Soil, Struggle and Justice: Agroecology in the Brazilian Landless Movement

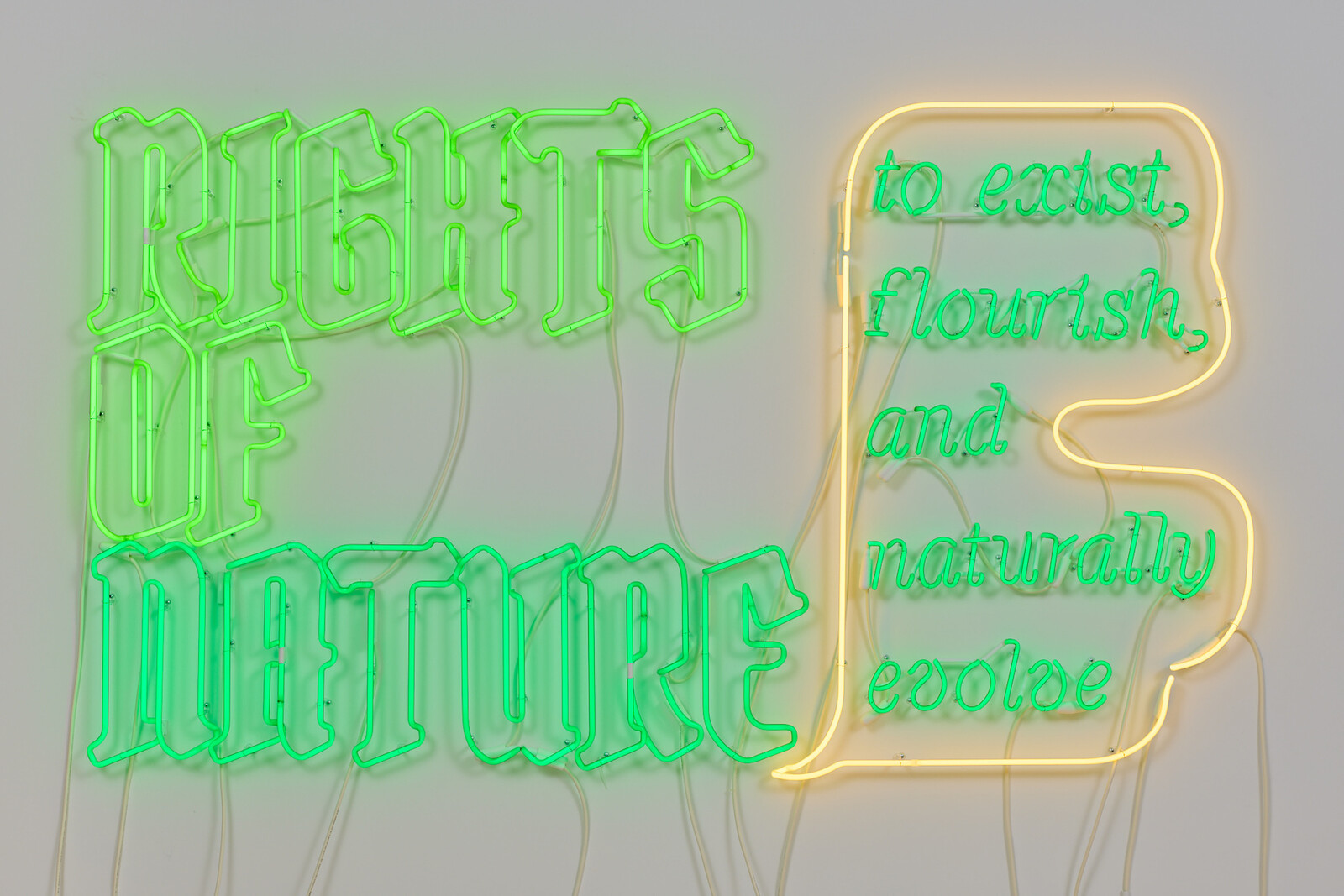

The mediated, sentient, and intelligent plant potentially invites us to think about nature, plants, technology, and ourselves-as-humans in different ways. As plants in particular are revealed as agentic, intentional beings, the mediated plant potentially invites us to develop more caring, attentive, and communicative attitudes toward the vegetal. In this way, the mediated plant can push us forward in the urgent “struggle to think differently” that Val Plumwood called us to join. Perhaps the mediated, sentient, intelligent plant can help us to queer nature, to queer botanics, to queer ourselves-as-humans as we “go onwards in a different mode of humanity.” But why to queer? Why not “simply” to “decolonize”?

Gender essentialism—“women’s empowerment”—overtakes any class or race discourses, which are at the core of internationalist feminist politics. “Global womanhood” becomes a category or a class in itself. Hunger is separated from class and from the failure of states to provide and distribute wealth equally. The main political aim becomes fighting hunger, without any reflection on what has caused this hunger—for example, the failure to subsidize farmers’ material needs; the historical mismanagement of water distribution, which has led to drought in many areas; the overexploitation of underground water (like in the Bekaa valley); the distribution or subsidization of fertilizers for farmers, which over many years has damaged the soil; toxic waste polluting the water; and more generally the laws around property or land ownership, which favor the few at the expense of the many. NGOs do not address this mismanagement at the state level; instead, they try to compensate for it.

Alice Labor