“Queerness is not here yet. Queerness is an ideality,” writes José Esteban Muñoz in his introduction to Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Utopia.1 Published in 2009, Muñoz argues against the pragmatics of the present and sees radicalism in the potential of an evasive event horizon. As such, he values utopia as a map towards the potentiality of queerness—a future world just beyond reach.

This position, by default, destabilizes notions of queer space in relationship to architecture that were historically tied to acts of desire, transgression, and artifice.2 Texts such as Stud, edited by architect Joel Sanders (1996) and Aaron Betsky’s Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire (1997) focused primarily on spaces occupied or designed by gay men and were temporally concerned with observing and theorizing contemporaneous conditions—bars, bathhouses, nightclubs—conditions that Betsky has more recently noted have been largely assimilated out of existence.3

The reemergence of queerness among a younger generation of practitioners is similarly concerned with the present, specifically the homogenizing effects of architecture culture and aesthetics, which Adam Nathan Furman writes are so dominated by hetero, cis-male identity that plurality is bluntly and effectively silenced.

When a project or series of projects that operate as a product of queerness is built proudly in the shared sphere of the city, whenever an architecture deviates from the shockingly narrow, heteronormative framework of mainstream architectural culture’s arbitrary parameters of taste, they are instantly othered as unserious, capricious, ridiculous or, at best, exotic—all of which are the kiss of critical death.4

The sun seems to have set over one conception of user-oriented queer space, however, and now rises over queer aesthetics, an arena that with the opening of projects like the Cruising Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and PIN-UP magazine proves the coalescing of a moment, if not movement.5 Yet we should not forget that Muñoz is aiming for the moon. His insistence that we haven’t gotten there yet is helpful when trying to comprehend the bundle of glass and gleaming white stucco at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and North Mccadden Place, otherwise known as the Los Angeles LGBT Center’s Anita May Rosenstein Campus by New York-based architects Leong Leong and LA firm Killefer Flammang Architects (KFA) that opened in this past April. Over 180,000 square feet, with some four acres dedicated to the support of LA’s LGBTQ community, it’s an ambitious project that trades more in vocabularies of contemporary, academic form-making than queer aesthetics. Although uneven in its execution, the campus necessitates a discussion of queer space, even as the architectural expression dodges such categorization.

Additionally, my own authorial identity as a straight, white, cis-woman make any wholesale claims on “queerness” a bit dubious. But, it is in the spirit of Muñoz’s queer futurity and the belief in the temporal gesture that uproots our assumptions of the “here and now,” thus catapulting us ever-forward, that I assert the Anita May Rosenstein Campus to be not a piece of queer architecture, but toward it. The campus provides some insights about changing parameters of queer space and what might be grounds for queer architecture in the future.

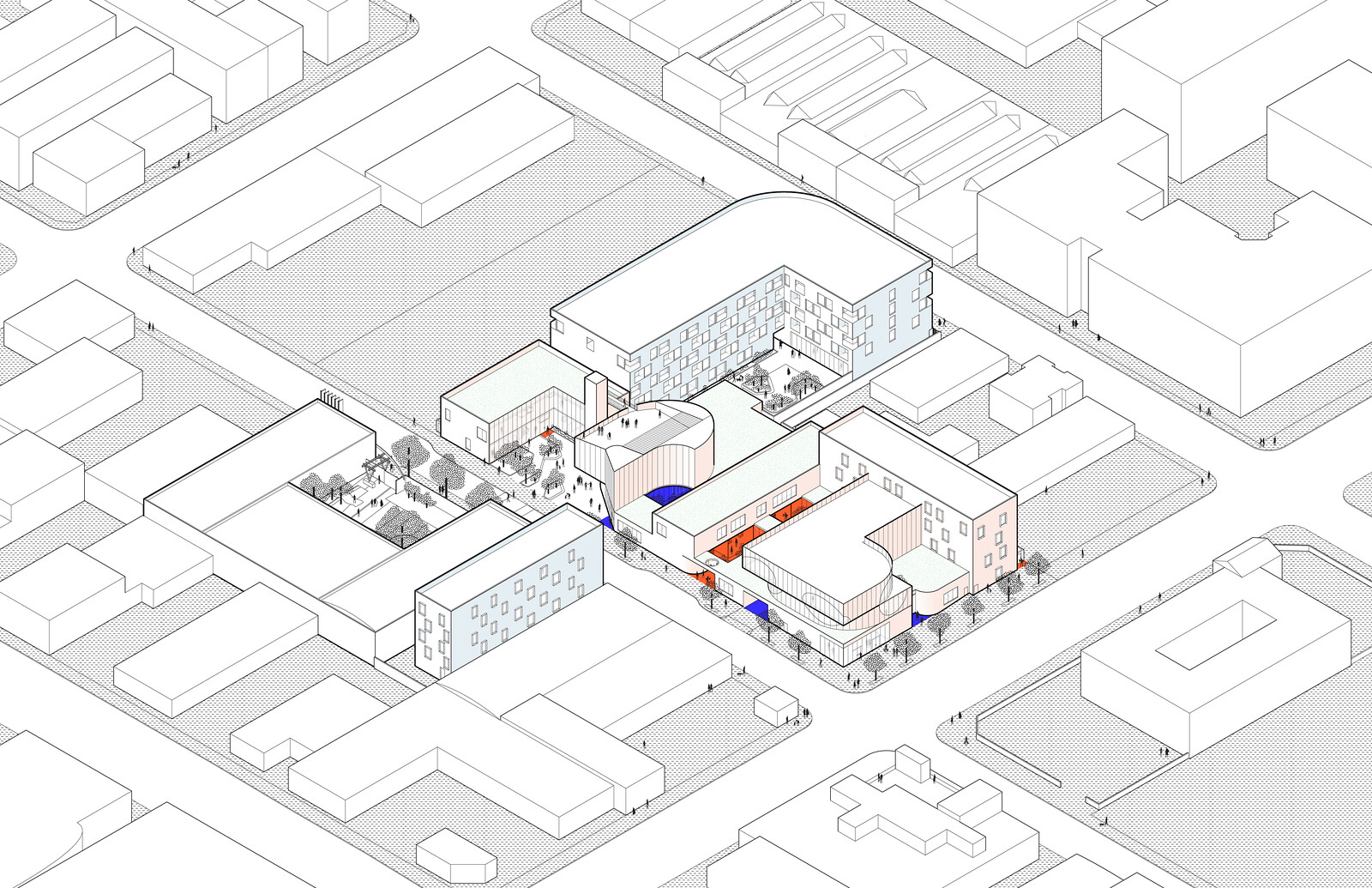

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019, axonometric.

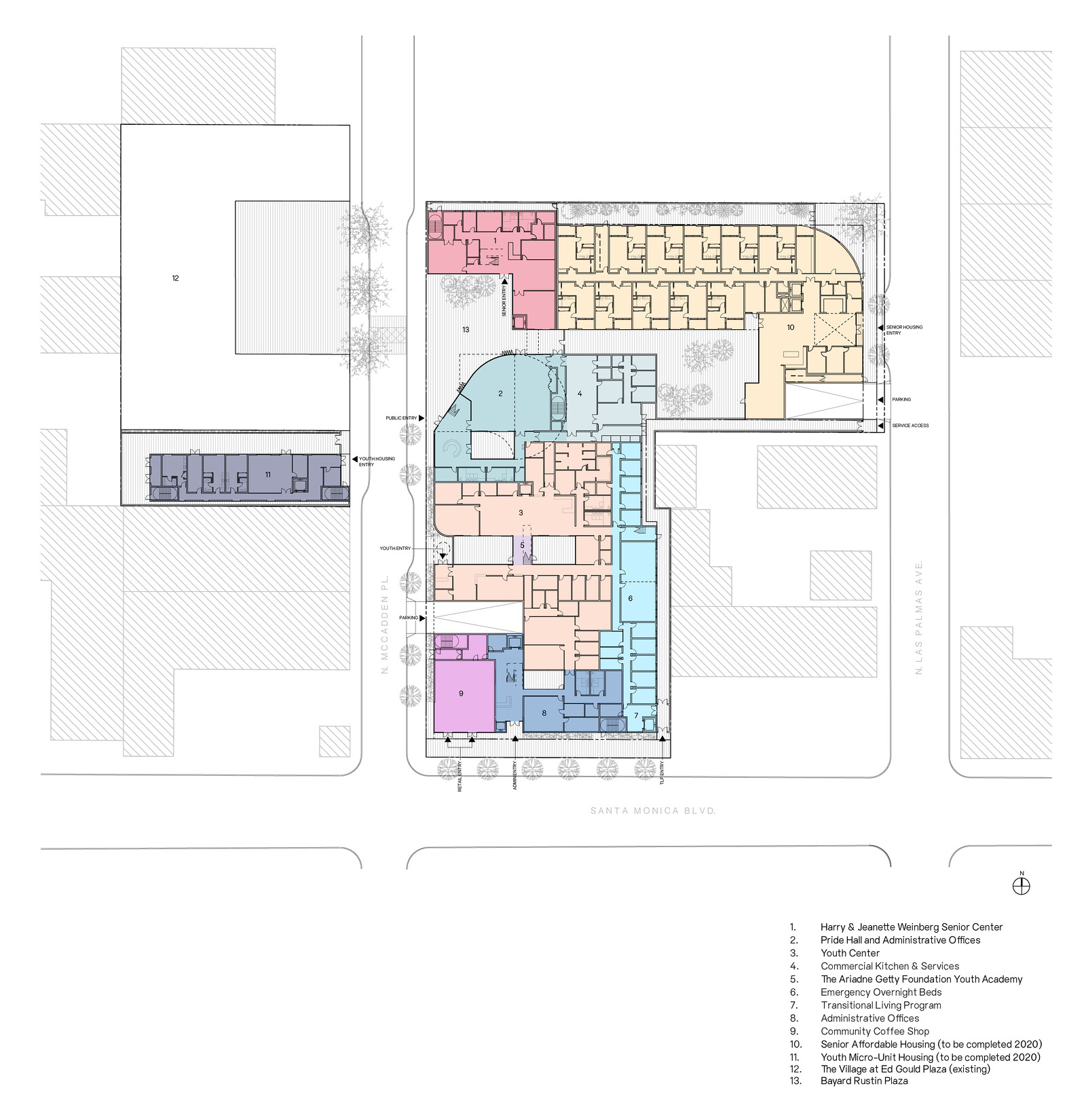

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019, ground-floor plan.

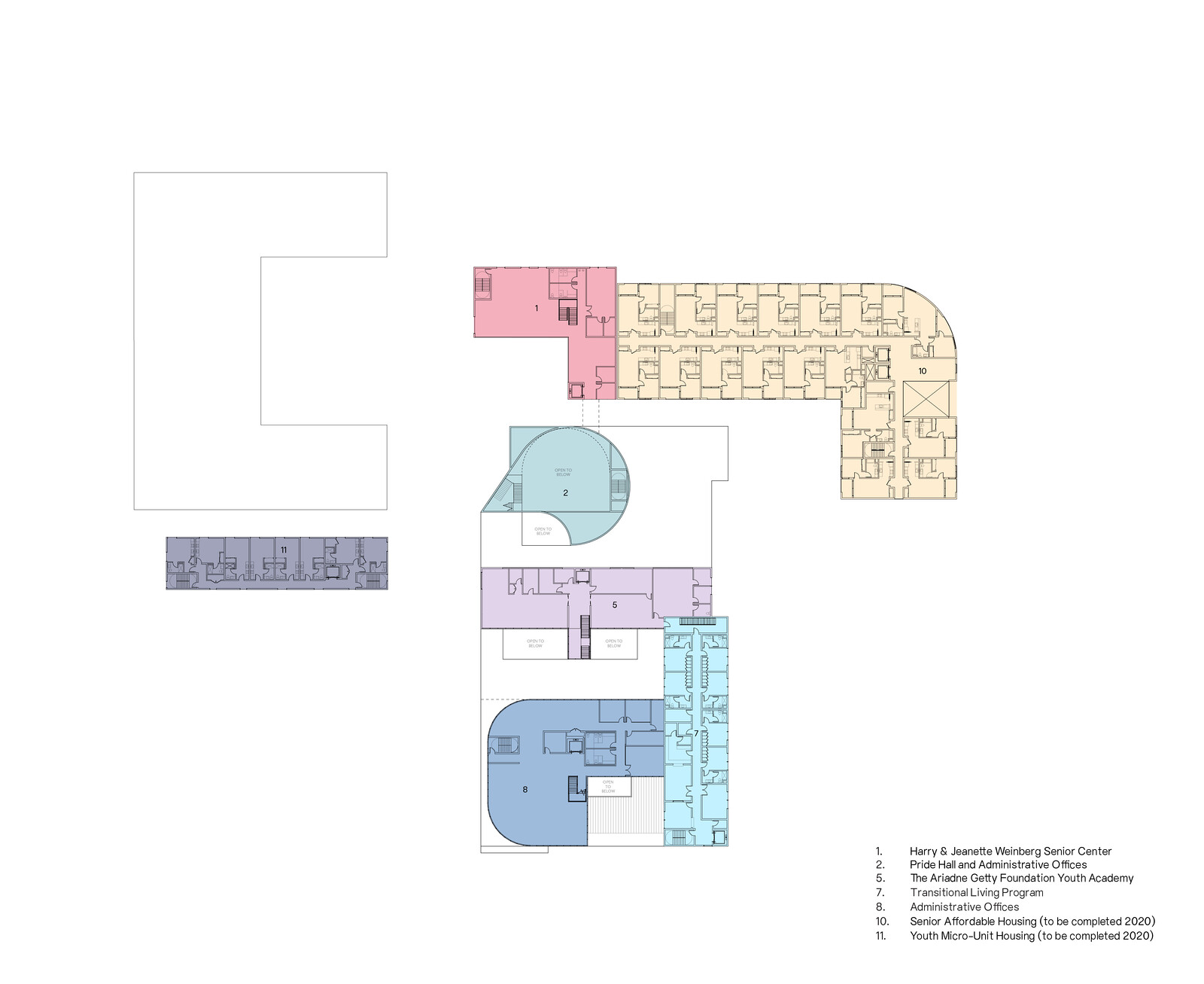

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019, second-floor plan.

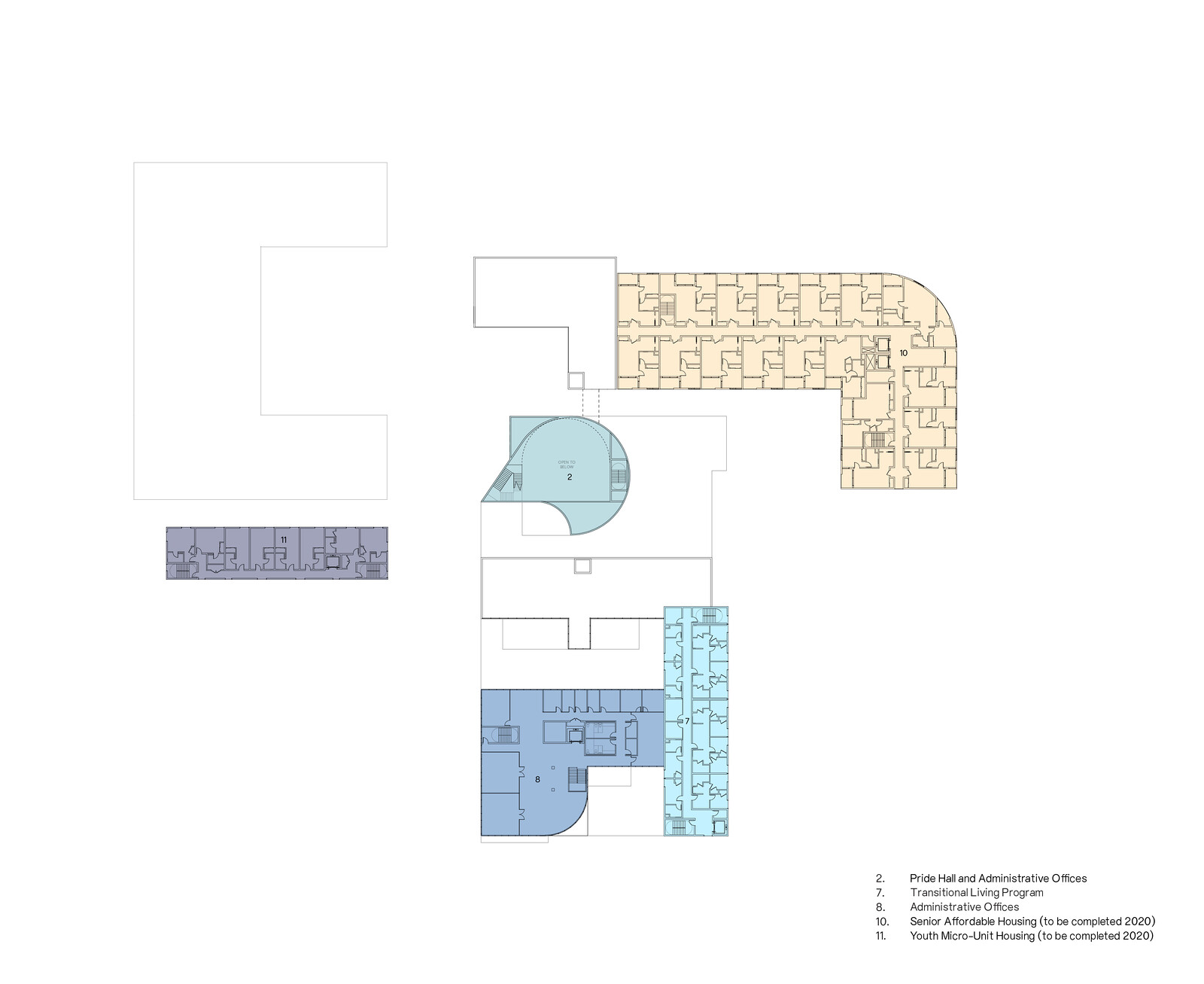

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019, third-floor plan.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019, axonometric.

Founded in 1969, the Los Angeles LGBT Center is a nonprofit organization that offers health and social services, public programming, housing, and advocacy within the city. In 2014, in partnership with housing developer Thomas Safran & Associates, the Center issued request for proposals for a new campus to be built across the street from one of its existing outposts, The Village, at Ed Gould Plaza in Hollywood. The RFP outlined a city block packed with programs: affordable housing for seniors and supportive housing for young adults, 100 beds for homeless youth, a new senior center, retail space, a youth center, event spaces, and an administrative headquarters.

Chris and Dominic Leong, with KFA, entered and won the competition for what would become the Anita May Rosenstein Campus, beating out a shortlist of LA-based architects that included Michael Maltzan, Frederick Fisher, Predock Frane, and MAD. Their design placed senior and youth housing at opposite ends of the site, with outdoor spaces and services forming a connective tissue between the residential bookends. The showy administrative building on the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and McCadden Place is meant to be the most public face of the project.

According to the LGBT Center, the organization serves more than 42,000 clients each month. Mixed use and intergenerational, the campus caters to the variety needs of Los Angeles’s LGBT community with unprecedented scope. “The term ‘utopian’ was in the actual brief,” recalls Chris Leong. And it is utopian, echoing Muñoz’s event horizon by coincidence, with regards to the scale and ambition of the project, and also it’s embedded hope. The Anita May Rosenstein Campus is assertive, demanding in square footage that a historically marginalized community has the right to command civic space. But what is the shape of that civic voice?

“We designed it from the inside out,” says Dominic Leong. “Now, five years later, we are thinking about how historically queer space and sanctuary spaces have been mostly interiors, like clubs. So what does it mean to move from the space of interiority to the city?”

The whole of the LGBT Center’s Hollywood facilities straddle North McCadden Place, with the Anita May Rosenstein campus sitting across the street from The Village, which was built in 1998. Protected by a large gate and tall, mature plantings, The Village shields itself from the urban context. This is a hangover from when this was a pretty sketchy neighborhood, but also an important tactic in defining safe space. This part of Santa Monica Boulevard has changed in recent years, with art galleries like Regen Projects (designed by Michael Maltzan Architects) and LAXART (by Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects) taking root. The corner strip mall now boasts a hot pink doughnut shop owned by actor Danny Trejo.

There’s been a cultural shift, too: a desire to be recognized. The LGBT Center wanted an iconic building with outdoor spaces open to the public. It’s a desire that in 2013 might have signified the cumulative triumphs of the last 50 years of gay rights movement, but in 2019, under the bile spewed by the Trump administration and continued violence against trans individuals, highlights the political significance of edifice.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019. Photo: Iwan Baan.

Leong Leong and Killefer Flammang Architects, Los Angeles LGBT Center Anita May Rosenstein Campus, 2019. Photo: Iwan Baan.

At the heart of the architects’ design is Bayard Rustin Plaza, a new open outdoor area flanked by the new senior center and Pride Hall, a rounded, fifty-foot-tall event space with a phalanx of bi-fold glass doors. It sits directly opposite The Village’s courtyard and is meant to extend that original space across the street. Straightforward with tasteful paving, planters that double as seating, and a few trees, the plaza is nice, slightly corporate, and rendered light gray and white. But it’s significance lies in what missing: there’s no gate. On opening day, a block party closed North McCadden Place, creating a kind of temporary micro-utopia as people of many ages, sexualities, races, and genders listened to Mayor Eric Garcetti speak and Trans Chorus of LA sing.

Still, at the opening, a handful of bigots with hateful picket signs clumped at the police barricade along Santa Monica Boulevard. An officer asked one man, “Don’t you have anything better to do?” The celebratory crowd, of course, exponentially outnumbered demonstrators, and the new administrative wing, rising just three stories above the sidewalk, dwarfed the meager protest.

The administration building broadcasts the Center’s identity with a certain degree of defiance, if not defensiveness. It is a layer cake of glass and stucco, a rectangular first floor hugging the corner with a retail storefront (soon to be a café) and topped by a double stack of somewhat U-shaped volumes, each with opposing filleted corners. It’s an odd piece of architecture—a difficult figure that flickers in and out of convention, depending on perspective and speed. Sometimes the cantilever of the top U juts out like a prow or an upturned chin. And other times the building appears highly normative; a glint of mid-rise curtain wall against more familiar repetitions of housing (like the campus’s transitional youth residences and the swell of other new multifamily housing along the boulevard).

Dominic Leong draws parallels between these multiple readings of the administration building and the many communities the LGBT Center represents. “Queerness is about fluidity and a continual becoming, not a fixed definition,” he says, careful to note his own ally status in regards to the community and the privilege that comes with using its terminology.

Jack Halberstam, in his essay “Unbuilding Gender,” uses Matta Clark’s cutting and carving into abandoned structures to discuss ways of dismantling assumed binaries and constructing trans legacies.6 At certain angles, large circles appear to be cut into the administration building’s glass façades, a la Gordon Matta Clark. Surface geometries—patterned versus non-patterned glass panels—span between the floors of the administrative wing. While early models and renderings suggest deeper voids and more pronounced fragmentation, the reality of the circle effects prove more optical illusion than “anarchitecture.” Their legibility is often compromised by reflection, but when the light does behave, the effect of the circles aligning and dividing is thrilling.

[Trans bodies] function not simply to provide an image of the non-normative against which normative bodies can be discerned, but rather as bodies that are fragmentary and internally contradictory; bodies that remap gender and its relations to race, place, class, and sexuality; bodies that are in pain; bodies that sound different from how they look; bodies that represent palimpsestic identities or a play of surfaces; bodies that must be split open and reorganized, opened up to chance and random signification.7

Halberstam’s essay was published in 2018, years after the Leong Leong/KFA design broke ground, so there isn’t any direct influence of the former on the latter. However, they can be understood in parallel—body to building, identity to icon. The architects’ use of multiplicity as formal gesture anticipates, but doesn’t quite achieve the dynamics of Halberstam’s description. We’re not there yet. But in this pairing there’s an opportunity to speculate on future vocabularies of trans or nonbinary architecture: fragmented, contradictory, multifaceted, remapped…

Splitting open the Anita May Rosenstein block reveals a nuanced set of interconnected spaces that comprise and connect the interior, which hosts a suite of youth services. If the exterior of the campus, especially the administration building, the event hall, and outdoor plazas, is about broadcasting a queer civic presence with heightened confidence, inside is about responding to the difficult and violent realities of being a gay or trans person living on the streets. Programs include a youth center, The Ariadne Getty Foundation Youth Academy, emergency beds for homeless young adults, a communal kitchen, and facilities for the transitional living program, which provides housing to LGBT youth and the support to help them get a job and enroll in school.

Two opposing conditions define the interior: sanctuary and visibility. Youth clients need to have privacy and feel safe, while Center staff must be able to see what is going on in order to supervise. A twin set of glazed interior courtyards organize the campus plan, separated by a stair leading upstairs to the academy facilities. “It was critical to provide safe outdoor space,” says Dominic Leong. “If you live on the street, you don’t have that.”

Narrow and tall, the courtyards are terrarium-like: intimate and sparsely planted. They offer small slices of sky, but plenty of daylight into the heart of the building. The architects worked with Wollcott Architects on the interior finishes, which adopted a rather contrary sensibility to the rigorously monochrome exterior. Shades of cobalt and teal color the walls and floor, with an occasional acid green upholstered bench. The blues reflect off the glass, frustrating transparency with prismatic washes of color. And a little bit too “on brand,” rainbow-flecked terrazzo is used throughout the campus.

Leong Leong claim that they were inspired by Hollywood’s apartment court housing—cottage units clustered around a strip of overgrown green. There’s something appealing about the appropriation of a prevalent residential typology for use in an institutional space. The common areas, although not homey, are modest and bright, welcoming. But it is not especially notable because of this queer trope of domestic detournemont. Instead, there’s an interesting inversion: a semi-public exterior space is sampled from the urban fabric and brought inside. Once there, the courtyard successfully acts as the center of disparate programs.

The actual housing on site, the shelter and the dormitory, are serviceable and most necessary, yet drably conventional. If there was any spot on the campus that needs a boost of utopia, a vision for how architecture projects into the future, it’s these rooms, which are reached by back stairwells and double hung corridors. Teal blue paint and polished concrete floors isn’t enough. Munoz, referencing Roland Barthes, notes that utopia is the quotidian, everyday, writing: “[T]he utopian can be glimpsed in utopian bonds, affiliations, designs, and gestures that exist within the present moment.”8

Some of the campus’s residential structures, also designed by Leong Leong and KFA, are still under construction and slated for opening in 2020, such as youth micro-unit housing next door to The Village and affordable senior housing that connects to the senior center at the northern part of the site. Floor plans draw the senior housing as six floors of one-bedroom units; simple spaces with large windows and small balconies.

Halberstam, in discussing queer temporality, points out that the AIDS epidemic erased the possibility of a future for the gay community. Imaginings of growing old were cut short. How could one even dream of affordable senior housing in the face of disease and death? “[Q]ueer time, even as it emerges from the AIDS crisis, is not only about compression and annihilation; it is also about the potentiality of a life unscripted by the conventions of family, inheritance, and child rearing,” writes Halberstam.9 So while there’s nothing particularly radical in the design of the housing, its potential importance lies in the fact that it exists at all that it concretizes aging as an event horizon for the LGBT community. And maybe that’s enough for now—that a particular utopia is possible and there’s an opportunity to get there.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Utopia (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009), 1.

Aaron Betsky, Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1997), 5.

Jaffer Kolb in conversation with Betsky, “Working Queer,” Log 41, Fall 2017.

Adam Nathan Furman, “Outrage: the prejudice against queer aesthetics,” Architectural Review (March 2019).

➝.

Jack Halberstam, “Unbuilding Gender,” Places Journal, October 2018, ➝.

Ibid.

Muñoz, 22.

Judith Halberstam, “Queer Temporality and Postmodern Geographies,” In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 2.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)