Reclamation

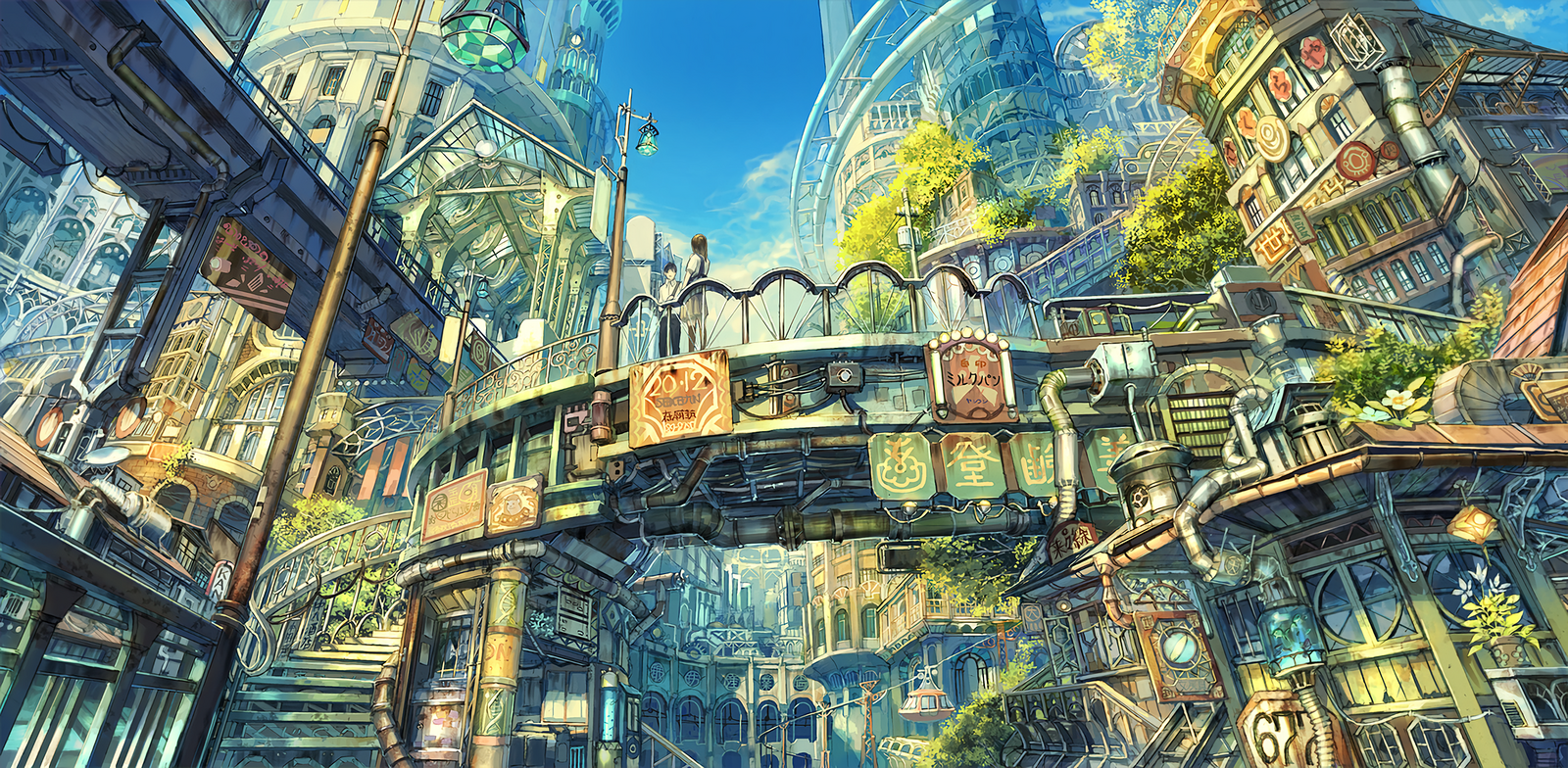

Inaate/se may not be the most obvious example of the science-fictional aesthetics of “Indigenous Futurism,” a term coined by Anashinaabe scholar Grace L. Dillon to describe Native artists who work with science fiction to both refuse the representational expectations of “the Great Aboriginal Story” and play with boundary crossings, claiming the spaces of science, technology, and futurity as their own. Nonetheless, the film employs certain key strategies Dillon finds in such authors, from what she terms “Contact” and “Native Apocalypse” to “Biskaabiiyiang,” an Anishinaabe word “connoting the process of ‘returning to ourselves.’” In so doing, Inaate/se promises an ethics founded on an inhabited futurity, which, no matter how many blows it has suffered, still manages to survive. The Khalils do not attempt to surpass the trauma of erasure; they inhabit and politicize it for a new world to come. In this way, they make the dystopia lived through seven generations a starting point for livelihood.

I’ll put it differently this time: the sovereignty of survivors.

If Dhalgren shows us the crumbling of consumption in a capitalist society, Stalker portrays the collapse of the whole mechanism of production in a state-socialist one—symmetrical disintegrations that reflect the respective priorities of the rival Cold War systems. The collapse in Stalker goes beyond industrial production, which was the raison d’être for the Soviet planned economy as a whole—represented in the film by rusting equipment, warehouses that now store nothing but wind-sculpted sand—extending to the production of knowledge and meaning, the exhaustion of which is portrayed by the Writer and the Scientist. When all the machinery of the state-socialist system begins to seize up, what rationale or guiding principle can sustain people from one day to the next, let alone in decades to come? This is a moral crisis, to be sure—but a systemic, rather than an individual or personal one.