In 1930, the French colonial regime celebrated the hundredth anniversary of France’s colonization of Algeria, known as Le Centenaire de l’Algérie française (Centenary of French Algeria). These colonial celebrations were held in Algiers and in other cities in Algeria under French rule (1830–1962) during the first six months of 1930, and included a number of commemorative, artistic, theatrical, and sport festivals and events. According to Gustave Mercier, French lawyer and general curator of the programs of the Centenary, the aim of these colonial festivities was to “demonstrate that it exists, next to millenary France, at twenty hours from Marseilles, on the other side of the Mediterranean that gave birth to Hellenism and Latinity, another France, barely hundred-year-old, already strong, full of life and future, uniting in its happy formula Latin races and indigenous races, in order to make them all French races.”1 This colonial doctrine was called assimilation.

The French colonial authorities used the term “indigène” (indigenous) to designate the Algerian Arab and Berber populations living in Algeria long before France’s colonialization.2 The Jewish community also living in Algeria had been incorporated into the French population in 1870 when they were granted French citizenship under the Crémieux Decree.3 The French referred to the Algerian Arab and Berber populations as either indigènes sujets français (Indigenous French Subjects), sujets français (French Subjects), or simply indigènes (Indigenous), all of which were not French citizens. In Algeria under French colonial rule, the Algerian Arab and Berber populations were considered citizens of neither Algeria nor France. The rights and duties of the so-called “indigenous” populations were dictated by the French colonial legislation known as the Code de l’indigénat (Code for the Indigenous). Designed to promote France’s colonial unhappy “formula” of assimilation and ensure Algerians to have unequal rights as French citizens, the Code was a set of discriminatory regulations that failed to accord any constitutional, political, or economic protection to the populations that were subjected to it.

The year 1930 coincided with the settlement of French architect Marcel Lathuillière in Algiers after coming second in the Foyer civique (Civic Foyer) design competition of 1927, launched by the municipality of colonized Algiers, to which he had submitted a design project along with the Algiers-born-and-based architect Albert Seiller. The two French architects became partners in 1928.4 In 1932 the Algiers Group of the Société des architectes modernes (SAM, or Society of Modern Architects—a French organization that had been created in 1922) was established. The Algiers Group’s active members included Lathuillière, Seiller, and the winner of the aforementioned Civic Foyer competition, Léon Claro.

The SAM requested all of its adherents “to build on the principles of modern aesthetics, excluding any pastiche and any reproduction of ancient styles, whenever they are not prevented by absolute necessity.”5 In the context of colonized Algiers, this “pastiche” referred to the neo-Moresque style that was encouraged by Charles-Celestin Auguste Jonnart and dominated French colonial architecture of the early twentieth century. Jonnart served as General Governor of Algeria in 1900, between 1903 and 1911, and then again from 1918 to 1919, and was partly inspired by the studies and opinions on the Arab kingdom of the Emperor of the French Second Empire, Napoleon III.6 In an article entitled “Il faut être de son temps” (“It Is Necessary to Be Contemporary”) published in Chantiers, an Algiers-based architectural magazine, Frantz Jourdain, President of the Paris SAM, criticized the outdated educational system of the Beaux-Arts that had “poisoned the youth” and lauded the Algiers SAM’s accomplishments: “my colleagues [in Algiers], in a few years, have done more in favor of modern evolution than the French architects [in Paris], who are too indecisive, divided, uncertain, confused, and torn in different directions.”7 If Algiers-based French architects succeeded in imposing nonregional architectures, or modern architecture deprived of “pastiche,” it was because the French colons in Algeria virulently criticized and condemned the stylistic choices of the General Government, arguing that neo-Moresque forms did not belong to them. Instead they mainly favored a style in Algiers that was intrinsically recognizable as “European.”8

Emmanuel de Thubert, General Delegate of the Paris SAM, stated that the group encompassed many diverse personalities, naming some of them after construction materials: the “Friend of Iron” (Frantz Jourdain), the “Master of Cement” (Auguste Perret), and the “Protagonist of Steel” (Henri Sauvage). He also stressed that one of the most beautiful branches of the SAM was the Algiers Group founded by Lathuillière and his friends, because it demonstrated that “on both sides of the Mediterranean reign the same spirits and beat the same heart, so that France is both in Algiers and in Paris.”9

Algiers hosted the first Exposition d’urbanisme et d’architecture moderne (Exhibition of City Planning and Modern Architecture) in February 1933, three years after the monumental centenary celebrations of the French colonization of Algeria. The exposition also came two years after the International Colonial Exhibition in the Bois de Vincennes in Paris in 1931, which displayed the immense resources of both the French colonial empire and other colonial powers. In terms of the preparations for the 1933 exhibition, Lathuillière was the deputy president of the organization committee, Seiller was the general curator, and Pierre-André Emery, a Swiss-born architect, early collaborator of Le Corbusier’s, and a vocal supporter of his plans for Algiers, was the general secretary. The exhibition was organized by the influential Association d’urbanisme Les Amis d’Alger (Association of Urbanism Algiers’ Friends), the Algiers SAM Group, and the Trade Union Association of Architects Graduated and Admitted by the Government.10

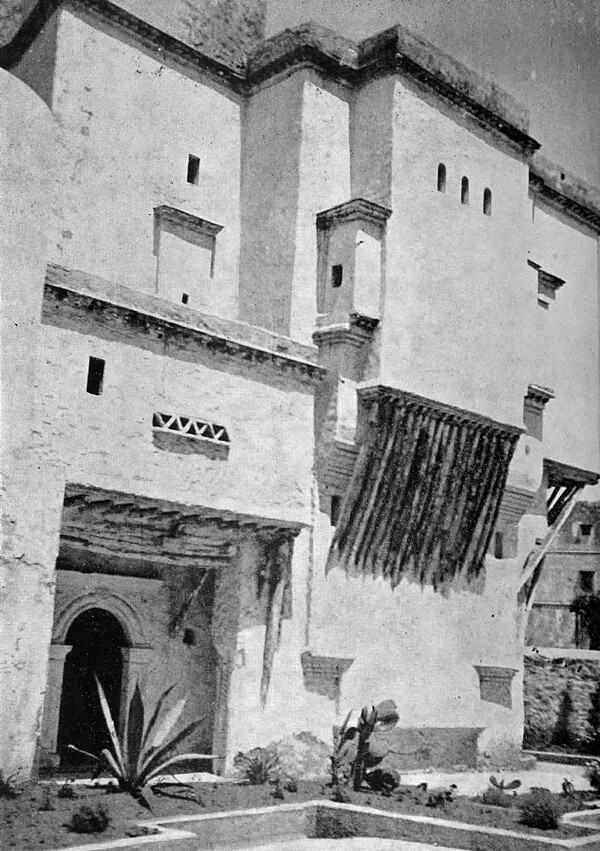

La maison indigène du centenaire (Indigenous House of the Centenary) designed by Léon Claro on the occasion of the celebrations of the Centenary of French Algeria, 1930.

Rudolphe Rey, who invited Le Corbusier to Algiers and was the president of the exhibition committee and the president of the Amis d’Alger, asserted in an article titled “Tous urbanistes!” (“All Town Planners!”) that “planners and architects in Algeria, closely united in the continuation of their generous effort, will not cease to guide public authorities in their great task of remodeling and developing our African cities.”11 In a special issue of Chantiers dedicated to the exhibition, the articles and the projects presented were divided into two parts: first, urbanism and the large-scale planning and development of cities in Algeria; and second, architecture and modern construction in Algeria.12 Lathuillière published an article with the title “L’architecture moderne et l’aménagement de l’habitation” (“Modern Architecture and the Configuration of Housing”), whereas Seiller reported his ideas in an article under the heading “L’hygiène dans l’habitation” (“Housing Hygiene”). Both contributions focused entirely on housing built for the French population in colonized Algeria.

The question of housing designed for the Algerian population was only dealt with directly in one article: “L’habitation indigène et les quartiers musulmans” (“Indigenous Housing and Muslim Neighborhoods”), written by French architect François Bienvenu, who was born and based in Algiers working for the French General Government. Bienvenu described the ongoing public debates on the types of housing in which Algerians—or, as they were called, the “indigenous” people—were expected to live. He described two opposing schools of thought, neither of which had been able to forge a commonly acceptable compromise. The debates centered around a rhetorical question: was it necessary to conceive and build dwellings that would satisfy the current lifestyle of the Algerian population, or would it instead be better to envisage the adaptation of Algerians’ modes of living to the French colonial lifestyle through European-type housing?13

Some French representatives believed that if Algerians were to inhabit European-style dwellings, new needs would be generated that would be incompatible with their salaries, thus representing a threat to colonial agriculture and industry. Others thought that if the Algerian population lived in European-style housing, it would stimulate new commercial transactions that would in turn be beneficial to the entire colony, and therefore to the European community.14 Both arguments were rooted in economic issues and were engraved in colonial practices. According to Bienvenu, who designed and built housing for Algerians in Algiers, “the problem of the resettlement of the indigenous population should be the priority, the key problem on which everything else depends: sanitation, circulation, development, and embellishment.”15

In April 1936, Lathuillière curated the second version of the Exhibition of Urbanism and Modern Architecture, this time called the “Exposition de la cité moderne: urbanisme, architecture, habitation” (“Exhibition of the Modern City: Urbanism, Architecture, Housing”) which took place in the uncompleted Civic Foyer in Algiers. The exhibition was comprised of four different sections: urbanism, architecture, housing, and construction techniques. Seiller curated the housing section, which displayed the interiors of dwellings, their layout, furniture, and decoration, and Emery was again the general secretary of the exhibition.16 A special issue of the French magazine L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui—which Lathuillière was the Algerian correspondent for between 1935 and 1948—was devoted to La France d’outre-mer (Overseas France) for the occasion. This time, the exhibition featured the habitat indigène (“indigenous” housing) in all of the French overseas colonies and protectorates, but Algeria in particular.

Positions on how to design housing for Algerians, or as the French called them “indigenous” housing, were again divided. The president of the HBM (Habitat à bon marché, or Low-cost Housing) Office of the Municipality of Algiers expressed his opinion in an article “L’habitat indigène en Algérie” (“Indigenous Dwellings in Algeria”), arguing that “indigenous dwellings must meet the requirements of customary mores, which demand the absolute privacy of the home.”17 He illustrated his text with the housing project designed by Bienvenu. Lathuillière, by contrast—who in the meantime had obtained authorization to build public works for the French General Government in Algeria—stressed in his article “Le problème de l’habitat indigène en Algérie” (“The Problem of Indigenous Housing in Algeria”) that “it would be an error to push respect for their [Algerian] customs to the point of trying to recall, by form and disposition, ancient buildings.”18 Lathuillière’s proposal was to group together the non-European populations who lived in Algeria—as he noted, the Arabs, Berbers, Turks, Mozabits, and others communities that had Islam as a common bond—and he presented a design for a housing complex intended for non-Europeans in Algiers. He also expressed the breadth of his design agenda, recommending that “new constructions will have to be careful about satisfying old customs, and should guide some habits in order to pave the way for a gradual assimilation to Europeans mores.”19 Unlike Bienvenu, Lathuillière conformed to Mercier’s aforementioned proclamation and French assimilationist doctrine, which dominated the French colonial design of housing units for the Algerian populations in Algeria in the 1950s and 1960s.20

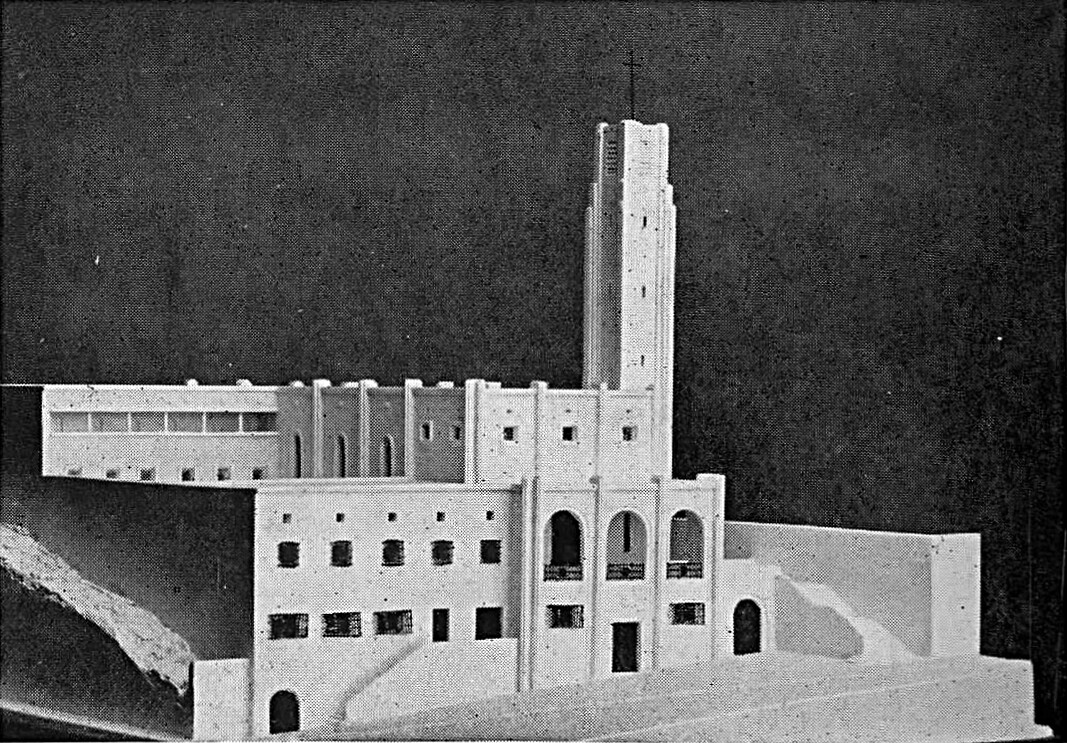

François Bienvenu, Cité Indigène de la Boucle, 1936.

Guérineau et Bastélica, Hotel de Ville de Djidjell, 1936.

Bonet et Carbonell, Cité des Dominicains, 1936.

François Bienvenu, Cité Indigène de la Boucle, 1936.

The 1936 Exposition also showcased the architecture of precolonial dwellings in the French colonial Empire in a section dubbed Habitation indigène (Indigenous Housing). In his article entitled “L’habitation indigène dans les colonies françaises” (“Indigenous Housing in French Colonies”), Marcel Persitz illustrated a number of exhibits from this section, covering French North Africa, French West and Equatorial Africa, French Madagascar, French Indochina, and French Oceania.21 Precolonial housing settlements in French North Africa (French departments of Algerian, French protectorates of Morocco and Tunisia) were divided into two categories: L’habitation rurale (rural dwellings) for both nomadic and settled populations, and La maison urbaine (the urban house), which consisted primarily of courtyard houses. The author expressed his admiration for the great variety of peoples who lived in this immense and diverse territory, and highlighted the extent to which both the human and natural environments were faithfully reflected in the meticulous proficiency of their habitations. The author also argued that traditional housing settlements—that is, pre-French colonial dwellings—were shaped to regional geographic and climatic conditions, embodied cultural values, and provided the setting for various social customs, including family privacy and the separation of activities according to gender.22

To this end, the colonial appellation “indigenous” housing referred not only to the dwellings designed and built by the French colonial authorities for the colonized populations during the colonial time, but also to precolonial regional domestic architecture built prior to French colonization. In other words, “indigenous” housing signified interchangeable times and spaces (precolonial and colonial) because the French colonial regime used the term “indigenous”—which was bound up with the juridical status of the Algerian populations ruled by Code de l’indigénat—to designate Algerians and nearly anything that was related to the Algerian colonized population.

With the abolition of the Code de l’indigénat in the aftermath of the Second World War, it was recognized that the term indigène, rooted as it was in racial differences, needed to be substituted. At this juncture, the French colonial authorities renamed the Algerian populations as Les français musulmans d’Algérie (French Muslims from Algeria), although they were still not given the benefits of full French citizenship. The racial designation “indigenous” was therefore replaced by that of religion “Muslim,” yet an appellation that still controversially discriminated Algerians from other communities who lived in Algeria. While for Algerians the criteria for being named was based on religious affiliation, for Frenchmen, Jews, and Europeans, they were based on juridical citizenship. The “non-Muslim” populations—which included Christians from France and other European countries, as well as Jews—were called neither French Christians nor French Jews; and for unknown reasons, Jews and Christians were perceived to be one cohesive group. The colonized Algerian population was thus the sole community to be officially defined in terms of its religious faith.

The change in terms, from indigènes sujets français to français musulmans d’Algérie, resulted in a change in housing taxonomy: what was named “habitation indigène” came to be renamed “habitat musulman” (Muslim housing).23 Despite the change in terms, the appellation remained a deeply colonial one, and design thinking continued to be based on assimilationist principles, which continued to spawn several studious debates among colonial administrators, politicians, and architects.

One such set of discussions took place during the French twelfth Congrès national d’habitation et d’urbanisme (National Congress of Housing and Town Planning) held in May 1952 in Algiers. The Congress was organized by two influential French institutions: the Union nationale des fédérations d’organismes d’HLM (UNFOHLM, or National Union of Federations of HLM Organizations) and the Confédération française pour l’habitation et l’urbanisme (CFHU, or French Confederation for Housing and City Planning). As an additional part of the Congress, a study trip devoted to the questions and problems of urban dwellings in Algiers was organized by the Fédération algérienne des organismes de HBM (Algeria-based Federation of Low-cost Housing Organizations).24 Eugène Claudius-Petit, French Minister of Reconstruction and Urbanism, and other representatives of various French housing agencies and legislative bodies attended the Congress. The presence of these European officials reinforced the idea that France and Algeria faced similar housing and planning issues, yet at the same time also underscoring the fact that Algeria was in reality profoundly different. One of these major dissimilarities consisted of the socio-cultural composition of Algeria’s inhabitants: that is, that Algeria was not only populated by French citizens (including Jews) and European communities (Italian, Spanish, Greek, Maltese, German, and Austrian, among others, who had the basic right to easily become French citizens), but also by Algerian populations (the so-called “Muslims”). To this end, the Congress involved an animated discussion about the housing-unit typologies in which the two communities should dwell: French and Europeans versus the Algerian populations. These deep discrepancies between Algeria and France were evident in the debate about a purported housing type for Algerians, from which two opposing policies emerged.25

One position was developed by the French participants from the Métropole, who advocated an emblematic colonial planned segregation and a “compartmentalized world,” as argued by Frantz Fanon,26 involving the design of three categories of housing settlements:

1) Low-cost and low-rise dwellings created for specific classes of the Algerian population—called the musulmans non évolués (“non-developed” Muslims) and musulmans peu évolués (“less-developed” or “underdeveloped” Muslims)—who had no choice but to live in shantytowns. This proposal was spatially and financially comparable with the cités d’urgence (emergency settlements) built in post-WWII France.27

2) Habitat à bon marché (HBMs) aimed at the European working-class populations and a small fraction of Algerians described as the “Muslim population that has already achieved a certain degree of development.”28

3) Dwellings for the European middle classes eligible for public funds to make private investments.

The second approach was promoted by Lathuillière, who by this point was an architectural adviser to the General French Government in Algeria, a member of the Council of the Order of Architects in Algeria, and the president of the North African Section (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia) of the Union of International Architects (UIA).29 This latter stance aspired to “a radical and assimilationist urban modernization,” a position that rejected community-based designs, single-family housing, and low-rise dwelling units, instead encouraging collective multi-family high-rise buildings in which the two communities, Algerians (called “Muslims”) and Europeans (including French people), would be required to learn to live together.30 Unlike Europeans, however, under this model Algerians had no alternative but to “assimilate” themselves to French colonial dictates and to adopt French models of domesticity. This assimilationist doctrine continued to prevail in most housing projects designed by the French authorities for the Algerian populations in the following decades.

According to Lathuillière, “a dwelling has a great influence on the behavior of a family. … Collective dwellings impose disciplines that shape the civilized man. This is where the role of the architect is clearly apparent: a role that goes far beyond the boundaries of art and technology and gains a greater social significance.”31 The French colonial regime was well acquainted with the disciplinary role of modern architects and architecture, and thereby, the majority of the members of this regime advocated for a design of dwellings for the Algerian population—called first “Indigenous” and then “Muslims”—that “assimilated” Algerians into French norms and forms: a self-assigned violent practice that is deeply colonial. In colonial conditions, as well as in neocolonial, endocolonial, and postcolonial conditions, the act and logic of naming and classifying certain populations, genders, programs, strategies, and built environments mirror the mechanisms of segregation, reflect the domination of some people over other people, and maintain supremacist methods of power and knowledge. These acts and logics have to be meticulously scrutinized in order to inscribe the rhizomatic roots of racist discourses and speeches, which are omnipresent today.

Cited in Nabila Oulebsir, Les usages du patrimoine: monuments, musées et politique coloniale en Algérie, 1830-1930 (Paris: Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2004), 261.

The French colonial term “indigène” is often translated into English as either “indigenous” or “native.” In the English-speaking context, it is interchangeably used today in expressions like “indigenous knowledge,” “indigenous populations,” “indigenous art,” and “indigenous architecture.”

The 1870 Crémieux decree was abolished from 1940 to 1942 under the Vichy regime.

Lathuillière graduated from the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he attended the Atelier Emmanuel Pontremoli, a neoclassicist architect and winner of the Prix de Rome; he was likewise in contact with the Atelier du Palais de Bois, directed by Auguste Perret. See, for example, Boussad Aïche, “Figures de l’architecture algéroise des années 1930: Paul Guion et Marcel Lathuillière,” in Architecture au Maghreb (XIXe-XXe siècles) (Tours: Presses Universitaires François-Rabelais, 2011).

Article 2 of the constitutive statues of the SAM, as cited by the General Delegate of SAM in Emmanuel de Thubert, “Architecture moderne,” Chantiers, no. 3 (March 1933): 291–93.

On the French neo-Moresque style in Algiers, see for example Nabila Oulebsir, “Les ambiguïtés du régionalisme: le style néomauresque,” in Alger: paysages urbain et architectures, 1800-2000 (Paris: Les Editions de l’imprimeur, 2003), 104–25.

Frantz Jourdain, “Il faut être de son temps,” Chantiers, no. 3 (March 1933): 290.

Ibid., Oulebsir (2003), 118.

Ibid., de Thubert, 292.

The Algiers-based magazines Travaux nord-africains and Chantiers dedicated special issues to the exhibition. See Travaux nord-africains no. 1136 of 18 February 1933 and Chantiers no. 3 of March 1933. The first part on urbanism in Chantiers included the famous projects by Tony Soccard, Maurice Rotival, and Le Corbusier for the Quartier de la Marine.

Rudolphe Rey, “Tous urbanistes!,” Chantiers, no. 3 (March 1933): 237.

François Bienvenu, “L’habitation indigène et les quartiers musulmans,” Chantiers, no. 3 (March 1933): 246.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. On Bienvenu, see for example Zeynep Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997), 130–43.

Exposition de la cité moderne : urbanisme, architecture, habitation, Alger du 28 mars au 19 avril 1936 (Alger: Comité d’Organisation, 1936), 8–9.

Pasquier-Bronde, “L’habitat indigène en Algérie,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 3 (March 1936): 20.

Marcel Lathuillière and Albert Seiller, “Le problème de l’habitat indigène en Algérie,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 3 (March 1936): 22.

Ibid.

Samia Henni, Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria (Zurich: gta Verlag), 205–232.

Marcel Persitz, “L’habitation indigène dans les colonies françaises,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 3 (March 1936): 13–19.

Ibid., 14.

This does not mean that the term “Muslim” was never used before 1945. On the contrary, Islam and Muslim customs had been a subject of study for the French administration and social scientists since the onset of French colonization. The term “Muslim” was also used to designate a specific category of urban planning, for instance in Georges Marçais, “L’urbanisme musulman.” Algérie (May 1936), 8–9. Other expressions were also used, such as maison moresque (Moresque house) or urbanisme nord-africain (North African Urbanism). Except in a few cases—for instance in René Lespes’ article “L’évolution des idées sur l’urbanisme algérois de 1830 à nous jours.” Chantiers nord-africains, no. 3 (1933): 247–62—the appellation “Algerian house” was rarely employed. Algérois referred to the geographic region of Algiers and not to the inhabitants of Algiers. Because Algeria was deemed a French department, the terms Arab, Berber, nègre, and indigène were used to designate the settlements in which the Algerian colonized population lived.

Annie Fourcaut, “Alger-Paris: crise du logement et choix des grands ensembles. Autour du XIIe Congrès national d’habitation et d’urbanisme d’Alger (mai 1952),” in Alger, lumières sur la ville, actes du colloque de mai 2001 à Alger (Algiers: Éditions Dalimen, 2004), 128.

Ibid., 131.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. R. Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 1–9.

The term “development” deserves an entire article in itself.

Cited in Annie Fourcaut, “Alger-Paris,” 131.

Marcel Lathuillière, “Algérie 1955,” UIA: Union Iternationale des Architectes, no. 7 (May 1955): 2.

Ibid., Fourcaut, “Alger-Paris,” 131.

Report by Marcel Lathuillière, “L’habitat des musulmans dans les villes d’Algérie,” Rapport du XIIe Congrès national d’habitation et d’urbanisme (Algiers, May 1952), cited in Ibid., 132.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Subject

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)