pursue similar goals. A colleague of Scott Brown’s on the small UCLA faculty, Kamnitzer was then just starting work with NASA and GE on what would become “City-Scape,” a high-tech digital simulation of urban experience intended to enable planners creatively to manage the complexities of modern buildings and cities.33 Like Thiel and Scott Brown, Kamnitzer focused on the freeway as the principal means of, in this case digital, participatory “town watching,” deploying a “joystick” rather than camera or pencil as the user’s means of navigation. The goal was to enable planners, also conceived of as stand-ins for city-dwellers, to make real time decisions about urban mobility. Although they each worked through different visual media, Scott Brown, Thiel, and Kamnitzer all took students on simulated drives through the city, optimistically imagining that these new tools could “provoke the ‘next creative leap’” and “offer a new kind of planning process that may one day lead us … towards a truly participatory form of planning.”34

UCLA Institute for Transportation and Traffic Engineering, collision photograph, nd.

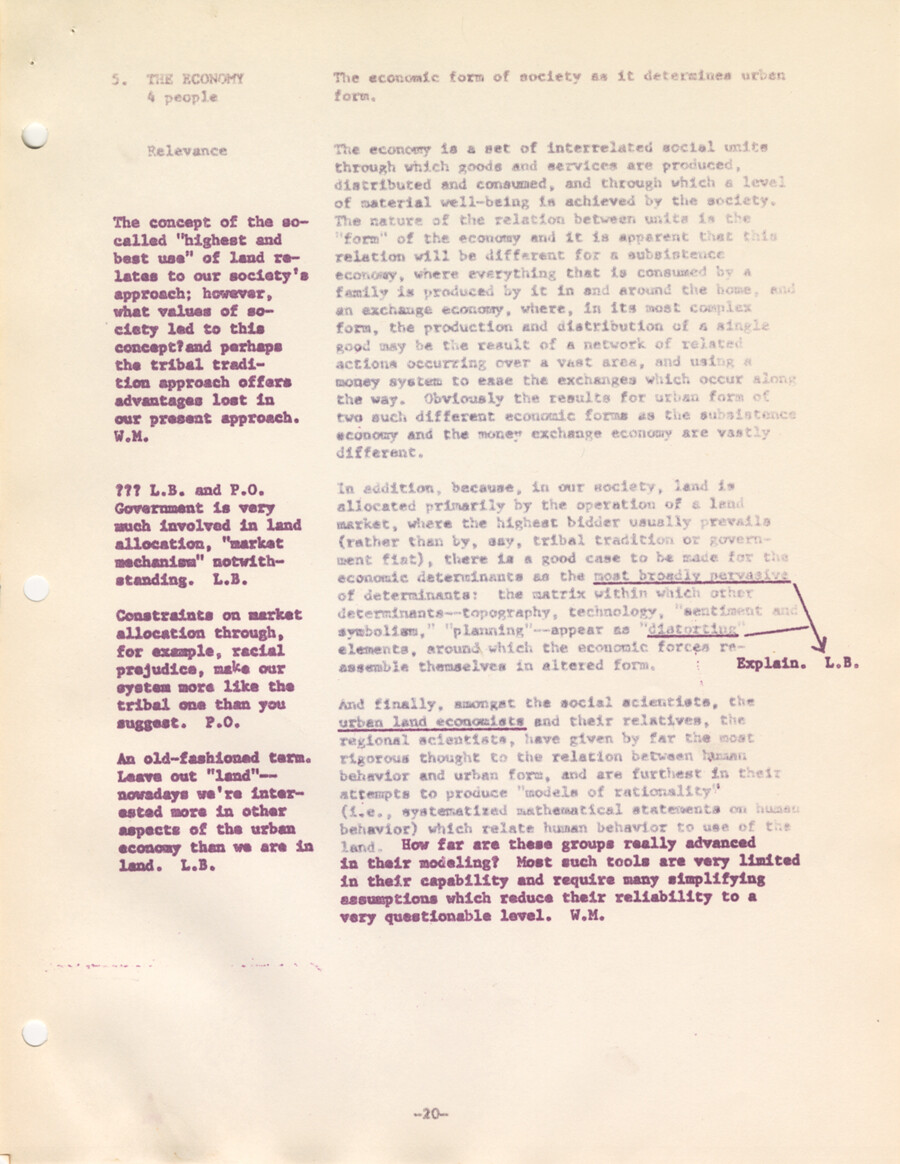

The second set of especially consequential participants in the studio were from other departments across the UCLA campus, including law, sociology and engineering. With them Scott Brown discussed a range of methodological rather than visual questions. For example, she asked sociologists for feedback on interview techniques, because, as she warned students, some interviewees would be understandably wary of urban planners having suffered at the hands of urban renewal and its “good intentions.” Eventually, treating the syllabus like a manuscript in a prepublication phase, she invited these colleagues to comment on the draft. William Mosher, a transportation engineer—who also focused on participatory planning and freeways, using photography to study the impact of movement and individual decision making in automotive safety—consistently prodded Scott Brown to further expand her point of view and to more explicitly address the politics of good intentions. He pressed her to avoid thinking regionally and to develop what he called a world view. He insisted that the scope of urban consideration should include issues of war, emancipation, and civil rights. He added notes on the growing importance of working mothers and the rights of women to urban planning, and on the problematic nature of planning for public happiness: “this is not necessarily achieved by elimination of public squalor. Some subgroups of society have NO desire to live in the manner those in power plan for. Classic examples are the attempts to change living habits of the American Indians and the attempt to change the living standards in our Appalachian Region.”35 The sociologist Peter Orleans was even more pointed about the need critically to examine the mechanisms controlling things like land use. He underscored that students should consider how “values expressed in physical form [are] constrained by existent opportunities,” and told Scott Brown that “constraints on market allocation through … racial prejudices make our system more like the tribal one than you suggest.”36 Given that Orleans co-edited the monumental volume Race, Change, and Urban Society just a few years later, it comes as no surprise that when Scott Brown instructed students to make comparative analyses of Century City and Santa Monica, Orleans asked, “how about Watts.”37

Denise Scott Brown, Urban Design 401, Form Forces and Functions in Santa Monica, UCLA, Syllabus, 1966. Source: Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

What is, however, surprising is that not only did Scott Brown solicit this robust feedback but that she included the most critical comments as marginalia in the final syllabus, making them extra visible with red ink. Her explicit goal in doing so was to avoid presenting “a spurious and dull unity” but it also implicitly transformed the syllabus itself into a demonstration of the multiplicity and complexity of patterns that she was seeking to present as constituting the city and the dialogic and participatory structure of good urban planning.38 Scott Brown kept her teaching materials in oxford Pressboard Report binders with metal prongs and multiple tabs, enabling her to add, delete and reorganize materials, and to ensure that the pedagogy was as plastic and performative as the city being taught. Students too were required to produce “reports” containing text and copious photographs and drawings in this same format and to submit them in fifty ditto copies. The studio’s entire output was, in effect, a collectively produced, polyvocal publication. Scott Brown’s course triggered an expansive debate, identified new channels of discourse, and relied on duplicative media as a mode of dissemination, making the studio output into a “little magazine” of the very kind she wrote about in one of her first published essays.39 Although her “book” on urban planning was largely written but did not find a publisher, what she could do in the Fall of 1966 was clip and ditto her Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica into provisional existence.40

What other existences were altered by Scott Brown’s year in Los Angeles may never be fully known because by 1967 she had returned to Pennsylvania, where the University was still committed to civic design and to a rapidly conventionalizing model of planning and its allied disciplines; to Philadelphia, a city that bore the imprint of an urban tradition alien to Los Angeles; and to married life rooted in both professional and personal partnerships. While this context opened new opportunities for Scott Brown, it also closed others in ways that make clear the specific constraints and possibilities in which she operated during her short but pivotal California sojourn of 1966. For example, the structural differences between her activities as co-author and informal publisher of Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica and those available to Venturi at the same historical moment are worth underscoring: Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture was also published in 1966, but with the support of MoMA, the Graham Foundation, the American Academy in Rome, and a host of assistants. Furthermore, elegantly understated in its self-referential and highly “authored” rhetoric, Complexity and Contradiction inserts Venturi’s work into a long lineage of famously heroic architects and attends almost exclusively to high culture despite his later interest in popular tastes.41 Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica, instead, is participatory and horizontal in its authorship, informal in its modes of production, self-critical, and polysemous in its engagement with different social groups and cultural forms. Finally, rather than cynically ironic or naively hopeful, what historians now commonly consider pervasive misjudgments made by architects during the 1960s, Scott Brown’s text is tinged with the gay despair of a woman with much to say and none of the institutional forms of support through which to say it.

Lack of certain kinds of opportunity is only one of the many historical forces that came together to shape Scott Brown’s work and that continue to shape its reception. In 1966, she did not receive approbation from Vincent Scully, who wrote the introduction to Complexity and Contradiction and became a key force both in maximizing Venturi’s claims to having become the seminal author of architectural postmodernism and in minimizing Scott Brown’s contribution to their collaboration for decades. Instead of their support, Scott Brown was harassed by many of her male colleagues, particularly during the time she spent in Los Angeles.42 On the one hand, while women are still harassed in the workplace, some have managed to use the institutional power that women like Scott Brown worked to generate in order to make sure that “Venturi” is never again used as a shorthand for their co-created work. On the other hand, some scholars have argued that because she was South African, she should have done more to address race and blackness in architecture.43 These revisions are welcome but also have important limitations. What Scott Brown did in 1966 does not live up to current standards of accountability for the racialized structure of the architectural academy and profession. For example, in a way that would be recognized as highly objectionable today, she appropriated the language of Martin Luther King when she changed the name of an assignment that had been “personal utopia” when teaching students in 1963 Philadelphia, to “I have a dream” when teaching in post-Watts revolt LA.44 Nevertheless, assessing this history of appropriation and indirection using only contemporary metrics anachronistically occludes the context informing the actions that were available to her and that she indeed took. Scott Brown made space for male colleagues, less vulnerable (if only by virtue of their gender) than she, to critique both the academy and the profession. She underscored Orleans’ explicit address to the racialization of urban planning in her syllabus and embedded the problem in her pedagogy. It is worth noting, in fact, that Orleans, the most outspoken of her colleagues about the failures of architectural design and planning, responded to the experience of collaborating with Scott Brown by deciding that the best way he could contribute to the question of race and urban society was to become an architect.45

It may, however, not be the critics but those with the very best intention of giving credit where credit is due who risk overwriting the most characteristic, and potentially still transformative, aspect of her work and working method. During this anomalously unfettered period of time, Scott Brown strove tirelessly to be collaborative and polyvocal, to engage critique and avoid what she feared was the intrinsic vanity of the single architect. She insisted that her students produce workmanlike drawings and avoid over-aestheticized design: “no false art,” she exclaimed.46 And she showed them how to do this by backing away from single objects beautifully represented in order to see the collective terrain in its often-grim reality, to town watch in ways that inevitably forced the abstraction of visual analysis to bump up against the violence of the nightly news. She was nothing if not workmanlike as the labor she invested in her teaching materials attests, and she used photography in a similarly workmanlike way. She recognized that her mode of operating through maps, detailed histories, and long conversations would appear to others as dull, particularly duller than the spectacular register of TV.47 She may not have anticipated, however, for how long these deliberately and necessarily unspectacular modes of operating would limit her own visibility to future historians of architecture still looking for spectacle and valuing only “influence.”

Although a handful of iconic photographs have been repeatedly extracted from the body of research that they constitute, they prove something self-evident; that Scott Brown was a woman cultivated by progressive education in the liberal arts who could use her well-trained eye to produce images dense with appeal to other similarly well-trained eyes. But this mutually affirming rapport overlooks the fact that, as an archive, her photographic corpus is largely made of an astonishing number of unformal images taken from a train, on a road, or in a plane; images that move away from framed views of things and that instead seek patterns within the messy overlap of human activity and the surface of the earth. These are images for and of research rather than display, evidence of Scott Brown’s commitment to studio as a collective knowledge producing instrument and of her investment in the broad view that gave rise to interdisciplinarity as a method and a value. Town watching was a strategy that inevitably entangled the passive academic observer with the violence televised on the evening news and actively risked the appeal of eidetic clarity and singularity in pursuit of comprehensiveness and participation. Though efforts to give credit are certainly overdue just as are calls for accountability, both risk pressing Scott Brown’s work into molds of authorship and artistic value that were simultaneously unavailable to her and that she worked hard to resist. New scrutiny reveals that aspects of her contributions do not meet today’s standards, but it also succumbs to ideological overdetermination when it ahistorically turns her into the type of heroic figure she chose not to be and that, given her positioning, she could not have been in 1966 Los Angeles.

There are copies of the syllabus for UCLA course 401, Fall, 1966, Form, Forces and Function in Santa Monica in the University archives at UCLA, Berkeley and in Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania. Only the latter is complete and associated with all of Scott Brown’s teaching materials for the course, including student work and a binder of letters evaluating the course, seemingly in support of a tenure review. This and all further citations will refer to the binder at Penn, which has not yet been fully incorporated into the finding aid but that I use courtesy of “The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania by the gift of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown.” Some sections of the binder are paginated and others are not. All references here will give section title and page number where possible. The anonymous student comment appears in UCLA 401, Introduction, p. 7. UCLA course 401 was an elaboration of courses Scott Brown had taught before at Penn and at Berkeley, and would teach again at Penn and Yale. The latter courses, and particularly the Las Vegas studio co-taught with Venturi, have been given wide attention: my focus here will be on what was unique to UCLA course 401 (1966). George Dudley was made dean of UCLA’s new program in 1964. The other two full-time faculty were Peter Kamnitzer and Henry C.K. Liu. (For more on Kamnitzer, see below. Liu, born in Hong Kong and educated at Harvard, was working on regional development while at UCLA but does appear to have had much substantive interaction with Scott Brown). Additional part-time instructors and lecturers were drawn from professionals working Los Angles and from other departments in the University. On the Vegas Studio, see, Las Vegas Studio: Images From the Archive of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, edited by Hilar Stadler and Martino Stierli in collaboration with Peter Fischli (Zurich: Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess Ag, 2008); Aron Vinegar, I Am a Monument: On Learning From Las Vegas (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008); Aron Vinegar and Michael J. Golec, Relearning From Las Vegas (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Martino Stierli, Las Vegas In the Rearview Mirror: the City In Theory, Photography, and Film (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2013).

See Elizabeth Wheeler, “More Than the Western Sky: Watts on Television, August 1965.” Journal of Film and Video, 54, 2/3 (2002): 11–26. On the role of TV in the coverage of the race revolts in Philadelphia and the Guild House, designed by Venturi, before Scott Brown joined the firm, see my “Oh My Aching Antenna: The Fall and Rise of Postmodern Creativity,” Log 37, The Architectural Imagination United States Pavilion (Spring/Summer 2016): 214–227.

Scott Brown wrote a series of letters to “friends and family” documenting her journey to the West coast and while at Berkeley. In one, dated August 21, 1965, she wrote “early in September, I shall be moving to Los Angeles and hope to start work there soon after.” She began teaching at UCLA in the Fall of 1966. These letters are reproduced in my Everything Loose Will Land: 1970s Art and Architecture In Los Angeles (Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg: New York, NY, 2013), 82–90. These letters also include descriptions of her first visits to Las Vegas.

“Town watching” first appears on page 5 of UCLA 401, “Introduction,” but reappears throughout.

Scott Brown describes Los Angeles as in the process of “nucleating,” a condition of multi-centeredness that Bernard Tschumi, just a few years later and working with similar planning documents but using them to produce a radically more overt political critique, described as organized around bounded sanctuaries. See his “Sanctuaries,” Architectural Design 43, 9 (1973): 575–590. This quality made Los Angeles the primary exemplar of post-metropolitan urbanism and eventually the shared focus of the so-called postmodern geographers, many of whom, like Edward Soja, also taught at UCLA. Scott Brown’s remarks about LA are part of a section entitled City of Change, in UCLA 401, “Phase III, Part A,” 9. Scott Brown was particularly interested in why Douglas Aircraft and the Rand corporation chose Santa Monica for their HQs. On the military complex see Stuart W. Leslie, The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to underscore the multiple forms of inequality that operate simultaneously in determining the conditions of possibility for women of color, including the experience of their own identity. Because the conditioning factors of race, immigration status, gender and class that shaped Scott Brown’s possibilities in 1965–1966 were not all rooted in oppression and discrimination, I use positionality as the better term for situating her within her historical context. See Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, “Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color,” Stanford Law Review 43, 6 (July 1991): 1241–1299.

Scott Brown has given many interviews on her personal and intellectual history in which she describes her appreciation for Santa Monica, particularly the beach culture and because she and Venturi were married at her Ocean Park home. She has not written about her time at UCLA in particular. While her interviews are scattered among a wide variety of publications and websites, the best source for her account of herself is her collected essays, Having Words (London: Architectural Association, 2009).

Although disentangling their respective contributions to what eventually became a lifetime of collaboration is futile, it does seem to be the case that Venturi’s interest in popular culture and Americana grew stronger once they started to work together. Similarly, although they both recognized that contemporary communication systems were transforming American society and architecture, his interest in the early 1960s was more metaphorical where hers was more operational. For example, while presenting the Guild House in a lecture to students at Yale, he described the windows of the rear elevation as like an IBM punch card while Scott Brown described the illuminated signs of small towns in the desert as acts of communication: “Then there were the towns. All you notice is a series of bright billboards, neon signs & TV antennae… The buildings are nondescript, sunk into the landscape. The towns appear, then as nothing other than communication.” “Letter to Friends, April 26, 1965,” in Everything Loose Will Land, 88. On Venturi’s lecture at Yale, see my Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernization Effects, Montréal (Québec: Canadian Centre for Architecture; Leipzig, Germany: Spector Books, 2020), 95–99.

The details of this itinerary can be reconstructed through her letters, cited above.

Some of the following discussed is based on two extensive interviews I conducted with Scott Brown on July 24 and August 14, 2021. Ayala Levin’s essay on Scott Brown and the southern settler-colonial conditions that shaped her views of architecture in the United States appeared after this essay was in press. See Ayala Levin, “Learning from Johannesburg: Unpacking Denise Scott Brown’s South African View of Las Vegas,” in Writing Architectural History: Evidence and Narrative in the Twenty-First Century, Aggregate eds., (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021), 235–248.

On South Africa, see Saul Dubow, A Commonwealth of Knowledge: Science, Sensibility, and White South Africe, 1820-2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Gideon Shimoni, “South African Jews and the Apartheid Crisis.” The American Jewish Year Book 88 (1988): 3–58; Andrew Caplan, South African Jews in London (Capetown: University of London, 2011). See also Andrew Caplan, South African Jews in London (Capetown: University of London, 2011), and Ayala Levin “South African ‘know-how’ and Israeli ‘facts of life’: the Planning of Afridar, Ashkelon, 1949–1956,” Planning Perspectives 34, 2 (2019): 285–309. On Witwatersrand, see Mervyn Shear, WITS: A University in the Apartheid Era (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1996), and Bruce K. Murray, “Wits, the ‘Open Years: a History of the University of Witwatersrand, 1939–1959” (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand Press, 1997).

When I asked directly if she had participated in the resistance movement while a university student and if not why, Scott Brown stated, “I was afraid.”

Scott Brown now describes her early interest in architecture as generated by her desire to participate in “building a just South Africa.” This specific vocabulary, now a common descriptor of anti-Apartheid goals and used by Scott Brown in Having Words, for example, is, as far as I have been able to determine, an ex post facto turn of phrase with respect to her move to London. As is well known, the interest in American pop culture was widespread among English architects at the time, and was particularly strong among the Independent Group and their circle, which of course included the Smithsons and Reyner Banham.

See David R. Roediger, Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs (New York: Basic Books, 2005). Gans eventually discussed this issue in his own work. See Herbert J. Gans, “Racialization and Racialization Research,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, 3 (2017), 341–352. For introductions to planning history and to the history of architectural pedagogy, see The Profession of City Planning: Changes, Images, and Challenges, 1950–2000, ed. Lloyd Rodwin and Bishwapriya Sanyal (New Brunswick: Center for Urban Policy Research and Rutgers University Press, 2000), and Joan Ockman and Rebecca Williamson, Architecture School: Three Centuries of Educating Architects in North America (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press, 2012).

In her essay “Planning the Powder Room,” published in 1967 but conceived earlier, Scott Brown acknowledges that the design of women’s restrooms is a “delicate” subject requiring the “delicacy of a lady.” However, and despite the fact that the essay was written in order to invite men to look into such spaces, she assumes what she calls the position of an “unrecalcitrant functionalist of the1930s type,” a type known to be deliberately gender neutral. The essay is republished in Having Words, 128–135. Scott Brown, who had married Robert Scott Brown in 1955, was suddenly widowed when he was killed in a car accident in 1959. The unimaginable trauma of this event was be exacerbated by the way becoming unmarried increasingly made her a target of sexual harassment by her colleagues. This appears to have been especially the case in Los Angeles, where few of her colleagues had known her during the first years of her grief and mourning.

For her own account of the role of art education in her journey as an immigrant, see her “Invention and Tradition in the Making of American Place” (1986) reprinted in Having Words, 5–21.

Although her language is typically oblique, I assume that in a letter, written Jan. 31, 1965, she is referring to comments made to her by white architects in Birmingham (she mostly met and was given tours by local architects somehow or other connected to Penn) about the Birmingham confrontation of 1963, part of her repeated rediscovery of apartheid by another name in the United States. For the letter, see Everything Loose Will Land, 83.

Scott Brown often discusses tribal identity as it shaped her childhood in South Africa. Peter Orleans also cites her use of this term. See below.

She describes the studio task as certainly impossible and as such requiring a sense of adventure, courage and “gaiety of despair.” UCLA 401, Phase II, 41.

There is of course a substantial literature on the history of urban planning: here I mention only Eric Mumford, Defining Urban Design: CIAM Architects and the Formation of a Discipline, 1937–69 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009); Carola Hein, The Routledge Handbook of Planning History (New York: Routledge, 2018); Companion to Urban Design, Tridib Banerjee and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, eds. (New York and London: Routledge, 2011). Gerald D. Jaynes, David E. Apter, Herbert J. Gans, William Kornblum, Ruth Horowitz, James F. Short, Gerald D. Suttles, Robert E. Washington, “The Chicago school and the roots of urban ethnography: An intergenerational conversation with Gerald D. Jaynes, David E. Apter, Herbert J. Gans, William Kornblum, Ruth Horowitz, James F. Short, Jr, Gerald D. Suttles and Robert E. Washington,” Ethnography 10, 4 (2009), 375–396. As she moved farther from Penn, Scott Brown’s vocabulary shifted. Not only did she reject the term “civic design” that was used at Penn, but her terms for describing the structure and nature of teamwork also shifted. For example, at Penn, she gave some students the role of “captains” and others “scribes,” and defined the overall system as “a limited democracy.” This language of hierarchical labor is eliminated in the UCLA syllabus in favor of more neutral terms such as “organizer.” See UCLA 401, “Studio Organization,” 1–3. See also the syllabus for CP503, 7, taught at Penn in 1963.

These images are the visual analog to her definition of the planner as the person who is “disillusioned with the single architect working on a single lot,” and who endeavors “to overcome our tendency, as architects, to concern ourselves with the isolated building.” See CP503, 3, and UCLA 401, “II,” 51.

In fact, some of her visitors found her dogged pursuit of comprehensiveness too much. Leland S. Burns, for example, who would become one of the most influential scholars of modern housing economics and housing policy and would eventually join the UCLA Planning faculty in 1968, wrote a tongue in cheek “review” of her course that calculated intellectual output and exhaustion over the course of a day of juries, complete with a chart of the entropic loss of focus. He wrote “By means of a very clever decide, concealed on my person yesterday, I was able to make some rather precise estimate of my ‘phase-out rate’ and ‘productivity rate,’ … and have plotted the results on the attached graph… I recommend holding each presentation to a fixed time period, rigorously enforced (perhaps with a timer equipped with frightening alarm.) It seems to me that this sort of discipline is part of training for the professional world as well.” See letter to Prof. Denise Scott Brown from Lee Burns, Nov. 10, 1966, in UCLA 401, Supportive Material.

UCLA 401, Introduction, p. 7.

See UCLA 401, Item E, part I, October 3, 1966, “Outline: Introduction to Santa Monica”, 2.

See UCLA 401, Item E, part I, October 3, 1966, “Outline: Introduction to Santa Monica,” 6.

See UCLA 401, Phase I “The Definition of Urban Form,” 2.

See UCLA 401, Phase I “The Definition of Urban Form,” 4.

See UCLA 401, Phase I “The Definition of Urban Form,” 10.

See UCLA 401, “Introduction,” 5. This definition is not unique to the UCLA syllabus and appears in her most of her teaching materials from 1963 on.

Although neighbors, friends, and colleagues, and although Scott Brown later wrote of their friendship in positive terms, they had a falling out. McCoy wrote a biting letter to Scott Brown in response to Scott Brown’s essay about her. Not only did McCoy feel that Scott Brown had falsely represented her as financially dependent on men for money, but McCoy was deeply upset that Scott Brown, just like the men on the UCLA faculty, had not valued McCoy’s work: McCoy wrote that she discovered “soon after we met that you had not read any of my three published books and had no comments on my writing on architecture for American and Italian journals.” See the letter from McCoy to Scott Brown, Feb. 6,1989, Box 14, Folder 4: Denise Scott Brown, “Knowing Esther McCoy,” in “Esther McCoy papers,” Archives of American Art. On McCoy, see Sympathetic Seeing: Esther Mccoy and The Heart of American Modernist Architecture and Design,” Kimberli Meyer and Susan Morgan, eds. (Nürnberg: MAK Center for Art and Architecture and Verlag für Moderne Kunst, 2011).

See Philip Thiel, “An Experiment in Space Notation,” The Architectural Review (May 1, 1962): 131, 783, and his “A Sequence-Experience Notation for Architectural and Urban Spaces,” The Town Planning Review 32, 1 (April 1961): 33–52. Thiel would eventually also publish Visual Awareness and Design: an Introductory Program In Conceptual Awareness, Perceptual Sensitivity, and Basic Design Skills (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981), and People, Paths, and Purposes: Notations for a Participatory Envirotecture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997).

See “A Sequence-Experience Notation,” 34 and 50.

On Kamnitzer, see Curtis Roth, “Software Epigenetics and Architectures of Life,” Becoming Digital (e-flux Architecture, 2019), ➝; Nicholas de Monchaux, Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); and my Everything Loose Will Land, 309.

Kamnitzer, “Computer Aid to Design,” AD 9 (1969): 508.

See UCLA 401, Phase, II, “Determinants of Urban Form,” Oct. 17, 1966, 26. See also the following note Mosher added: “Perhaps a resurgence of dwelling in the central city could occur if the needs of the ‘modern’ family were provided for in parks, recreation, child care, privacy etc. This relates to the large influx of ‘mothers’ into the working force.” UCLA 401, Phase, II. 14.

See UCLA 401, Phase, II, “Determinants of Urban Form,” Oct. 17, 1966, 9, his emphasis, and 20.

UCLA 401, Phase, II., “Determinants of Urban Form,” Oct. 17, 1966, 24. See also, Peter Orleans and William Russell Ellis, Race, Change, and Urban Society (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1971). It must be noted that most of the photographs taken by Scott Brown in Watts focus on the Watts Tower and not on the neighborhood in general.

UCLA 401, Phase, II, “Determinants of Urban Form,” Oct. 17, 1966, 6.

See Scott Brown, “Little Magazines in Architecture and Urbanism,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 34, 4 (1968): 223–233.

Departmental records from the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at UCLA contain some material related to Scott Brown’s tenure and promotion case that refer to a manuscript. On alternative publications during this period, see Beatriz Colomina, Craig Buckley, and Urtzi Grau, Clip, Stamp, Fold: the Radical Architecture of Little Magazines, 196x to 197x (Barcelona: Actar, 2010), and Craig Buckley, Graphic Assembly: Montage, Media, and Experimental Architecture In the 1960s (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

On Venturi and historical privilege, see Jonathan Massey, “Review: Power and Privilege,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 497-498.

During my interview with Scott Brown she carefully and with great detail described the almost constant assault she was under while at UCLA from most of her male colleagues, including her Dean, senior colleagues from other Departments, as well as the members of her own faculty.

See for example, Rebecca Choi, “Black Architectures: Race, Pedagogy and practice, 1957-1966,” UCLA dissertation, 2020. For recent discussions of race and its embeddedness in modern architecture see Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson, Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2020), and Charles L. Davis, Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2019).

UCLA 401, Phase III Part A, 13.

Although Orleans was an associate professor at UCLA, he left his position to pursue an architecture degree at the University of Colorado, Denver.

In describing the format of student reports, she wrote “this will take two forms, a written-and-illustrated report and a verbal, slide-and-magic-lantern illustrated group lecture… It should be in Ditto form and illustrated copiously by photographs or drawings or both… Drawings should be workman-like affairs designed to inform not evade—no false ‘art.’ The same with the photographs.” UCLA 401, Phase III Part A, 40. This requirement and description were consistent across all her teaching at Penn, Berkeley and UCLA.

The “dullness” of the materials needed by the urban planner to non-planners in general and architects in particular, is something she mentions frequently. To give just one example, she wrote in the introduction to the studio: “if he {the urban designer} continues to find the world of the sociologist ‘very dull’… if the joy of numbers and their uncertainty, or the mechanics of the decision-making processes … remain foreign to him; if he believes ecology is to do only with plants and flowers, and climate is something we have to overcome with mechanical systems; then I’m afraid he is the only who is stuffy and dull,” her emphasis. UCLA 401, Introduction, 4.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Subject

This essay was originally written for Frida Grahn ed., Denise Scott Brown In Other Eyes: Portraits of an Architect (Birkhäuser, 2022).

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)