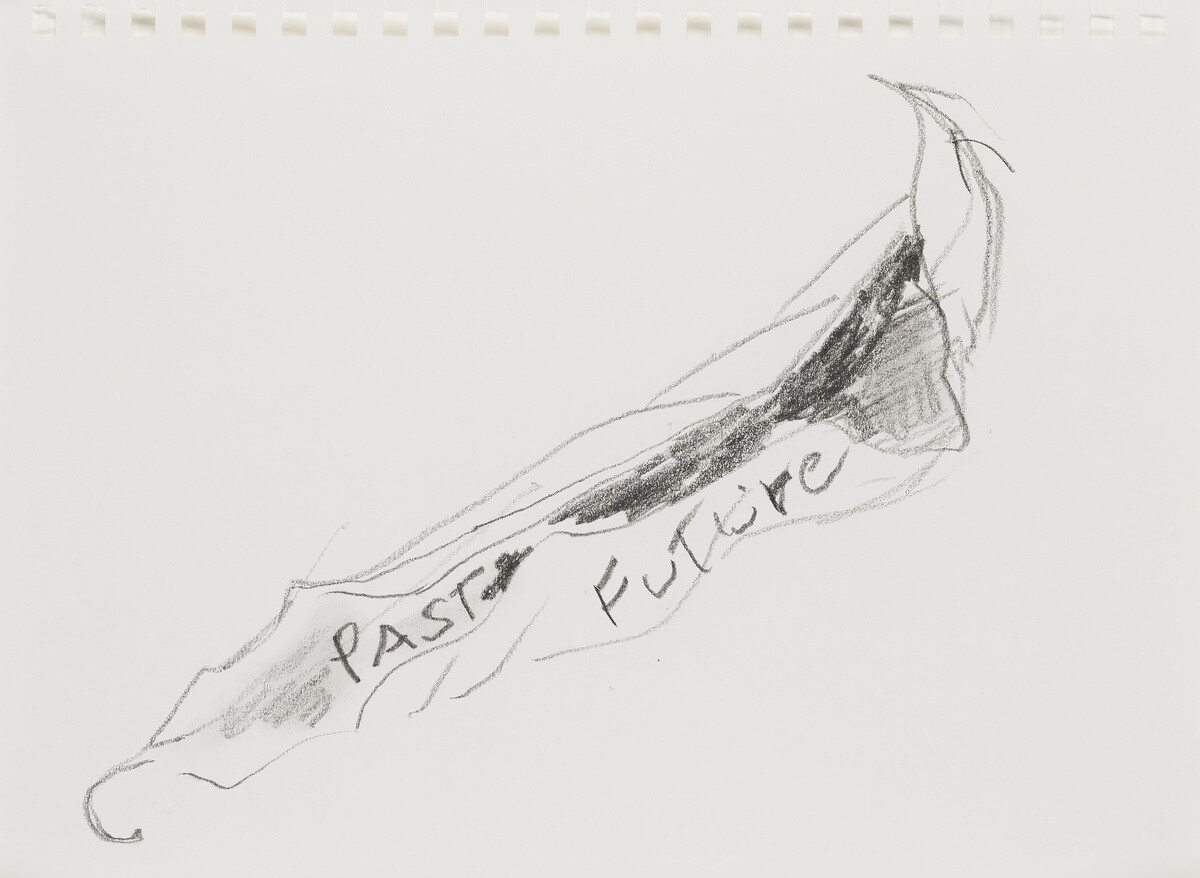

For Choi, time becomes fused and stuck around trauma. To experience profound grief is to be taken out of the flow of time, yet “temporal magic” is what allows for an escape from the inexorable and crushing movement of history: grief as resistance and resistance as grief. There are very good reasons to lose one’s narratives, both as individuals and as nations. One of the goals of experimental writing like Choi’s is to disrupt official narratives, histories, and images along with, more importantly, their meanings—although they’re more like presumptions and predispositions—because narrative is a prime vehicle in which to smoothly embed them.

Launch of e-flux journal #144

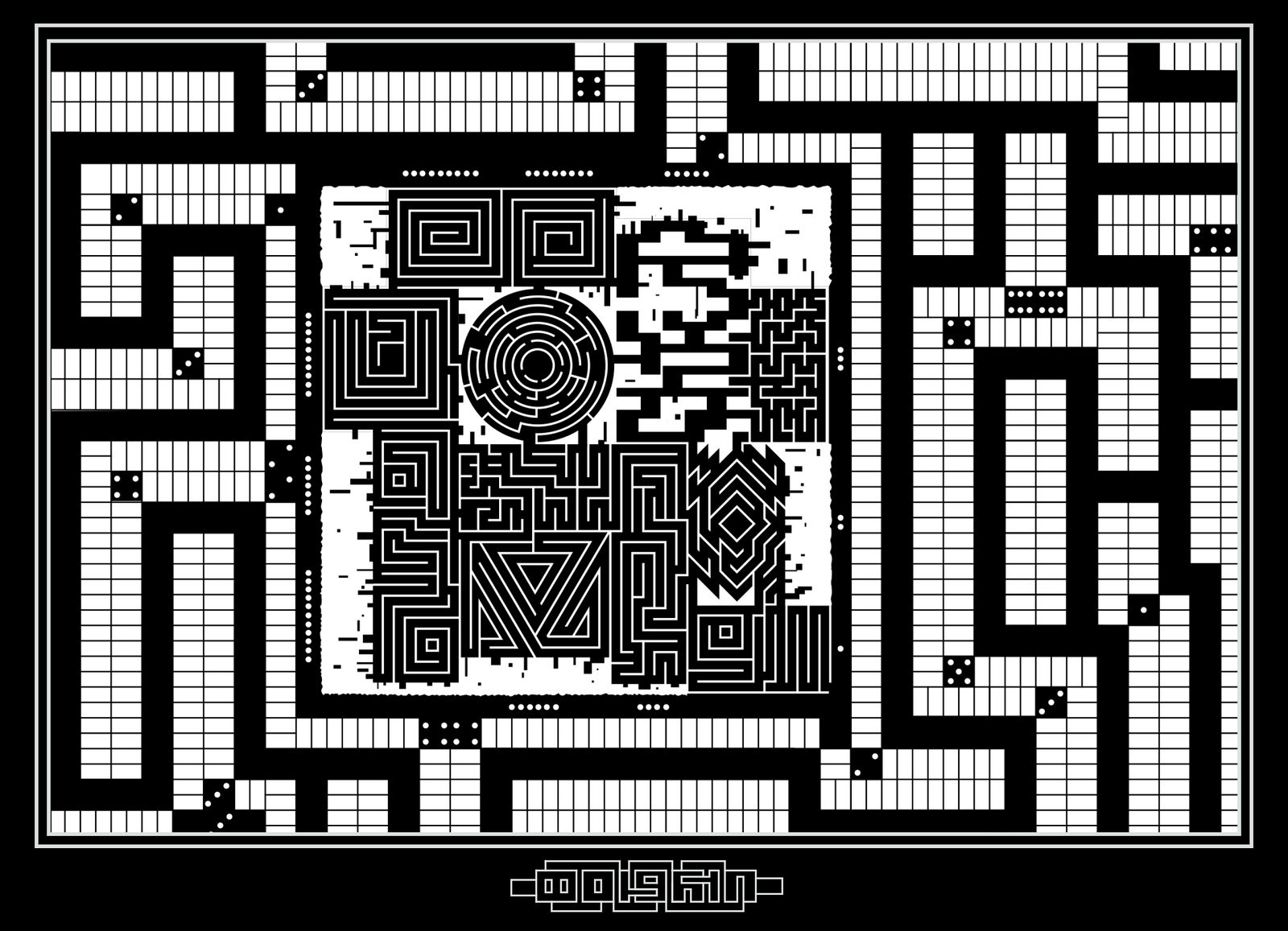

How many artists and art practitioners have you met who began in music? Maybe visual art offered them some relief from the rigors of musical scale and tonal structure, a broader material and conceptual palette. But what of those who stayed with musical form and sonic language while also testing its limits? Music’s own wildness takes endless forms, from the modern supernatural of recordings and long-range transmissions over air or wire to the synthetic identities promised by the energy injections of new popular sounds. The strange magical or divinatory interests of experimenters and composers have their own occult physics, automations, locutions. In this vein, we are very excited to work with curator Daniel Muzyczuk on the first in a series of issues retracing the weird and winding paths connecting musical and artistic experiments.

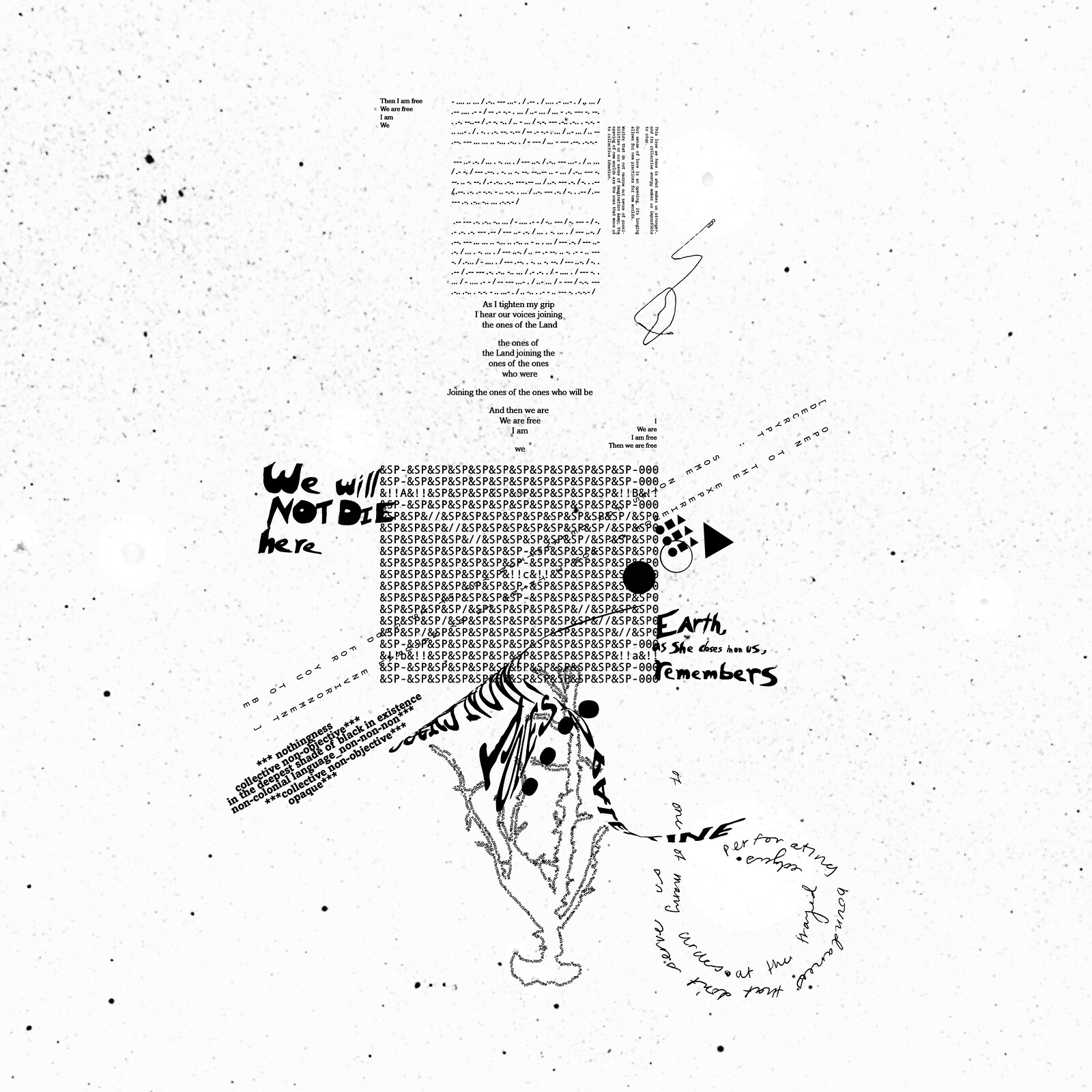

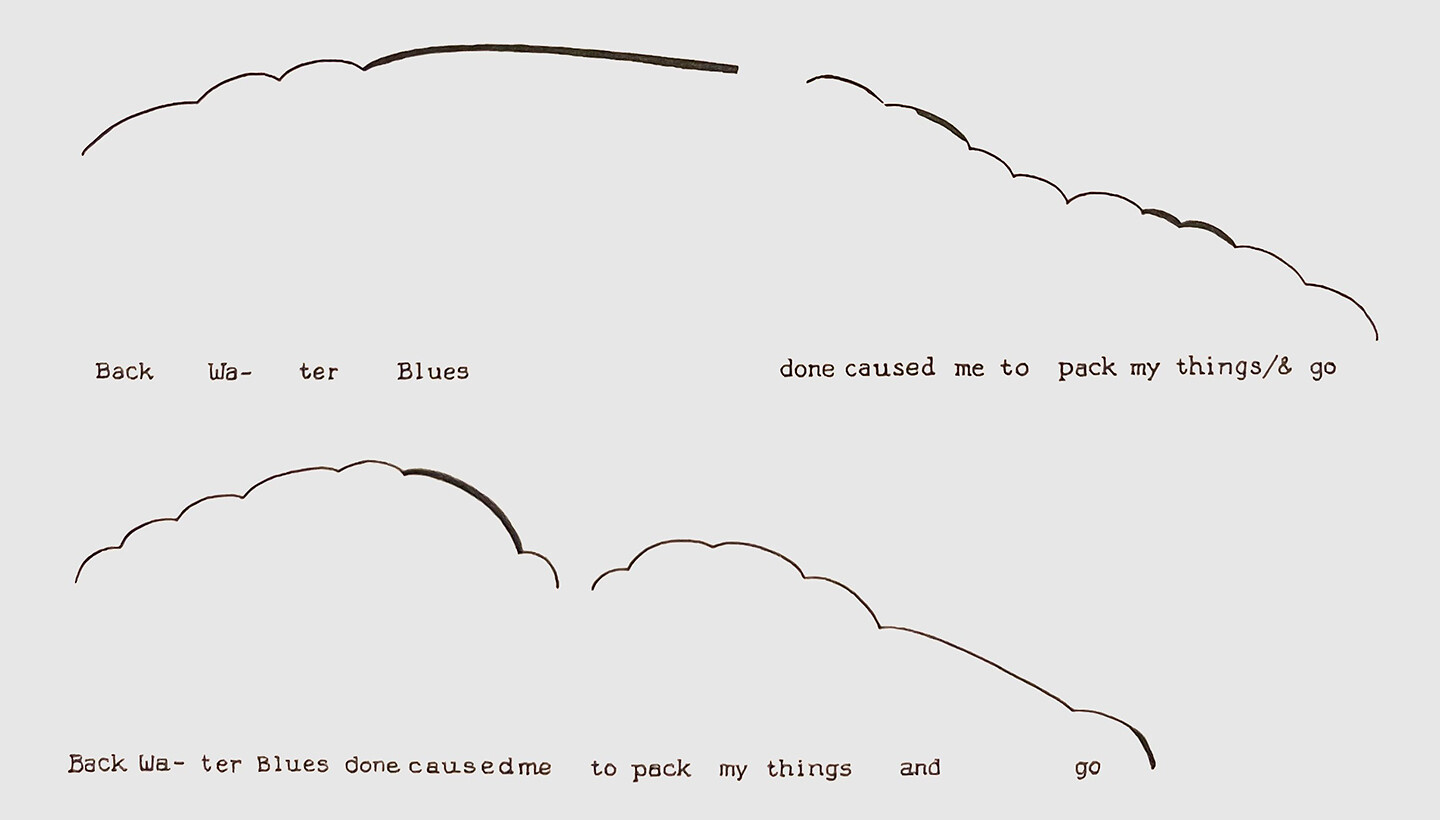

The entire mystery of the universe was contained in the poetics and the fact that you can’t ever find the stress. You can’t locate it exactly because it’s this blank place. I think that when you write a poem, you actually enter a blank space. And when you’re writing, you are actually feeling nothing. What the poetry is about is not taking place. Some blank thing is happening. And then you define it by before and after. There’s some kind of bleeding between before and after your entry into the blank space.

If the ghosts of Liszt and Chopin have become fluent English speakers while in the land of the dead, isn’t it strange that they have accents? In fact, an accent is just like a composer’s signature style: a small detail that reveals the origin of a given piece. Style was what experts looked for when examining the scores written down by medium Rosemary Brown for confirmation of life after death. But why should a dead composer have the same style as when they were alive?

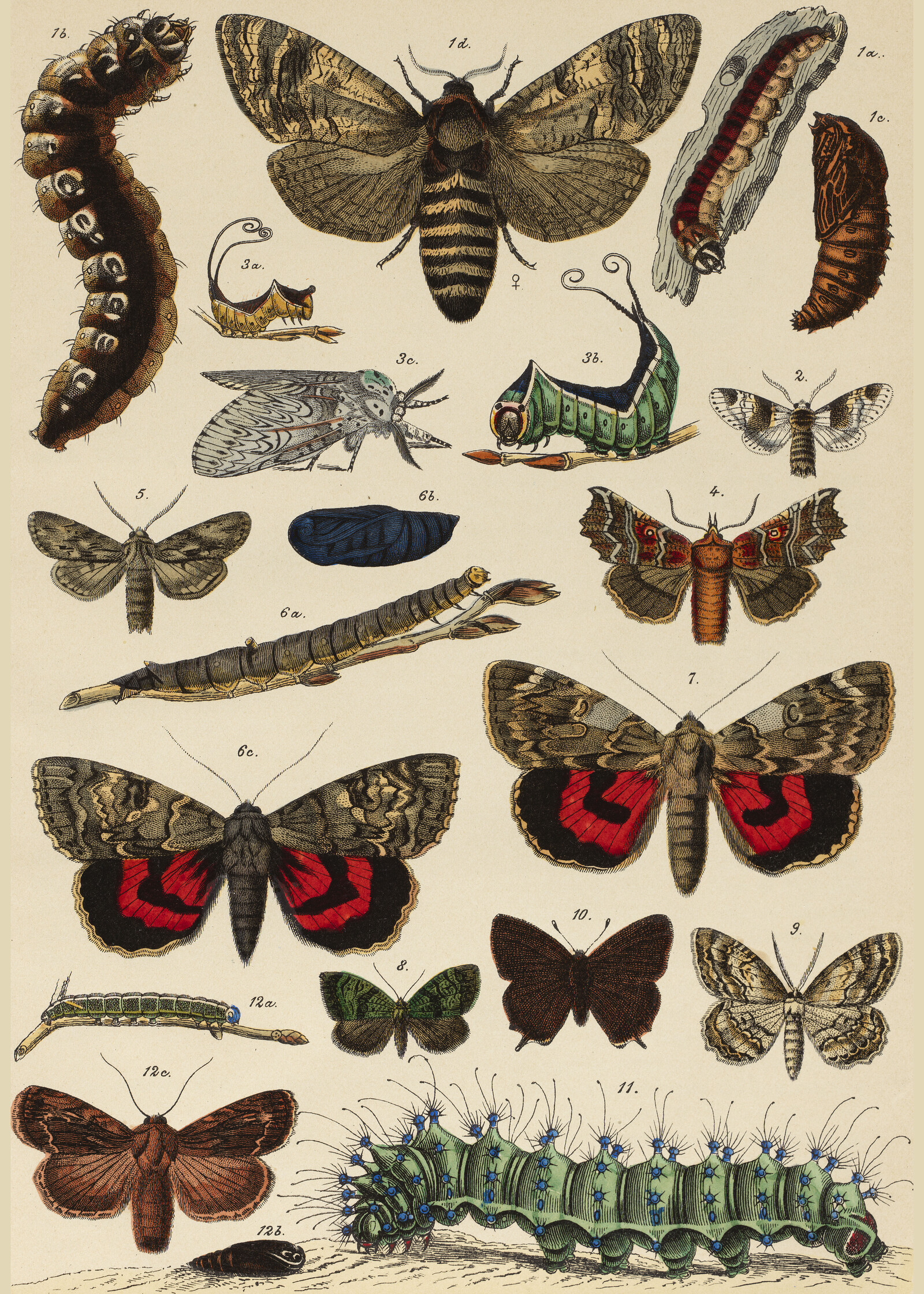

Music is a kind of sound, and poetry is a kind of language. Sounds are arranged into music, as language is arranged into poetry. But what’s considered “musical” or “poetic” moves us beyond formal arrangement, beyond even their respective media, into the realms of discourse. The sense of what’s “musical” and what’s “poetic” can differ and can definitely vary, but generally one looks to be moved, or even transported, into realms of feeling, spirit, and memory. This is the lyrical mode: the ancient lyre shaped words—lyrics—into rhythmic and tonal patterns to give us poem forms—elegies, odes, sonnets—carrying song through language’s musically inflected prosodies.