Jencks was right when he predicted that “the iconic building is here to stay.”1 Its generalization and expansion in the form of so-called “image architecture” has become central to the way cities are being shaped across the world. Since the early 2010s, the phenomenon of image architecture has been joined by another one essentially based around similar tenets, if often adjusted to a rhetoric of economic modesty and smaller scales: a version of postmodernism currently present in biennales, architecture schools, and practice, in Europe and the US alike.2 Emphasizing graphics, style recycling, and questions of “shape”—whilst mostly void of the deeper social and cultural agenda underpinning the original postmodernism—this twenty-first century instantiation reinforces what we can understand as a representational break grounded in a duality between building-as-representation versus building-as-spatial-organization, one where the domains delineated by each term are a priori independent. This divide lies also at the core of image architecture, which for this reason alone can be regarded as a fundamentally postmodernist trend. Indeed, it is no coincidence that Jencks, the champion of postmodernism par excellence, addressed image architecture with such interest around the mid 2000s.3

Despite its widespread use in architectural discourse, the term “representation” is not often sufficiently understood to operate simultaneously on two different semantic regimes. The first alludes to a graphic or physical depiction (a floor plan, a model, etc.) that stands for an outside referent (a work of architecture) on which it is dependent, and therefore subordinate to. The second arises when a work of architecture, formerly a primary referent, becomes that which stands for another, whether internal or external to the work itself. In this case, the work represents values pertaining to a particular realm (e.g. political, social, vernacular, ethical, religious, etc.), and by embodying these values it acquires a certain meaning. Symbolism, ornament, adornment, and related notions around the question of signification typically fall into this register.

Though rather old in its embodiment in built form, the duality of building-as-representation and building-as-spatial-organization had a defining moment in Learning from Las Vegas. In the introductory paragraphs of “Ugly and Ordinary Architecture, or the Decorated Shed,” Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour (VSBI) refer to the “duck” and the “decorated shed” as “manifestations” of the same attribute, namely, the lack of consistency, the “contradictions” that may be exploited between, on the one hand, “form, structure and program,” and “symbolic and representational elements,” on the other.4 While typically construed as different, this suggests that the notions of the “duck” and the “decorated shed” share, in fact, the same ethos.

This realization, however, can only be productive if such an ethos is grasped more precisely. In this regard, it is necessary to analyze the relations between those sets of aspects whose contradictions VSBI wish to exploit. When constructing the definition of duck and decorated shed, they added 3) “shape” or “overall symbolic form”—which has been more recently captured by the term “envelope”—to 1) “system of space, structure, and program” and 2) “representational elements.” In the decorated shed, the representational elements are applied independently of the other two; signs are deployed on a plane that is either physically or compositionally detached from a generic, representationally mute “shape.” The duck, conversely, features an envelope whose very three-dimensional profile constitutes the representational element itself, resulting in what the authors called “building-becoming-sculpture.” In the decorated shed, a rapport between the nature of the “system of space, structure, and program” and the representational character of the building is inexistent.5 Yet similarly, the definition of the “system” in the duck remains basically unaffected by the nature of the representational element: it gets merely “distorted.”6

Implications follow on two levels. Firstly, a description of the internal spatial arrangement that might be made to correspond to the model of either the duck or the decorated shed is never provided. What would a section or an axonometric drawing of the inside of the “duck” look like? One is left to believe that this matter is irrelevant to the authors. Instead, their theory emphasizes image, and therefore the conditions of interiority could be any.7 Secondly, a careful study of the array of instances given in Learning from Las Vegas reveals that such a distortion of the system of space alludes, in fact, solely to the exterior, that is, to the effect of a “duck-like” profile (as opposed to a “box-like” one) on the three-dimensional contour area of the building, whether the profile be exemplified by that of a cross-shaped Gothic cathedral or a hamburger stand in Dallas.8 In other words, the internal spatial arrangement of a “duck” and a “decorated shed” may very well be identical; for example, one based on a floor-upon-floor sequence or a single empty space. Which is to say, the “duck” is fundamentally but a “shed” in the overall shape (i.e. volumetric outline) of a particular animal species.

Epistemologically, what this analysis shows is that both the concept of the duck and that of the decorated shed rest on the basis of the representational break. Accordingly, whether a building is characterized as a duck or a shed, it will embody the duality of building-as-representation versus building-as-spatial-organization, and will therefore revert back to the same old tradition. That said, while essentially keeping with this tradition, Learning from Las Vegas prompted an exploitation of the duality to such new levels of intensity and variety that it originated a shift of exceptional proportions. As opposed to any number of historical cases—such as, say, Neoclassical architecture—where a building’s representational dimension specifically referenced a codified stylistic format (the conventions of classical language)—VSBI extended a building’s representational content to virtually any imageable vocabulary: that of a Renaissance temple, the profile of a sausage, commercial signage, etc. In so doing, they intensified the reach of the duality’s first term, building-as-representation. However, in proposing a deliberate manipulation of the disagreements between the two terms, they further fueled the schism between them. As a result, the representational possibilities enabled by VSBI’s extreme exploitation of the duality are indeed exponentially greater, but so is the gap with respect to spatial organization.

Consequences of the “Bilbao Effect”

In the years following Learning from Las Vegas, the original postmodernism—in the representational sense relevant here—went by and large off its initial purpose, thereby anticipating in some respects the re-enactment presently being witnessed. Its initial commitment to the integration of buildings into the urban realm by way of engaging a wider public (in contrast to distant, self-alienating modern language) ended up evolving into largely insubstantial, glib decoration. A considerable part of the production of the 1970s and into the 1980s found itself trapped in what was labeled as Historicist Postmodernism, a stylistic fad that embraced the use of conventions pertaining to earlier time periods. Triggered by the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, it was only a quarter of a century after VSBI laid the discursive foundations for a particularly acute exploitation of the representational break that it started to be fully implemented. With the completion of Gehry’s building, the question of imageability (understood here as the region of possibility within which a work of architecture may powerfully resonate with the subject’s faculty to form and interpret mental images) as well as related issues of meaning acquired renewed weight—weight whose effects are still wholly being experienced today.9

The importance of what Gehry’s building brought about for the city of Bilbao is well known.10 To be sure, Jørn Utzon’s Opera House had similarly put Sydney on the map twenty-five years earlier, while Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s AT&T building in New York may have gotten comparable attention in the press. Yet it was Gehry’s titanium construction that brought on an explosion of image architecture. In the context of globalization’s tendency towards borderlessness, the fixity of codified architectural styles has been replaced by code-free icons, capable of being at once representationally potent while flexible enough to host a diverse array of semantic associations. The main purpose of image architecture’s most ambitious cases is defined by a strong demand for instant fame and economic prosperity, which are entrusted to the attention-grabbing qualities of imageability. Two examples that followed on the successes of Gehry’s Guggenheim, both completed in 2003, can be cited as cases in point: the Kunsthaus in Graz by Peter Cook and Colin Fournier, and the Selfridges Department Store by Future Systems.

The Return of Debates on Representation in the Twenty-First Century

Following the Bilbao Effect, a diversification of architectural strategies resonating at the level of imageability occurred that expanded to a broader range of scales and programs than that of Gehry’s building, reaching an unprecedented peak during the first decade of the twenty-first century. Given this outburst, a significant section of international architectural discourse shaped up accordingly, culminating around the mid 2000s with a number of writings by Jencks and Alejandro Zaera-Polo as well as the eleventh issue of Hunch, titled “Rethinking Representation.”

A close reading of this 2007 issue of Hunch reveals the same dynamic playing out everywhere today: namely, that despite their growing elaborateness, the representational concept-operations driving image architecture tend to target issues of envelope, surface, outline, and graphics while leaving spatial organizations fundamentally unquestioned. Editor Penelope Dean structured the issue around ten terms that she called “representational labels,” each distilled from a piece by a different contributor.11 For example, under the “Apply” label, John McMorrough wrote about how the application of bi-dimensional painting may be utilized as a means to alter the perception of three-dimensional space. To illustrate this, McMorrough resorted to the phenomenon of Supergraphics that developed during the late 1960s and early 1970s as well as some of the works by Venturi and Scott Brown, such as their 1962 Grands Restaurant in Philadelphia.12 Under “Enlarge,” Dean herself addressed the ways in which design techniques of mass production have been appropriated by architects when seeking to render operative the interplay between scalar proportions, volumetric outlines, and product articulation. As instances she saw capitalizing on the graphic, Dean examined Aldo Rossi’s 1983/1984 “Variations on coffee–makers” and two projects by Greg Lynn, the 1999 Ark of the World Museum San Jose in Costa Rica and his 2003 scheme for Sociópolis in Valencia.13 For R.E. Somol, “Logo” makes graphics performative.14 Some of the built examples he used included the 2001 Hagen Island housing development by MVRDV, the 2004 Cottbus Library by Herzog & de Meuron, and the 2005 Shipping and Transport College by Neutelings Riedijk. Echoing his ongoing interest in questions concerning shape, Somol alluded to tactics such as “intensify an element,” “extend the line,” “develop a precise but vague silhouette,” and “saturate with a monotone treatment” for the conception of logo-buildings. “Icons,” as per Jencks’s account, do not lend themselves to be described in terms of graphic procedures or classifiable actions. Rather, they act through metaphor, and their materialization is all the more successful the more diverse personal interpretations they allow for. Along these lines, in his book The Iconic Building, which appeared two years before the Hunch, Jencks had introduced the notion of the “enigmatic signifier,” which designates a building’s “use of precise denotations and fuzzy connotations” in reference to the possibility of insinuating suggestive overtones without falling into either literal figuration or plain abstraction.15 The Iconic Building revolves around the figural associations enabled by the condition of architectural iconicity and focuses on the fundamental determinants of such a condition: the design gestures defining the building’s exterior profile (curves, bellies, animal-like contours, loops, abrupt lines, etc.).

Some of these strategies originated earlier in the twentieth century; it was therefore only a different operative instrumentalization that subsequently emerged. But the degree to which they have proliferated following the Bilbao effect is certainly distinctive of our time. In proliferating while steadily keeping within the purview of the representational break, those strategies have been simply reaffirming the epistemic intensification derived from Learning from Las Vegas.

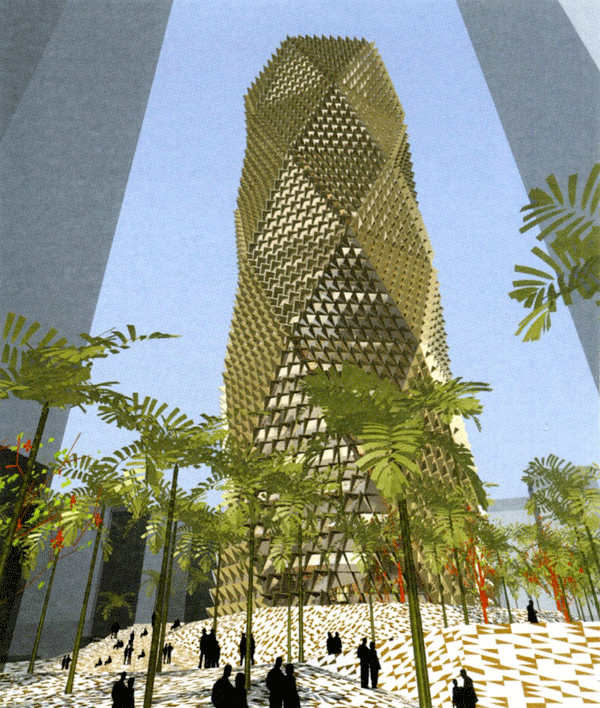

Foreign Office Architects, Special Plan for Cabo Llanos, Tenerife (2003). Source: Foreign Office Architects, Phylogenesis: Foa’s Ark (Barcelona: Actar, 2003), 505.

At first glance, a proposition launched by Alejandro Zaera-Polo around 2005 could be read as a challenge to the representational break. The Spanish architect suggested “deliberately associating an image and an organizational system with a coherent entity as a project strategy.”16 He also called for ideas such as “the consistency between the material and the meaningful” and “the development of the discipline of form with a double agenda, that is, operating simultaneously both as an organizational and as a communicative mechanism.”17 On close inspection, however, it turns out the link Zaera-Polo envisioned between representational character and organizational system only hardened the representational break. On the one hand, the link was merely established a posteriori: it was meant as a tool to communicate projects once they had been finalized, rather than one built into the design process. In this regard, Zaera-Polo spared readers any exhaustive exegesis, himself acknowledging the real purpose of his postulates: “Paradoxically, the most banal and Disneyesque iconography became the justification, both conceptual and financial, for the formal experimentation.”18 On the other hand, by “form” and “the material” Zaera-Polo referred only to the building’s outside, despite his use of terms such as “organizational system,” which seemed to point to the interior.

Consequently, more discontinuities between envelope and internal spatial organization ensued, as evident in the projects that Foreign Office Architects (FOA, Zaera-Polo’s firm with Farshid Moussavi) were proposing at the time. For example, the contortions animating their 2002 Ground Zero proposal—the features enabling the scheme to be described in terms of looking like “castellers”—were applied to the masses of the entire buildings (to their shape) whereas internally they housed the usual stack of floor slabs occasionally interrupted by a few sky lobbies.19 Their 2003 tower project in Tenerife, Spain was made evoke a palm tree, if through an outside view alone. In their 2004 stadium for the Olympic Park in London, it was the configuration of the outer envelope—segmented in a sequence of curved sections—that became the source of a muscle metaphor. Upon peering into it, however, the stadium was pretty much like any other. The spatial disposition structuring the inside of these buildings was not born out of the three-dimensional ethos of the symbolic referent, but rather simply appeared after the fact.20 Therefore, FOA’s work, not unlike the numerous examples offered by Jencks, fell back into the very same representational break, with protocols of signification staying at the level of exterior conditions, and problems of dispositional thinking remaining virtually unaddressed.21

Organization Through Representation

Kenneth Frampton famously associated two trends that he rooted in the commodification of architectural expression: the reduction of architecture to scenography—which he linked to the triumph of the decorated shed—and the pursuit of spatial invention as an end in itself.22 Disentangling this conflation, the contention here is that emphasis on the former (i.e. building-as-representation) has come at the expense of attention to the latter (i.e. building-as-spatial-organization). With image architecture operating relentlessly in tune with the duality of these two aspects as taken to the extreme—with fancy skins wrapping endless piles of horizontal slabs in towers in Dubai and elsewhere, to offer another example—a dynamic underlying what Sylvia Lavin called “the era of representation” has settled in.23 Gehry’s Guggenheim triggered a widespread appetite in cities across the world to build and own imageable buildings. For one thing, this phenomenon is supported by factors mainly of a socioeconomic and political kind, such as financial profit and representational power. For another, imageable buildings tend to embody an acute exploitation of the duality. Which is to say, contemporary socioeconomic and political factors have come to perpetuate this exploitation, and with these conditions in place, architects design accordingly.

One must question then, if it is possible to conjure up an alternative to this status quo centered around the pervasiveness of the common attributes giving rise to the “duck” and the “decorated shed,” since pushing the possibilities of architectural thinking remains a constant demand on the discipline’s historical development. Logically, such an alternative requires a collapse of the duality of building-as-representation versus building-as-spatial-organization, as well as envisioning how this epistemological erasure could operate for the case of imageable architecture. The answer involves thinking spatial organization through protocols of representation.

Pieces of architecture envisaged through this approach possess a number of specific characteristics. Their ornamental pattern on the exterior is part of their internal spatial arrangement. In other words, their identity lies in the synthesis of representational character and spatial disposition; of conditions of imageability and three-dimensional configuration. These conditions do not “symbolize” or “express” anything happening on the inside. Rather, they are the inside. Thus, distinguishing inside from outside becomes meaningless in an ontological sense—as opposed to rhetorically or merely on perceptual grounds, which has been the case historically in architectural tropes such as “interior and exterior getting mixed up,” “both domains flowing into each other,” and so forth. The difference with the “duck” becomes obvious: the duck-envelope symbolizes the function of the building, but its defining qualities have nothing to do with the internal spatial disposition.

Buildings conceived out of this approach may seem to resonate with the modern movement’s outside-as-a-result-of-inside motto, yet by no means do they embody it in the same sense. Modern architects sought to achieve a particular kind of interior-exterior correspondence by treating an independent plane—the façade—so that either program or interior volume (or both) might be legible from the outside. It was about projecting onto the outside wall in order to make it a display of the interior. In contrast, the enclosure of the buildings whose spatial organization has been devised through protocols of representation does not register as an independent element, for whatever is constitutive of their external condition is equally constitutive of their three-dimensional articulation inside.

This essential dissimilarity can also be identified in the process of design thinking leading up to either type of building. In the modernist one, it is usually the interior that makes its way to the exterior, while in the alternative approach two other procedures may apply. In a reversal of the modernist premise, the inside may be the result of an outside whose representational character is defined at the outset—as in a spatial configuration that develops out of a particular ornamental quality or symbolic profile. Alternatively, the whole structure may be thought of as a three-dimensional arrangement with no predefined volumetric boundaries that dissociate it a priori from an external field. In this case, the resulting outside condition is contingent upon the way that such an arrangement manifests itself relative to the specific volumetric envelope that is eventually given—as opposed to it being defined independently, or sequentially after so as to showcase the interior. If in modern architecture the plan was the generator, here it is a particular mode of subdividing space three-dimensionally that provides the originating situation.24

After the modern movement’s advocacy of the façade as a display of the inside, and the intensification of the representational break—faithfully endorsed by Koolhaas’s “lobotomy”—the approach put forth here is one whose instantiations are not easy to track down. If there have been ducks and decorated sheds since at least the twelfth century, the first buildings stemming from thinking spatial organization through protocols of representation comprehensively enough go back only a few decades.25

Architect and theorist Alfred Neumann was a pioneer in transferring aspects from the domain of representation—regarding ornament, in particular—to that of spatial disposition. In his 1969 essay “Architecture as Ornament,” the father of so-called “architectural morphology” elaborated on the analogies between the structural and ornamental properties of two-dimensional crystallography versus those of its three-dimensional equivalent. He sought to prove the potential of the latter to contribute to the question of spatial arrangement in architecture while maintaining the ornamental order distinctive of a crystallographic aggregation. In a statement condensing such “pattern thinking,” Neumann wrote:

If it is admissible to consider ornament as two-dimensional crystallography, it is equally justified to call crystallography and with it architecture a three-dimensional ornament. For architecture is related to crystallography from the space-packing point of view.26

Just as crystallography concerns itself with the regular subdivision of space, space packing deals with the study of specific polyhedra that leave no spaces unaccounted for when placed together in space.27 The complexity of the polyhedra qua spatial units is itself space packing’s object of research as well.28 It was by placing a great emphasis on the problem of the subdivision of space that Neumann set out to recast the nature of space-packed architecture as three-dimensional ornament. Exemplary of this ambition were the Dubiner Apartment House in Ramat-Gan, Israel (1961–63, with Zvi Hecker and Eldar Sharon), and his entry to the Netanya City Hall competition in Netanya, Israel (1964, with Hecker). These buildings were conceived as a grouping of polyhedral cells whose dense aggregational quality, while structuring space, was construed as ornamental.

Neumann displaced architecture’s ontological grounds by equating them with those of ornament, and in so doing triggered the possibility of constructing deliberate links between architectural protocols of adornment—typically restricted to bi-dimensional elements—and holistic formal arrangements. Yet cases like Neumann have been rather uncommon, especially if the same degree of rigor and sophistication is demanded in turning the logic of ornament (or another representational aspect) into that of a full-fledged building’s spatial arrangement. From around the same time, Bertrand Goldberg’s Marina City in Chicago (1959–1964) stands out conspicuously. The radial character of its spatial organization as well as the disposition of the balconies within it appear linked to the fact that the two towers comprising the complex evoke the metaphor of the flower.

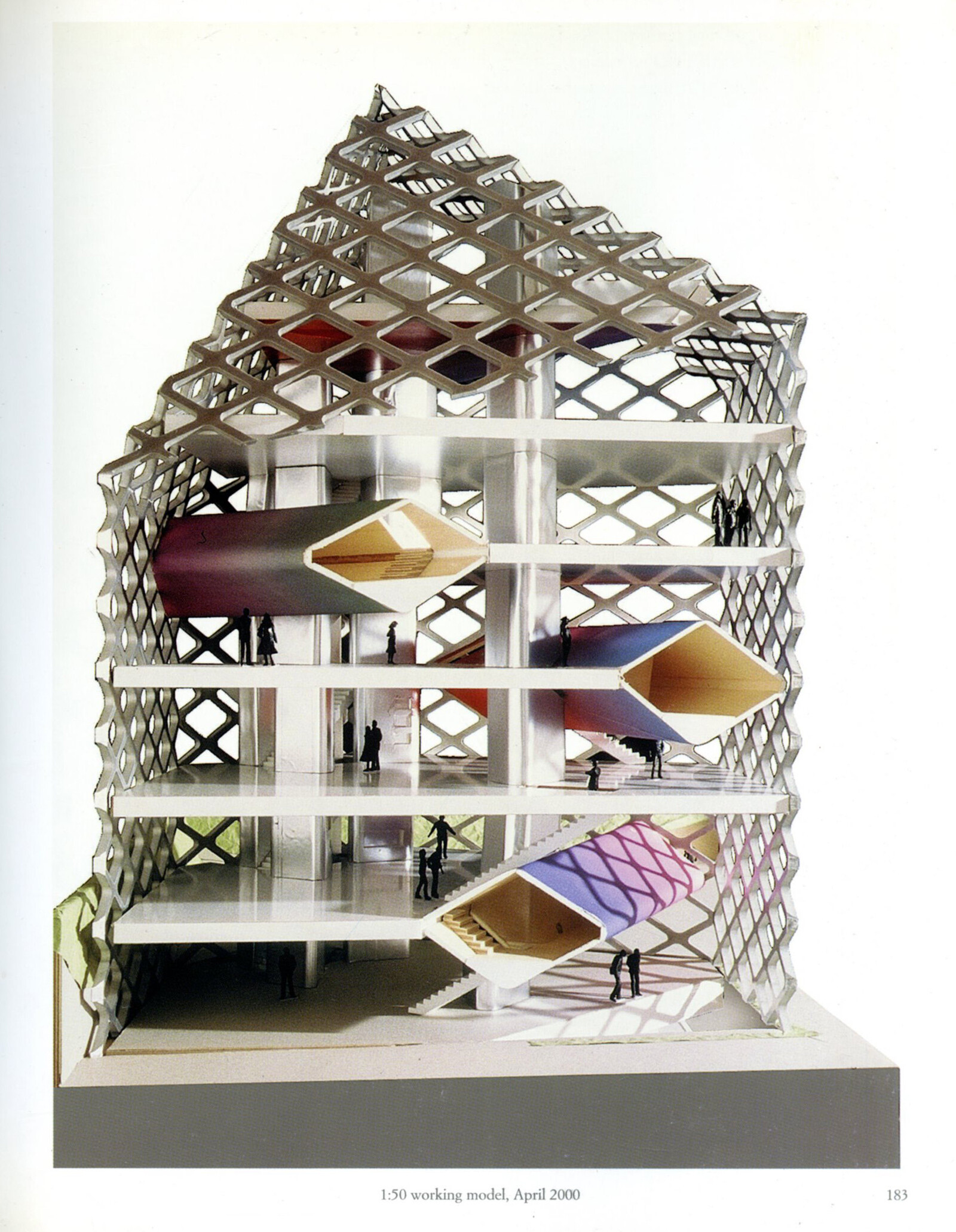

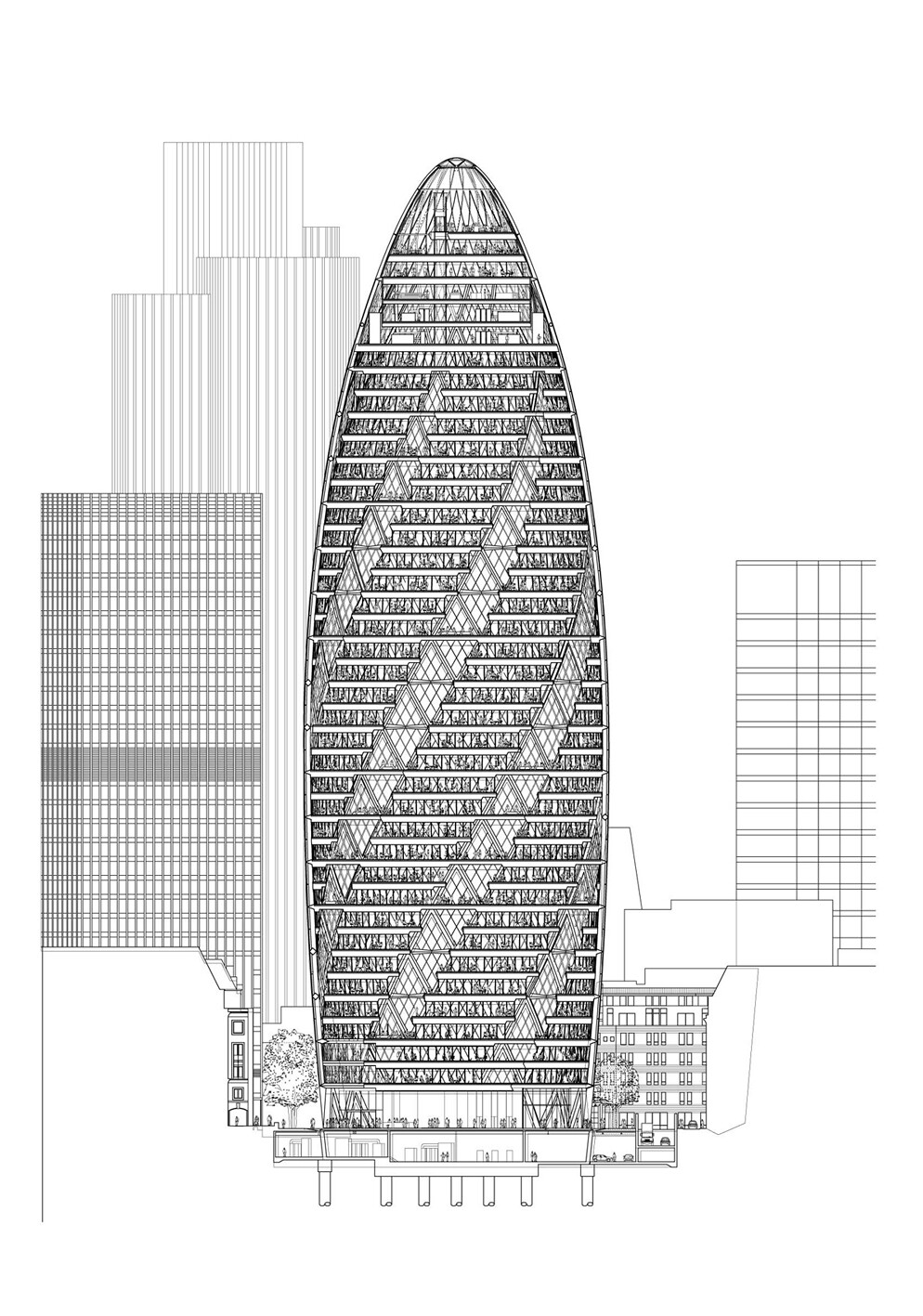

From earlier this century, Herzog & de Meuron’s Prada Aoyama in Tokyo (2001–2003) is another example. The representational character of this building is determined by the diamond-like pattern on the façade, but the pattern is in fact a diagrid structure—a few units of which get extruded horizontally at intervals to create singular programmatic areas that cross and articulate the double height spaces they pierce. Norman Foster’s 30 St. Mary’s Axe in London (2004) also features a notable consistency between imageability and internal configuration. This building challenges the traditional typology of the floor-upon-floor high rise by establishing a spiral sequence of sky courts which, clustered every six floors, create diagonal perspectives across the interior—while representationally, the fact that the shape was reduced to a simple yet distinctive volumetric outline made it open to many possible interpretations.29 What is particularly noteworthy is that both these aspects define one another: 30 St. Mary’s Axe materializes a distinctive relationship between representational character and spatial disposition in the sense of presenting an inextricable bond between its contour being bullet-shaped and the internal spatial arrangement being determined by a succession of spiraling courts. This synthesis is the product of two sets of considerations informing each other: on the one hand, those involving technology, efficiency, and typological subversion; and on the other, questions of symbolism and imageability.

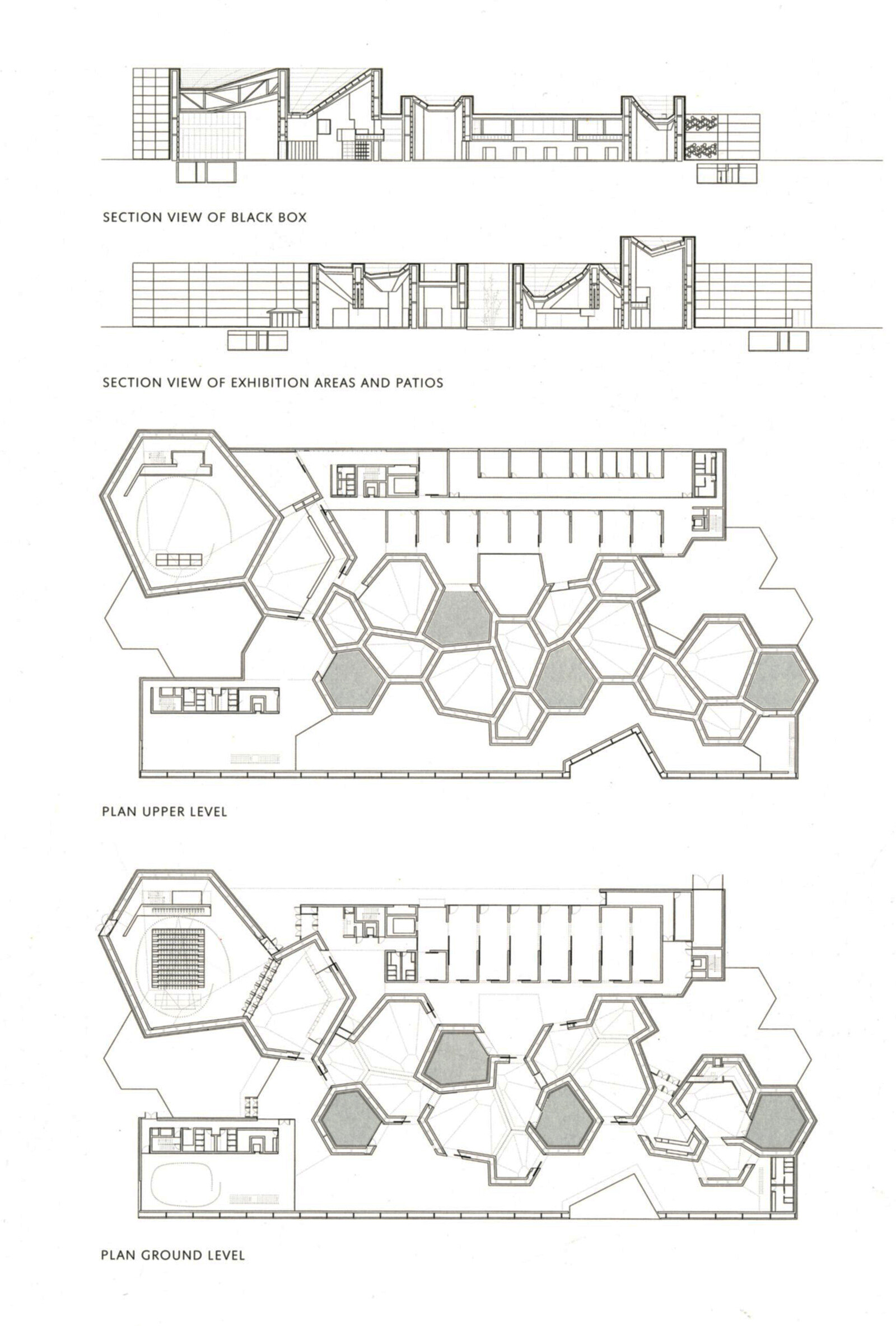

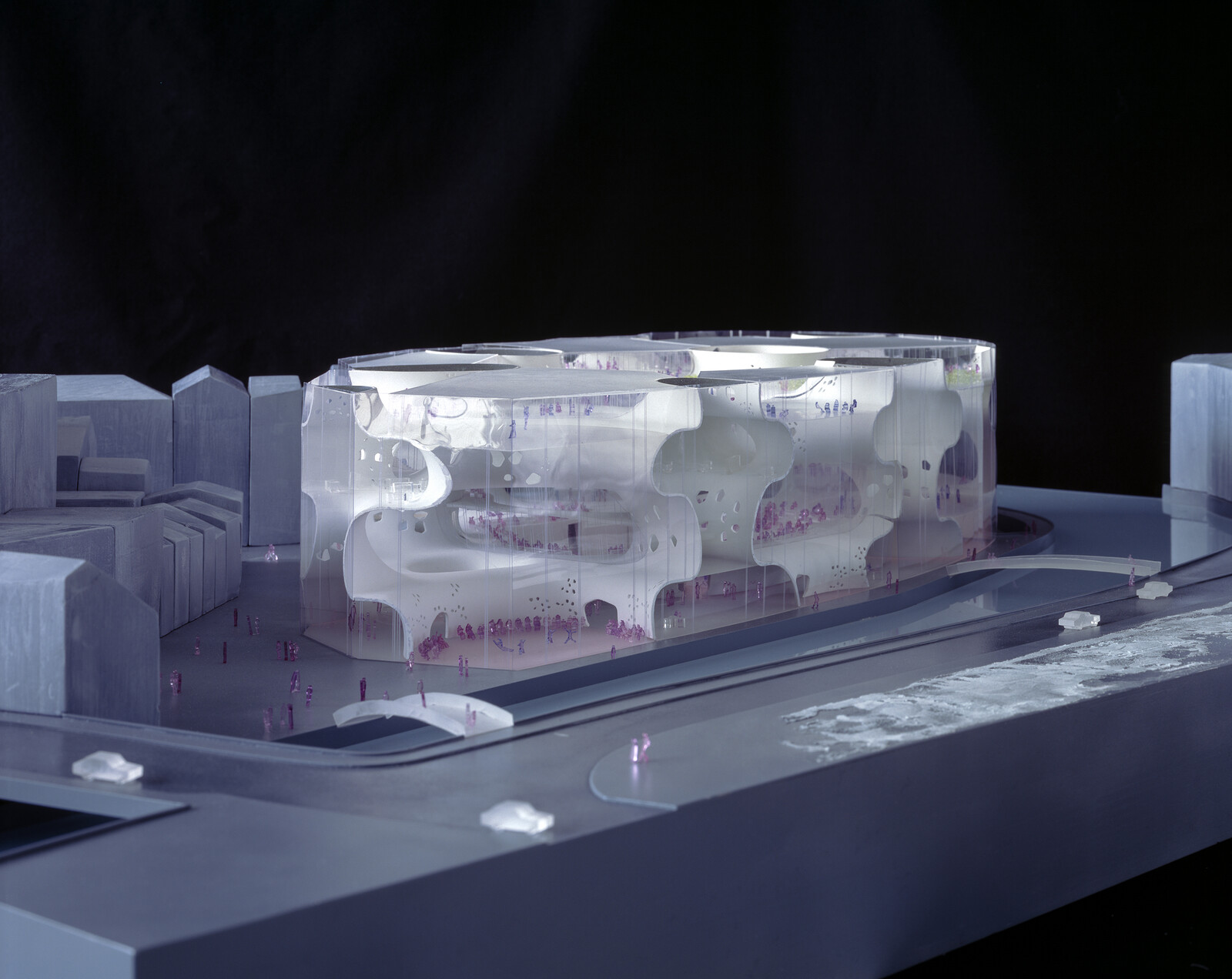

More recently, in 2013, Nieto Sobejano completed a Contemporary Art Center in Córdoba whose spatial configuration is analogous to that of the ornamental patterns characteristic of ceilings in traditional Islamic architecture. Other relevant instances include Toyo Ito’s Taichung Opera House and its predecessor, a 2004 competition entry for the Forum for Music, Dance, and Visual Culture in Ghent, Belgium. The formal arrangement actualized in these buildings stands in direct relationship to the ornamental qualities of sponges.30

Herzog & de Meuron, Prada Aoyama, Tokyo, Japan (2001–2003). Source: Herzog & de Meuron, Prada Aoyama Tokyo, eds. Germano Celant and Miuccia Prada (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2003), 103.

Foster + Partners, 30 St. Mary’s Axe, London, UK (2000–2003). Source: EU Mies Award.

Nieto Sobejano, Contemporary Art Center, Córdoba, Spain (2006–2013). Enrique Sobejano, Fuensanta Nieto, and Ana Pascual Posada, Nieto Sobejano: Memory and Invention (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2013), 230.

Toyo Ito + Andrea Branzi, Forum for Music, Dance, and Visual Culture, competition entry, Ghent, Belgium (2004). Photo: Hisao Suzuki.

Herzog & de Meuron, Prada Aoyama, Tokyo, Japan (2001–2003). Source: Herzog & de Meuron, Prada Aoyama Tokyo, eds. Germano Celant and Miuccia Prada (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2003), 103.

Toward a Critical Imageability

Though mostly unfolding within the paradigm of the representational break and its intensification, the ways in which design strategies resonating at the level of imageability have been developing over the last twenty years bear the imprint of their usage exceeding the sphere of signification alone. For implicit in those strategies is the possibility of their triggering form at a building scale, with this term, “form,” construed, not as “shape” or “mass”—that is, concerning merely the sensory properties of a building as they bear on its outline or envelope quality—but rather as a spatial regime of internal organization, disposition, arrangement. It is precisely through a consistency between imageability and form thus understood that such a paradigm at the core of image architecture can be superseded.

In terms of design, the reason to argue for a link between representation and dispositional thinking is fundamentally heuristic, since it unleashes a distinct capacity to prompt novel ways of conceiving spatial arrangements in architecture as well as the attendant typological and programmatic inventions. In a theoretical sense, the discursive construct around this model gives rise to the realm of critical imageability, one that has the capacity to catalyze alternatives to the representational break, and through it to standard spatial arrangements in architecture, commonly dominated by those of a floor-upon-floor nature. The use of criticality invoked here is therefore dialectical rather than resistant; specifically, dialectical with a constructionist valance.31 It is one that mobilizes the very dynamics underwriting the state of affairs—i.e. the twofold, free-floating condition of the architectural image, both in its detachment from formal arrangements and in its capacity to travel across different realms—in order to subvert that very state.

The fact that institutions and agents in power keep capitalizing on architecture’s qualities of imageability seems to validate this project, which essentially proposes an attempt to turn the answer to demands on those qualities into architecture’s disciplinary advantage. It has become evident that surrendering to the sociopolitical dynamics driving the desires of the contemporary city is naturally leading to stagnation in terms of the discursive content of architectural design and its history, as it reinforces a paradigm that has been operational for quite some time now. Given this scenario, thinking spatial organization through protocols of representation paves a way out of this stalemate without being oppositional: it tunes in to the specific appeals being currently made on architecture—that is, those on its imageability—yet, in doing so, it critically dismantles the duality underwriting the epistemic intensification brought on by VSBI.

All in all, the position articulated here suggests turning the structures underpinning today’s image architecture into something of a critical construct by fostering a particular kind of formal thinking less keen on accidental metaphors than on solid theories of spatial organization based upon protocols of imageability. And it does so by reconciling the two dimensions of building that Frampton considered at odds with one another: “the representational” and “the ontological.”32 For critical imageability rests on the possibility that the former may be instrumentalized in order to make substantial contributions in the realm of the latter (insofar as spatial organization determines the very being of a building; its kernel, its ontological matrix).

By extension, this approach offers an alternative to the current bent of postmodernism, since it targets the representational break that this bend shares with image architecture more generally. In fact, it hints at a larger claim concerning the sidestepping of postmodernism altogether. Namely, postmodernism has typically been characterized along two axes: on the one hand, in relation to theatricality (i.e. historicism and the phenomenon of the building-as-icon); and on the other, through questions of interiority (i.e. autonomy, deconstruction, and digital design). Seeking a bond between representational character and spatial disposition entails generating interiority—insofar as such a disposition acquires a logic of its own—through theatricality, thereby rendering void the divide between the two categories. In other words, the effective hypostatization of protocols of meaning in general—and of ornament, in particular—in their transference from the realm of signification—or in some cases from the merely aesthetic—to that of formal organization, constitutes an epistemological shift that can no longer be framed within postmodernist agendas.

Charles Jencks, in a debate held at Columbia University on October 26th, 2005.

The first two Chicago Biennials, UCLA, and discourses around practices in the Belgian and Italian scenes can be cited here as representative examples.

See Charles Jencks, The Iconic Building (New York: Rizzoli, 2005).

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977), 87.

The phrase “representational character,” as Sylvia Lavin pointed out, may be made assimilable to Kevin Lynch’s “imageability” and Charles Jencks’s “iconicity.” See Sylvia Lavin, “Practice Makes Perfect,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 106.

Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, 87.

Ibid.

Ibid., 105, 113.

I am adjusting the definition of the term “imageability” to the case of architecture. The original one alluded to “any physical object,” though it was intended specifically for the city. See Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1960), 9. Also, it is worth comparing my redefinition to Anthony Vidler’s use of the term when alluding to Reyner Banham’s discussion of the concept of “image” in his The New Brutalism piece. See Anthony Vidler, “Toward a Theory of the Architecture Program,” October 106 (Fall 2003), 70.

Due to the significant volume of visitors attracted from outside the Basque region, the museum generated, in as little as two years, as much money as to finance another four Guggenheims. This economic dynamic seduced an overwhelming amount of foreign entrepreneurs that went to the Northern Spanish city to invest, which greatly boosted the fortune of the region. The relevance in the media, however, turned Bilbao’s Guggenheim into something more than just a local success. For a more elaborate discussion on the impact of this building for the city of Bilbao, see Jencks, The Iconic Building.

See Penelope Dean, “By No Means Representation,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007): 14–15.

See John McMorrough, “Blowing the Lid Off Paint,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 64–73.

See Penelope Dean, “Blow-Up,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 76–83.

Robert Somol, “Green Dots 101,” Hunch, the Berlage Institute Report 11 (2007), 28, 34–35.

Jencks, The Iconic Building, 84, 86. Jencks used Daniel Libeskind’s proposal for the Ground Zero to illustrate this notional construct.

Alejandro Zaera-Polo, “La Ola de Hokusai,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 80. My translation and emphasis throughout.

Ibid., 86.

Ibid., 80.

The “castellers” are human towers built traditionally in festivals at many locations within Catalonia (Spain).

Zaera-Polo’s piece, along with two related lectures he had previously delivered at UCLA and Princeton in 2004, prompted some severe criticism. The most penetrating was put forward by Jeff Kipnis, who talked about “literal ways of architectural signification,” “the flirtation of FOA with vulgar symbolism,” and “withered terms {in reference to the use of ‘metaphor’}” when referring to the propositions of the Spanish architect. He added that Zaera-Polo had confused “the two referential possibilities of (every) architectural form,” namely, the pictorial—as the realm of representational effects mimicking a reality from a domain other than architecture—and the significative—as that which, including the symbolic, alludes to the use of formal and architectural conventions that are historically and traditionally charged with the view to conveying agreed associations and interpretations (e.g. the conventions of classical language). See Jeff Kipnis, “Lo Que Aquí Conseguimos Necesitamos Es ¡No Comunicar!,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 94–98. My translation. Along the same lines, see Sylvia Lavin, “Conversaciones Acompañadas de Cocktails,” Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme 245 (April 2005), 88–92. Kipnis further argued that, in fact, the pictorial, qua traditional effect in sculpture, has no equivalent in architecture, where it can only take place as ornament—that is, in reference to the part, but never to the whole. Here is where I part with him, for this essay, as shall become more apparent further on, contends the possibility of the exact opposite: that ornament may be mobilized in its organizational properties so as to structure the whole of a building. This is precisely the way in which the figural, whether as “pictorial” of “significative,” bears potential for architecture beyond its effects in the realm of the representational—i.e. insofar as it can enter that of spatial articulation. In the same piece, Kipnis posed the question whether it is possible to conceive of a kind of figuration in architecture that escapes representation, in the sense of eluding the significant effect. While I see my argument as the beginning of an answer to this question, I will not elaborate here on how that is the case. Nor will I discuss how such an argument relates to other aspects that Kipnis associates with the non-significant figural, such as the fact that it is supposed to involve architectural traits that are disciplinary specificities in themselves, and the ways in which these, by avoiding imitation, can only be rooted in the figurative history of the discipline of architecture.

The phrase “dispositional thinking” is used here to designate thinking processes in architectural design dealing with questions of three-dimensional spatial disposition. Understanding retrospectively that “The Hokusai Wave” was but a prelude to his subsequent Politics of the Envelope project (begun in 2008) would be another way to show that by the mid-2000s Zaera-Polo was mostly concerned with questions of external envelope. See Alejandro Zaera-Polo, “The Politics of the Envelope: A Political Critique of Materialism,” Volume 17 (Fall 2008), 76–106. The ideas he promoted then ought to be seen as the initial manifestations of the increasing pragmatic valance of his thinking. Being preoccupied with getting his projects realized while trying to maintain a certain experimental quality for them, Zaera-Polo started to focus more and more on questions of communication while progressively giving up on the interior. Exemplary of this shift was FOA’s John Lewis department store in Leicester (2000–2008), a box-like construction whose skin is a glass façade printed with embroidery patterns. This building is considerably easier to get built than, say, a Yokohama Terminal, but it is also not nearly as sophisticated an architectural project. Let us recall that the central premise in The Politics of the Envelope was that the architect had largely lost his say in questions of spatial organization, and therefore he should focus on designing and theorizing the envelope alone.

Kenneth Frampton, “Rappel à L’Ordre, the Case for the Tectonic (1990),” in Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture, an Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995), 516–520.

Lavin, “Practice Makes Perfect,” 109.

Elsewhere I have written about one particular species of architecture arising from thinking spatial organization through protocols of representation: the sponge building. See José Aragüez, “Sponge Territory,” Flat Out 2 (Spring 2017), 32–36. This species of building displays a series of features particular to it—such as a certain geometric kernel that generates a specific sequence of spaces—while materializing the general principles laid out above.

For historical examples of ducks and sheds, see Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas, 104ff.

Alfred Neumann, “Architecture as Ornament,” Zodiac 19 (1969), 90–98.

For a recent elaborate study of the role of space packing in Neumann’s architectural thinking, see Rafi Segal, Space Packed: The Architecture of Alfred Neumann (Zurich: Park Books, 2018).

For an extended definition see Keith Critchlow, “Closepacking,” Zodiac 22 (1972), 172–178.

See Madelon Vriesendorp’s drawings in Jencks, The Iconic Building, 186.

See Aragüez, “Sponge Territory.” The Taichung Opera House is more relevant here than another project by Ito brought up more often when questions of representation are at stake: the TOD’s Omotesando building in Tokyo, completed in 2004. Here a link exists only between the ornamental qualities of the façade (its looking like a tree) and its properties as a load-bearing structure, while the rest of the building is a rather conventional floor-upon-floor articulation. For an insightful take on the decorative character of structural envelopes in contemporary architecture, see Nina Rappaport, “Deep Decoration,” 30/60/90 10 (2006), 95–103.

The qualifier “constructionist” is here used to invoke a recent tendency in theories of critique within the Humanities and Social Sciences whereby the final result of criticism is not simply an oppositional, negative view of the current state of affairs, but rather a set of directives toward the construction of a parallel regime of reality. This regime is conceived as the result of reconfigurations and new assemblies of the constituents of the existing reality within the targeted domain, for instance that of perception, signification, and politics, to mention a few. For a discussion of the possibility of a constructionist criticality in architecture at the intersection with this larger tendency in the Humanities and Social Sciences, see José Aragüez, “On Architecture’s Metacriticality,” in Chris Brisbin and Myra Thiessen, The Routledge Companion to Criticality in Art, Architecture, and Design (Milton Park and New York: Routledge, 2018), 167–178. Two texts essential to the larger trend include Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2010), and Bruno Latour, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern,” Critical Inquiry, no. 30 (Winter 2004), 225–248.

Frampton, “Rappel à L’Ordre, the Case for the Tectonic (1990),” 516–20.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)