“Mere decorating,” we say without thought. The former modifies the latter with such frequency that the words appear natural together. In fact, the Cambridge Dictionary gives, as an example of the usage of the adverb “merely,” the sentence: “These columns have no function and are merely decorative.”1 A Google search for the twinned words “mere” and “decorating” turns up 1,420 results. Meanwhile, “merely decorative” has 166,000 results and “mere decoration” gets us another 155,000.

In architecture, this aspersive turn of phrase proliferates. It neatly summarizes one of the core tenets of orthodox modernism: the rejection of ornament. Before Adolf Loos railed against it, Hermann Muthesius called for “the elimination of every merely applied decorative form.”2 Le Corbusier writes in Towards a New Architecture, “We must clear up a misunderstanding: we are in a diseased state because we mix up art with a respectful attitude towards mere decoration.”3 Yet even after modernism, the phrase survives. In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas asserts that “[Le Corbusier] does not know that 10 Manhattan theories are only diversionary tactics, mere decorative dressing for the essential founding metaphors,” without interrogating his own deployment of another such diversionary tactic for a foundational metaphor.4 More recently, Christopher Hawthorne describes the Perot Museum in Dallas, Texas with these words in The Washington Post, while Edwin Heathcote claims, in The Architectural Review, that Grayson Perry and FAT’s House for Essex surpasses this condemnation.5

The verbal pairing surfaces as well in cultural discourse more broadly, extending far beyond architecture while inevitably referring back to it, even if just as metaphor. Clement Greenberg, unsurprisingly, makes frequent recourse to the phrase in his essays.6 Edward Said uses it in his introduction to Orientalism.7 Boris Groys takes advantage of it in “The Topology of Contemporary Art,” as does Susan Sontag in “On Style.”8 Hans-Georg Gadamer, in “The Ontological Foundation of the Occasional and the Decorative,” demands a revision of “the usual distinction between a proper work of art and mere decoration.”9 Even in Difference and Repetition, Gilles Deleuze writes, “The problem is not to direct or methodologically apply a thought which pre-exists in principle and in nature, but to bring into being that which does not yet exist (there is no other work, all the rest is arbitrary, mere decoration),” which is quoted by Elizabeth Grosz and Peter Eisenman in the epigraph for Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space.10

While this derisive phrasing stems in part from the refusal of ornament that characterized early modernist culture, it also precedes it. “A mere closet is here transformed into a stately room, by that regard for harmony of parts which distinguishes interior architecture from mere decoration,” write Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman in The Decoration of Houses in 1897.11 Before that, Friedrich Nietzsche discusses “the downfall of an entire merely decorative culture,” in “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life” from Untimely Meditations.12 Or, even further back, G.W.F. Hegel writes in the second section of volume two of Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, “Just as in the case of architecture we made an essential distinction between buildings that were independent on their own account and those that served some purpose, so now here we can establish a similar difference between sculptures that are independent of anything else and those which serve rather as a mere decoration of spaces in or on buildings.”13

The last few decades have borne witness to a concatenation of efforts to rescue ornament from this denigration as excessive, from Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown to Farshid Moussavi and Mark Foster Gage. Broadly speaking, they constitute attempts to bring ornament, or decorative surface treatment, back into the purview of architecture. Excessiveness and affect are found to have “function.” What remains untouched, however, is that other component of the derision implicit in the “merely decorative”: namely, decorating itself. This is the condescension that precedes modernism, that seems to precede everything—the insignificance of the act appears so self-evident that there is no defense needed. “Decorative,” as an insult, appears to derive ultimately from a dismissal of “decorating,” the practice.

Yet the two cannot be separated: without architecture, there is nothing to decorate, and without decoration, architecture disappears into illegibility—neither navigable nor inhabitable. As such, they are impossible to define without making recourse to the other. While the work of the architect ends with construction, the inhabitant-cum-decorator must continuously maintain the home, adjusting it to suit new tastes. Decorating is the under-recognized labor that constitutes the interior as such through the placement and upkeep of objects and things, such as bibelots, carpets, and houseplants, within pre-existing built space.

Architecture is a profession and a discipline. It requires degrees, and therefore either pre-existing wealth or speculative income in the form of debt (at least in the United States) to legitimate itself. One must pass tests, get certified, and solicit patronage. Decorating, on the other hand, does not, so it is either professionalized as interior architecture or design or left at the door. Practiced by people of all classes and demographics, it is architecture’s pedestrian mirror. There is a classist sentiment here as well as—considering the common associations between decorating and women and gay men—undoubtedly sexist and homophobic undertones. But there is more than sentiment at play.

According to estimates from 2012, the home decorating market measures at around $65.2 billion each year.14 This doesn’t account for its share of the value of domestic labor more broadly, which isn’t figured in GDP calculations but, if it were, would raise them by nearly a quarter.15 And, likewise, such figures don’t account for the truly global reach of decorating today, which touches everywhere from the forests of the Amazon to the marble quarries of Italy to the sweatshops of Southeast Asia. This economy is obscured in shadows cast by derision. What is so mere about something that has such economic value, that nearly everyone in the world does? More importantly, what is the function of this aspersion, and how does it operate?

H. Paterson (maiden name of Helen Paterson Allingham), Gathering Ferns, 1871.

Languages of Flowers and Ferns

Alongside gardening tips and lists of newly-discovered plant specimens, the September 1867 edition of The Floral World and Garden Guide documents the unfortunate death of a Miss Jane Meyers in its “News of the Month.”16 The young woman was traversing Craighill, a large cairn near Blairgowrie in Scotland, on her way to the waterside, when she, “being fond of botanical specimens,” stopped to collect a fern. As she bent down to grab it, enchanted, perhaps, by the curling tendrils themselves or by their popularity in bourgeois social circles, the soil beneath her gave way and she fell into a chasm, plummeting a total of 170 feet to the ground below, where her ankle-bone dislocated and pierced through her skin. For six or seven hours Meyers lay on the moist ground, tormented by swarms of flies and other insects, before her accidental rescue. Three days later, she died.

Meyers’ death could be attributed to pteridomania, or fern-fever, a decorating trend that spread through Victorian England with such enthusiasm that it has been described as a “social mania.” Individuals would wander the countryside, looking for rare specimens and harvesting them for use as decoration. The plants littered stylish houses and their image made its way into ceramics, furniture design, glassware, and metalwork alike. Hundreds of books were written on the subject. Fern-fever generated a robust economy of its own, which reinforced existing gendered and class-based divisions of labor. Primarily seen as the purview of women, it was understood as a “hobby” for middle-class women, while also producing a market facilitated by members of the working classes who would engage in the more arduous and sometimes even deadly aspects of the practice. And it was responsible for not just the death of Meyers and professional fern collectors, but also the extinction or near-annihilation of Oblong Woodsia, Alpine Woodsia, the Killarney Fern, and the Dickie’s Bladder-fern.17

Like the rhizomatic roots of the fern, the trend proliferated widely, primarily due to two factors: an unprecedented increase in botanical guides and the invention of the Wardian case in 1829. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward, a fervent amateur biologist, maintained an herbarium of some 25,000 specimens but had difficulty keeping ferns in his London residence, where the toxic atmosphere of coal smoke and sulfuric acid poisoned the plants. Ward was also an amateur entomologist, collecting moths and their cocoons in glass vials. In one of these vials, he noted that a fern spore and grass seedling had accidentally taken sprout in the sealed container and were capable of surviving in the enclosed environment. Seeing the potential, Ward developed his eponymous case, the forerunner to the modern terrarium as well as aquarium, and thus, fern-fever was born.

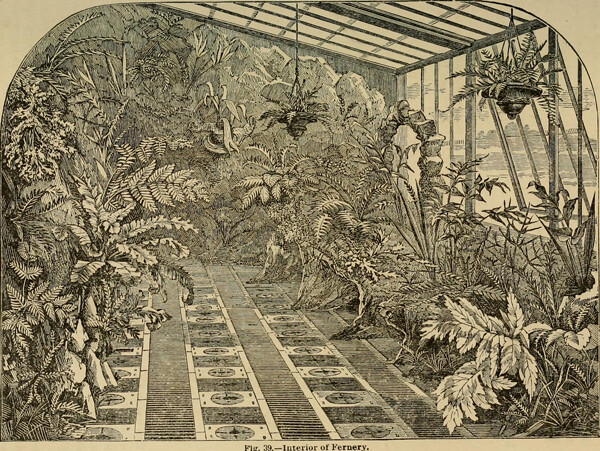

Wardian cases were like miniature glass buildings, often designed with Gothic arches and detailing. Inside, little landscapes and artificial “ruins” were created out of cork, pumice stone, or coke. Something of a small-scale forerunner to the great glass and iron structures of the era, their economy was propelled by the market novelty and trendiness of glass at the time. Sometimes, they took the shape of built-in window extensions. Some claimed that they had beneficial effects for psychiatric patients and for the working classes. “Window gardening (or Hortus fenestralis) originated in Europe and entailed either filling a bay window with plants or attaching a projecting glass case to the exterior of a sash window,” writes Sarah Whittingham, author of The Victorian Fern Craze. “It was particularly recommended for the working classes as the vegetation hid bad views or substituted for no view at all.”18 Placed primarily in the parlor or drawing room, their maintenance was understood as the job of women, part of a broader “Domestic Floriculture.”19 When taken to further extremes, Wardian cases were enlarged to full-size ferneries, replete with an architecture attuned to the specific needs of the plants (“abundant space, a pure atmosphere, a variety of surface, natural shade, and a natural fall of water”).20 In other words, architecture conformed to the trend, both at a small scale—with the modification of a window sill—or large—by building an extension to the home. Rather than architecture preceding decorating, as it is typically thought to, here a decorating trend constructed an entirely new architectural typology.

Henry T. Williams, Window Gardening: devoted specially to the culture of flowers and ornamental plants for indoor use and parlor decoration, 1872

Botanical guides have their own history. Modern botany was born in the nineteenth century through the establishment of a division between botanical appreciation as a hobby and as a science. Even in the eighteenth century, finding and documenting plant specimens was a popular pastime, particularly among women. “Botany came to be widely associated with women and was widely gender coded as feminine,” writes Ann B. Shteir.21 This was encouraged through books such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Letters on the Elements of Botany Addressed to a Lady, which contributed to shifting gender norms of the time.22 “Many things, which were thought to be above their comprehension, or unsuited to their sex, have now been found to be perfectly within the compass of their abilities, and peculiarly suited to their situation,” writes Maria Edgeworth, an Anglo-Irish writer who pioneered the modern European novel. “Botany has become fashionable; in time it may become useful, if it be not so already.”23 This, however, was not immune to resistance: “when Ladies enter into political contention, or devote their lives to study, they throw off the female character,” writes John Burton in Lectures on Female Education and Manner.24

This conflict between botany as a feminized hobby and botany as a study—in other words, the purview of men—led to a bifurcation of the practice, part of a larger trend at the time towards the formalization of disciplines contra pastimes. “Hierarchies of value and authority emerged, such that the ‘botanist’ was distinguished from the ‘botanophile,’ the ‘scientific Florist’ from ‘the general reader,’ and ‘love of botany’ from ‘love of flowers,’” writes Shteir.25 The Linnean system of classification, which focused on identification and classification based on reproduction, was easy-to-use and had been taught to women through guidebooks intended to encourage interest in botany. By the mid-nineteenth century, “professional” botanists began to dismiss the Linnean system in favor of analyses of plant structure, in part because of the association between the system and women. In creating a new framework of knowledge production, women were largely sidelined and ostracized from the emerging professional field. John Lindley, one of the main proponents of this shift, disparaged the Linnean system as being responsible for making botany an “amusement for ladies rather than an occupation for the serious thoughts of men.”26 While Lindley published books for women, they relegated women into a separate sphere and were rife with condescension, such as the statement that botanical study by women was not for science, but rather for the education of their “little people.”27

According to Shteir, this was not the only textual division between botany as science and hobby. The move towards scientizing the discourse around botany was in part a reaction to the prevalence of two literary forms associated with women: pressed books and the “language of flowers.” The former comprised taking plant specimens and placing them between the leaves of a book. It was a highly popular practice, particularly among upper class women. Charlotte Bronte was a fan, and Charles Dickens satirized it in David Copperfield.28 While these collections were later found to have archival value, and helped familiarize practitioners with the various species of ferns and flowers, at the time they were widely disregarded as a frivolous pursuit. Meanwhile, the “language of flowers” comprised a coded discourse that was also associated with women. Various flowers and plants were associated with certain meanings and were often a means of romantic exchange. Bouquets formed complex symbolic arrangements. Ferns were said to suggest discretion and secrecy, with sexual undertones playing off their unusual reproductive systems, which involve neither seeds nor flowers. Popular botany, and by extension decorating, could be added to what Michel Foucault describes in the first volume of The History of Sexuality as “the variety, the wide dispersion of devices that were invented for speaking about [sex], for having it be spoken about, for inducing it to speak of itself, for listening, recording, transcribing, and distributing what is said about it: around sex, a whole network of varying, specific, and coercive transpositions into discourse.”29

In fact, there are many sexual connotations with pteridomania. Even fern names carried suggestive implications: ”Venus’s hair” were so-called due to their supposed resemblance to women’s pubic hair. “Botanising is not a bad way of getting over the afternoon, and if you can get your basket well fernished so much the better,” read a humorous report in the satirical magazine Punch.30 “And it is a well-known fact that the rarest specimens grow in the least frequented spots, so you and your blooming companion can—but the hint is sufficient.” In other words, pteridomania contributed to the production of images of female sexuality in Victorian times, here exemplified through an ironic attitude towards its supposed enabling of romantic trysts. This dynamic, alongside the sexualization of the “language of flowers,” echoes what Foucault calls the “hystericization of the female,” or the belief that women are “thoroughly saturated with sexuality.” Decorating can therefore be understood as yet another area of the historical production and regulation of sexuality. “It is worth remembering that the first figure to be invested by the deployment of sexuality, one of the first to be ‘sexualized,’ was the ‘idle’ woman,” Foucault writes. “She inhabited the outer edge of the ‘world,’ in which she always had to appear as a value, and of the family, where she was assigned a new destiny charged with conjugal and parental obligations.”31 Discipline and decorate: the construction of subjectivity takes place even in the most innocuous of locations.

Coursing through these discourses surrounding pteridomania is an attitude that could be described as something like a supercilious tolerance for behavior deemed insignificant paired with a condescending account of its imagined value. The man who coined the term “pteridomania,” Reverend Charles Kingsley, writes in his 1855 book Glaucus; Or, the Wonders of the Shore:

Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing “Pteridomania,” and are collecting and buying ferns, with Ward’s case wherein to keep them, (for which you have to pay), and wrangling over unpronounceable names of species, (which seem to be different in each new Fernbook that they buy,) till the Pteridomania seems to you somewhat of a bore. and yet you cannot deny that they find an enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet and Berlin-wool. At least you will confess that the abomination of “Fancy-work”—that standing cloak for dreamy idleness (not to mention the injury which it does to poor starving needlewomen)—has all but vanished from your drawing-room since the “Lady-ferns” and “Venus’s hair” appeared; and that you could not help yourself looking now and then at the said “Venus’s hair,” and agreeing that nature’s real beauties were somewhat superior to the ghastly woollen caricatures which they had superseded.32

Kingsley denigrates women’s ability to understand science, describing their “wrangling” over terminology, as well as the legitimacy of the texts used to support their interest. He condescends towards the culture, as well as other domestic labors, from crocheting to “fancy-work,” a term encompassing a wide variety of practices such as embroidery. Kingsley also implicitly acknowledges the class distinctions in domestic labor, as he writes of “poor starving needlewomen.” These class distinctions were maintained in the context of pteridomania, rendering apparent leisure into clear labor. One book on the subject decries figures called “The Itinerant Fern Vendor” and “Professional Fern Tout” as peddlers of ferns who contributed to the ecological destruction that accompanied the decorating trend.33 Meanwhile, a painting by Charles Sillem Lidderdale depicts a young working class woman, a fern-gatherer, with a forlorn look on her face, a bundle of ferns on her back, and a fern sampling in her hands. In a painting by Robert Herdman, a fern-gather no older than ten stares at us sheepishly, pulling away from the viewer and lifting her shoulder as if it were a shield. In fact, according to contemporary sources, many of these working class fern-gatherers were children.34

But it would be a mistake to disregard the bourgeois side of things as purely leisure. Embedded in the name “fancy-work” is the implicit understanding that the maintenance of the home, including its decoration, constitutes work. Fancy work facilitated the production of the interior, the delineation of private spaces from spaces of work. “The private individual, who in the office has to deal with reality, needs the domestic interior to sustain him in his illusions,” Walter Benjamin writes of the nineteenth century bourgeoisie.35 Benjamin describes the “collector”—a male figure, despite the fact that women too collected (ferns, for example)—who “makes his concern the transfiguration of things. To him falls the Sisyphean task of divesting things of their commodity character by taking possession of them.”36 But nothing is said of the women responsible for the “coverlets and antimacassars, cases and containers” that litter the nineteenth century, bearing the traces of life that Benjamin says define a dwelling against other spaces. Nothing is said of the transfiguration of a house into a home, or the fact that, for women, the house was hardly detached from labor. And nothing is said of the sweeping, dusting, cleaning, and arranging required to make collected objects appear divested of their commodity character.

While unpaid, uncounted, and unnoticed, such work helps a house become a home, and thereby enables both the production of social capital for the men residing within as well as, undoubtedly, increasing the value of the asset in the real estate market. A well-decorated home, rendered in accordance with the latest tastes, as any stager or prospective seller knows, sells better than an empty one. Still, Kingsley describes the labor as a “standing-cloak for dreamy idleness.” Moreover, even the media through which this labor was learned—the guidebooks mass-produced and heavily promoted to women—is denigrated. The means—Wardian cases and books—are branded as excessive. Here, an entire domestic economy is reduced to “somewhat of a bore.” In short, domestic labor requires a veneer of leisure in order to function as invisible and unpaid. This condescension is, at its core, a relationship to labor and a means of disciplining the laborer. When domestic labor is understood as such, the home is revealed to be a factory, and the production of this superstructural attitude, this culture of condescension, lubricates its cogs.

The Year of Greenery

To announce “greenery” as its 2017 color of the year, Pantone released a slick video saturated in the hue. In it, the type of cheery tune that often accompanies corporate videos plays alongside seductive images of a cast of models surrounded by vegetation, primarily houseplants such as banana palms and philodendron. Intended to signal, as its title suggests, an aspect of the zeitgeist, the video and color choice reflect what is elsewhere described as a widespread trend for houseplants in decorating, which is ostensibly specific to the “Millennial” generation.

“Are Millennials Obsessed With Houseplants?” asks Jezebel, while Cosmopolitan endeavors to get “to the Root of the Millennial Plant Obsession.”37 The Telegraph recently published “Green revolution: how the houseplant became hip again,” and elsewhere, “How houseplants charmed a new generation of gardeners.”38 “Why millennials are becoming proud plant parents” reads a headline in The Toronto Star, and The Olympian published “Millennials take their turn at gardening.”39 There is, according to Horticulture Week, a “houseplant boom,” but they state that the market has yet to peak.40 While fiddle-leaf figs have been reported as among the most popular plants, the 2017 trend is, if these articles are to be believed, for ferns.41

Just like with pteridomania in the nineteenth century, this new-found phytomania comes surrounded with a particular discursive framework that reflects the specific and dominant concerns of the era. For some, with reports that filling your house with plants may help clean the air, the trend reflects an anxiety about climate change and the broader ecological state of things. A 1989 study by NASA listing the plant species that are most beneficial for one’s health has recirculated recently with fervor, such as in The Wall Street Journal.42 These, just like the supposed, gendered benefits of fern collecting, constitute one of the primary means by which a labor is disguised as something else. Owning a houseplant first entails research, then selection, and then the unceasing labor of maintenance—watering, pruning, fertilizing. Just like with ferns, houseplants certainly have an aesthetic value, but they are today considered to have more than just that, improving the owner’s very body as well as their relationship to a broader ecology. In this, the trend could be considered part of a larger cultural movement towards endless self-improvement and self-edification through consumption, both of plants themselves and of their aesthetic. Accompanying articles about the health benefits of houseplants are images of well-decorated homes filled with them. The trend is, in other words, intentionally marketed, less to facilitate a horticultural economy and more as part of a larger economy of home decorating. Little attention is given to the role of the plants in increasing the value of the home or towards their own market. Promotional material surfaces in traditional media, such as print magazines, but, most notably, online. Where fern-fever was facilitated by the invention of botanical guides, today’s plant mania is spread, primarily, through new digital channels, and in particular, Pinterest.

“Pinterest is about who you want to become,” states Evan Sharp, its co-founder, in an interview with Creative Times.43 “It helps you build the life you want to lead, brick by brick.” The architectural metaphor is not accidental. Not only did Sharp study as an architect and develop the platform for his architect friends, Pinterest is most widely used in connection to physical space. According to the business intelligence firm RJ Metrics, 17.2% of all pins are categorized as “Home,” followed by “Arts and Crafts” at 12.4%.44

Decorating is assumed to be more personal and less formalized than architecture. We express ourselves in how we decorate. We construct our homes, that most (ostensibly) personal of contexts. We do not decorate according to dictates. Yet, nonetheless, decorating doesn’t happen in a vacuum—as both Pinterest and pteridomania exemplify. Trends construct the borders of our capacity to personalize space. Decorating is the accumulation of various outsourced ideas, filtered and personalized by the individual subject. As Sharp said, it is a means of projecting one’s idealized version of the self. Ipseity is always constructed through alterity, even formally-speaking; or in other words, we are a composite of outsourced parts and so are our homes. If pteridomania played a role in the nineteenth century figure of the hystericized “idle” woman, Pinterest serves to facilitate the construction of the neoliberal “entrepreneurial self,” or, as Wendy Brown states, the process that “casts people as human capital who must constantly tend to their own present and future value.”45

Elsewhere, the trained-architect-turned-tech-mogul Sharp describes Pinterest as “all about browsing” and “solving the human problem of discovery.”46 Through interface design, Pinterest endeavors to make legible the vastness of the internet. Its algorithms are the Wardian cases of today, enabling new trajectories and faster velocities for the transmission of trends. Its database functions like botanical guides, while the individual user’s pins parallel the pressed books. Fundamentally, Pinterest is tethered to the real world, to discovering activities and objects that you can do offline as well. “It’s about things you didn’t even know you were looking for,” Sharp says, “and helping you encounter those things in your daily life.”47 Just like nineteenth-century botanical guides, Pinterest serves as a means to learn more about the world. But it is, likewise, not divested of a telos. This is not idle wandering. We pin things in order to replicate them or purchase them—or in order to dream of doing one or the other. According to a Millward Brown Study, eighty-seven percent of Pinterest users have purchased something they’ve seen on Pinterest, while 93 percent intend to do so. “Discovery” and self-edification mask the economic role of Pinterest.48

Importantly, Pinterest is dominated by women. Of the 150 million Pinterest users in the world, a full 81% identify as female. In fact, 45% of all adult women in the United States use the platform.49 Meanwhile, domestic labor continues to be heavily divided by gender. 95% of paid domestic laborers are women.50 Because it is rarely quantified, it’s hard to determine the exact breakdown of unpaid domestic labor, but studies show that women spend nearly twice as much time on “housework” than men in the United States. If the 81% of Pinterest users are women, and more than a quarter of pins are related to the “home” or “arts and crafts,” then Pinterest can be understood as a means of facilitating unpaid domestic labor, whether by introducing decorating trends to follow or strategies to DIY improve the home. The site is replete with cleaning tips and “lifehacks,” which are little more than shorthand for strategies to reduce domestic labor through special tricks. Interestingly, lifehacks are almost always alternative ways of using common household objects, such as bottle caps or cleaning agents. They constitute an idealized image of a hermeneutic economy of the home, in which its maintenance is facilitated internally—an entirely self-contained and self-sufficient environment like Fourier’s Phalanx in the form of a suburban home.

Meanwhile, DIY’ing, like fancy work, is both derided as light and unserious, and celebrated in that it serves as a diversion. Both have been defined in opposition to the representational paradigm of commodity production at that time: the former is valued for producing an “expensive look” by cheap means, specifically recycling and bricolage, and the latter was said to make an interior more homey, in contrast to the recent introduction of mass-produced furniture and household objects. But while dismissed as frivolous, both have an explicit economic function.

Just like the Victorian fern collector, the assumedly female DIY’ing Pinterest user helps facilitate the economy of the home. That is to say, her work raises the value of the home, and the more crafty the upcycling, the greater the profit. In an era in which the housing market has a primary role in the economy, this work reflects the “ideology of homeownership” marked by the association of “home with comfort and achievement, on the one hand, and with labor and investment, on the other,” as the media theorist Shawn Shimpach writes.51 Similar to in Victorian times, DIY’ing often serves to offset the apparent sterility of mass-produced commodities through handicraft. And, again, it is used to create an appearance of affluence, rendering the home both a representation of and a mechanism for the aspirational mentality of its neoliberal inhabitant.

While less explicitly misogynistic, the Pinterest user faces much of the same condescension as the Victorians. “Pinterest is the hottest new social-networking tool,” writes Petula Dvorak for The Washington Post.52 “And it’s digital crack for women.” Appropriate for an era in which individuality is prized above all, the main criticism of those who follow Pinterest is a lack of “originality.” As Amanda Sims writes in Architectural Digest, “Avoid the Pinterest House like you do your creepily perfect neighbor who claims to like the taste of green juice, and embrace your inner oddities instead.”53

For design critics, heterogeneity is everything. But heterogeneity is hard—and it doesn’t exactly sell. In short, a trend constitutes a means of navigating the intellectual component of decorating as labor. Faced with an infinite amount of choices of what to hang and where, the individual follows formulas laid out by others. In so doing, the home accords with norms and therefore has an economic—as well as social—value. Go it entirely your own way, and chances are you’ll be putting people off. The best-decorated homes appear to be those that both conform to the trend while slightly bucking it, as if to state rhetorically that the resident adheres to social norms while still projecting individuality—the ideal of today. A trend is, quite simply, how one survives the unceasing labor of maintaining a home. And following them is far from easy, requiring the intellectual work of researching, collecting, and re-presenting.

Like the critic, the architect disdains the decorator for the visibility of the trend. Of course, architecture also follows trends in both thought and form, but vast reserves of energy are expended to mask this. Novelty is prized above all, even if the newest forms relate to one another like mutated viruses. One could argue that the primary economic role of architecture is to create new terrains for the expenditure of surplus capital through the establishment of new formal tastes: an unending cycle of demolition and production fueled by fashion. Even with suburban tract homes, identical to one another in almost every way, the most recent trend—Cape Cod, ReModern, Tuscan, etc.—mandates new construction. But for these new forms to function, especially in the case of more avant-garde architectures, the interior must conform to the norm. In almost every case, the (lavishly, professionally decorated) interior of a starchitect-designed luxury apartment could be swapped with another. Without decorating, the economy of architecture would falter. The architecture-decorating dyad isn’t just conceptual but also material. Decorating produces a projection screen for one to imagine living in a new space. Architecture constructs and instructs daily life, but it is decorating, by way of the trend, that normalizes it, that allows it to slip into the background. And this process demands workers—disciplined to the point where the discipline itself becomes invisible.

There is not a straight line from pteridomania to today’s phytomania. The culture surrounding each corresponds to the dominant socioeconomic and ideological paradigms of the era, whether surfacing as a means to control the hystericized female or as a means of self-edification for the neoliberal subject. Yet the former haunts the latter; Pinterest contains hundreds of thousands of results for ferns and many for fern-mania itself, serving as inspiration to decorate the homes of today. A cloak of condescension and diminution stretches across time, conforming to specific contours of each time period. Beneath it lies a variegated field of labor, rendered invisible and therefore uninterrogated. The architect may raise the structure, but is the unpaid, unprofessionalized decorator that divests it of its commodity character and makes it a home.

Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. “merely,” ➝.

Adolf Loos, “Ornament and Crime,” in Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays, ed. Adolf Opel (Riverside, CA: Ariadne Press, 1997); Hermann Muthesius, Style-Architecture and Building-Art: Transformation of Architecture in the Nineteenth Century and its Present Condition, Texts & Documents (Los Angeles: the Getty Center Publications Program, 1994), 79.

Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture (London: Dover, 1986), 95.

Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retrospective Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1994), 279.

Christopher Hawthorne, “Dallas’s Perot Museum: Design as mere decoration,” The Washington Post, March 30, 2013; Edwin Heathcote, “The problem with ornament,” The Architecture Review, September 3, 2015.

See: “Sculpture in Our Time,” in Clement Greenberg: the Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1993), 55.

Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Routledge & Kegan, 1978), 33.

Boris Groys, “The Topology of Contemporary Art,” in Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity, ed. Terry Smith, et al. (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), 79; Susan Sontag, “On Style,” in Against Interpretation (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966).

Hans Georg Gadamer, “The Ontological Foundation of the Occasional and the Decorative,” in Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory, ed. Neil Leach (London: Taylor & Francis, 2005), 130.

Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, The Decoration of Houses (London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897), 172.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life,” in Untimely Meditations, ed. Daniel Breazeale (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 123.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, Volume II (London: Oxford University Press, 1975), 765.

Jessica Bossari, “Growth of the Home Decor Market Shows No Signs of Slowing Down,” Forbes, October 24, 2012, ➝.

Bryce Covert, “Putting a Price Tag on Unpaid Housework,” Forbes, May 30, 2012, ➝.

“News of the Month,” in The Floral World and Garden Guide, ed. Shirley Hibberd (September 1867): 287.

Wikipedia, s.v. “pteridomania,” ➝.

Sarah Whittingham, The Victorian Fern Craze (Oxford: Shire Books, 2009), 25.

Ibid., 23.

Edward Newman, A History of British Ferns (London: John Van Voorst, 1840), xi.

Ann B. Shteir, “Gender and ‘Modern’ Botany in Victorian England,” Osiris 12 (1997): 29.

Emanuel D. Rudolph, “Women in Nineteenth Century American Botany; A Generally Unrecognized Constituency,” American Journal of Botany 69, no. 8 (September 1982): 1346.

Maria Edgeworth, Letters for Literary Ladies, ed. Claire Connnolly (2nd edn. 1798; London: J. M. Dent, 1993), 21, quoted in Rudolph, “Women in Nineteenth Century American Botany,” 1346.

John Burton, Lectures on Female Education and Manners (Dublin: J. Milliken, 1794), quoted in Rudolph, “Women in Nineteenth Century American Botany,” 1346.

Ibid., Shteir, 31.

John Lindley, Introductory Lecture Delivered in the University of London on Thursday, April 30, 1829 (London: John Taylor, 1829), 17, quoted in Shteir, 33.

John Lindley, Ladies’ Botany: or, A Familiar Introduction to the Study of the Natural System of Botany (London: James Ridgeway, 1834–1837), quoted in Shteir, “Gender and ‘Modern Botany,” 35.

Deborah Lutz, The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects (New York: W. W. Norton & Company).

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books), 34.

Ibid., Whittingham, 13.

Ibid., Foucault, 121.

Charles Kingsley, Glaucus; or, The Wonders of the Shore (London: Macmillan and Co., 1859), 4–5.

Ibid., Whittingham, 19.

Ibid., Whittingham, 19.

Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in The Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 8.

Ibid., 9.

Matthew Appleby, “Houseplants: The Fastest Garden Centre Growth Sector?” Horticulture Week, July 20, 2017, ➝.

Lauren Smith, “Ferns Are Winning the Houseplant Popularity Contest,” HouseBeautiful, March 24, 2017, ➝.

Megan McDonough, “These Five Plants Don’t Just Look Good — They Improve Your Health, Too,” The Washington Post, November 9, 2016, ➝.

Evan Sharp, Interview with Patrick Burgoyne, “Pins and pixels: an interview with Pinterest Co-Founder Evan Sharp,” Creative Times, October 4, 2016, ➝.

Lauren Indvik, “What People Are Pinning on Pinterest,” Mashable, March 12, 2012, ➝.

Wendy Brown, Interview with Timothy Shenk, “Booked #3: What Exactly Is Neoliberalism?” Dissent Magazine, April 2, 2015, ➝.

Evan Sharp, “Designing Discovery,” The Next Web, June 12, 2015, ➝.

Ibid.

Rachel Eisenberg, “Pinterest and the Power of Future Intent,” Millward Brown, May 12, 2015.

Salman Aslam, “Pinterest by the Numbers: Stats, Demographics & Fun Facts.” Omnicore, January 23, 2017, ➝.

Sarah Ruiz-Grossman, “95% Of Domestic Workers Are Women. In California, They’re Demanding Better Pay.” Huffington Post, March 8, 2016, ➝.

Shawn Shimpach, “Realty Reality: HGTV and the Subprime Crisis.” American Quarterly 67 no. 3 (September 2012). ➝.

Petula Dvorak, “Addicted to a Web site called Pinterest: Digital crack for women.” The Washington Post, February 20, 2012, ➝.

Amanda Sims, “Beware the Pinterest House.” Architectural Digest, August 3, 2017, ➝.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Category

Positions is an initiative of e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)