Nikolaus Hirsch We are interested in the contradictions and potentials of today’s architectural practice, and in speculating on what this practice might be in the future. How has your own practice and your way of thinking and working changed as an effect of the deep societal, technological, and economic changes that have taken place over the past decades?

Juan Herreros The question of what kind of architect was and is possible has been crucial in the different forms of offices I have run over the last three decades. I started my practice in the late 1980s, at the moment when Spanish architecture began to explode onto the international stage. In those years, global interest in Spain and its architecture matched the optimism that accompanied the formation of our democracy, the construction of a new society and, of course, economic prosperity. But all progress is in part fiction, and at the turn of the millennium I began to point out that life in Spain had become so expensive that every young couple, even with a good salary, couldn’t do much more than live day-to-day. At this same moment, the architectural scene was divided between public buildings of high design quality, a neoliberal architecture of commercial buildings with no more pretension than to place their products on the market, and a social architecture that, although it was an enormous initiative, failed to overcome the urban segregation that was inherited from earlier times.

NH How was this reflected in your practice?

JH At the beginning of the 2000s, I split my former office with Iñaki Ábalos, and my professional and pedagogical practice radically changed. I moved my interests from technology, understood as construction systems—which was one of the main things that gave rise to the international prestige of Spanish architecture—towards an understanding of technology as political and social instruments. The existing city and the urban role of every building was the topic at the top of my agenda, both in the office and academia. My idea was that if European cities are our greatest patrimony, but are not finished, it would be better to correct rather than expand them, meaning re-inventing, re-programming, re-densifying, re-naturalizing them. Then, for many reasons I also wanted to work in a much more collaborative and transgenerational way. Conversation—with our team, consultants, clients and friends—is for me, today, the most significant instrument of design. Following from that, and reflecting on my own experience, I began conducting research into the design of practice, the idea of architectural practice itself as a project.

NH It’s interesting how you talk about the practice as a project in itself in relation to collaboration. Architects traditionally cultivate the idea of the architect genius, as the one person who knows everything and all the others as good experts in their respective fields, but slightly ignorant regarding the overall concept. The architect was the one who put the pieces together, as one who had a teleological view of the project. Yet today, it becomes more than obvious that many experts, consultants, and engineers have entered the stage. Think of Cecil Balmond, Hanif Kara, Jürg Conzett, Jun Sato—many prolific projects today are simply unthinkable without the contribution of structural engineers. Is the architect still the person who’s the mastermind in these complex projects?

JH You’re completely right. The process of design of big projects has become incredibly complex and evolves a huge number of people. In this context, the role of the architect—who is not always at the top of the pyramid—and the concept of collaboration need to be revisited. The comparison between architects and orchestra conductors or film directors doesn’t work anymore. With the new conditions that arose during and after the crisis, the energy needed to keep the control of everything has been dissolved into thousands of conversations, emails, Skypes… Our work today is closer to a DJ, using fragments, identifying moments, confronting inputs and information from very different people and knowledges.

NH What is different today?

JH The architect is still the one compressing and synthetizing all of this information and complexity, but they are not the only one making decisions. Likewise, the role of engineers and collaborators is no longer just to solve the problems that architects invent. Our Ágora Bogotá center, for instance, was built with no air conditioning, just cross ventilation. The installations of the Munch Museum, similarly, were scattered inside the structure to avoid basements. We could only do these types of things with all of the partners working together. Something similar has happened to the words you mention: is not architecture, and it’s not engineering; it’s an amalgam of concepts and know-how. When the discussion is in another field, the architect needs to be willing to listen to others and even step aside, letting others take the floor. The brilliant part of these collaborations is not related to the expertise of others that we don’t have, but is rather the ways of thinking and operating that we can learn: the pragmatism of engineers, the obsessive conceptualization of artists, the rigor of geographers, can inform our own systems of thinking and work. And I hope that the flexibility, the collaborative spirit, the use of history, and the concept of the project inherent to architecture can inform these other disciplines that we work with as well.

estudio Herreros, Communication Hut, Gwangju, 2011. Photo: Nathan Willock.

Nick Axel If this is the moment that architects are finally learning from others and finally collaborating in a more, let’s say, authentic or real way, I would say that it’s not necessarily for will or for want: it’s by necessity. Collaboration is the only option today, not just because of economic demands, but also because of legal demands, and even, at the most basic level, because of the tools we work with. We might be learning from art, but we’re also learning from the organizational scientists who are designing our software. The tools of the architect are structuring and articulating the way that we collaborate with others—and vice versa.

NH BIM is one the most striking phenomena in this respect.

NA You said that you started by looking at construction systems as technology, and then political systems as technology. How have these types of software and technical systems that architects use on a daily basis to orchestrate this collaborative process influenced your practice?

JH There is often nostalgia for systems where design intent can be expressed more fluently that what BIM technologies offer. But even if you don’t like BIM, it is important that these tools are creating a more common base of technical knowledge that is independent from the location and the size of practices. The irony is that the tools that were invented to facilitate the management of large, corporate offices—and which neoliberal economies love—can allow small practices to be competitive and operate worldwide. Sharing technologies means that all the offices have the same resources, can bring the same expertise, and work from different locations without opening expensive corporate branches. In this sense, small offices can be more flexible and offer a more personalized service. Like boutique lawyers in contrast to big corporate law firms, clients can now choose a small office instead of insisting on calling the same big names. If you look at what’s been happening in the professional landscape of New York over thee past fifteen years, you can see that a bunch of small offices have an international practice with interesting clients, which I really think is thanks to the ability to use the resources of big corporations but without needing to become one.

estudio Herreros and Mallol y Mallol, Office Tower, Panama City, 2010. Photo: Fernando Alda.

NA What sort of effect does this have on the nature of architectural practitioners and firms like yours?

JH In my office you’ll find one group of people working on one project sitting next to another group of people working on another project. Different layers of dialogue are taking place at the same time, between both people working together in the same space but on different projects, and people working on the same project but who are physically distant. This allows our young collaborators to be part of sophisticated conversations and feel that they have something to bring to the table. We’re definitively moving beyond the hierarchical model of training architects through a progressive complexity of the tasks they do. Our experience has taught us that very young and relatively unexperienced people can play important roles in decision-making processes. Decisions are being made today less in the privacy of the Moleskin and more by meeting with people.

NH Do you tell your students not to have sketchbooks anymore?

JH Well, they can have one, sure, but I insist that they cannot fetishize their sketches if they want to progress. In my case, I don’t use them anymore, and prefer to work by expressing concepts and reacting to their interpretation and representation by my team. Maybe this is because the thousands of hours I’ve spent at my students’ desks reviewing their work!

NH The new collaborative technologies that you describe seem to make it possible to work on a more global scale. Your recent projects are located in extremely diverse geographies, from Norway to Colombia, Morocco, Panama, and France. Do these technologies and the organization or distribution of work have an impact on what is usually called the local or the contextual?

JH Every project we have abroad is based on our collaboration with a local team. It’s the conversation with these people that give us clues to understand the reality and everyday life of the places where we work and allows us to re-describe them through design. The role of the foreign architect is the one of the observer. Locals describe their places as unique, but also tend to look down on certain potentials because their proximity to them. The global architect, being local in many places and using dialogue as instrument of design, can reconfigure the ingredients of these realities in non-obvious ways, reveal local aspects that might not have been appreciated otherwise. This is why architecture made by sensitive foreigners can have a surprising effect where locals can identify themselves and say “yes, this is me.”

NH This is also, in a way, a very old question. Le Corbusier was probably one of the first really global architects. And over the past few years, for instance, in Chandrigarh, these Indian collaborators have resurfaced. Suddenly one understands that, well, not everything is 100% Le Corbusier. Many architects who work abroad have local architects, which are seen, or even treated as if they are on a lower level, like the old figure of the engineer solving the architect’s problems. But I could imagine different mechanisms opening up in the future. Maybe through certain technologies, be they social or political, or a computer program, it could become possible to go beyond the slightly simplistic of model of import/export.

JH In our case, we tend to work with one of two kinds of local offices, either senior experienced designers or young motivated colleagues. But we never treat them as subsidiaries, as collaborators for merely the bureaucratic or legal issues that you mention. We want them to be open minded and bring their knowledge and culture to the table. Emails, Skype, short videos sent over WhatsApp, and other communication platforms are part of our everyday practice, not unlike the fax machine was when I first started my practice in the 80s. My partner Jens Richter and I, together with our clients, are an active part of this culture of real-time information sharing. In small commissions, like the refurbishment of the Malba Museum in Buenos Aires, or the Communication Hut in Korea, or even in not-so-small projects like the office tower in Panama, we let the local, young architects drive the construction, adapting the project to the existing constraints and technologies. This means that our effort is spent in preserving the concept, but not necessary in guaranteeing that it will be built exactly as it was drawn and detailed in Madrid.

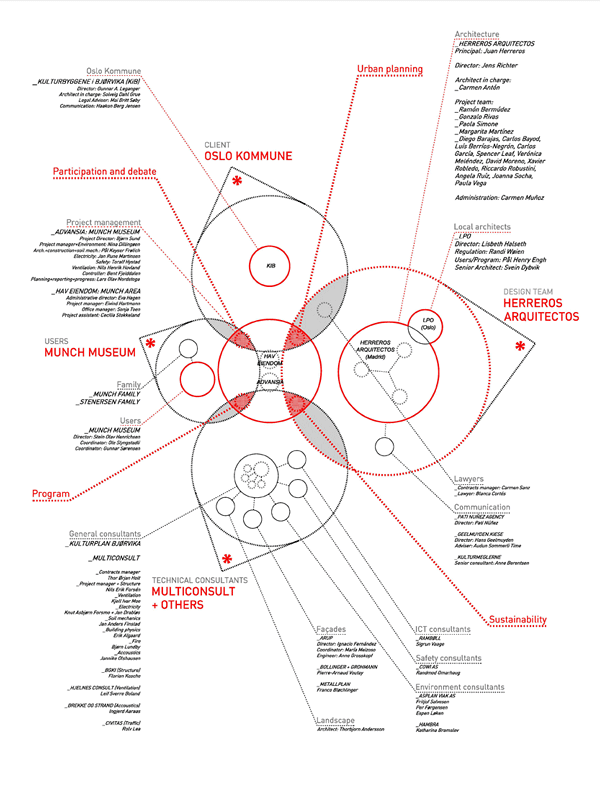

Collaboration diagram of Munch Museum project, published in Aftenposten, May 27, 2010.

NA The impression you’re giving is that the way we work and who we work with ultimately determines not just what our architecture looks like, but what it means and what it does in those places. That certainly complicates the role, the agency, and the voice of the architect, but it also, at the same time, expands it quite significantly. I think it’s quite optimistic: this distribution of agency, opportunity, and responsibility.

JH Critical optimism is a commitment for me. Without it, some everyday difficulties of our profession would be impossible to overcome. The Munch Museum competition in Oslo that we won years ago is a great example of this. The democratic processes in Scandinavian countries can be really complicated, and we didn’t have the resources to afford being so exposed and to defend the project in front of four million inhabitants of a country. But after discussing the social content of these processes with many colleagues, with journalists, and with citizens, I learned that I didn’t really have to convince everybody. I didn’t need to come to demonstrate how wonderful our ideas were. But I also had to realize that, even having won the competition, our design was not finished; that the design process was open, and that the decisions made at my office in Madrid now were subject to review in a political arena. When we demonstrated that we were ready to listen, to reconsider the project, to understand that we had two clients—both the City of Oslo and its inhabitants—all actors came to the table to work together. And the project noticeably improved! Construction is currently about 80% finished, and we don’t have the visibility in the media that we have had in the past. This is because the building is not ours, but is property of the people. We’re just the architects.

NH In a traditional understanding of authorship, what you describe would sound like the project had been comprised. But there might also be a certain intelligence in compromise, because maybe some of the critiques are actually quite good; maybe I didn’t know 100% in advance.

JH Absolutely. Most of the changes we did to the project were more operational than architectural, and the program of the building became more social and diverse. The objections that we were more concerned about—those related to the tectonics of the building like materiality, shape, or height—were resolved through dialogue, by involving the audience in our narratives and using representational tools accurate to their concerns. Architects’ narratives and drawings construct a private language that is quite inaccessible for anyone beyond a jury of architects. In our everyday practice, communication with clients and all the others agents involved in complex projects demands that we explain the same concepts to different audiences. Taking this as a design operation in and of itself has built the character of our office. It is not about mediation, but about understanding that any confrontation is an opportunity to make the design fit better to reality; to make it more feasible.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture. This interview took place during the e-flux conversation series Practice at Milano Arch Week 2018, held at the e-flux Teatrino pavilion designed by Matteo Ghidoni—Salottobuono, made with the help of the Friuli-Venezia-Giulia (FVG) Region and by Filiera del Legno FVG (with the coordination of Regione FVG and Innova FVG).

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)