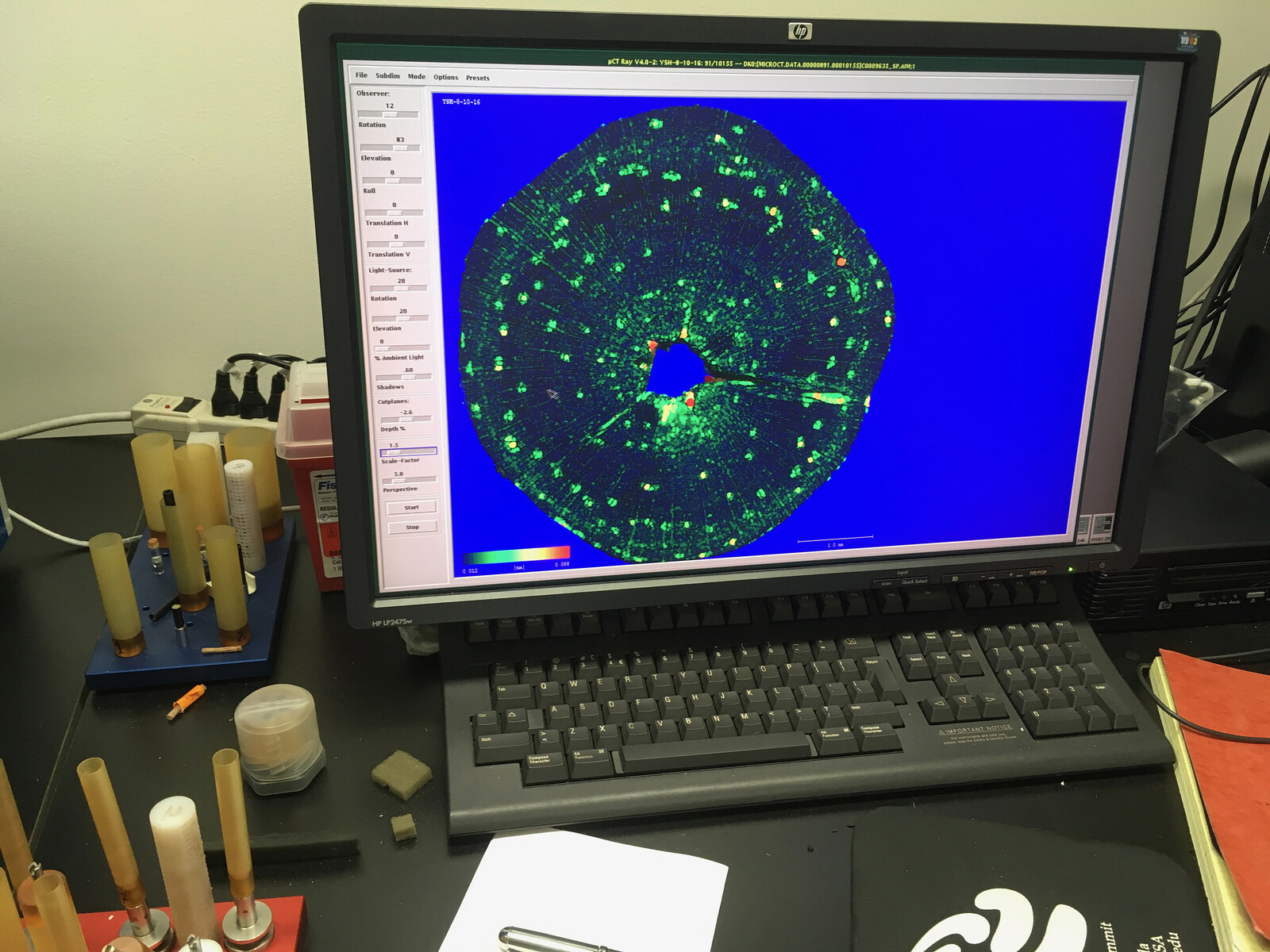

The more humans created a human-dominated world order, an order of life, the more we got rid of most of the wildlife that could have threatened it. And we developed mechanisms for dealing with “natural” disasters, ranging from technology to insurance. The only predators we have left now are viruses, bacteria, and other microbes. In a way, this happened by combining caring with scaling up.

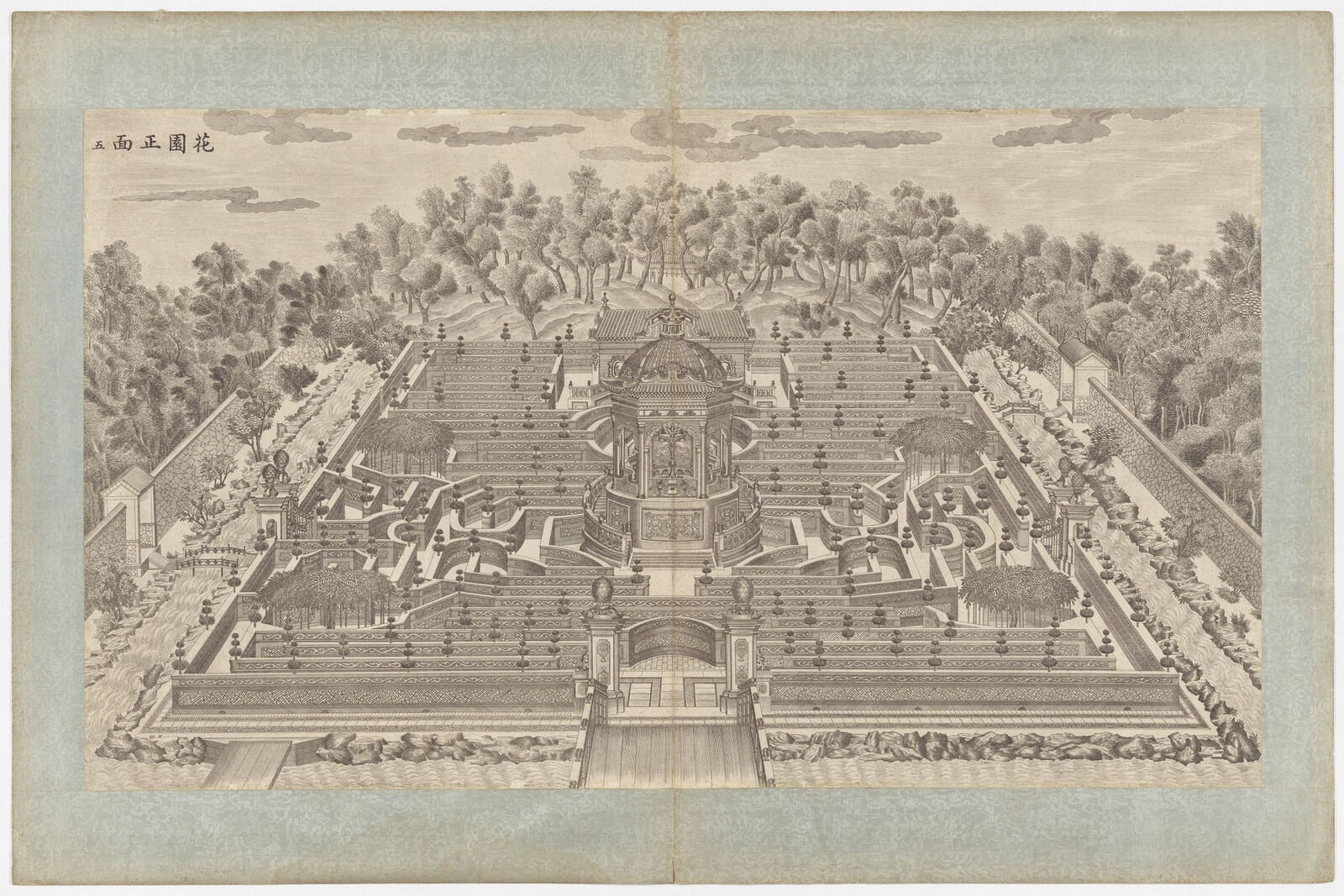

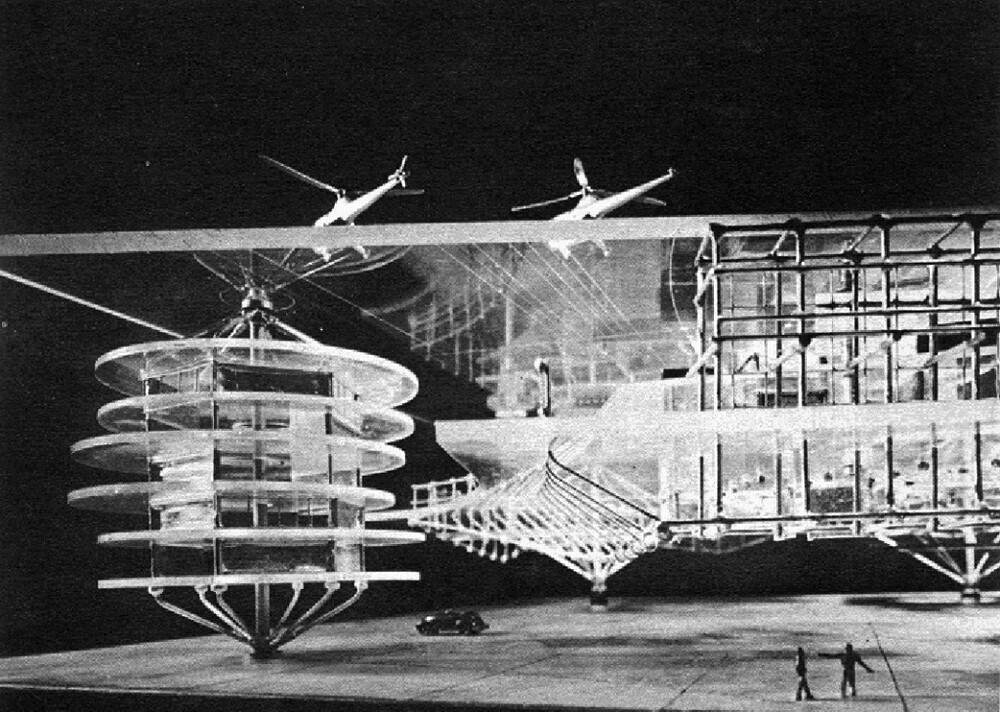

What is life in a world where I am also the architecture of that world? Until recently, the history of Western scientific development has been a history of a brutal spiritualism, where discoveries of cosmic mechanics only further displace the human observer. I might gain access to God’s computer in a quest to commune with higher forces, only to progressively discover that material forces are programmed as an inhospitable abyss in which my life means nothing. Science might come to the rescue to draw these material forces back under human command, weaponizing and industrializing their power to limit their threat. From Descartes conceding that we possess an exceptional soul in spite of being animate machines and Darwin’s allowing us an aristocratic status in spite of being animals, a brutal self-extinction has haunted (perhaps even guided) the European spiritual imaginary since the Enlightenment. We might eventually consider that mechanical forces and animal survival might have better things to do than conspire to exterminate our human kingdom the moment we observe them. In the meantime, we still need to contend with a world or worlds that serve our every need in the absolute, even amplifying them into architecture, sealing us in and serving us at the same time.

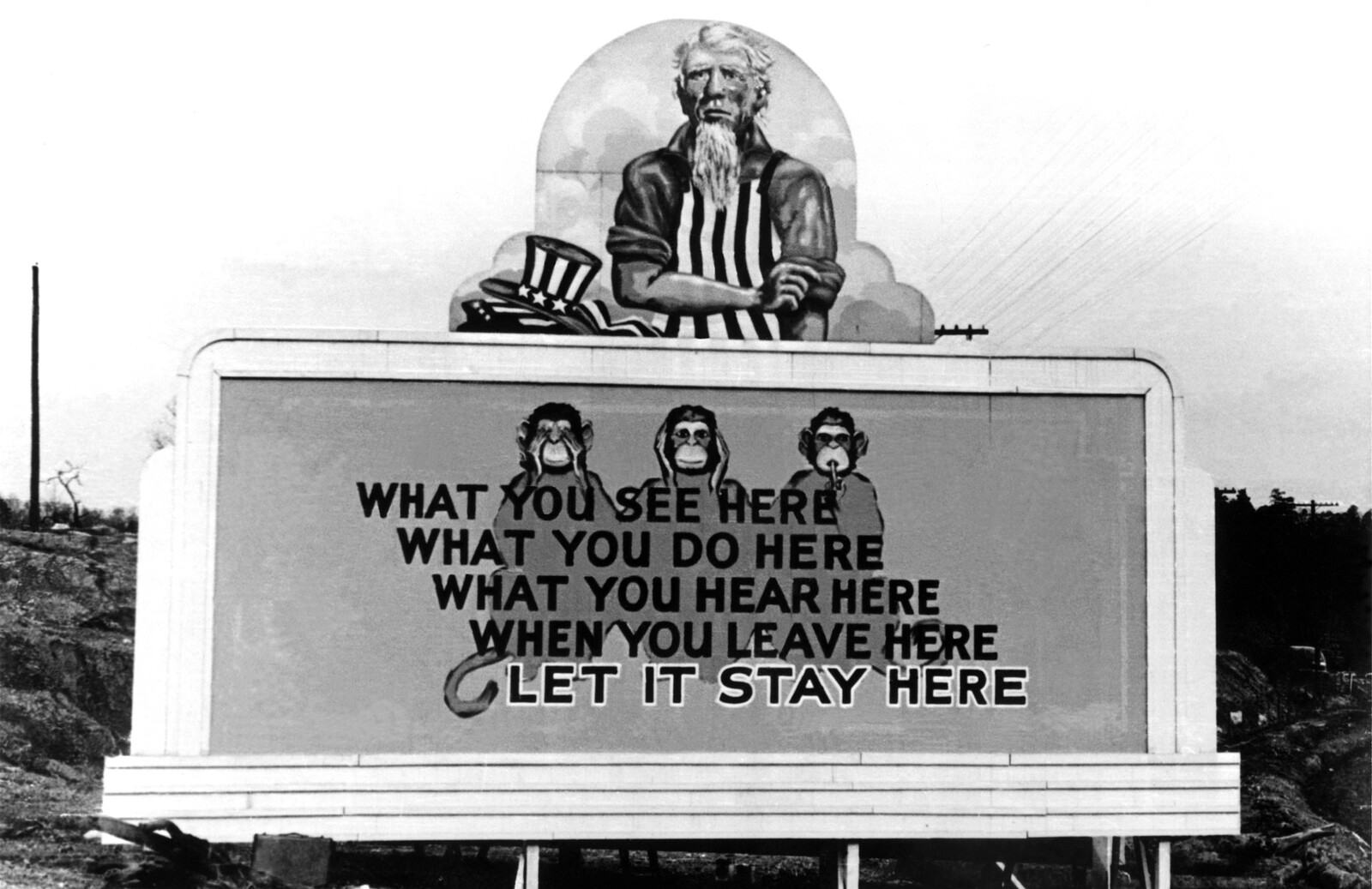

For Jacques Derrida (whose widow, Marguerite Derrida, recently died of coronavirus), the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center marked the manifestation of an autoimmune crisis, dissolving the techno-political power structure stabilized for decades: a Boeing 767 was used as a weapon against the country that invented it, like a mutated cell or virus from within. The term “autoimmune” is only a biological metaphor when used in the political context: globalization is the creation of a world system whose stability depends on techno-scientific and economic hegemony. Consequently, 9/11 came to be seen as a rupture which ended the political configuration willed by the Christian West since the Enlightenment, calling forth an immunological response expressed as a permanent state of exception—wars upon wars. The coronavirus now collapses this metaphor: the biological and the political become one. Attempts to contain the virus don’t only involve disinfectant and medicine, but also military mobilizations and lockdowns of countries, borders, international flights, and trains.

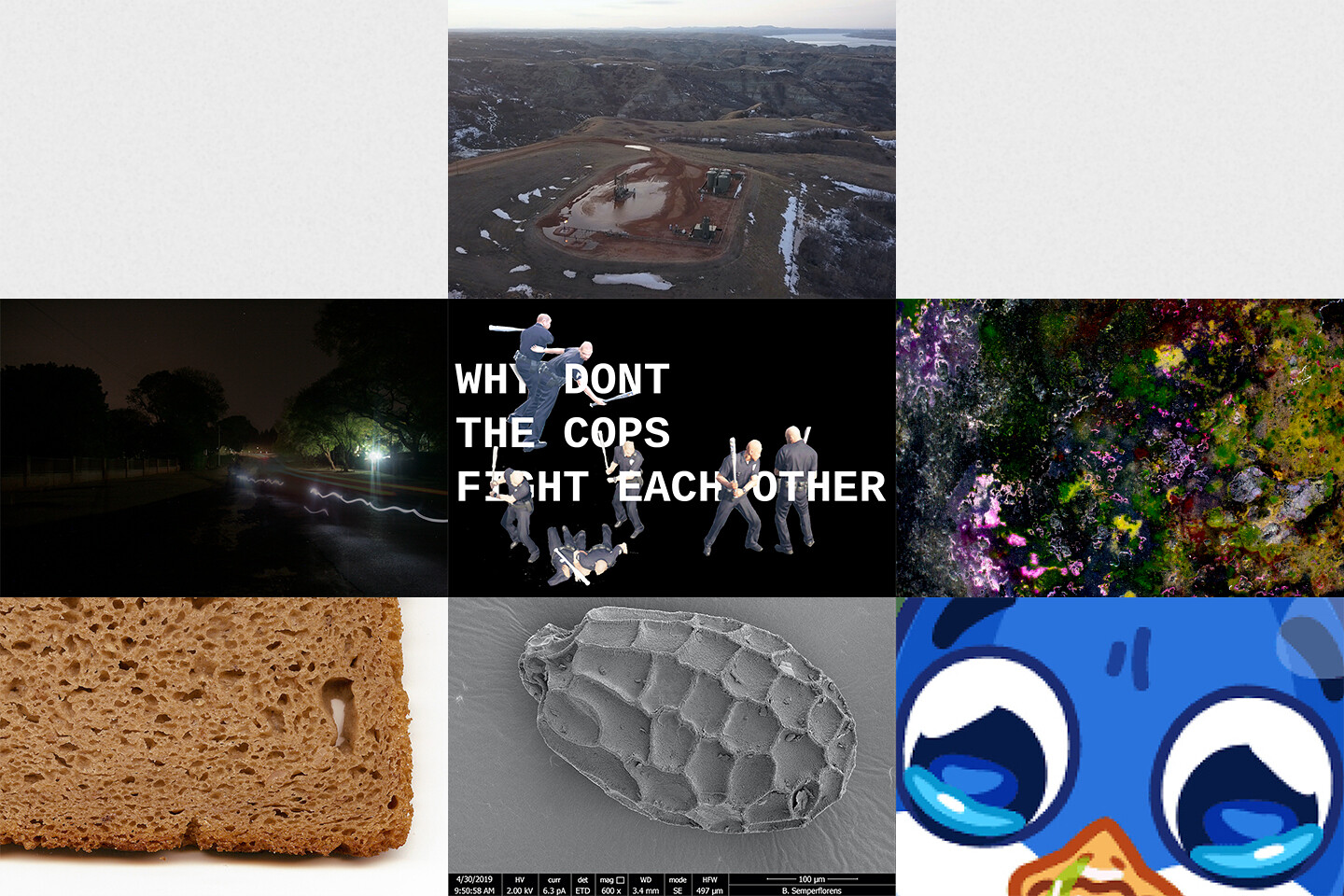

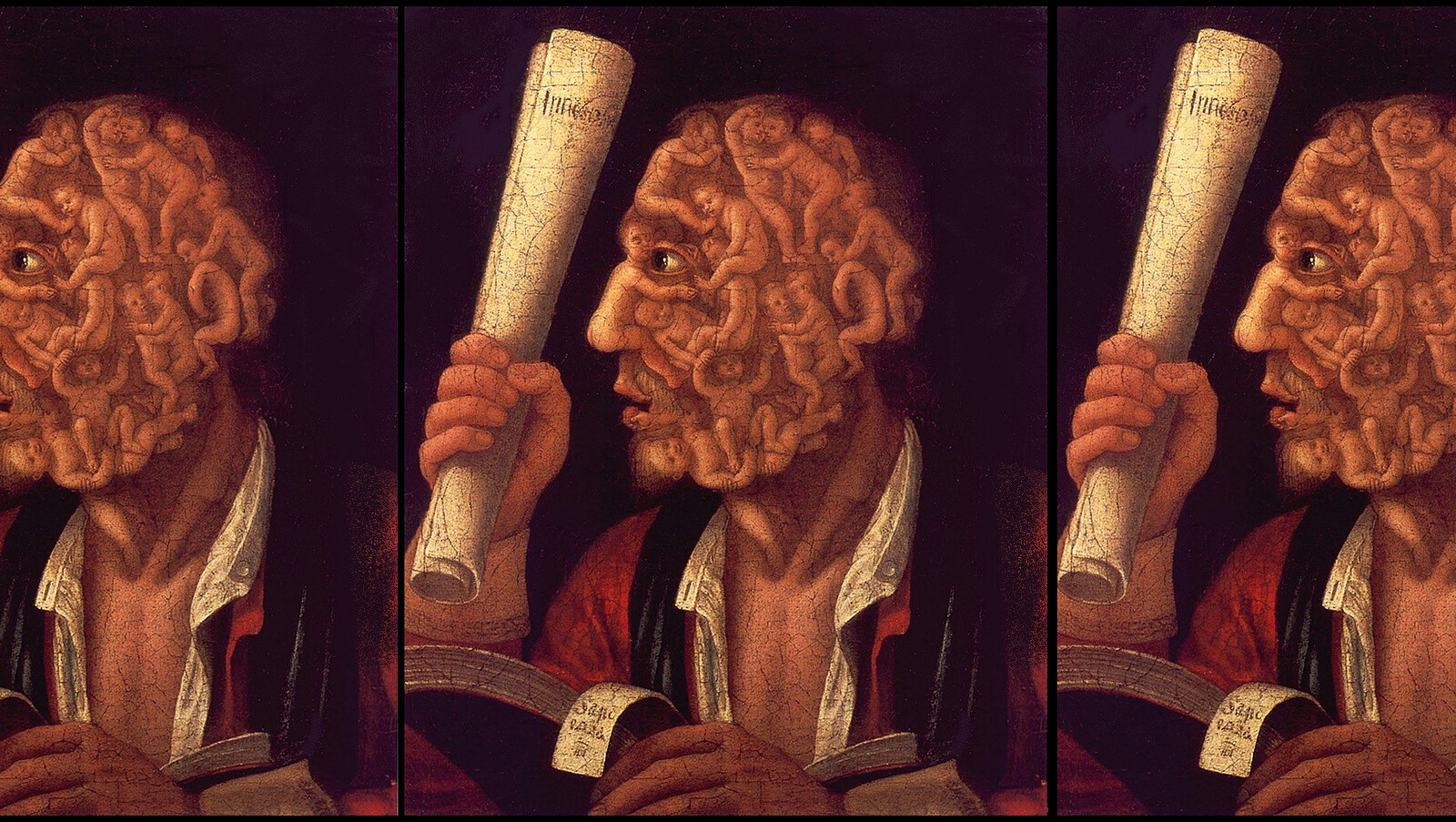

Art after culture. Just to say the simplest and most obvious thing: culture, in the broadest sense of the word, is good at pointing to things and naming them, but not so good at describing relationships between things. It privileges declarations, right answers, universals, and elementary particles. It is captivated by circular logics and modernist scripts that celebrate freedom and transcendent newness—narrative arcs that bend toward a utopian or dystopian ultimate.

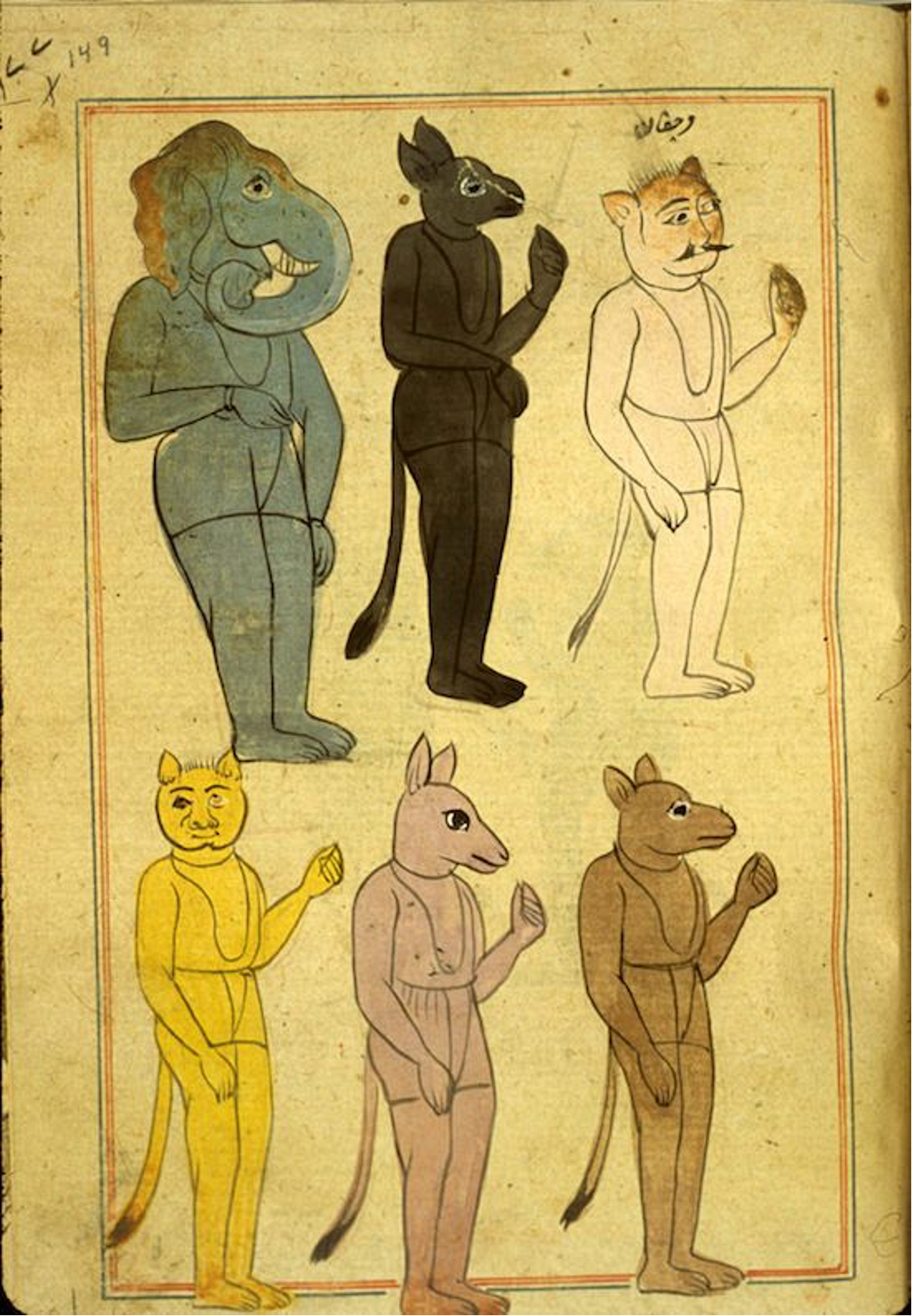

Say the gods latched a chain to the heavens in an effort to yank Zeus down. Well, Zeus would simply pick it up, give it a tug, and the rebel gods, their earthly minions, the entire carnal world, would be flung through the cosmos to an untimely end. With a mere twist of his finger, Zeus could take control of the chain: as a weapon, a keepsake, a necklace for the peak of Olympus. Zeus never acted on this threat, but his gauntlet kept hanging. With each passing era, it grew ever more like a chain. The natural world took a liking to this object. Creatures began to clamber up and take shelter in its links. By all accounts, they loved the altitude and the elliptical life. Gods come and go, and still the chain keeps hanging. Trees have sprung up around it, but if we look closely, we can see it: a weathered thing, more rust than metal; a testament to all we’ve forgotten to remember—to the worlds of old epistemologies, to the aliens of the Enlightenment. At some point, the future may reclaim this chain.

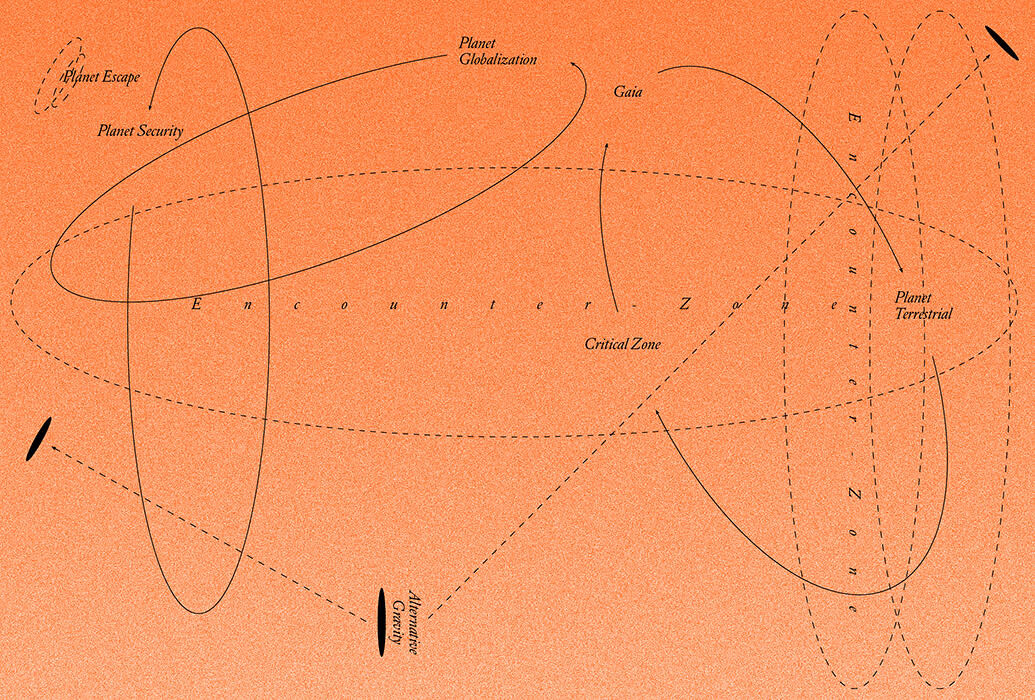

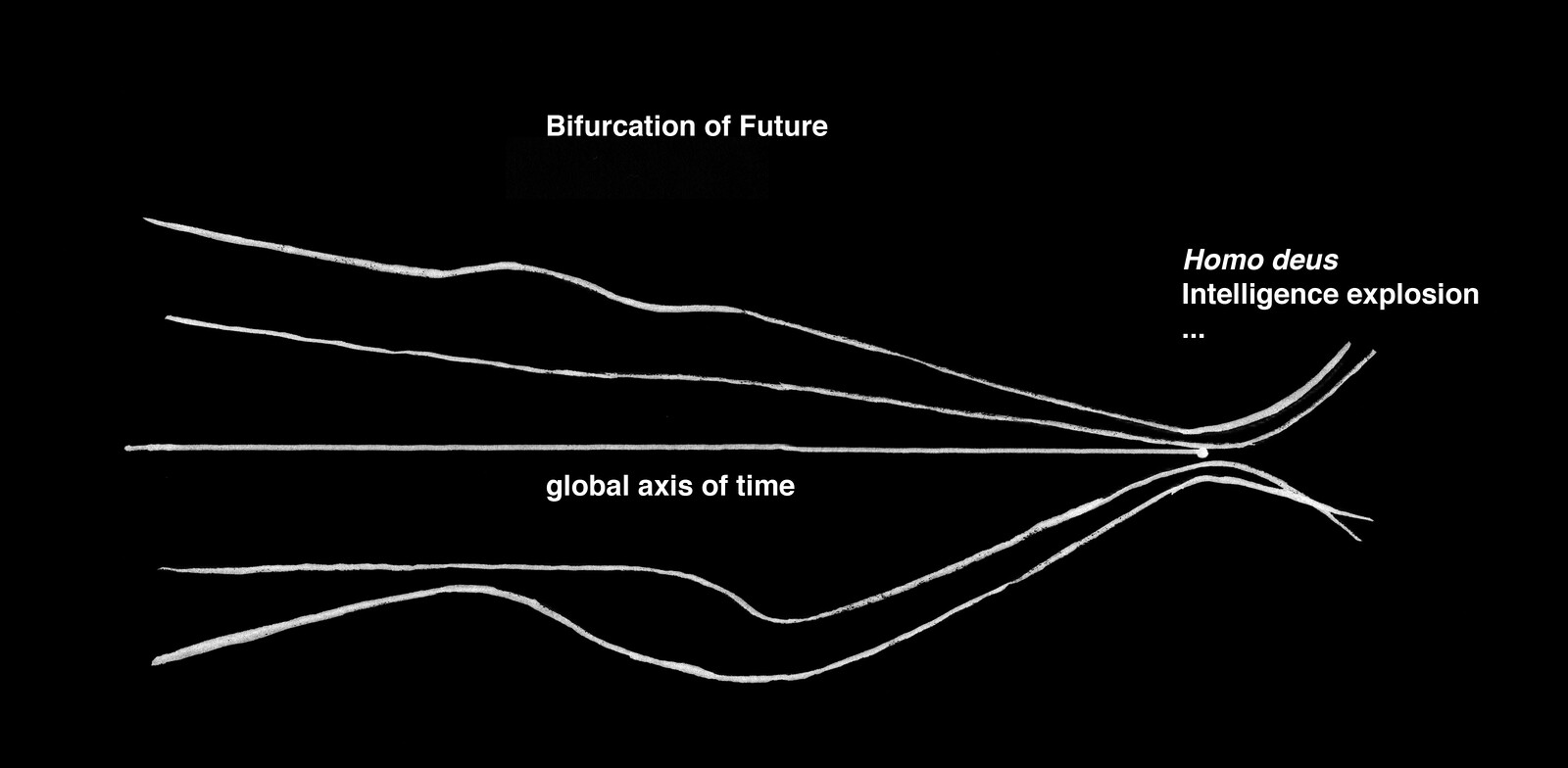

On the other hand, we may understand Kissinger’s end-of-Enlightenment claim as marking the full realization of a single global axis of time in which all historical times converge into the synchronizing metric of European modernity. It is the moment of disorientation—a loss of direction as well as of the Orient in relation to the Occident. The unhappy consciousness of fascism and xenophobia arises from this inability to orient: as a response, it offers an easy identity politics and an aestheticized politics of technology. More broadly, such a disorientation can be seen as a desirable and necessary deterritorialization of contemporary capitalism, which facilitates accumulation beyond temporal and spatial constraints. War is the technique of disruption par excellence, vastly more effective than Uber and Airbnb.

Regardless of which Christian sect we ascribe it to, universalism remains a Western intellectual product. In reality there has been no universalism (at least not yet), only universalization (or synchronization)—a modernization process rendered possible by globalization and colonization. This creates problems for the right as well as the left, making it extremely difficult to reduce politics to the traditional dichotomy. The reflexive modernization described by prominent sociologists in the twentieth century as a shift from the early modernity of the nation-state to a second modernity characterized by reflexivity seems to be questionable from the outset.