e-flux Criticism presents: On editing and the creative process

The traces of this generation remain disturbing to any dominant order, sometimes even to their former peers and friends. Their true agendas, aspirations, and dreams, however silenced or put on hold, continue resurfacing amidst historical readjustments. Their most intimate convictions were never fully bent, not even by the most sadistic of repressions inflicted on them. A unique invisible thread links the disparate trajectories of intervention of these last protagonists on the shared stage of the short century.

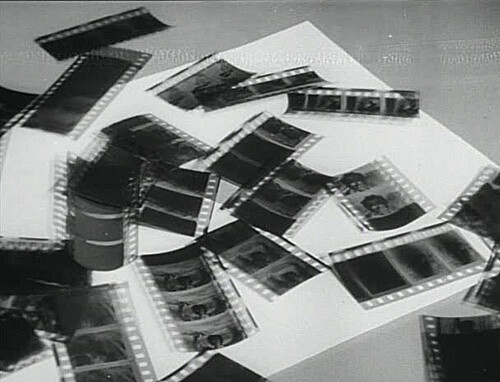

What could a practice of politicizing the image in the twenty-first century look like, considering that navigation—the computational condition of contemporary image-processing—updates, calculates, and incorporates the frame excessively and continuously into the image-making process? In order to render more palpable the beginning of a political ontology of image navigation by means of computation, we should remind ourselves of the principle of twentieth-century montage, which can offer a potent point of departure. Much has been written and produced in the name of montage. In 1967–68, film students, including Harun Farocki, announced the Dsiga Wertow Akademie, an occupation of their film school, the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin, an act that paid tribute to montage as a cine-political practice. Montage was pioneered by Esfir (Esther) Schub and Dziga Vertov, emerging from the world of Soviet cinema during the period of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1918. In other words, montage’s potency to mobilize the image for emancipatory processes was initially built from participation in communist world revolution.

Parmigianino’s painting suggests that finding orientation should be conceived as a fundamentally tactile, sensuous, nonvisual matter (and, considering the pedophilic gaze impelled by the picture, a rather disconcerting one too). The boy’s hand, more than his vision, is the navigational device par excellence. It also serves as a precedent for another infamous hand of a boy with “a passion for maps” some four centuries later. Charlie Marlow, the narrator of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 Heart of Darkness, recalls his childhood dreams of “blank spaces on the earth.” “And when I saw one that was particularly inviting on a map,” Marlow muses, “I would put my finger on it and say, ‘When I grow up I will go there.’” Both hands, first in the sixteenth-century painting and then in the turn-of-the-twentieth-century novel, point to an evolving set of protocolonial, colonial, and neocolonial gestures that continue to inform geopolitical visual cultures. The hand is used as a scaling device, allowing one to literally touch the cartographic representations of often vast geographical areas, thereby making available an individual bodily experience of exploration, travel, and possession. In the mind deformed by colonialism, the touching of the map anticipates the grabbing of the land.