Nikolaus Hirsch You recently won a competition to build a new hospital in Tambacounda, Senegal. A project like this can be thought about as a product, the kind of finished or polished architecture that could be published in glossy magazines, but it’s the process, and the role of the architect within it, that is perhaps more interesting here. What is your relationship to the local? Or asked differently, what is the local here?

Manuel Herz The best way to address your question of the local is to start with an anecdote of how the project actually came about. I got an email with an invitation to participate in a competition for a project in eastern Senegal that was being funded by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. I thought about it and, after a while, I wrote a response declining the invitation, because I did not think it was correct for ten architects from Western centers like Basel, Berlin, London, New York, and Paris to invent a “solution” for a region that they have never visited, for doctors that they’ve never spoken to, for patients that they have never met, and for a kind of a craft and a climate that they don’t know. I added to this that I would have preferred a more collaborative process of developing the project, rather than a competition. Two hours later, I received a telephone call saying that my response hit a nerve at the foundation and showed them that were on the wrong track. They asked to meet, and out of this eventually came a commission. So if you ask about the local, it’s really a question about how projects are approached from afar. And for that, a different type of process is necessary.

Nick Axel There is a contradiction to the idea of humanitarian architecture. Is it resigned to be the lesser evil? What are some of the ways that you addressed the tension of being a Basel-based architect who is creating a new space in a new hospital in Senegal?

MH First of all, we didn’t start by designing. We started with research. We went there with a team for maybe two or three weeks to investigate the region and spend time with the doctors, trying to understand what they really need and what they want, what the climate is like there, what the flora and fauna are… Then we underwent a collaborative design process. This isn’t to say that the doctors were actually doing the design, but we were working together to figure out what works and what doesn’t work for them. We didn’t bring a ready-made solution from the outside, but rather initiated a process whereby a design emerged from conversation. This kind of interaction with the local context did not only take place in the beginning but has played out throughout the whole process; planning, application, funding, and construction all became much richer than in a conventional project.

NH I wonder how we can understand the organization of that process. Did you have a local partner? Architecture is a practice that is based on a very particular distribution of labor, and there are many more people involved than just the architect, despite the fact that the architect might be credited as its “author.” An architect is unable to work on his or her own.

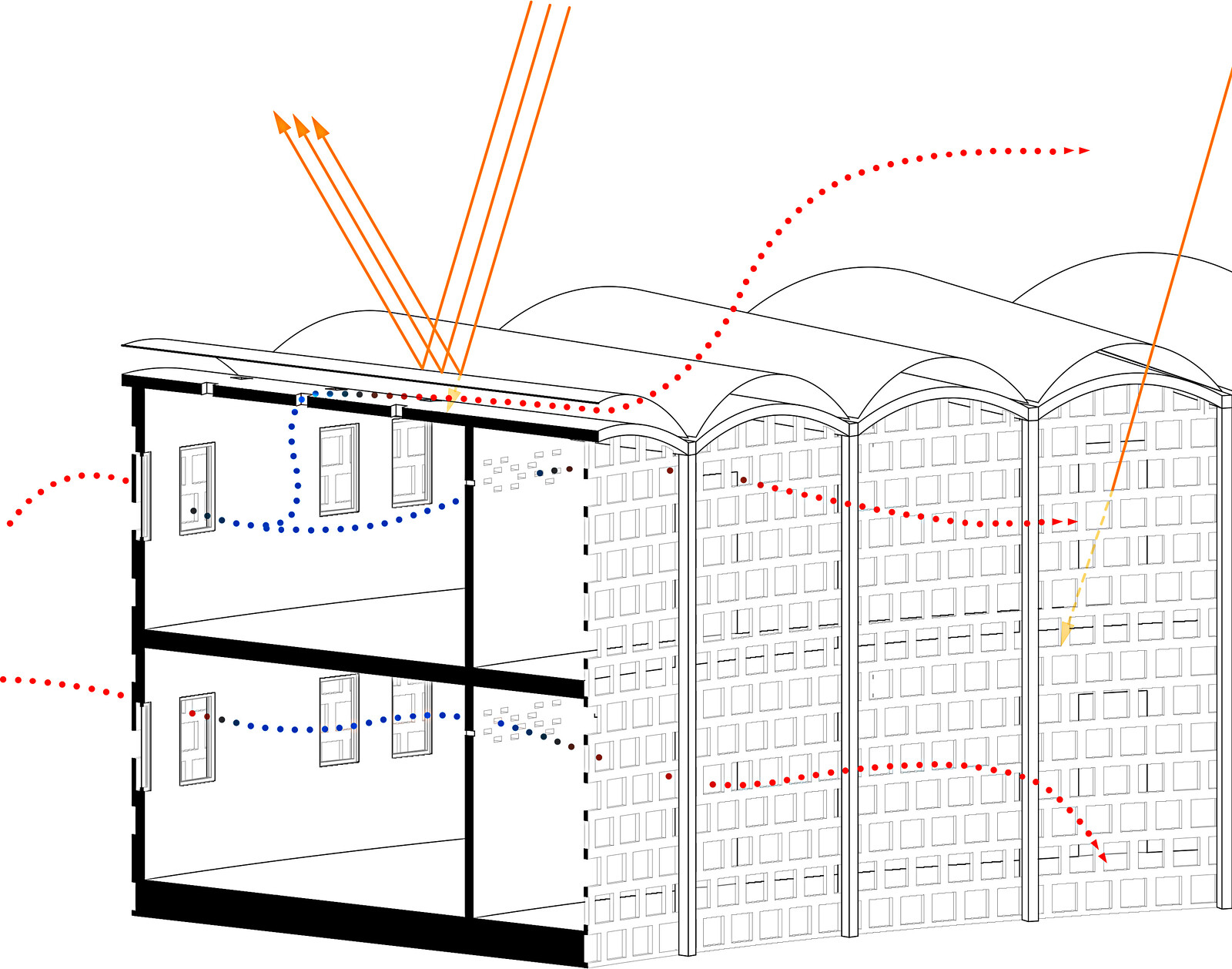

MH One key person is Magueye Ba, who is basically the builder, the master of the construction site. But what is particular about Magueye Ba is that he’s also a doctor. He’s educated and practices as a village doctor, but he’s quite an ingenious site coordinator; he has produced other buildings in the past, like Toshiko Mori’s cultural center in Sinthian, not far away from Tambacounda. The design we eventually worked out for the building uses a brise soleil brick wall for natural ventilation and cooling. I asked Magueye Ba to make a test façade of this, and suggested that he take a piece of the land on the hospital site to build it. I sent him some drawings and, after a while, he sent back some photographs. I noticed that they didn’t exactly show what I sent him in the drawings, and it certainly wasn’t on the hospital site. It was an actual building; Instead of just building a test façade, he had built a school for a nearby village that needed one. He took advantage of us needing a test façade and extended it into a small school. I thought this was brilliant, and beautiful. He took my logic and architectural interest and translated it into his own, and for the local needs. This new village school is co-designed and co-produced.

NA I imagine that the funds that were allocated to build the test façade came from the foundation that commissioned it. What was the client’s response when they heard that a new school building was built?

MH They loved it. And now, thinking back, I admit is was idiotic to say let’s build test façade. If we build a wall, let’s make something more out of it.

Village school built nearby Tambacounda.

NH How would you describe the role of the Foundation? Can you describe what they’re doing and how they select which projects to undertake?

MH We have to be very sensitive and aware of the pitfalls that this type of project can bring. The NGO culture that parachutes in and quickly leaves again can be extremely problematic. But without wanting to be too kind to my clients, what makes them different is that they are very locally invested, and have been for a very long time. They’ve been in Senegal for twenty years or so, and they focus only on two places: the region of Tambacounda and the capital. They don’t surf, or hop from place to place to place. This is one of the main characteristics that makes their work more substantial than other humanitarian architecture projects. The Foundation recently finished building another school in the rural village of Fass by Toshiko Mori. It took maybe two years to design and construct it, but to convince the head of the local mosque that girls can go to that school, and that not only the Koran is being taught there, took five years, and will take another one or two years really to implement. That is the actual work, even more than just designing the school.

NA Do you think the process of adoption differs in your case due to the program, as healthcare is often literally life or death?

MH Yes, but with any program, the social and the political comes into play and interacts with the architecture. For example, my project is for a maternity and pediatric hospital. For some reason in eastern Senegal, the majority of births are through cesarean sections, but we are trying to shift that. So the construction of the hospital is an opportunity to give cultural status to natural births. That is a much longer process that will go beyond the actual construction of the hospital, but we had to work with the doctors to create a shift in perception of birth techniques. This is a much larger and longer process than just building the hospital, but architecture is not just as a backdrop in that; it’s an active agent.

NH It’s clear that you’re aiming at a very inclusive understanding of a project that does not just end when construction is finished, but I’d be interested in also hearing more about problems, or even the contradictions that have arisen. Problems and contradictions are not necessarily negative; they can be very productive.

MH In this type of a project, one must inevitably deal with dilemmas surrounding economical disparity. The building will cost about a million-and-a-half euros. The salary that I pay my employees to work on this project is substantially higher than the salaries that are paid in Senegal. Is it unfair to spend money on salaries here in Switzerland? Should we be doing it in Senegal? We are trying to limit expenses in Europe, and are trying to keep as much money as possible in the region around Tambacounda. And of course, there is a bizarre equivalence of monetary value: one square painting of Josef Albers costs the same as our entire hospital in eastern Senegal. This is maybe perverse, but it also opens almost magic opportunities.

Manuel Herz Architects, Tambacounda Hospital, Tambacounda, 2018–2019, construction site, November 2019.

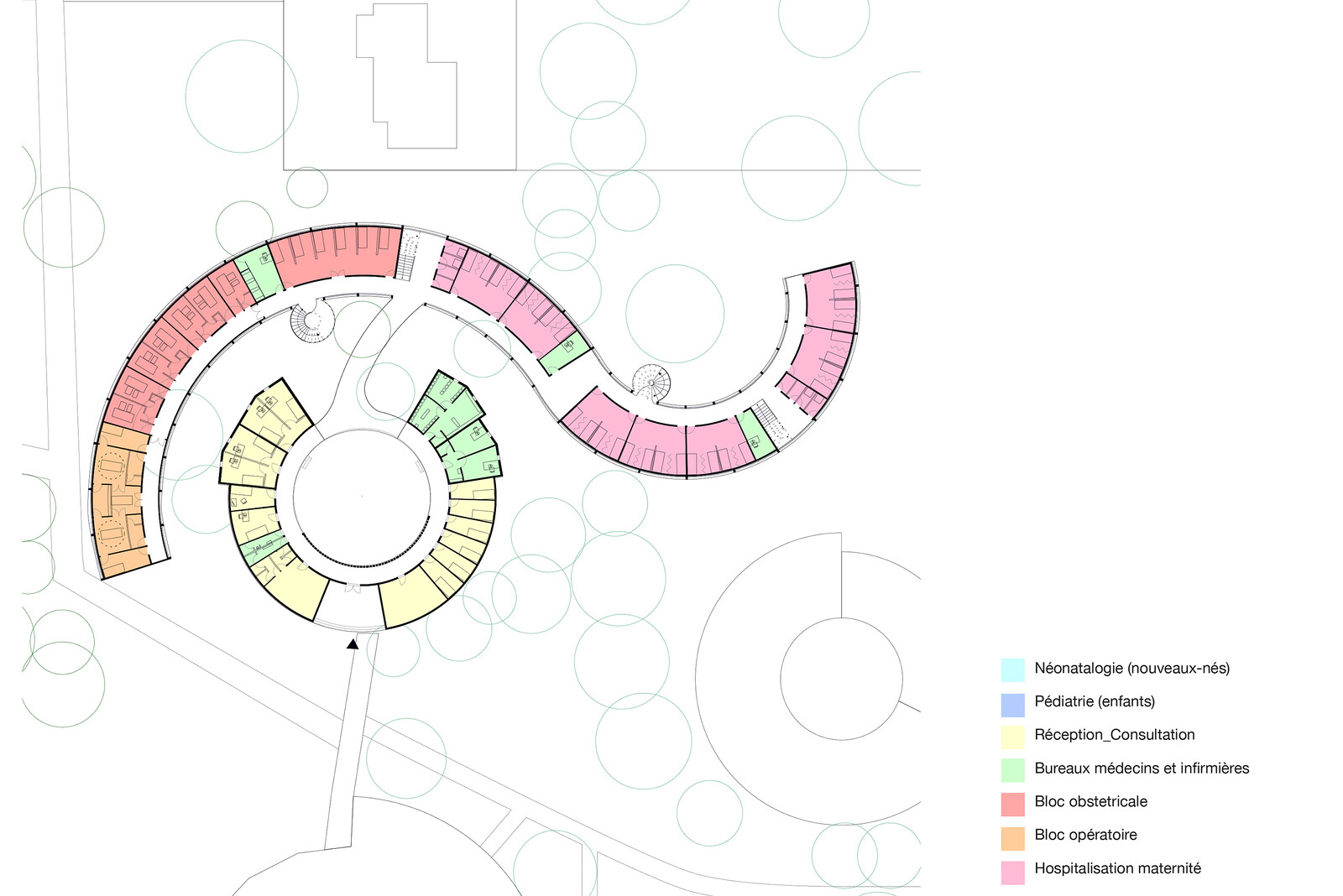

Manuel Herz Architects, Tambacounda Hospital, Tambacounda, 2018–2019, ground floor plan.

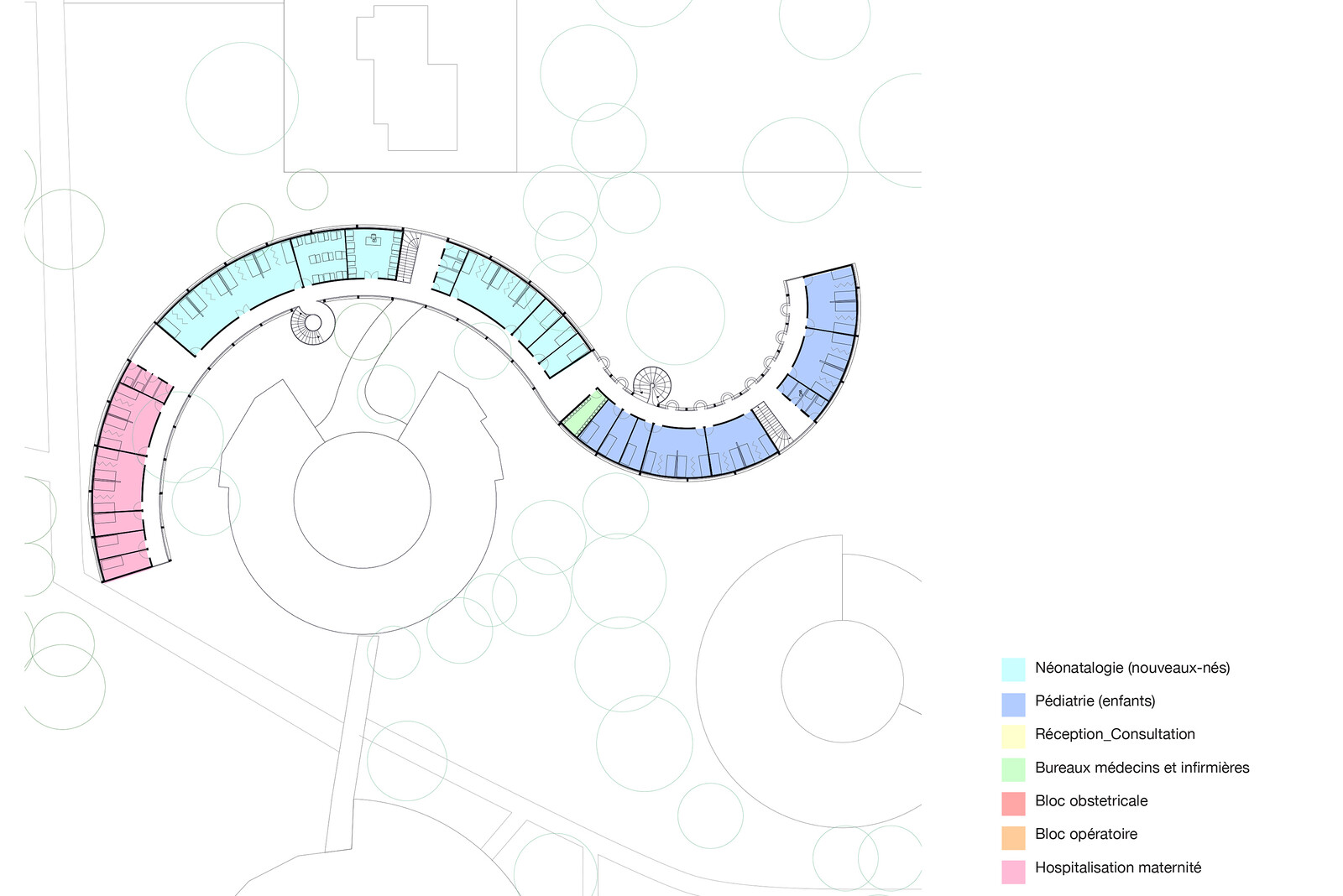

Manuel Herz Architects, Tambacounda Hospital, Tambacounda, 2018–2019, first floor plan.

Manuel Herz Architects, Tambacounda Hospital, Tambacounda, 2018–2019, climatic diagram.

Manuel Herz Architects, Tambacounda Hospital, Tambacounda, 2018–2019, construction site, November 2019.

NA What’s actually perverse about that?

MH That the price of a painting is equivalent to that of a hospital… Does this suggests that we should sell all the paintings and build a hundred hospitals?

NH That might be too easy.

MH Of course.

NH This is also where we can return to the question of humanitarian architecture. There are different ways to look at it. One is to be super critical with regards to the immediate economic mechanisms and inequalities, which might say that it’s not even worth intervening. Another way to see it is to say that it might be interesting to have experts and create productive misunderstandings, because it’s not obvious what the end, really of any project, will be. In his book Displacements, Andrew Herscher talks about some of the beginnings of humanitarian architecture. In the mid nineteenth century, in Victorian England, a lot of studies were being made of poor neighborhoods like Bethnal Green in London to improve them. The people who made these plans were very quickly labeled by the press as “humanity mongers,” judged for making a business out of poverty. But these people did not take it as an insult; they said, yes, it’s a business. We are experts and we’re good at it.

MH What fascinates me also about my own role there is that there’s not a golden path. As practitioners, our hands are always dirty. And I think that shows us something about architecture as a whole: that whenever architects do things, no matter how good it is, we will always mess other things up at the same time. So, you’re right: one could say let’s just let “them” work it out themselves. But that’s a very cynical, almost arrogant or disillusionist position. One can also go in with a hyper-NGO attitude that says we have the solution, let’s fix it. But there’s a middle ground. Maybe it sounds boring, but it is actually much wiser, which depends on a few key people who have a certain kind of sensitivity and know the limits of what to do. You cannot multiply it endlessly. The Foundation cannot build a hundred hospitals. They are dependent on two, three, four, five people who do it right. The kind of mix of individuals who have a certain sensitivity and awareness is important.

NA I think it also has to do with a wider attunement to the way change happens, or the way territories can be transformed. It’s very easy for NGOs, as you said, to come in with solutions, so perhaps a bit of humility is necessary. Managing expectations for these types of projects might be an essential ingredient.

MH When we came to a final design for the project, we had a meeting with the governor, the board of the hospitals, and every employee of the hospital to present the project. I thought the governor would come in with his entourage and would only let me speak for ten seconds before taking over. He listened to my presentation of the project for twenty-five minutes. He gave a very sharp response, and then he asked every person in the room, from the doctors and nurses to the director, the technician, and the handyman what they thought about the process, and about the design. He listened to them for two hours, and finally he said, Manuel, if you take into consideration all the comments that were made by all of these people, I hereby give you planning permission. That mix of democratic humility, in listening to everyone, and authoritarianism, of knowing that he has the power to give or take planning permission, is a very fascinating combination. Maybe it occupies this ground between cynicism and the NGO belief in “solutions.”

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

This conversation took place as part of the talks program of Design Miami/ Basel 2019.

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)