It may be that the process we call evolution, which led to more complex life-forms on earth, was not meant to improve chances for survival, but to acquire a higher-definition picture of the world, moving from lower-resolution (two pixels) toward much higher-resolution images. Thus, improving chances of survival was only a secondary goal—a necessary means for life’s need to see itself and the world around it in the best, clearest, sharpest possible way.

To see technology only as a form of anthropogenic violence would again ignore the generative synthesis of mechanistic analysis and materialist supposition. The denial of progress, even if limited to the technological output of human beings, requires treating technological objects both mechanically and materially, as well as demonstrating particular forces and matters. Or as philosopher Gilbert Simondon approached it, technology can be defined as a designed tool on the one hand and as having a life of its own on the other.

In the West, exploration of the deep sea has historically conjured images of ancient monstrous mythological creatures such as the Leviathan, the Kraken, and more recently the Cthulhu, among other figures of alterity and the unknown. Characterized by scientists and mainstream media alike for being “utterly alien,” newly discovered undersea life-forms are no longer gigantic, but microbial. Descriptions often mix in themes of outer space exploration in the evocation of the “alien” and the technical challenges of building robotics to withstand extreme underwater pressure conditions. Perhaps the recent reconception of evolutionary trees prompted by underwater hydrothermal vents, over a century after the initial Western exploration of the Galápagos, contributes to a particular form of modern mythology—a science-led search for a last common ancestor of sorts fueled by biogenetic labs.

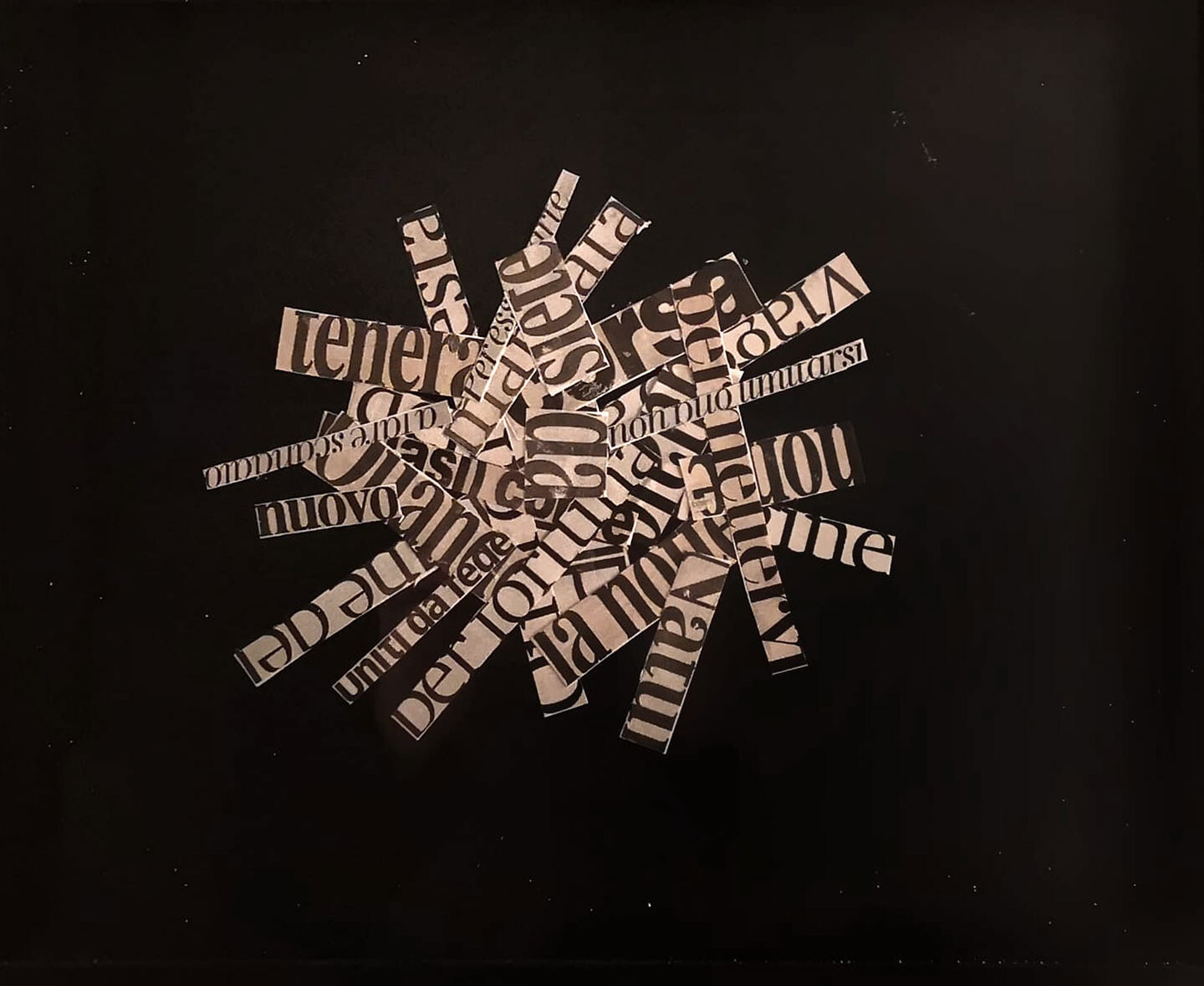

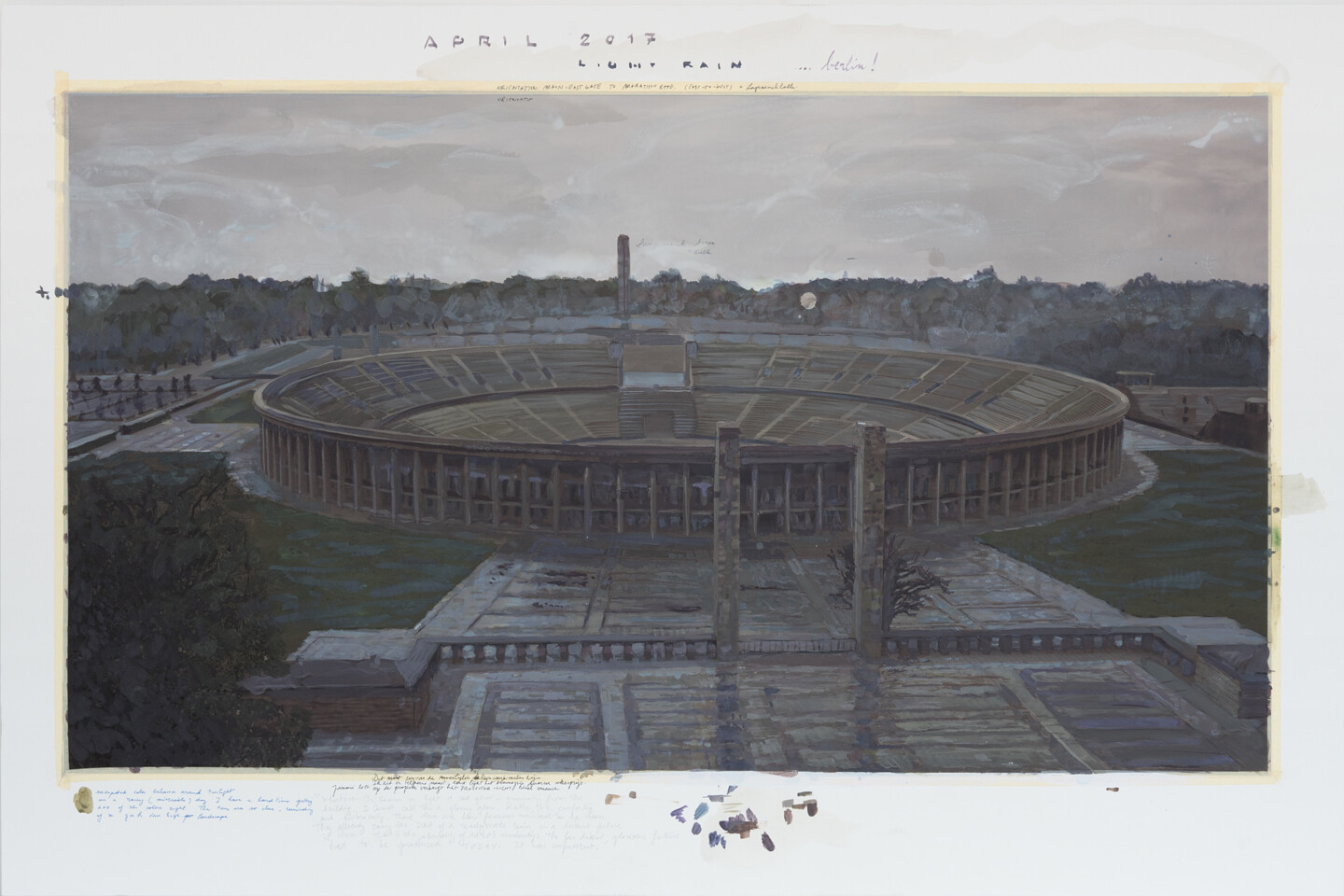

Forty years ago, I remember shouting, “No future! No future!” with some young British musicians. I thought it was the provocation of an unlikely avant-garde. Now, everybody thinks that the future is over; now, the sentiment aligns with a conformist position held by most of humankind. “No future” has become common sense, and this is why cynicism is expanding in contemporary culture, in contemporary political behavior. Futurism was the expression of a society that expected something from the future, and of a society that truly felt the warmth of community, whether encapsulated in the nation, the family, or social ties to working communities. All the above was the reality of lived experience a hundred years ago. No more! Today, the nation is a nonexistent thing. The dissolution of the nation is an effect of the pervasive digitalization of information and of power based on information. Do you think that Google belongs to the United States? Not at all. The United States belongs to the territory of Google. So does Italy, and France, and so on.

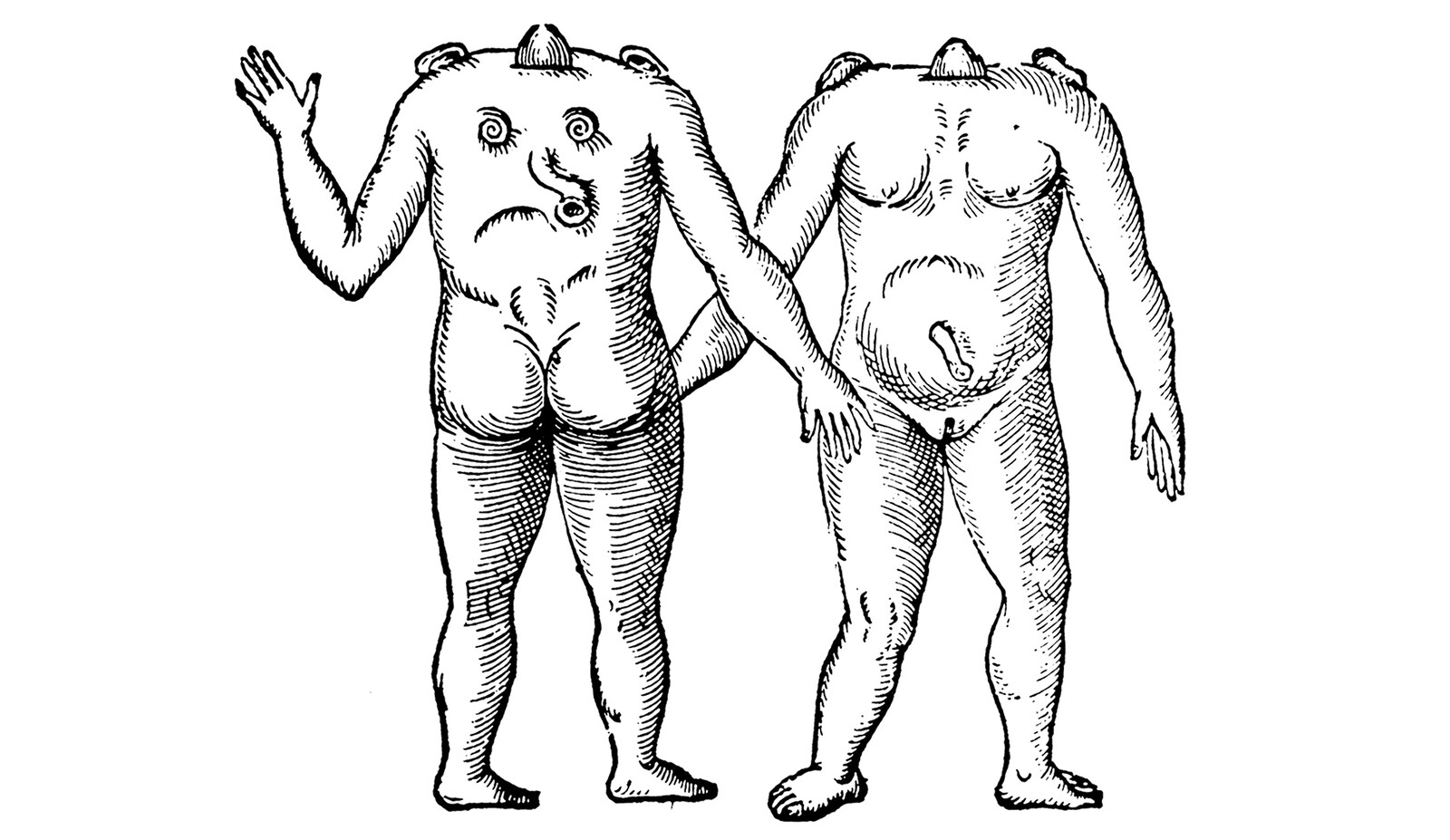

Our most ancient animal ancestor, Dickinsonia costata, is categorically lodged between pestilence and creature. Or rather, Dickinsonia dithers in a space betwixt bacteria and animalia. Let us accept that our beginnings find us plunked down in the center of the margin. She, a flat mat, possesses an expanding physical symmetry. Some bugs are fugitive like this; see how they slide under your domestic things. Yet her remains are found as fossils on remote Russian cliffs. Her gravesite overlooks a marginal sea, a part of the warming Arctic Ocean—a site of intense oil and gas speculation. The slightest psychedelic tendency urges me to bypass my oral and historic memory and uncover an otherworldly and cellular memory of Dickinsonia costata: “Mama!?” I lisp.

YH: We live in an age of neo-mechanism, in which technical objects are becoming organic. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, Kant wanted to give a new life to philosophy in the wake of mechanism, so he set up a new condition of philosophizing, namely the organic. Being mechanistic doesn’t necessarily mean being related to machines; rather, it refers to machines that are built on linear causality, for example clocks, or thermodynamic machines like the steam engine. Our computers, smartphones, and domestic robots are no longer mechanical but are rather becoming organic. I propose this as a new condition of philosophizing. Philosophy has to painfully break away from the self-contentment of organicity, and open up new realms of thinking.

Say the gods latched a chain to the heavens in an effort to yank Zeus down. Well, Zeus would simply pick it up, give it a tug, and the rebel gods, their earthly minions, the entire carnal world, would be flung through the cosmos to an untimely end. With a mere twist of his finger, Zeus could take control of the chain: as a weapon, a keepsake, a necklace for the peak of Olympus. Zeus never acted on this threat, but his gauntlet kept hanging. With each passing era, it grew ever more like a chain. The natural world took a liking to this object. Creatures began to clamber up and take shelter in its links. By all accounts, they loved the altitude and the elliptical life. Gods come and go, and still the chain keeps hanging. Trees have sprung up around it, but if we look closely, we can see it: a weathered thing, more rust than metal; a testament to all we’ve forgotten to remember—to the worlds of old epistemologies, to the aliens of the Enlightenment. At some point, the future may reclaim this chain.

e-flux lectures: Franco “Bifo” Berardi, “IS THERE A WAY OUT?”