We’ll build houses like we used to, without roofs and without walls

—Vincenzo Agnetti1

After World War II, the view of Milan from Monte Stella—the artificial hill made out of rubble from the allied bombing designed by and dedicated to the wife of Piero Bottoni—was quite sad. These were the years of the ricostruzione, the material and metaphorical reconstruction of Italy after fascism; the opportunity to hurry Italy into the future, into industrialization, into the modernity that the Americans dropped along with the bombs. Meanwhile in Brianza, the territory just outside of Milan where Saint Augustine experienced his conversion, factories, artisanal workshops, and productions lines were slowly starting again, getting ready for, and excited by the promises of the Marshall Plan. A sense of euphoria came from the emptiness of loss, the erasure of a sedimented past. The harsh tabula rasa of Italian post war cities arguably spun a psychological urge to reconstruct, triggering that essential human ability of imagining, projecting, and making habitable. This condition would shape the country’s cultural and economic preoccupations and developments during the following decades. Within this unique scenario, creativity became something that transcended traditional disciplinary boundaries and produced alliances.

The bombing that cleared vast areas of Milan also hit a young artist’s studio, that of Lucio Fontana, who was then in his native Argentina, having returned to escape the war. It was during this time that he published his “Manifesto Blanco,” in which he foreshadows the generational interest into techniques of inhabitation and an interest in “space,” which would characterize Italian and European creative production for decades to come. Fontana’s manifesto presents art as a progressive amplification of the representation of space, and calls for the integration of color, sound, movement, time, and space into a “psycho-physical unity,” a sort of proto cyber-space. A year later, after returning to Milan, Fontana published the “First Spatialist Manifesto,” and in 1948, his first solo exhibition opened at Galleria del Naviglio with an installation called Ambiente spaziale a luce Nera: a black room with neon light emanating from an amoeboid structure in the middle of the space. Fontana’s room draws from and builds upon the Futurist concept of “entering the work,” and should be read against the background of Italy’s reconstruction and the urgency with which artists and architects would concentrate on the notion of space as a three-dimensional substratum that must be “furnished” to become habitable.

If Fontana’s manifesto was prophetic in its call for a unification of the arts, the actual historical development of what would today be called “cross-disciplinary collaboration” happened across parallel timelines and geographies. Beyond stylistic or aesthetic contingencies, the cosmos of creative practitioners that collectively advanced this project in Italy can tentatively be traced back to 1928 and the founding of Domus, a magazine for art, architecture and design by Giovanni Ponti. With the help of his daughter Lisa’s connections, Ponti, himself both an architect and painter, used Domus to animate a national and international debate by publishing the work of ever younger voices. It was through the magazine that Ponti began long and important collaborations with some of the most defining artists and designers of post-war Italy, namely Fontana, Nanda Vigo, and Ettore Sottsass Jr. Ponti’s epistle shows the extent and generosity of these collaborations, facilitated not only by his role as editor at Domus, but also as creative director of several institutions and industrial manufacturers.

Gio Ponti and Nanda Vigo, Casa Sotto la Foglia, Malo, 1965–68. Photo: Casali/Domus.

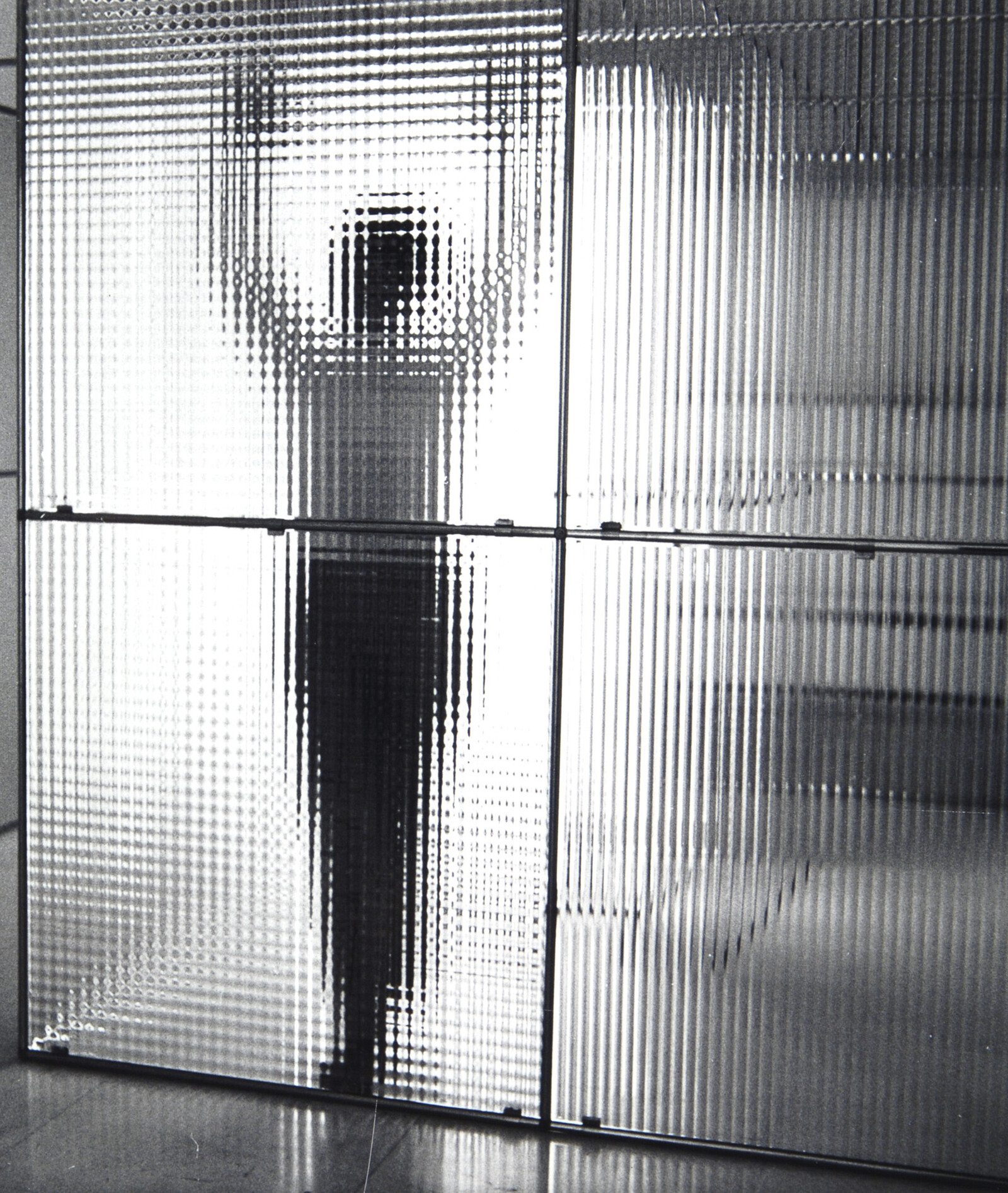

Nanda Vigo with Lucio Fontana, Labyrinth, detail, Gallery La Polena, Genova, 1968. Photo: Marco Caselli.

Nanda Vigo and Vincenzo Agnetti, Abitazione Privata su un teorema di Vincenzo Agnetti, 1972. Photo: Marco Caselli.

Lucio Fontana in collaboration with Nanda Vigo, Utopie, XIII Triennale di Milano, 1964. Photo: Salvatore Licitra.

Gio Ponti and Nanda Vigo, Casa Sotto la Foglia, Malo, 1965–68. Photo: Casali/Domus.

Nanda Vigo originally studied at the Polytechnic School of Lausanne and with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West. After fleeing Wright’s studio and his supposedly “utopian” Usonian school, which she found very unsatisfactory, Vigo started her practice as an architect in San Francisco and then in Milan. In 1959, while still in her twenties, Vigo showed up, unannounced, at Fontana’s studio and asked if he needed an assistant. It was in this casual encounter that one of the most defining cross-disciplinary collaborations of post-war Italy began. Vigo and Fontana would go on to develop many projects together, both for interiors, with whom they often collaborated with Enrico Castellani and which they called “unità abitazionali” (“habitational units”), and environments. Her interior projects, such as Zero House (1959-62), Yellow House (1970), Blue House (1967-71), and Black House (1970), are driven by Vigo’s spatial, three-dimensional canvas in which the two-dimensional work of spatialist artists, such as Lucio Fontana and Enrico Castellani, would find a fitting universe to inhabit.2

It was through Fontana that Vigo would meet Gio Ponti. Even if much older than Vigo, Ponti had deep admiration and respect for the young designer and artist. Ponti began commissioning Vigo for a series of smaller projects such as cronotopi, tridimensional structures that entangled, captured, and re-organized light for the Ideal Standard showroom (1965), and a furry tunnel for the trade show Eurodomus (1968). Their largest and most important collaboration was Casa Sotto la Foglia (1965–68) in Malo, a small town near Vicenza. The project began as a site-less design resulting from Ponti’s search for alternatives to the constructivist and Corbusian domestic design ethos. The design was originally published in Domus and offered as a gift to whoever wanted to build it. Vigo brought in an entrepreneur from the thriving Veneto Region who had started collecting her artworks, and whom she was advising in building a collection, to sponsor its construction. In exchange, Ponti let Vigo have free reign over the interiors, where she collaborated on architectural elements with many artists, including Fontana, Castellani, and Luciano Fabro. Her design for a monochrome environment (a spazio bianco a la Fontana and Zero Group) with ceramic tiles, built around a central bed nicknamed by Ponti the “Nativity Room,” would become one of the most significant (and overlooked) interior projects of post-war Europe.

One year after completing Abitazione Privata su un teorema di Vincenzo Agnetti (1972), a house in collaboration with artist Vincenzo Agnetti, Vigo was asked to design the atrium of Palazzo dell’Arte for the 1973 Milan Triennale. In previous editions, this space had been conceived as a monumentally empty space, even when designed by Vittorio Gregotti and Umberto Eco for the 1968 edition that was infamously shut down by student and worker protests. Vigo twisted the spatial program and transformed it into an environment for performance that she named Spazio Azioni (“Space for Actions”), for which she curated the events program with art critic Pierre Restany. The main gesture was to turn the monumental stair designed by the building’s architect, Giovanni Muzio, into a space of institutional parades and rituals; a white, impromptu free theater floating on a black horizon.

Ettore Sottsass Jr., Elea 9002, Olivetti, 1958.

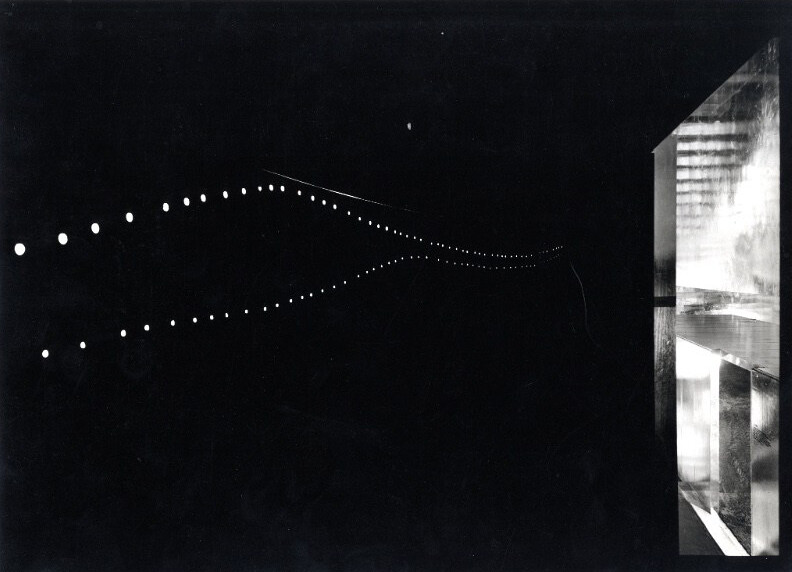

Ettore Sottsass Jr., Virtual Architecture, 1973.

Ettore Sottsass Jr., Metaphors, 1972–1978.

Ettore Sottsass Jr., Elea 9002, Olivetti, 1958.

Parallel to his productive relationship with Vigo, Ponti would begin to develop close relations with Ettore Sottsass. Their collaboration would span many decades and follow the zelig-like contortions of Sottsass’s creative practice. Sottsass traversed post-war Italian design culture with a mixture of international influence, response, and disruption at every turn. Unlike Vigo, Sottsass’s production is more heterogeneous and fluid, as it transitioned from embracing design as a critical practice with, for instance, Virtual Architecture (1973), to moments of complete passion for objects qua commodities, such as with his work for Olivetti and as a part of the Memphis collective in the 1980s. From his 1950s wall compositions in which furniture, space, and painting are conflated to reconfigure domestic space with a mise-en-scène of affective and plastic connotations to Metaphors (1972–79), a photographic exploration of minimal dwelling in various deserts that rejected the industrial commoditization of the domestic, Sottsass’s work anticipated the duplicitous movement both towards and away from pop that characterizes artistic discourse in Italy throughout the post-war period.

Manufacturing the Future

A stance on modern industry’s re-semanticization of domesticity, within which design was attributed salvific political powers and helped cultivate the paradoxical idea of an ethical capitalism—that through design industry could make positive change—would constitute the main divisions between artists and designers operating in post-war Italy. Olivetti’s successful experiments in industrial design, for example, gave way to many designer-led companies which sprouted throughout Italy, including Tecno (1953) from the Borsani Brothers, Azucena (1947) by Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Flos (1962) by Dino Gavina, and others like Alessi (which while founded in 1921, only started working with designers in the early 1970s), Kartell (1949), and Gufram (1966). Indeed, Italy’s so-called “economic boom” of the 1960s and the burgeoning consumerist culture was fueled by industrial design.

Installation view of the exhibition “Gilardi, Piacentino, Pistoletto. Arte Abitabile,” Sperone Gallery, Turin, 1966. Photo: Gian Enzo Sperone.

If both Vigo and Sottsass found fertile ground and support in Italy’s burgeoning industrial capitalism, the work of Arte Povera represents an alternative position. Just a few months after Gufram was founded, the exhibition “Habitable Art” opened at the Sperone Gallery in Turin featuring works by three young artists—Piero Gilardi, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Gianni Piacentino—who each in different ways addressed domestic space as a new site for negotiating the political role of creative labor in society. Piero Gilardi presented his “nature carpets,” foam rubber manufactured by Gufram painted with grass, rocks, dirt, and the like in extreme and uncanny detail as a synthesis of industrial production and artistic craft.

Just as the artists of Arte Povera were skeptical of the capitalist logics behind contemporary design and architecture, many architects at the time were founding groups that, like Sottsass, pursued the idea of “critical design.” Archizoom Associati and Superstudio were both founded in the same year as the “Habitable Art” exhibition, and in the beginning, had strong connections with its proto-poverist experiments. Even though Pistoletto’s semisfere riflettenti would have fit perfectly in an Archizoom environment, the connection was not so much aesthetic but political, as both engaged with the workerist theories shaping Italian counter-culture at the time.3 That said, it is unclear whether either artisti poveri or architetti radicali managed to surpass the question of style and transcend into the political agency Gramsci wished through culture and aesthetics,4 or if they rather remained within what Roland Barthes would call “Italianicity,” or the supposed ability “to present images which, however ‘ordinary,’ are handled with uncanny ‘style.’”5

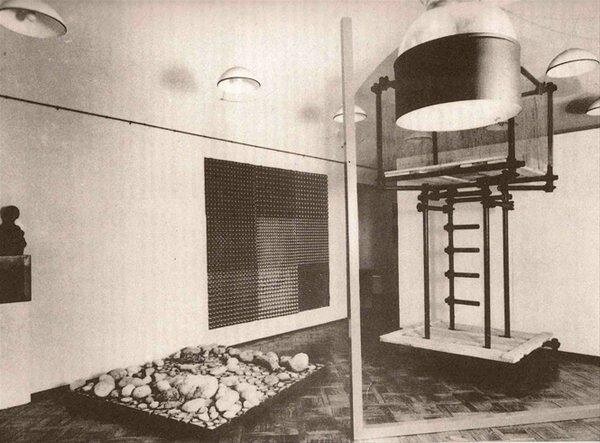

Ettorre Sottsass Jr., Containers, double module stove/oven and sink/dishwasher for the exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” at the Museum of Modern Art New York, 1972. Photo: MAK/Georg Mayer.

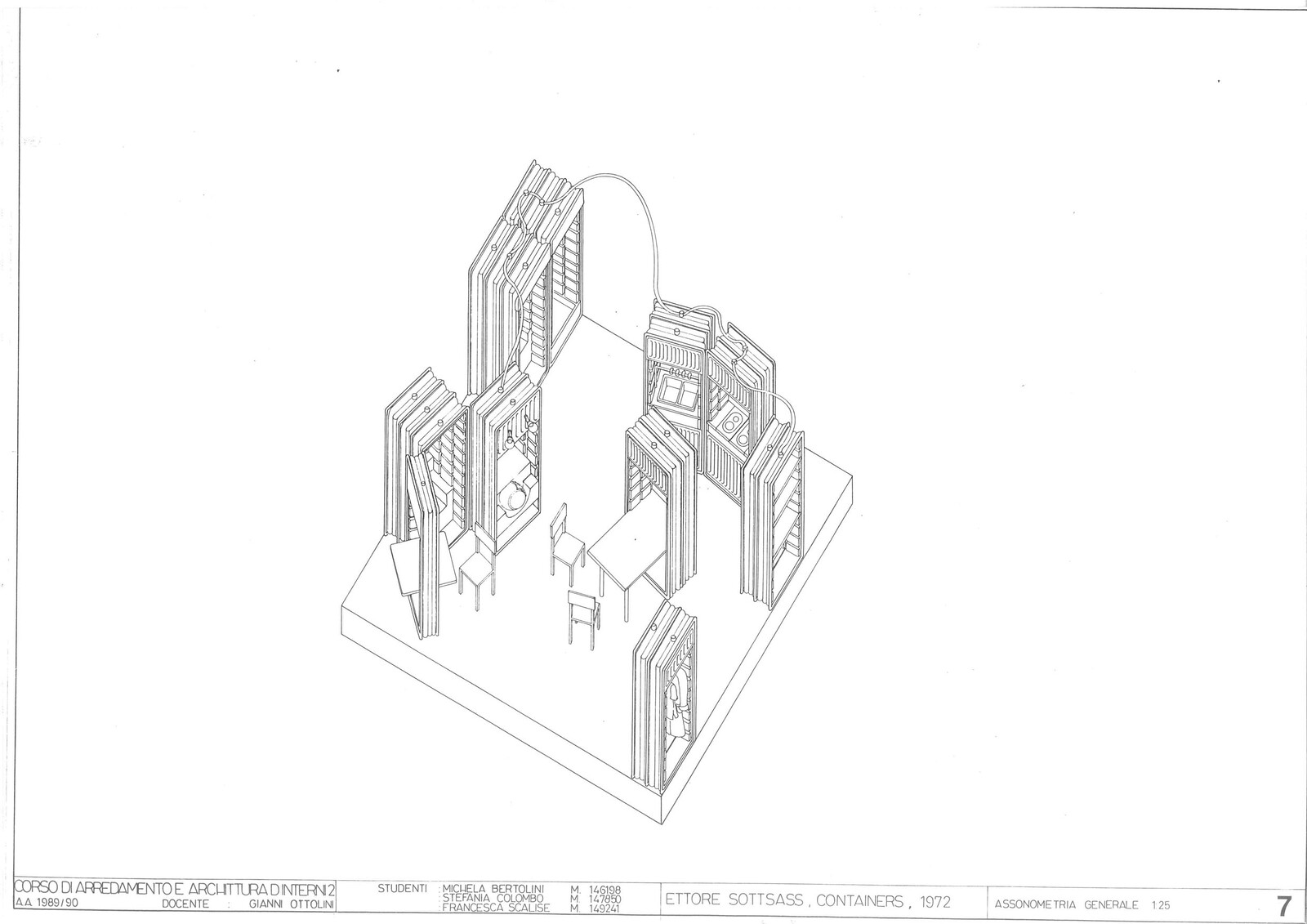

Ettorre Sottsass Jr., Containers, axonometric drawing for the exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” at the Museum of Modern Art New York, 1972. Source: Atlas of Interiors.

Ettorre Sottsass Jr., Containers, single module for the exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” at the Museum of Modern Art New York, 1972. Photo: MAK/Georg Mayer.

Ettorre Sottsass Jr., Containers, double module stove/oven and sink/dishwasher for the exhibition “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape” at the Museum of Modern Art New York, 1972. Photo: MAK/Georg Mayer.

The paradox of design as the practice of making the world habitable—simultaneously bound to the political and economic status quo while imagining alternative forms of life—was canonized by the 1972 MoMA exhibition “Italy: A New Domestic Landscape.” Perhaps the most emblematic project in that exhibition was Sottsass’s Containers (1972), a series of movable pods that contained domestic apparatuses such as a bed, sink, table, shelving, closet, and juke-box, made for those who “have the conscience of the existential disaster of our time.”6 Dedicating the project to Vigo, who “explained everything to [him],” Sottsass laconically called these pods, which were manufactured by Kartell, “living containers.” Maybe this was a way for Sottsass to recognize the dead end of design as life-management and question its possibility as a critical, conceptual practice.

One could argue that Sottsass’s Containers project polemically tried to kill the idea of design that developed in post-war Italy—as something more than pure form-giving and problem-solving—precisely at the point when it received its highest recognition. Containers shows that all basic needs for human inhabitation can be resolved in a satisfying and economical manner with industrially produced units. With this, design reaches a point of saturation, after which it becomes a purely aesthetic practice of form-giving. And indeed, after the MoMA exhibition, Sottsass’s own practice became increasingly concerned with pure creative expression and myth-making.

If the ruins of WWII created the conditions to devise new techniques of inhabitation, then the re-coding of reality which used to happened only in our brains is now is operated—with ostensibly greater computational power—by other forms of disembodied intelligence, there is a need to learn how to inhabit new and augmented realities. We might therefore be due for a reevaluation of how we understand design. After the invention of GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), a first step towards machine imagination, there is, perhaps, an urgency to reclaim design as the fundamental neurological capacity of mobilizing creative, analytical, and critical capacities towards anticipating, abstracting, remaking, and projecting the world.

“Costruiremo le case come una volta senza tetti e senza mura,” translation by the author, quoted from Vincenzo Agnetti, OBSOLETO (Milan: Vanni Scheiwiller, 1968).

The Zero House was named after the pan-European Zero Group of which Vigo was a peripheral, yet influential member, having organized the first Zero exhibition at Fontana’s studio with twenty-eight artists from all around continental Europe. See ➝.

See Nicholas Cullinan, “From Vietnam to Fiat-nam: The Politics of Arte Povera,” October 124 (Spring 2008): 8–30; Pier Vittorio Aureli Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture Within and Against Capitalism (New York: Buell Center / FORuM Project and Princeton Architectural Press, 2008).

Antonio Gramsci, Quaderni del carcere, ed. Valentino Gerratana (Turin: Einaudi, 1975).

“Rhetoric of the Image” in Roland Barthes, Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978).

Emilio Ambasz ed., Italy: The New Domestic Landscape (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972): 160–169.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)