Athens used to be small town. In 1922, following the war the Greeks lost against Turkey, she was asked to take in a large part of the 1.2 million refugees from Asia Minor. The refugees were placed in camps outside the city, which in time grew into suburbs, all named after the places the displaced Greeks left behind: Ionia, Smyrna, and Philadelphia all used to be towns on the coast of Turkey, and in Athens, they were all New. Athens became a city of refugees, and as she struggled to deal with the urgent housing demands of becoming New, in August of 1923, the government announced the first of many legislations regarding the illegal construction of buildings. Any construction to take place outside the official map of the city was officially deemed unauthorized, or “afthereto,” as the legal wording went. Yet rather than struggling to keep all buildings legal, Greek governments have, after realizing that the legalization process for the houses that the refugees built for themselves could be a significant source of income, turned a blind eye to unauthorized construction, and then charging supplementary fees to allow such buildings to become legal. The law of afthereta is one of the most revised pieces of legislation in Greek law, with every few years the ministries announced the impending demolition of all unauthorized structures, sometimes actually demolishing a few, followed by the announcement of yet more supplementary fees to legalize those buildings and bring them up to code. Through the refugee crisis of 1922, Athens became a new city of afthereta, the almost-government-approved unauthorized construction. A city of refugees left to their own devices; a city where it was ok to be illegal, as long as you bribed the state.

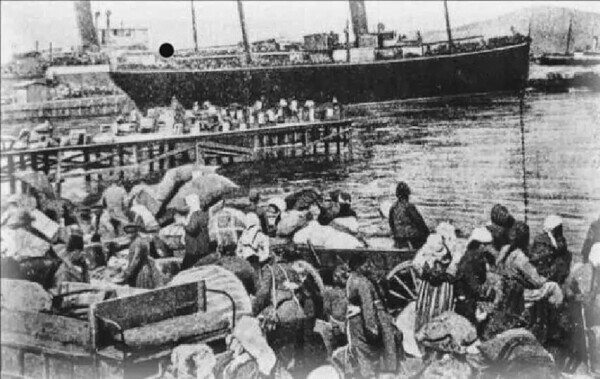

Photograph of Greek refugees fleeing Asia Minor, August, 1922.

A second wave of migration took place after World War II and the ensuing civil war where the Greek Government, supported by the Allied forces of the US and UK, managed to fight off the communist-supported Democratic Army of Greece in what Wikipedia calls the first proxy war of the Cold War. The countryside was ravaged and new masses of Greeks flocked to the capital seeking jobs and a viable future. Athens appeared to be in the process of being reborn. Housing was again in dire need, but by then the official map of Athens had expanded to include all those refugee camp suburbs. While unauthorized construction continued, especially in the western, working class suburbs, the bulk of housing came to be via a curious procedure called “antiparochi,” a system of exchange which the government sponsored through tax benefits. With antiparochi, all you had to do was give your land to a civil engineer who would build a polykatoikia—a small apartment building—within which you would be given two apartments. The rest of the other apartments would be split up between the civil engineer and the financial backer. Thus, as if by some Jesus fish magic trick, single family homes became polykatoikias, ready to host the new population of Athens; masses furiously arriving from all over Greece. Athens thus became a European metropolis, full of brand new modernist buildings, all of which were based on Le Corbusiers’ dom-ino frame.

It was not until the 1970s that we realized that instead of a proper modernist city, Athens was becoming a nightmare of sorts. With minimal government planning, Athenians had once again been left to their own devices and at the mercy of profiteering engineers. Antiparochi construction had been cheap and fast. All the buildings were derived from relatively small pieces of land, so they became increasingly small, unorganized, and uncoordinated blocks of flats clumsily glued together. Compared to other European cities, where modernism produced neat rows of identical, coordinated housing blocks, Athens appeared as a folklore patchwork of modernist ideals gone crazy. The new metropolis that resulted from the victory of the NATO forces was not looking very American, perhaps not even so Western. For years, we thought that this uncontrolled growth of the city was just a result of war, but recent studies have begun to suggest that the investment of Marshall Plan funds almost exclusively into the capital actually intended to drain the communist countryside of its population and bring it to Athens where it would be much more manageable. Greece was, after all, crucial to NATO; along with Turkey, it blocked the Soviet Unions’ access to the Mediterranean. NATO therefore could not afford Greece backflipping into the USSR. And so the rapid blooming of Athens is coming into historical focus as just a cold war political scheme. The city had been tricked, even manipulated into housing half of the country’s population. And antiparochi, together with reinforced concrete frame construction, became the tools for this operation.

Lottery for a mediocre building

Athens, as it exists today, is mostly the result of these two political crises: the loss of Asia Minor and the civil war. Each brought a wave of new inhabitants to the city along with a new procedure. Even though afthereto and antiparochi have almost died off, their effect on the buildings and people of Athens have left deep scars. Imagine you are a building ready to house a family who just lost everything, who ran from an immense fire on the coast of Turkey, and the government shows up and labels you unauthorized. Or, imagine that you are a neoclassical villa, or even a small family home surrounded by a flower garden, and a civil engineer shows up and replaces you with an apartment building that leaves no room for fancy. Do the buildings of Athens remember this drama? What kind of traumas did they sustain during these forced expansions, or as we call them today, developments?

Afthereto and antiparochi have produced some unexpected results. Afthereto became an instantly recognizable building typology, even if it was to be initially mocked. Due to particular loopholes in the legislation, one did not have to pay property tax for the unfinished building, and tax was calculated based on the floor area of the completed building. This resulted in families building concrete frames and only completing the floors that they really needed. As their kids grew up, maybe ten or even twenty years later, they would complete another one, and so on and so forth. With time the building became fully grown, but one could tell that it was not “designed.” Instead, the building was just a response to circumstance. Afthereta are mostly derided as a kind of strange folklore modernist patchwork of a building, yet on closer inspection, they are miraculous; almost the perfect building. Imagine a building that competes itself as the needs of their inhabitants arise; they produce no surplus space and they need no loans or large investments because they follow their families fortunes. By being built as their families grow, they become records of their family’s history. One might even say that they become portraits, where you can see that the kids grew up to become adults and formed their own families; the detailing on one floor might be from the 1970’s and on another from 1980s, so you know when the kids became adults and got their own floor. And because the afthereta procedure allowed, even suggested, that families all live in the same building, by extension these buildings formed a society that is family-centric, where the kids live under the same concrete frame structure as the parents and the grandparents. Afthereta reclaimed the concrete frame from the cold war manipulations that brought it into action, and turned it into an architectural portrait of Greek society.

At the same time antiparochi produced a city first seen as terrible and unlike most of its European friends, the uniform blocks of modernist Europe were gradually recognized as soulless, inhuman megastructure. Suddenly, the folklore collage of modernist leftovers of Athens appears exotic, even desirable.

Over the past sixteen years I’ve spent hours describing versions of this story to my analyst, explaining my take on the afthereta and trying to understand my relationship with Athens, which I have taken as a subject of study since I was a student of architecture. As I wondered why I was revisiting my earliest studies of unauthorized architecture for documenta 14, and why I was so fascinated with these buildings, my analyst replied: “Maybe because you were unauthorized as a kid too.”

He was referring to a moment in my childhood that I’ve discussed with him many times. I must have been four or five years old, and I decided to surprise my mom’s guests by putting on her most glamorous dress and walking into the living room where they were playing bridge. Instead of the applause I was fully working towards, I got the appalled reaction of her friends, some commenting that I should never do this again. My mom rushed me backstage, which was the kitchen in our polykatoikia, and explained that it was fine to wear her clothes and make-up between ourselves, but that other people didn’t appreciate boys playing with dolls or dressing up as their mom. This was the moment I understood that how I was, was not acceptable, not even allowed. And now, Mr. Bakirzoglou was saying that behavior was unauthorized, just like the buildings I was studying. Even though I understood that this was a classic Freudian-Lacanian-whatever wordplay, the idea that I was seeing myself in these buildings was an eye opener. Do buildings have personalities? Do they remember things and do they react to these memories? When I was looking at buildings, did I treat them as mirrors trying to find the right reflection, or was I interpreting them as strangers, looking for friends or lovers in the shape of a building?

I have often gone back to that moment at the age of five when I understood my behavior as unauthorized, or afthereto, as the moment when I kind of changed. Before then, I was free to be creative; it was fun to be fabulous and all I got was adoration. After that, I began to modify my behavior to fit whatever pattern was thought to be correct, even though I fully accepted, even enjoyed my own queerness. The reason I had been discussing all this with Mr. Bakirzoglou was to better understand the decisions I was making as an architect. For years, I had tried to maintain a proper studio and have what I thought was an architecture career, but after a series of personal dramas I decided to give it up and do whatever I wanted again. I was working towards understanding that whatever I wanted was to be that fully accepted, pre-unauthorized five-year-old who still believes it’s just fabulous to wear your mom’s dresses and everyone will love you for it.1

.png,1600)

Building in process (immature).

.png,1600)

Building in process (young).

Building in process (immature).

Being compared to a building I thought I was just studying for a project made me think of the entire city of Athens. The aftereto polykatoikies and the city itself might be a kind of folklore collage of modernisms, but was I not also one myself? A collage is a result of a process of adjusting, adding and subtracting, and hadn’t I been working on understanding and adjusting myself all these years? The almost-fifty-year-old me isn’t a product of immediate design, but of an ongoing process and adaptation to circumstance. Now I’m really beginning to confuse buildings with cities and people; me as an afthereto building, the afthereto as a portrait of a family and even of society itself. Where could this line of thinking lead? Me as a city? Do we see these characteristics in buildings because we want to, or do these buildings make us see them because we grew up in them? Does society become family-centric because of the buildings of its cities, or do the buildings cater to a psychological need, repairing the trauma of being displaced by keeping everyone together?

Psychoanalysis is often described by analysts as the interior design of the soul. You rearrange the furniture of your soul, change the places where memories sit, and what they spend their time looking at. Maybe you demolish walls to connect events from the deep past in the back of the space, to recent events in the front. Sometimes you try to make open plan spaces where everything is visible and out in the open, other times you realize that some memories need to be put into storage, disposed of even. But if psychoanalysis works so well for an interior space, could it perhaps be expanded to architecture? Psychoanalytic Urbanism? Could we analyze buildings the way we analyze ourselves, place them in the position of the analysand? And if we do, does the architect play the role of the analyst, or of the interpreter between the analyst and the building?

If we look at a city like Athens, we see that as much as the politics formed the city and its buildings, the resulting buildings helped form the society they housed. If the concrete frame together with the financial realities of the period encouraged families to live together under a series of concrete slabs, then these slabs designed a family-centric society where kids almost never leave home, and as a result never really revolt against their parents. How does that explain a city where riots are part of its daily reality? Does the city perform the rioting it was denied, because she grew up at such close proximity with parents and grandparents? And was I rioting when I decided to be more like my five-year-old self rather than the architect I was becoming? How does one riot against inherited notions of how to be? Do you burn down the buildings you encounter with your analyst, or do you move away and attempt to make new ones elsewhere? If we look at a city as an endless session of analysis, is it a group session where people break down in front of others, where they are forced to expose their weaknesses and their paranoias in public, across from their neighboring buildings.

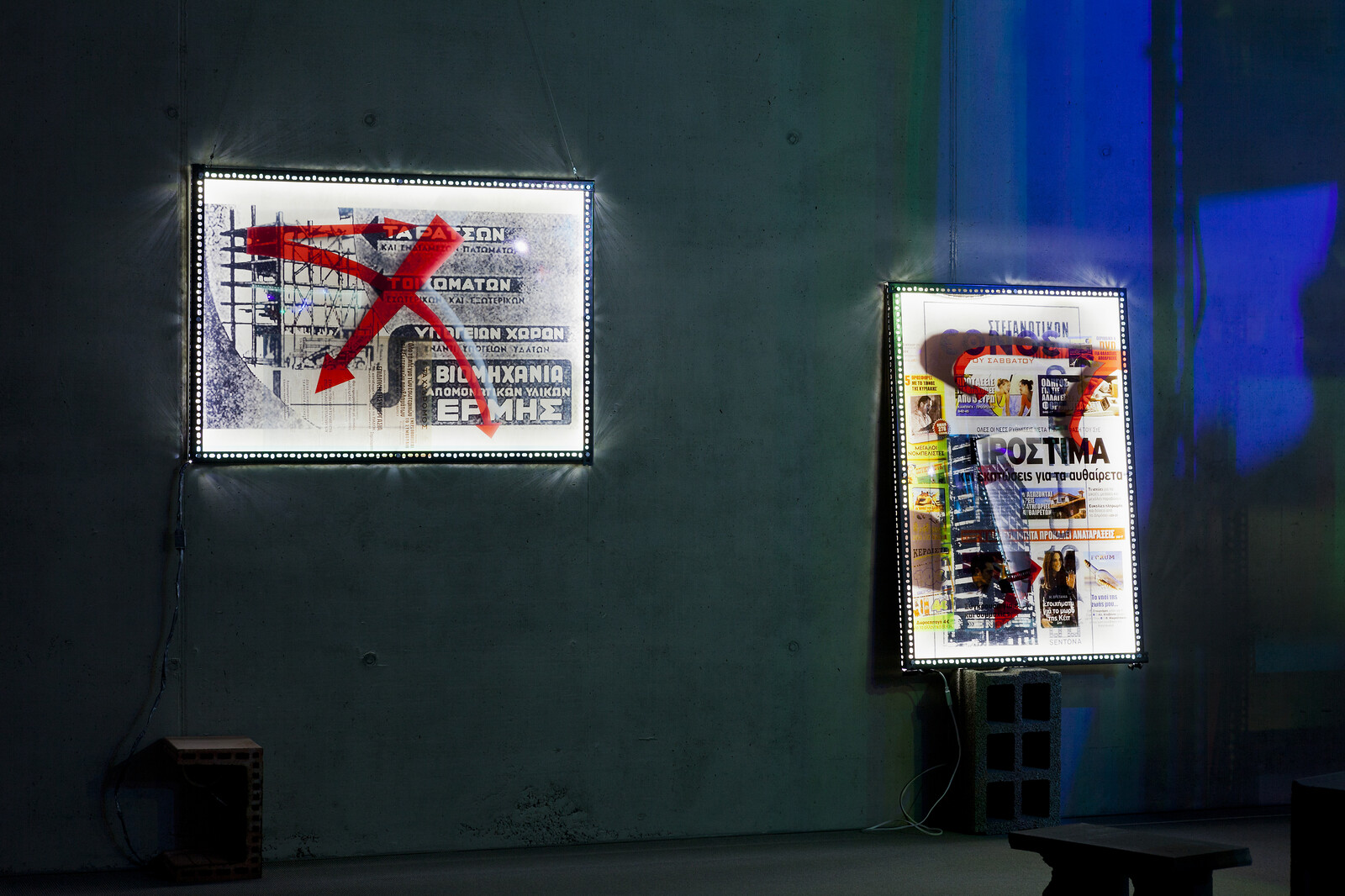

Installation view of Andreas Angelidakis, Unauthorized (Athinaiki Techniki), documenta 14, Athens, 2017. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

Installation view of Andreas Angelidakis, Unauthorized (Athinaiki Techniki), documenta 14, Athens, 2017. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

Installation view of Andreas Angelidakis, Ads for Athens, documenta 14, Kassel, 2017. Photo: Michael Nast.

Installation view of Andreas Angelidakis, Ads for Athens, documenta 14, Kassel, 2017. Photo: Michael Nast.

Installation view of Andreas Angelidakis, Unauthorized (Athinaiki Techniki), documenta 14, Athens, 2017. Photo: Giorgos Sfakianakis.

With time Athens kept on changing too. A third wave of migration came in the early 1990s, this time from Albania and the newly opened up Eastern European countries, then further migrations from Asia, and finally, at least for now, another refugee crisis following the ongoing war in Syria. But these events neither resulted in constructions nor into new procedures for the city. Migrations and crises were already part of her psyche; they were mere repetitions of past traumas. Athens today is a city of daily riots and never ending economic crises. She is largely unloved by its inhabitants, unless they are young internationals attracted by the hype of the international art world. Could one imagine, that with being borne out of political dramas and emergency situations, that Athens is an angry city?2 That it remembers that its first refugee buildings were called unauthorized, and its inhabitants tricked out of their family homes in exchange for mediocre apartments? Or that it was almost entirely populated by people who at some point lost their homes? Could it be that all through this, Athens developed her particular personality, one of continuously resisting, even rioting against how she should be? I can’t help but think of the kids downtown who almost every night set fire to trash cans, their behavior a mindless pattern developed through repetition, as somehow still expressing the anger of the city who was forced to become someone she wasn’t.

As I am writing this, I am fully aware of the extravagant ridiculousness of comparing refugee crises and cold war politics to being told by your mom not to wear her dresses in public, but still I persist because I am trying to be five years old again, and trying to imagine the architecture practice that a kid would have.

If we agree that Athens is an angry city that keeps protesting, could it be that’s why it seems to be becoming more popular by the minute? Could that be why documenta decided to visit, and why kids decide to stay? If there was one way to describe our time, it would be one of continuous protest, whether political, financial, or ecological; we always have to be against something, and perhaps Athens is the place to do exactly that.

Positions is an independent initiative of e-flux Architecture.

Subject

Positions is an initiative by e-flux Architecture.

(2014).jpg,1600)

,-2003,-srgb.jpg,1600)