We’re Solarpunk because the only other options are denial or despair.

—Adam Flynn1

By now, dystopia may have become a luxury genre. Indulging in miserable future scenarios is not something everyone has time for. William Gibson recently repurposed his own adage, “the future is here, it’s just not evenly distributed” to say that “dystopia is not very evenly distributed” either.2 For most, the dystopias the privileged entertain themselves with are old news. In the current political landscape, “when we are all living in the shadow of at least half a dozen wildly science fiction scenarios,” to quote Gibson again, and while Hollywood harps on every version of paranoia to construct a thousand dystopias according to formula, dwelling on dystopia could be seen as downright lazy.3 Along with the resources to sit around and ponder the future of humanity, shouldn’t there come the responsibility to invent actionable proposals as opposed to cautionary tales?

Enter the coalescing movement called Solarpunk. In a 2015 blog post titled “Solarpunk wants to save the world,” writer Ben Valentine summarizes: “Solarpunk is the first creative movement consciously and positively responding to the Anthropocene. When no place on Earth is free from humanity’s hedonism, Solarpunk proposes that humans can learn to live in harmony with the planet once again. Solarpunk is a literary movement, a hashtag, a flag, and a statement of intent about the future we hope to create.”4

The first stirrings of Solarpunk emerged online around 2008, with a noticeable expansion around 2014. At least until now, its dispersed internet origins have mostly kept it from a single authoritative definition or decisive political bent. Some Solarpunks invoke the speciated futures of Donna Haraway and the disaster utopias of Rebecca Solnit, while others say their ideals fit squarely within the “wider tradition of the decentralist left”; some cite the sci-fi canon of the New Weird or Cli-Fi (climate fiction), one claims “post-nihilism,” and a recent book adds dragons to the mix.5 While this diversity of vision is the whole point, one also finds mention of the “core community of stewards who know who they are.”6 Like many born-digital movements, especially those tolerant of anonymity, Solarpunk grapples with what inclusivity means in practice. If everyone’s responsible for it, no one’s responsible for it, too.

As “a movement, a hashtag, a flag,” Solarpunk aims to transform science fiction into science action. An emerging aesthetic sensibility undergirds and drives this impulse. As a genre style, Solarpunk’s visual representation is distinctly architectural and infrastructural: while many bloggers emphasize the importance of the “local,” it is necessarily global in concept. Awareness of planetary-scale environmental destruction is precisely where it derives a sense of urgency. In the face of perceived crisis, Solarpunk demands constructive, instructive fictions. Fictions that are not shy about their intended feasibility.

Stories of science fiction presaging the future are legion, from Arthur C. Clarke’s satellites in geostationary orbit to Minority Report’s movement-controlled interfaces and Gibson’s cyberspace (though the way the word is typically used is not really true to his concept). These myths are often invoked as some form of oblique validation of the genre via authors’ oracular prowess, which itself is a dubious way to evaluate a work of art. In truth, of course, fiction and reality always reciprocally influence each other, they intertwine and merge. “Science fiction is an ouroborous,” writes Claire L. Evans.7 And yet prediction differs from plan. In general, Solarpunk desires the propositional, and to do so it leans toward the positive, the optimistic.

Several popular science fiction authors express Solarpunkish convictions, whether consciously aligning themselves with the term or not. Neal Stephenson founded Project Hieroglyph in 2011: “an initiative to create science fiction that will spur innovation in science and technology.”8 In an essay describing the project, often referenced as a core Solarpunk text, Stephenson laments the lack of large scientific leaps over recent decades, arguing that—for all the Silicon Valley talk of disruption—real progressive innovation has been largely stalled by corporate and academic decision-making aimed to minimize risk. “Where’s my donut-shaped space station? Where’s my ticket to Mars?”9

Along with others, like David Graeber, Stephenson believes the current paucity of long-promised techno-miracles that could revolutionize society is not for lack of technological capability, but for lack of collective imagination and organization.10 The collective ability to envision better futures has been dulled by the structural inhibitions of the only institutions with the resources to make big things happen. Science fiction, Stephenson says, can help.

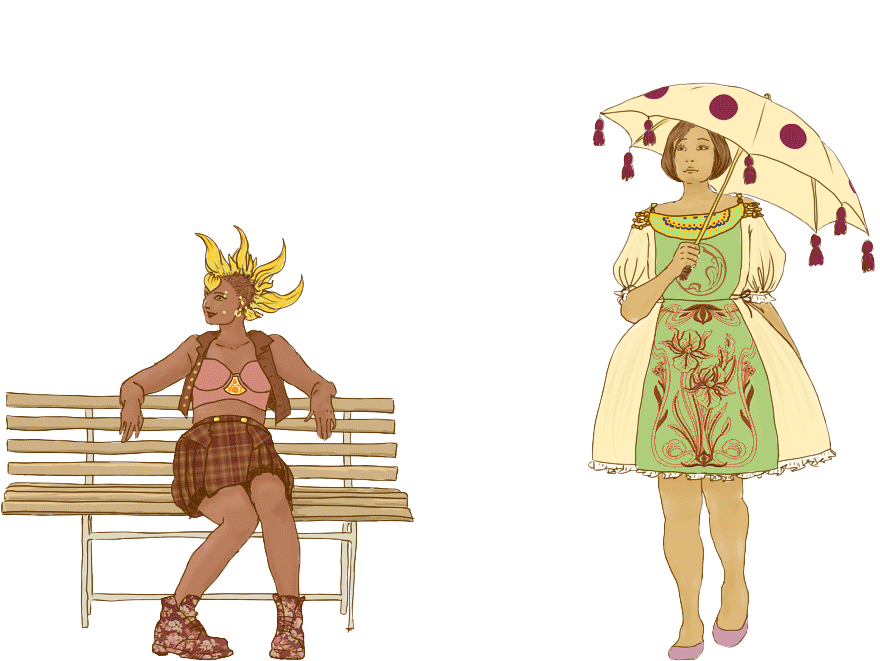

Artwork by Owen Carson.

Artwork by Miss Olivia Louise.

Artwork by Imperial Boy.

Artwork by Miss Olivia Louise.

Artwork by Owen Carson.

Who or What is Solarpunk?

Like its genre predecessors, Steampunk and Cyberpunk, Solarpunk is reliant on an aesthetic that extends to architecture, design, fashion, and art. One debate that crops up in comment sections is about whether Solarpunk is really a political movement or “just” an aesthetic genre. But of course these are not oppositional at all, and the aesthetics attached to the movement can work both for and against its explicit political aims.

While allowing for the plurality and contradiction of a still-emergent phenomenon, and without making assumptions about authorship, dominant aesthetic strands are possible to identify. In a widely shared 2014 tumblr post that has been debated but is nonetheless emblematic, user Olivia Louise described her Solarpunk vision:

Natural colors! Art Nouveau! Handcrafted wares! Tailors and dressmakers! Streetcars! Airships! Stained glass window solar panels!!! Education in tech and food growing! Less corporate capitalism, and more small businesses! Solar rooftops and roadways! Communal greenhouses on top of apartments! Electric cars with old-fashioned looks! No-cars-allowed walkways lined with independent shops! Renewable energy-powered Art Nouveau-styled tech life!11

In its willful naiveté, this ornamented vision is inflected with nostalgia for an imaginary, bygone time when tech was tinkerable and free from mass production and standardization. Broadly speaking, this imaginary past belongs to an Arts and Crafts lineage that fetishized the artisanal and the DIY, often on the part of hobbyist upper classes with too much time on their hands.

Deployed today, this choice is a pointed rerouting from the clean, steel-and-glass, corporate universe hawked by technologists as the way “the future” looks (for rich people)—that evil sleekness of our techno-overlords. Olivia Louise explains: “A lot of people seem to share a vision of futuristic tech and architecture that looks a lot like an ipod—smooth and geometrical and white. Which imo [in my opinion] is a little boring and sterile, which is why I picked out an Art Nouveau aesthetic for this.”

From this post and others like it, one gets the sense that Solarpunk’s aesthetic is partly a negative one, defined by what it needs to avoid: Apple’s white-box futurism on one end, and on the other, scary anarchist hackery—as in, the non-utopian possibility if the order of production breaks down. Solarpunk neither wants to fantasize about the Dove-soap-commercial whiteness of the wealthy space settlement in Elysium (which looks a lot like Apple’s Cupertino HQ) nor the wretched, biohacker-ridden, reggaeton-pumping Los Angeles the movie depicts on Earth below. Between the horror of total technological white-box opacity and that of total technological transparency, this particular version of Solarpunk finds a semi-transparent, stained-glass solar panel.

A Steampunk mantel clock by Roger Wood, part of a 2010 exhibition titled “Steampunk, Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry” at the Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation in Waltham, Massachusetts.

The possible drawback of avoiding these two problematic poles is winding up with a form of nostalgia. In this regard Solarpunk shares a patch of ground with Steampunk, whose stylistic hallmark in the tradition of early authors like H.G. Wells and Michael Moorcock is Neovictorianism. A computer appears in nineteenth-century London; a tophat-wearing engineer time-travels to the present day; swashbuckling ethernet sailors rescue goggled damsels. Steampunk is fascinated with technological anachronism, which often can’t help but implicate other, more obviously problematic anachronisms.

Many have argued that Steampunk tropes indicate a thinly veiled desire to return to a world order where able-bodied white guys were unburdened by housework and free to be heroes. This was also a world in which leaps in industrial technology enabled European domination through colonial expansion. In other words, it’s difficult to conceptually dissociate the “steam” by which that era powered empire and patriarchy from the subversion claimed by the “punk.”12

Others argue that, while Steampunk displays blatant nostalgia, it does so with a “postmodern” twist; irony or even satire from a contemporary vantage point is often built into the narratives.13 To be sure, some Steampunk literature weaponizes genre conventions and others succumb to them; some reify and others critique. But critique becomes a complicated claim, as the genre’s aesthetic hallmarks have become clichéd lifestyle tropes. Although Steampunk champions DIY tech and reclaiming the means of production, its aesthetic is now a distinct consumer niche. As counterculture guru V. Vale put it, while Steampunks love the DIY wrought-iron aesthetic, “not many people have actually learned welding.” Why would you, when “Hot Topic sells goggles”?14

Although Steampunk glorifies technical skill in theory, the sciency parts are often impractical or impossible. “Unlike the inscrutable hard drive of an iPod, you can see wires and coils, cogs and gears exposing this device’s inner workings. [But these] are merely an aesthetic revelation, not a technological justification.”15 Solarpunk is differentiated by precisely the technological realism that much Steampunk lacks.

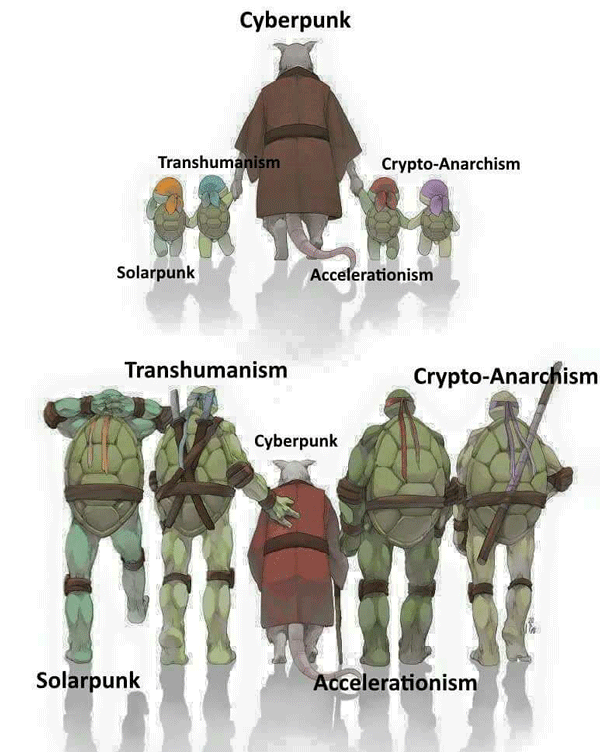

Toward this distinction, Solarpunk highlights contemporary crises. While Steampunks could afford be dilettantes, Solarpunks anticipate necessity: you’ll have to learn to weld when factory production inevitably breaks down and the flood waters rise. In this sense it bears similarities to its more recent cousin, Cyberpunk (discounting, for the moment, seapunk, dieselpunk, atompunk, teslapunk, splatterpunk, spacepunk, cattlepunk, and what Bruce Sterling suggests all contemporary sci-fi should be called: nowpunk). Cyberpunk turned away from nostalgia and undermined technological progress narratives, “introducing as it did the corporate dystopia and a strong sense of class struggle.”16

Solarpunk intends to wrench science fiction from both Steampunk’s magical tech fantasies and Cyberpunk’s tech-gone-wrong. If the energy substrate of the Steam era was coal, and that of the Cyber era was oil, Solarpunk foreshadows and aims to anticipate environmental catastrophe by skipping to solar. As Solarpunk manifesto-writer Adam Flynn writes, if “steampunk is ‘here’s yesterday’s future that we wish we had,’” and “cyberpunk was ‘here is this future that we see coming and we don’t like it,’” then “Solarpunk might be ‘here’s a future that we can want and we might actually be able to get.’”17

So who is “we”?

Solar Pasts

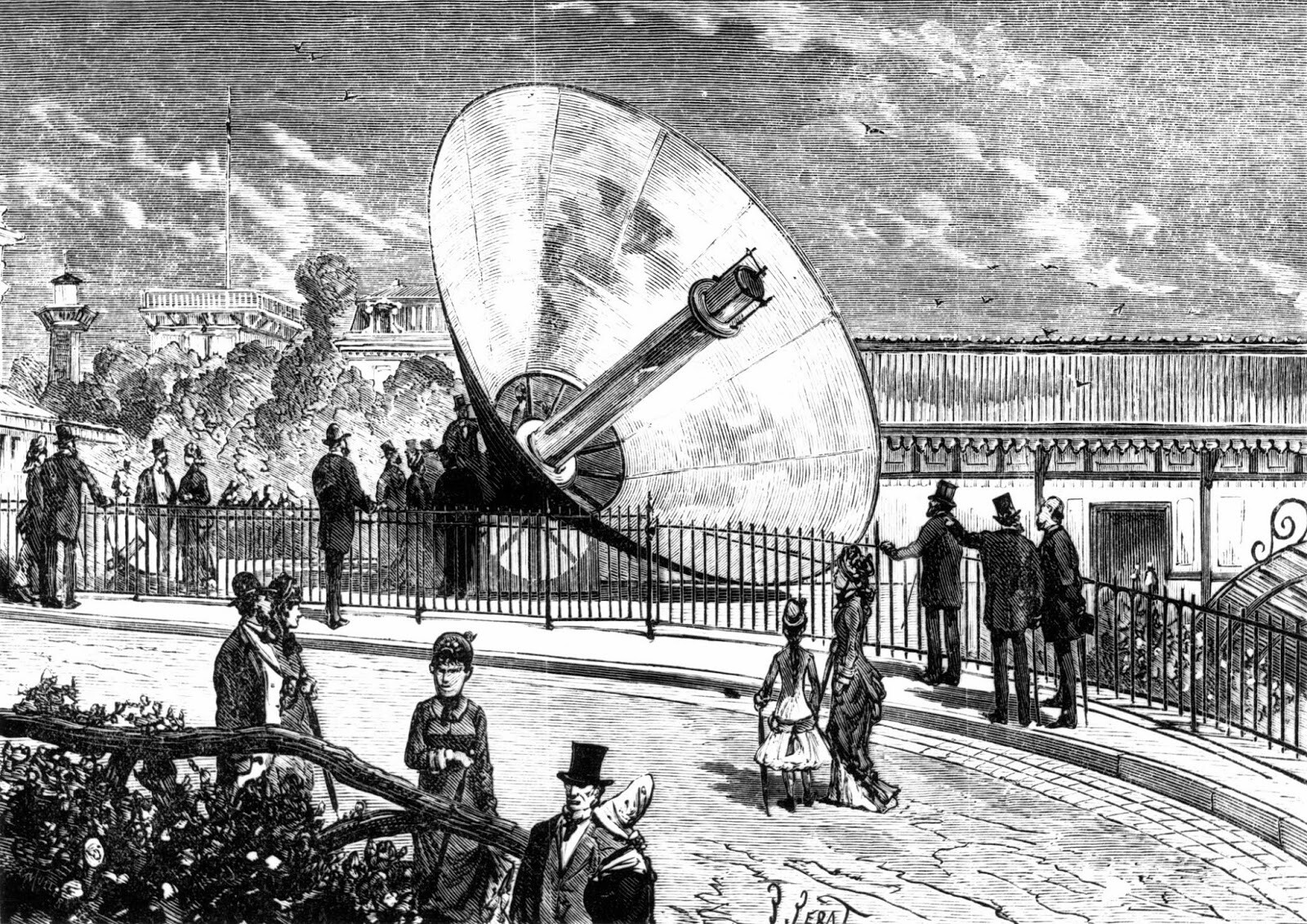

Solarpunk has a shadow history. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, innovations in solar architecture saw a major boom. Spurred by the “Little Ice Age” spanning from 1550 to 1850—a geological oddity in which Europe went through an extremely cold period—alternate heating methods led to the proliferation of glass-cased structures and the “Age of the Greenhouse” in eighteenth-century Western Europe.18 The ability to cultivate produce year-round was especially desirable given the new imported colonial fruits Europeans had developed a taste for.

By the mid-nineteenth century, as the middle class expanded, the typology of the greenhouse led to the conservatory, a solar-heated plant-room attached to well-to-do homes. As opposed to the practical, agricultural function of the greenhouse, conservatories presented botanical wonders as aesthetic objects and proof of accumulated wealth. “By the late 1800s the country gentry had become so enamored of attached conservatories that they became an important architectural feature” of late Victorian construction.19 A century later, however, coal power became more widespread, and many could afford to skip the actual solar engineering required to heat conservatories naturally, so instead artificially heated them by burning coal. By the time the Art Nouveau era began, the greenhouse had already receded in function, but remained as nature-inspired ornamentation: a decorative imitation of sustainable architecture. Such indoor botany also became gendered as a sanctioned hobby for house-bound women to occupy themselves with.20

Solar greenhouses were accompanied by other solar-tech advancements. One French Mathematician, Augustin Mouchot, invented a solar-powered steam engine, constructing the first functional prototype in the 1860s.21 It was applauded as a marvel, but the French sun wasn’t strong enough to reliably power the machine, and so it was sent to be implemented in the sunnier colonies. Mouchot traveled to Algiers to propose how solar power could be made an engine of expansion (with moderate success; his solar-powered ovens and wells were more popular). Similar stories were repeated in British and German colonies over the following decades, most dead-ending with the start of the First World War.

Technological innovation in no way guarantees a certain political implementation. Mouchot’s solar-engine utopia was a whole continent’s dystopia. And the global technology he was fixated on exporting was not particularly relevant or necessary to its “local” implementation. If Mouchot had only looked around when he arrived in Algiers, he might have noticed an advanced passive thermal regulation system already employed in traditional Algerian architecture.22

Dislocation

I see utopias as intensely practical, actually as the practical taken to extremes.

—McKenzie Wark23

If Art Nouveau references become an aesthetic shorthand for a utopian future, they’ll become another consumable trope for the wealthy to cling to. Luckily, “Consistent aesthetics don’t quite normalize across the imaginary,” says artist, theorist, and Solarpunk Jay Springett. By this he implies that Solarpunk will not and cannot mean one thing, no matter how meme-ified it becomes; it is forever open for adoption and appropriation. He emphasizes Solarpunk’s wide-ranging influences far beyond the Art Nouveau often readily associated with it: Saudi architect Sami Angawi’s updates on traditional methods of climate control in Middle Eastern architecture; permaculturing traditions around the world; Singaporean high-rises with living facades. Importantly, the first compendium of self-described Solarpunk fiction has come from Brazil.24 This is not enough in itself—there is always the potential for the old patronizing “learning from” attitude that Western architects are known for—and “Solarpunk should be careful not to idealize either the gothic high tech or the favela chic,” as speculative fiction writer Andrew Dana Hudson rightly cautions.25 But these manifestations of Solarpunk ethos hold political promise far more than tired Eurocentric idealisms.

Genre titles are a double-edged sword. They allow a body of work with an identifiable politics to emerge, but they also risk de-fanging the politics of the individual works when they are subsumed into the mass. In fact, Gibson says that the naming of subgenres like Cyberpunk was partially what paved the way for science fiction’s depoliticization. “A snappy label and a manifesto would have been two of the very last things on my own career want list. That label enabled mainstream science fiction to safely assimilate our dissident influence, such as it was. Cyberpunk could then be embraced and given prizes and patted on the head, and genre science fiction could continue unchanged.”26 Further, Cyberpunk could then be relegated to a bygone fad. In regards to Solarpunk: it’s a laudable goal to make greentech cool, but once it becomes cool, uncool is always waiting just around the bend.

Online, coolness can mutate. Solarpunk lives in the very cyberspace (maybe now post-cyberspace) that Cyberpunk emerged alongside. The internet may be increasingly sterile and homogenized, but there are still cracks where unexpected greenery grows. In that regard it’s worth noting that aesthetics evolve in tandem with the platforms they choose, which is to say that Pinterest might shoehorn Solarpunk visions into a different mold than tumblr or reddit, not to mention secret Slack channels or private Google groups (I assume these exist). The trick for the self-defined stewards is finding a way to gather and harness discourse without policing, claiming, or normalizing it. This is vital because, as opposed to Solarpunk’s still-non-normalized imaginary, “what is normalized,” says Springett, “are the shit corporate images which are the future aesthetic of global capitalism. Green Cities of new concrete and glass with no people in them.” And these the world certainly needs alternatives to. In the end, defending the possibility of non-apocalypse is hard and necessary work.

This is especially true given that contemporary capital doesn’t understand ironic proposition very well. For instance, Daisy Ginsberg, a designer who makes speculative projects sometimes called design fictions, has spoken about how one of her provocative projects, E.Chromi, meant to highlight both the potential benefits and hazards of personalized biotechnology, was apparently taken seriously as a business opportunity by hungry investors who came across it.27 The critique was lost on the section of the audience with the means to actualize it. If critique is inevitably bound to be taken as proposal at some level, there is an argument to be made that coming up with ideas you think are positive is simply the more ethical choice. That is, if Capitalist Realism reigns, you might as well represent ways to better the Real.28

And yet, should fiction really be burdened with practical responsibility? Or isn’t freedom from responsibility—existing as a means to its own end, rather than outside ends—exactly where its political potential lies? Isn’t fiction conveying a mission or plan exactly what leads to Ayn Randian bad art? Didn’t Hannah Arendt say that aesthetic production in service of idealism is what constitutes totalitarianism?

Certainly fiction-as-ideological vessel carries dangers. And earnest proposals, even without a strong ideological bent, are probably always somewhat at risk of functional exploitation; they may be reduced to a lowest common denominator and turned into dogma, nuance erased. And yet there is a fundamental difference between proposition and persuasion. This could also be framed as the difference between fiction that presents itself as a possible option versus the only solution. One allows the existence of multiple, coexistent realities; the other insists on a single best reality, which of course tends to be the “best” reality for the person proposing it. Maybe certain kinds of authorship are the problem with fiction-as-plan, not necessarily the fact of the plan itself.

Author Omar El Akkad said in a recent interview: “I’m not as interested in the question of whether the ideas at the root of my fiction could happen, so much as I am with the fact that, for many people in this world, they already have. I think of what I write less as dystopian and more as dislocative.”29 Solarpunk understood as “dislocative” fiction might be able to explicitly uncouple sustainable technological advancement from the purview of Western history entirely. This would not be, as Flynn rightly emphasizes in his manifesto, by proposing technological leaps into the future, nor by taking wistful glances at the past, but by looking laterally at what’s already in the world, or what has been historically overlooked. As Jared Sexton defines it, “Speculative: not only about possible futures, but also possible pasts and presents.”30

Dystopia is depoliticized when it is left as a stand-in for critique, able to be coopted toward any ideological aim. Dystopia “appeals to both the left and the right, because, in the end, it requires so little by way of literary, political, or moral imagination, asking only that you enjoy the company of people whose fear of the future aligns comfortably with your own.”31 Chelsea Manning recently gave a talk where an audience member asked: “What’s changed since you got out of prison?” She responded: “It’s a dystopian novel, but it’s a boring dystopian novel written by white men.” In other words, just as important as the affective slant of the story is the question of who writes it.

Like optimism and pessimism, utopia and dystopia are not really mutually exclusive.32 They are eternally coexistent as two sides of the same coin, always threatening to flip. I’m thinking, for instance, of a book of dislocative fiction by Octavia Butler, The Parable of the Sower, which tells the story of a new spiritual utopia arising from a destroyed continent. In the book’s sequel, that same hopeful community warps under the strain of fanaticism, flipping again; hope becomes cemented into dogma, which becomes destruction, which becomes (ostensibly) hope again. In order to propose utopia, she must also propose what comes after, or between.

That’s why, if Solarpunks’ goal is to close the plausibility gap, positivity for its own sake isn’t necessarily the point. Being constructive need not mean being starry-eyed. The site, the story, the style—these are not incidental to science fiction, even the hardest of the hard-tech kind. Pleasant green architecture means nothing if it becomes an extension of colonialist fantasy via the narratives of the same heroes that much Steam and Cyber abound with. To prevent earnestness from devolving into twee, the stories themselves need to be dislocated along with the imagery. Dislocation, rather than utopianism, is what will keep Solarpunk from running off as a libertarian seasteading vision, accelerationist implosion, or even just a store in the mall—and maybe even reclaim, if there such a thing, punk.

William Gibson interviewed by Abraham Riesman, “William Gibson Has a Theory About Our Cultural Obsession With Dystopias,” Vulture, August 1, 2017, ➝.

Belinda Goldsmith, “William Gibson says reality has become sci-fi,” Reuters, August 7, 2007, ➝. See also: Brady Gerber, “Dystopia for Sale,” Literary Hub, February 8, 2018, ➝. “Whatever your biggest concern—political polarization, climate change, the oppression of people of color and women, the unchecked evolution of technology—there’s a nightmarish fictionalized future already waiting for you. And if you want to be really informed, you can surround yourself with every potential bleak outcome. Everyone is allowed their own dystopia; they’re as easy to personalize as an iTunes playlist.”

Ben Valentine, “Solarpunk wants to save the world,” Hopes&Fears, August 28, 2015, ➝.

For dragons, see: Claudie Arseneault, Wings of Renewal (2017), ➝.

This diversity is endemic to the tumblrverse, but of course subcultures have always had factions (steampunk had its “tribes” too). See: “Steampunk Tribes,” Steampunk Scholar, March 5, 2017, ➝.

Claire L. Evans, “Does Future Fact Depend on Present Fiction?” uncube, March 11, 2014, ➝.

Project Hieroglyph recently released a book entitled Stories & Visions for a Better Future, ➝. It’s important to note that many authors mentioned in this essay do not claim the genre title of Solarpunk—any more than William Gibson waved the Cyberpunk flag, which he did not. Genre titles are often retroactively bestowed upon production that had no intention of being genre fiction of that sort. Over time, as a set of tropes emerge and coalesce, other production may pick up and carry the mantle, explicitly aiming to write or make within the genre ceonventions that have developed.

Neal Stephenson, “Innovation Starvation,” World Policy Journal (2011) 28(3), ➝.

See also: David Graeber, “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit,” The Baffler, March 2012, ➝.

Miss Olivia Louise, “Here’s a thing I’ve had around in my head for a while!,” Land of Masks and Jewels, 2015, ➝.

“Steampunk, which has been both upheld as a ideological movement and downplayed as an apolitical fashion trend, is only as politically substantial as people make it to be.” “Politics in Steampunk–A Sampling (aka “Why it Matters”),” Beyond Victoriana, April 6, 2013, ➝.

That is, although “steampunk enthusiasts like the grandeur of the British Empire,” they are not necessarily “willing to accept the racism and colonialism upon which it was built.” From: Mike Dieter Perschon, The Steampunk Aesthetic: Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture, Doctor of Philosophy and Comparative Literature, Fall 2012, Edmonton, Alberta.

V. Vale, phone interview, April 2017.

Perschon, The Steampunk Aesthetic.

Margaret Killjoy, “Steampunk Will Never Be Afraid Of Politics,” Tor, October 3, 2011. ➝.

Mary Woodbury, “Interview with Adam Flynn on Solarpunk,” Eco-fiction, July 2, 2014, ➝.

Ken Butti and John Perlin, A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1980). “Time after time, scarcities of fuel have stimulated the search for energy alternatives—spurring advances in solar architecture and technology. But when people discovered abundant new sources of fuel, solar energy became ‘uneconomical’ and dropped from sight.” Thank you to Jay Springett for pointing me toward this book.

Ibid.

See Nicholas Korody, “Mere Decorating,” e-flux Architecture, November 20, 2017, ➝.

Mouchot’s engine was powered by a water-filled glass container heated by the sun until it boiled. See: Butti and Perlin, A Golden Thread.

See: Fezzioui Naïma et al., “The Traditional House with Horizontal Opening: A Trend towards Zero-energy House in the Hot, Dry Climates,” Energy Procedia, Vol. 96, September 2016, ➝; Maatouk Khoukhi and Naïma Fezzioui, “Thermal comfort design of traditional houses in hot dry region of Algeria,” International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering, December 2012, 3:5, ➝.

McKenzie Wark, Anthropocene Lecture Series, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, May 18, 2017, ➝.

Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro, ed., Solarpunk: Histórias Ecológicas e Fantásticas em um Mundo Sustenavel (São Paulo: Editora Draco, 2012).

Andrew Dana Hudson, “On the Political Dimensions of Solarpunk,” Medium, October 14, 2015, ➝.

William Gibson Interviewed by David Wallace-Wells, The Paris Review, Summer 2011, ➝.

For more on E.Chromi, see Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and James King, E. chromi, 2009, ➝.

Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Zero Books, 2009).

Jason Kehe, “Sci-fi, Dystopia, and Hope in the Age of Trump: A Fiction Roundtable,” Wired, July 4, 2017, ➝.

Jared Sexton Interviewed by Daniel Barber, “On Black Negativity,” Society and Space, September 18, 2017, ➝.

Jill Lepore, “A Golden Age for Utopian Fiction,” New Yorker, May 29, 2017. “Anyone can do a dystopia these days just by making a collage of newspaper headlines. But utopias are hard, and important, because we need to imagine what it might be like if we did things well enough to say to our kids, we did our best… There are a lot of problems in writing utopias, but they can be opportunities. The political attacks {against utopian fiction} are interesting to parse. ‘Utopia would be boring because there would be no conflicts, history would stop, there would be no great art, no drama, no magnificence.’ This is always said by white people with a full belly. My feeling is that if they were hungry and sick and living in a cardboard shack they would be more willing to give utopia a try.” Terry Bisson, “Galileo’s Dream: A Q&A with Kim Stanley Robinson,” Shareable, November 4, 2009, ➝.

There is a lot to be gained here from the scholarship on the conjoined concepts of Afro-pessimism and black optimism. In this context Fred Moten describes “the infinitesimal difference between pessimism and optimism”: a difference arrived at not through opposition but something more like double-negation. Moten, “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh), The South Atlantic Quarterly 112:4, Fall 2013.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Category

Subject

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)