On a southwest corner in Hollywood stands the Fountain Vine Plaza, a two-storey strip mall with stucco walls and a blue-tiled roof built in 1984.1 It houses, among other things, a pharmacy, a hair salon, a pilates studio, a Japanese restaurant, a dentist, a Thai massage parlor, and the Los Angeles location of Studio20, the largest franchise network of studios dedicated to camming, or the adult webcam industry.2 Occupying a significant chunk of the top floor of the mall, Studio20 contains a series of individual rooms set off along a hallway. Each room is a set, with one half featuring a camera, lights, a computer, and other devices that facilitate the technical aspects of camming. On the other, furniture and decor are carefully arranged, typically to create the appearance of a bedroom. Just like the real thing, each “bedroom” appears a little different, as if personalized by its temporary inhabitant, while still adhering to a basic set of design protocols that produce the effect of a domestic space, rather than an office space in a strip mall.

There are rooms decorated for a surfer girl, a “girly” girl, and a girl who has kept her teddy bears.3 Meanwhile, although the online photo gallery for the Hollywood location comprises only low-resolution digital renders, the Studio20 website features a virtual tour of its facilities on Victoriei Square in Romania. It shows rooms dressed up in japonaiserie, lipstick wallpaper and framed inspirational posters, an ornate iron bed in front of a fake window looking out onto a country scene, wallpapers made to look like bookcases or faux white-washed brick, and a wall plastered with quotes by Albert Camus, Franz List, Antonin Artaud, and Karl Marx.4 The windows in each of the rooms are fake, and have been covered with adhesive film depicting cities such as New York, San Francisco, and Moscow—none of which house a Studio20 franchise. The images are cast in the same blues and oranges in every room, as if the studio resides in a perpetual twilight. There are vases of (assumedly artificial) flowers without water and antique-looking telephones that are unplugged. Some rooms have additions that would not commonly be found in someone’s bedroom, such as a dancing pole, whose relevance to the ostensible resident is supported by a framed poster with the phrase “Keep Love and Learn Pole” and a wall decal of a dancer. LED strip lights stretch along the ceiling line above the beds and reflective parabolic troffers fitted with fluorescent tubes are mounted elsewhere. In one room, an outlet box with exposed wires remains on a wall, assumedly out of the view of the webcam. Each room has the same red, diamond-patterned carpet and matching cove base, perhaps meant to make cleaning easier. And finally there are the beds, each of which are made simply with a fitted sheet and a few pillows.

Designed for the webcam eye, domesticity in these rooms is reduced to a bare set of signifiers without excessive concern for realism. The requisite appearance of the personal is rendered generic enough to be universally inhabitable. And yet, far from an afterthought, the decor of these spaces gives the work on display visual legitimacy, an aura of authenticity, while also contributing to the sexual capital of the worker within a field in which the domestic and the personal are associated with the erotic. These devices and decorations, properly assembled, constitute the architecture of a cam broadcast, both facilitating and defining the work on display. And, like one of the dolls nestled within a matryoshka, these seemingly mundane objects that remake an office into a set, convert a strip mall into a studio, and plug the body of a worker into a global economy composed of flows of data, capital, and cum.5 At each scale, architecture not only houses bodies but also choreographs them, connects them, and conditions them. That is, the body does not just inhabit architecture, but architecture inhabits the body.

.jpg,1600)

Typical cam room at Studio20.

Typical cam room at Studio20.

Detail of typical cam room at Studio20.

Typical cam room at Studio20.

The Structure

The load-bearing wall of this edifice is the webcam; without it, nothing else works. Cheap and ubiquitous, a webcam is a videotelephonic device comprising, at the minimum, a lens, a video sensor, and support electronics. When connected to a network, they produce a near-instantaneous feed, which creates a temporal relationship between the model and the viewers that distinguishes camming from other forms of pornography and helps to produce the sense of authenticity that is commonly cited as its primary draw.6 That is, watching a camming stream live is a fundamentally different experience than watching a recording of one.7 For one, you never really know what will happen next. There is no script, no editor, no filters—it feels real. And, while you don’t inhabit the same space as the cammer, you at least cohabit time.8

The earliest webcam was developed in 1991 at Cambridge University, where it broadcast an image of a coffee maker so that workers would be spared the letdown of finding it empty.9 But it did more than just allow researchers to peer through walls at a pot of coffee. By reducing wasted time and increasing caffeine intake, the webcam restructured the temporality of work and the biochemical composition of the worker. As webcams have proliferated and been incorporated into laptops and phones, their impact has grown exponentially, from facilitating remote work to enabling romantic partnerships across continents. Since they are vulnerable to hacking, they have perforated the sense of privacy offered by traditional architectonic elements like walls, which has been countered by a low-tech innovation: a strip of tape placed over the lens. A webcam does not just extend the visual acuity of the eye, but also redesigns the human itself and its relationships to other bodies, spaces, and objects.

In the context of camming, the webcam acts like a tether to the body, orienting and circumscribing potential movement as it divides a room into “on-screen” and “off-screen” zones. With the assistance of a picture-in-picture of their own feed, the performer discovers new ways to see themselves being seen. The webcam becomes a tool for self-knowledge in the service of self-improvement—a somatic hermeneutics of “playing to your angles” and “knowing your best light.” Then, once the feed goes live, the cammer experiences the transmutation of their own flesh and the room they occupy into a pay-per-act representation comprising 720 lines of 1,280 pixels that change color 60 times a second.10 Proliferating through digital networks, the pixelbody of the cammer and the pixelroom it inhabits meet the fleshy body of a consumer and are incorporated into it: a barrage of photons penetrate the consumer’s eye and are translated into neuronal signals that activate the paraventricular nucleus in the hypothalamus, releasing oxytocin into the bloodstream and producing a reaction in the spinal cord centers that, in turn, integrates the sensory pelvic neural inputs and drives a genital response.11

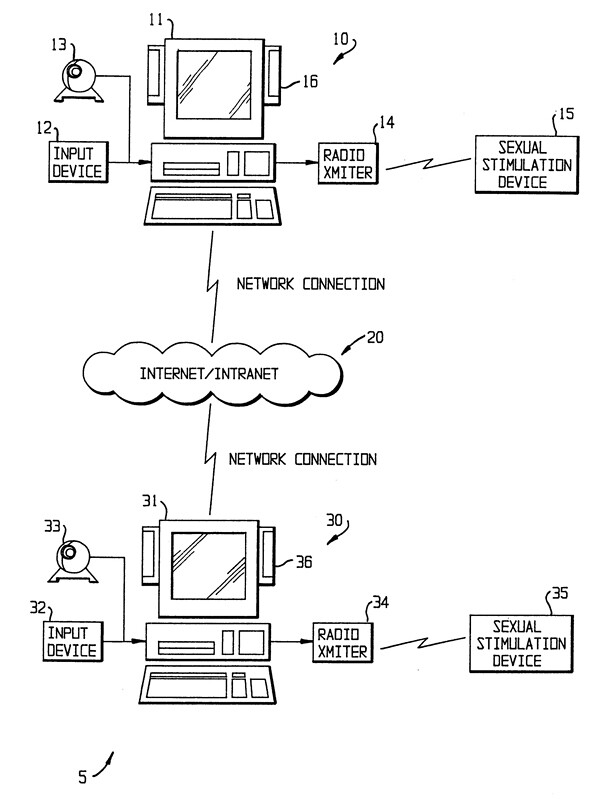

Warren J. Sandvick, Jim W. Hughes, and David Alan Atkinson, Method and device for interactive virtual control of sexual aids using digital computer networks, US Patent 6368268B1, filed August 17, 1998, diagram of the overall system for interactive use by two or more users in accordance with the preferred embodiment of the invention.

The Façade

Of course, the webcam doesn’t do this all alone. It’s a single joint in the megastructure of the camming industry, the ornamented façade of which exists online. The largest and most visible are the camming websites that most cammers use, such as Chaturbate, LiveJasmin, and BongaCams, to name just a few. They provide an audience for the cammers, alongside web designers, tech support, and pre-established relationships with financial institutions that facilitate payments—something difficult to do on one’s own due to frequent restrictions against sex work in the policies of major online payment services.12 In exchange for using the platform, the cammer typically must fork over a hefty cut of their profits, typically around 50% or more, although high-earners are often rewarded with a lower percentage.13 Cammers usually make their income through tips in the form of digital tokens, sometimes augmented by pay-per-minute private shows, which can also involve a two-way feed. Interfaces on these platforms are quite user-friendly, largely following general platform design protocols of Web 2.0, which could be understood as a sort of domestic architecture in its own right—the friendly, familiar façade of a suburban home rendered in HTML and CSS. You’re at home when you watch a camshow, both physically and virtually.14

In a way, camming is all about homes. Ensconced within the privacy of their own home, the consumer gets off on glimpsing into the home of the cammer, even if, in reality, that home is a studio set. At any moment, thousands of homes are coupled together into a larger machinic assemblage, a vast domestic urbanism—and that coupling is itself part of the eroticism. Beyond the scopic, cammers offer other forms of connection, creating supplemental sources of revenue through Amazon wish lists, where a fan can purchase gifts, both erotic and prosaic. Some cammers sell more intimate contact, such as personal items like used clothing. These other modes of payment bridge the virtual divide and involve senses beyond the visual, with a dildo or pair of dirty underwear serving as a sort of haptic prosthesis, rendering both the home and the body porous but still intact. Additionally, cammers often provide glimpses into their everyday life through cultivating online personas on social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter, and sometimes sell more direct and personal forms of contact like a Snapchat friendship.15 This additional labor helps magnify the effect of intimacy for the consumer, whose tastes—and spending habits—are often oriented towards the personality presented to them as much as their physical appearance.16 Even the precarity of the worker can be a selling point, with some consumers gaining satisfaction, or even getting off by providing financial support for student debt or helping the cammer make rent.

Through a live text-based chatroom, the consumer can participate in the experience, literally directing the way the cammer moves through their space and interacts with the objects within it.17 Many cammers publish menus that set prices for various sexual acts they are willing to perform in exchange for tips. Climax—somatic or theatric—can be hastened if the audience reaches an established monetary goal. Audiences often include trusted regulars, some of whom are chosen to act as moderators to protect the cammer from harassment.18 And increasingly, cammers use teledildonics, or sex toys such as dildos, vibrators, and fuck machines that can be controlled remotely through data links, haptically compressing geographic distance. Tipping serves as a trigger. Through this, the production of pleasure is outsourced, and the consumer gains technologically-mediated physical access into the cammer’s room and body.19

In a sense, cam sex is not so much a pornographic media as a unique form of sex in its own right. That is, while incorporating instances of sexual acts understood in the normative sense, such as jerking off, blow jobs, and fucking, cam sex itself is more than these acts alone. When you tip, your touch extends not only through the vibrating machine lodged in the anus of the cammer, but also through the webcam broadcasting the scene to an assembly of other unknown bodies whose pupils dilate, heartbeats quicken, and dopamine levels rise as they watch the body onscreen react. Camming is a technosocial orgy where bodies work to pleasure themselves and others by way of prosthetic technologies, supported by an infinitely complex set of monetary exchanges: from the exchange of labor for wages in tipping tokens by the consumer, to the cut handed over to the corporate platform for each token, and how that gets further divided up and distributed among a wide range of actors from employees to landlords to city governments.

And while it may not always be the central source of erotic excitement, at least some of the unique erotic appeal of cam sex comes from an awareness of your own participation in this complex architectonic assemblage. At any given moment, there are likely far fewer feeds featuring fornication than solitary or group masturbation, simply prone bodies on beds, or even, for sometimes long stretches of time, an empty room while the cammer attends to something off-screen. And yet, audiences will often stay put. Some may continue to masturbate, staring at the mattress, sheets, pillows, and wall paint that, awaiting the return of fleshy bodies, have somehow become erotic too.20 The turn-on of cam sex is not just the bodies of the cammers and the acts in which they engage, but also the relay of mics and speakers that let you speak with them, the economy that says you tip and they act, the spectral crowd of other masturbating bodies, and the way that the cammer’s room reflects their personality, just like yours.

The Interior

Of course, at Studio20, the rooms belong to nobody in particular, but rather a generalized and gendered identity realized through mass-produced furniture and decor. These decorations—and the labors of identity construction and signification they outsource—are part of the appeal of working in a studio, alongside equipment, utilities, tech support, training, makeup tutorials, promotion, financial support for clothing, a loan program, and importantly, distance from their actual home. That is, studios offer discretion for cammers who may live with family members or roommates who would disapprove of their work. Others fear that one of their followers might identify and publish their address, a practice known as doxxing, or worse. For example, a cammer known as Miss Dammer told a reporter from Vice about how one of her fans became obsessed with her, located her address, and identified her real name.21 He threatened to send screenshots of her feed to her parents. Things escalated to the point where he threatened to commit suicide if she ignored him. According to Miss Dammer, such intensity can be attributed to the affective and emotional labor implicit in camming, as well as the apparent intimacy produced by visual access to the cammer’s own bedroom, among other things. To escape him, Miss Dammer pretended to move to another state, and achieved this through decorating. She repainted the walls, replaced the carpets, and even brought in plants local to the region where she had ostensibly relocated. With a studio, in contrast, rooms are generic enough to make identification difficult while still providing that sense of authentic intimacy. And even if a fan does somehow find the address, the cammer should hopefully remain safe—just one of many working in a stripmall in Hollywood.

For cammers who can’t or won’t fork over thirty-five to fifty percent of their already-reduced earnings to rent a studio, or else live far from one, there are countless guides online to help navigate the labor of decorating, and which produce results largely similar to the rooms at Studio20. Cammers are encouraged to redecorate often to make their shows more interesting, to choose colors that complement their skin tone, to make sure they have a comfortable place to sit, and to position lamps for the most flattering lighting. The room is designed around the body, but the room also designs the body and its appearance. The guides instruct cammers to both “personalize” by choosing decor that matches their brand and “depersonalize” by removing things like photographs. One blog recommends wooden pallets because they “are ‘in’ this year,” and another says to look at Pinterest and fashion magazines for inspiration.22

Decorating for camming is not very different than decorating in general. It is referential, it involves a careful balance between the generic and the personal, and it is unpaid and under recognized while still producing value. That is, decorating is labor that enables a space to serve a particular function, be it camming or something else. It increases the value of a space as well as the capital—social or sexual—of its inhabitants. Finally, it works alongside a wide-range of institutions and apparatuses to help manufacture the subject it claims to represent. In other words, decorating is less a reflection of one’s personality than a means to produce it; a collection of citations, an assemblage of associations. Studio20 is something like a factory for the standardized mass-production of subjectivities rendered through interior design. Studio20 not only resembles domestic space, but functions like it.

Of course, the sets of Studio20 would not typically be construed as such. After all, legally-speaking, the building is zoned commercial. Nobody sleeps in the beds. Nobody calls the rooms home. These are spaces of work. But, then again, all this could be said of other spaces that would be construed as domestic. Across the housing-scarce city of Los Angeles, people skirt the law to live in industrial warehouses and commercial storefronts. Furthermore, studies indicate that as people increasingly use their laptops and phones in bed, the less they sleep in them, and the rising trend of people working from home suggests that the separation between workplace and living space that marked the last century was just a blip in an otherwise long history of their entanglement. Home, for many, is somewhere else than where they live, while for others, it is nowhere at all. The domestic, it turns out, is hard to pin down.

Rather than a fixed or universal descriptor, the domestic constitutes a historically contingent cluster of references informed by mediatic representations, social norms, and individual experiences. As a descriptor, it is at once fundamentally deictic and simultaneously embedded within an economy of shared associations and affects. For some people, the signifiers of the domestic produce the feeling of safety, but for many others they trigger trauma, often precisely because of the failure of a domestic space to conform to normative expectations and provide protective comfort. Likewise, sexuality and eroticism often belong to this economy, but often in the form of opposition, refusal, or violence. For instance, the image of the single-family, mid-century home as a locus of repression—where masturbation is shamefully concealed and adolescent lovers are hidden away in bedroom closets—reveals the sexual saturation of domesticity rather than negates it, while also introducing the possibility of transgression by establishing the rule.23 The vast quantity of domestic porn—from amateur to incest to maid—further evidences the ubiquity of this association. Sex, after all, tends to take place in homes. When it doesn’t, such as with public sex, it can extract eroticism specifically from its displacement. And, according to statistics provided by US government agencies, nearly six out of every ten sexual assaults occur within the victim’s home or the home of a friend, relative, or neighbor.24 In some cases, porn extracts erotic value from these acts as well.

Through decorating, the rooms of Studio20 take on the appearance of the domestic and appropriate its broad erotic value, while the studio and platforms work to convert it into money capital. Alongside this embedded eroticism, the domestic decor produces a sense of authenticity by making it seem like the cammer is working from home. It provides the effect of an amateur production, disguising the professionalism—the work character—of the studio. In this, decorating fosters the sense that camming is a labor of love rather than wage labor, which would suggest that the relationships forged between consumer and producer are somehow more than just transactional. Perhaps most importantly, by producing the effect of a bedroom, the cam feed appears as an unmediated glimpse at the worker’s “real” life and “real” personality, manifested in their chosen decor.

The sets of Studio20 are no less domestic than a home. They are not copies but the real thing—or as real as it gets. The domestic is a signifier without a referent that emerges out of an economy of circulating images, affects, language, capital, and bodies that includes camming as much as houses, books, movies, and memories. To represent the domestic is to produce it, to give it new meanings and new associations. There is no original home to resemble, eschew, parody, or appropriate, only a shifting constellation of resemblances and citations. Studio20 is a factory of domesticity, where decoration works in conjunction with the webcam, the computer, the network, and the platform to not only perforate other domestic enclosures, but also who they shelter. Bodies become entangled with one another and their environments to the point where they all begin to blur into a massive technosocial whole. The border marking where the body ends and architecture begins slips out of view.

According a building permit from May 15, 1984 from the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety archives, the architect was Lawrence Boyd and the engineer was Robert Shiang. It was developed by a company called Fine Developments and valuated at $1,482,980. Today Loopnet reports that a unit rents for $36 per square foot a year.

Studio20 also has locations in Hungary, Colombia, and Romania.

Karley Sciortino and Sarah Burke. “What It’s Actually Like to Be a Full-Time Cam Girl,” Broadly, February 28, 2018, ➝.

There’s also an image gallery with low resolution renderings of rooms rather than photographs.

“Cum” here refers metonymically to various bodily fluids produced through sexual arousal including, but not limited to, semen.

“They want that raw, vulnerable sexuality. They want to see something real,” states Nikki Night, who oversees performer training and development at Cam4. “Everything is so force-fed to us in this plastic way. That when you see someone actually have an orgasm for real and the look on their face—even your ugly cum faces—it’s that raw sexual vulnerability that is the juicy center of amateur and it’s even better when it’s someone that could, theoretically, live down the street from you.” Carrie Weisman, “Inside the Rapidly Growing Cam Industry That’s Changing the Porn Industry as We Know It,” Alternet, February 16, 2015.

In a 2008 revision to his 1999 book Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, Phillip Auslander updates his influential analysis of “liveness” in media to account for new digital technologies. Critiquing theories that valorize the “live” in opposition to the “mediated,” in particular by Peggy Phelan, he posits that “liveness” is a historically-contingent concept tethered to technological change, whose meaning is coconstituted with mediatized reproductions (xii). Auslander argues that early recorded media, such as film, attempted to emulate live performances, such as theater. In turn, the live performance simulates the mediatized performance, which becomes the measure of quality. “{Live} performance is now a recreation of itself at one remove, filtered through its own mediatized reproductions,” Auslander writes (35). Such an analysis can be applied loosely to the context of camming, where cammers mime behavior from professional porn and, in turn, professional porn attempts to achieve the “authentic” quality of nonprofessional media like camming. In fact, “amateur” is currently the 11th most popular porn genre on PornHub, and has been rising the ranks steadily for years. It’s also the genre of video with the longest viewing time. In fact, a “reality porn” industry has blossomed over the past few decades, which emulates the qualities of amateur porn but is professionally-produced. As Susanna Paasonen writes in Carnal Resonances: Affect and Online Pornography, “The transformations effected by Web distribution and digital production tools on pornography—its aesthetics, its economical underpinnings, and the experiences and resonances that it facilitates — cannot be understood apart from the shifting notions of amateur and professional” (71).

It is not just the cammer with whom you cohabit time, but also the rest of the audience—faceless and anonymous.

Cambridge University Department of Computer Science and Technology “The Trojan Room Coffee Machine,” ➝.

The actual resolution and frame rate of a webcam stream can vary significantly depending on the equipment and the connection.

This is just one possible chain of somatic reactions that constitute sexual arousal, and is far from universal. Arousal can involve the stimulation of many other parts of a body besides genitalia, or not involve genitalia at all. Additionally, some bodies are not aroused by stimuli such as camming, while other bodies do not experience sexual arousal in any form.

Meanwhile, banking institutions charge between 7% and 15% for payment facilities for camming sites in addition to a $1,000 annual fee, in contrast to the 2% to 3% typically charged for an online transaction. This is because they allege there are higher risks with the adult entertainment industry, although this has been contested and could very well be exploitation disguised with moralism. In fact, the economy of camming cannot be separated from the circulation of finance capital upon which it relies. Every camming transaction produces a profit for the banking industry, studios and platforms rely on loans or investment capital like any other company, and cammers often cite debt as a reason they got into it in the first place. Value fracked from a masturbating body—amounting up to $97 billion per year if you’re looking at the porn industry as a whole—circulates through the global financial system alongside mortgage securities and bitcoin futures. Capital is sticky. Rachel Stuart, “Webcamming: The Sex Work Revolution That No One Is Willing to Talk about,” September 04, 2018, ➝.

“Camming Sites Hiring Webcam Models (Guide To Get Started),” Webcam Startup, ➝.

Lurking behind this friendly façade, the organizational structure of cam sites reproduces social stratification according to gender identity and race. For example, it categorizes bodies as “male,” “female,” and “trans,” effectively excluding bodies that do not conform to normative expressions of these or other identities. Meanwhile, as Angela Jones has illustrated, sorting systems on the platforms frequently place black bodies lower down on the site, with a user sometimes having to scroll for several pages before encountering a non-white body. This reinforces racialized wage disparity and buttresses the sexual capital of white cammers, which, in turn, has material effects on lived experience. Angela Jones, “For Black Models Scroll Down: Webcam Modeling and the Racialization of Erotic Labor.” Sexuality and Culture 19 (2015): 776–799.

The top destination sites from Chaturbate, for example, are Instagram and Twitter. “2018 Year in Review,” Pornhub, January 31, 2019, ➝.

Sciortino and Burke, ➝.

Far from insignificant, the chatroom constitutes a fundamental aspect of the camming experience, facilitating exchange among the consumers and with the producer. Some cammers are able to gather together an audience of repeat customers, a familial circle of virtual friends who, in certain cases, text each other and even meet up IRL. Allison Tierney, “Meet the Bouncers of Camgirl Chatrooms,” Vice, May 12, 2016, ➝.

Ibid.

Teledildonic gadgets are vulnerable to hacking, and there have been reports of teledildonic companies covertly recording a user. Therefore, the architecture of camming grows even larger and its borders murkier. The subject, prosthetically tethered to this massive and dispersed architecture, gives up a degree of control over their body.

In other words, the pleasure produced by your connection to the body of the performer is in part due to the material fact of the connection itself. This is not a seamless mass but rather the seams—distances bridged not collapsed—are themselves erotically-charged. As an experience of proximity is produced virtually, the physical distance between the body of the pornified other and your own simultaneously comes into focus in a way absent in other porn. Your technologically-enabled capacity to touch the bodies of others virtually also acts to expose your incapacity to do the same physically. In this way, camming affirms the placedness of the various actors involved at the same time as it seems to negate it.

Annie Lord, “The Emotional Side of Camming,” Vice, September 27, 2018, ➝.

“The transgression does not deny the taboo but transcends it and completes it,” writes Georges Bataille in Eroticism (63).

“National Statistics on Sexual Violence,” Connecticut Alliance to End Sexual Violence. ➝.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)