Nick Axel Your work has always engaged with the dialectic between the abstract and the concrete, the virtual and the actual. In a lot of your early work, for instance, you would reference and translate historical symbols and cultural icons into digital environments; if you are talking about columns, or structure, or support, you would model and render an Ionic column. But in a series of more recent works, you introduce a certain abstractness of form. Post-Ruin (Pink) (2019) and Polemos (2017) are both installations comprised of large geometrical foam blocks designed in such a way that they can be assembled, in gestalt-like fashion, into a larger shape, such as a tank or a phallus, but they also don’t need to be. What brought you to work with geometrical abstraction in this way?

Andreas Angelidakis I’m interested in the idea of contradiction. I see the fact that these installations can be assembled into iconic shapes, but that anybody can change them into something else, as a kind of end of design. Even if all the pieces are just left on the floor, not touching each other, it’s still the same project. This lineage of projects goes back to my early internet experiments, where I picked forms out of object libraries and did different things with them in open worlds like Second Life. Soft Ruin (2006) was the first of these, in which I simply tried to make a ruin online. I tried to make something fall apart, to have the quality of a ruin that buildings in these virtual worlds never seemed to have. Online buildings don’t grow old. If you look at them ten years later, they’re just sort of lame.

NA The interface ages, but not the things within.

AA Exactly. It stays identical, but the interface looks dated, and not old in a way that can be more conventionally appreciated. So with Soft Ruin, I made a ruined building online, in Second Life, and then made a copy of that building in soft foam, with reference to early postmodern Gufram furniture.

NA ActiveWorlds and Second Life, which is where some of your earliest work took place, are open world games. They’re inherently interactive. Your body of work as a whole has largely been the result of interacting with ruins in all different kinds of ways, profaning them. But now it seems that you’re giving this ability to a wider audience, to the public.

AA The first time that I convinced the museum to let the audience do whatever they wanted with my work was in Istanbul, in a show that Mari Spirito curated at ALT Art Space. And people went crazy. I guess we’re all so used to not touching anything in a museum, being careful, and being quiet. But suddenly when there’s a room where you can do whatever you want… When Polemos was installed at documenta 14 in Kassel, even though it was not meant to be demolished every day, people attacked it. The guards called me asking what they were supposed to do? But I’m interested in letting go of this idea that the designer makes something that is supposed to stay the way it was designed. Twenty years ago, if you were to ask students for a photograph of a flower, they would go out and with a camera and look for flowers to photograph. But today, we just Google “flower.”

Andreas Angelidakis, Polemos, documenta 14, 2017. Photo: Nils Klinger.

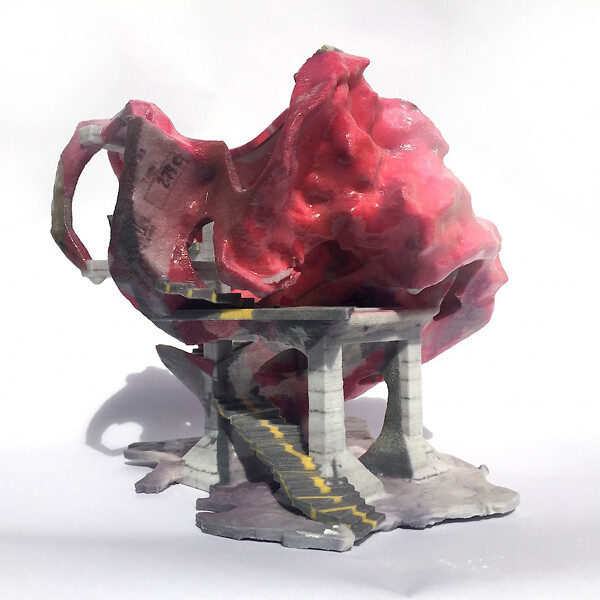

NA How does this relate to your longstanding practice of working with 3D printers and creating these weird digital hybrid sculptures?

AA The 3D prints started as a result of losing a series of designs in ActiveWorlds because somebody stopped paying the hosting server. So I thought, next time, I’m going to try to make them physical, to have some kind of hardcopy backup. That was in the early 2000s, when the first 3D printing companies were offering free prints. They were trying to advertise 3D printing, so you could just send them a file and they would send you back a print for free. I was calling them “Ghosts” because they were monochrome; they were white copies of online buildings. But now I continue to work in this way because I like the immediacy. I like the idea that you can just make something without any sort of in-between, which is also my problem with architecture.

Nikolaus Hirsch As a case of a highly unstable urban environment, Athens has been very influential to your work. How do you see the idea of immediacy that you use to describe your sculptures in your reading of cities?

AA Buildings are not just designed and realized, but are the result of so many outside forces. In the case of Athens, things like migration, geopolitics, financial regimes, and governmental corruption shaped the city. The city looks chaotic because it was. Everybody had a little piece of land, and everyone tried to squeeze by legislations and make their buildings as cheap possible. The result is something not resolved as design, but very active.

NH So Athens is the result of immediate and spontaneous planning processes?

AA Yes. And it builds up like a ruin. It’s also something continuous. If you don’t visit Athens for five years, you’ll see things that you wouldn’t expect, that aren’t part of a design. It’s not like a Paris, which is a very resolved city, with a rather clear identity. But in Athens, things happen, and only then it becomes a part of its design.

Andreas Angelidakis, Endless Garbage Bag House, 2015.

NA How do you situate your work in relationship to Athens?

AA That’s tricky. A work like Post-Ruin comes from combining my internet research with research into Athens, but I wouldn’t say it’s an Athenian work per se. It draws from the way Athens relates to ruins, as things that don’t need to be taken very seriously and can be used in whatever way. But this, and the part of my work that deals with ruins in an almost cynical way, could also relate to Rome or other cities that have ruins, or even Europe as a kind of crumbling ruin that people can and should do whatever they want with it.

NA Some of your sculptures have a libidinal quality to them. There’s a certain animism of form, where by reading and interpreting Athenian typologies such as the polykatikia, you create sculptures of buildings trying, in a sense, to become what it wants to be. Would you say that you are channeling the subconscious of the city, analyzing it, bringing out it’s traumas, it’s demons, it’s perverse desires?

AA Sure, but it’s also personal. They are like avatars. A lot of times I use buildings as actors to express what I am feeling, so I look for qualities in the built environment that allow me to speak.

NA So it’s not necessarily the city that you are analyzing, but that these sculptures are a vehicle for your own psychological process?

AA But the two are related. In 2010, for instance, I had a lot of personal dramas, but at the same time, the financial crisis was happening. So I did a lot of projects that seemed to be talking about the Greek crisis, but in fact were not. I used the Greek crisis as a paravent, or a puppet. This is also a way of letting go of control; people can say or do whatever they want with the sculptures, but it’s still going to be there.

NH It reminds me of Aldo Rossi´s idea of the monument, where the ruin is something that stays, but always has the potential to be changed and appropriated. Think of the Colosseum in Rome, which in the nineteenth century was full of small shops because the building became far too big for the very small city that Rome was at the time.

AA I’m very interested in that early moment of postmodernism, before it became a style, because at that moment architecture had the potential to become a critical tool. The early postmodernists, like Rossi and Ettore Sottsass, were criticizing consumption and architecture. The critical aspect got lost when it became equated with columns and arches. But I like the idea of starchitecture buildings assuming different poses with twisting columns and jutting balconies. It’s a ridiculous puppet of our time.

NA It’s almost like some of these traumas that you have exorcized from yourself have found their place around the world in different parts of cities.

AA Earlier this year I opened a show in Athens at The Breeder gallery where the sculptures assume the different types of poses that starchitecture buildings do. They’re covered in graffiti from random texts that I picked up, everything from Keller Easterling to Instagram ads, like “A Submissive Acknowledgement of Powerlessness,” or “Simple tricks to look better in a photo.” They’re contradictions; buildings that actually make fun of or are cynical about themselves. I may be becoming older and more bitter, but I’ve also decided to enjoy that.

NA It seems that’s coming with a certain playfulness, and maybe an opening up of this kind cynicism as a collective act of joy. How do you value all of the different quotations or references you employ in your work?

AA I have a certain set of references that I tend to use. But the Maison Dom-Ino comes from my childhood, where I would look at all of the unfinished buildings in Athens. I thought they were toys, that I could play with their bricks. It’s the template for anything. What I like is that it can become anything, and I feel that freedom is missing from architecture, from myself.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

This conversation took place as part of the talks program of Design Miami/ Basel 2019.

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)