Sylvia Lavin, “Generator’s Vital Infrastructure”

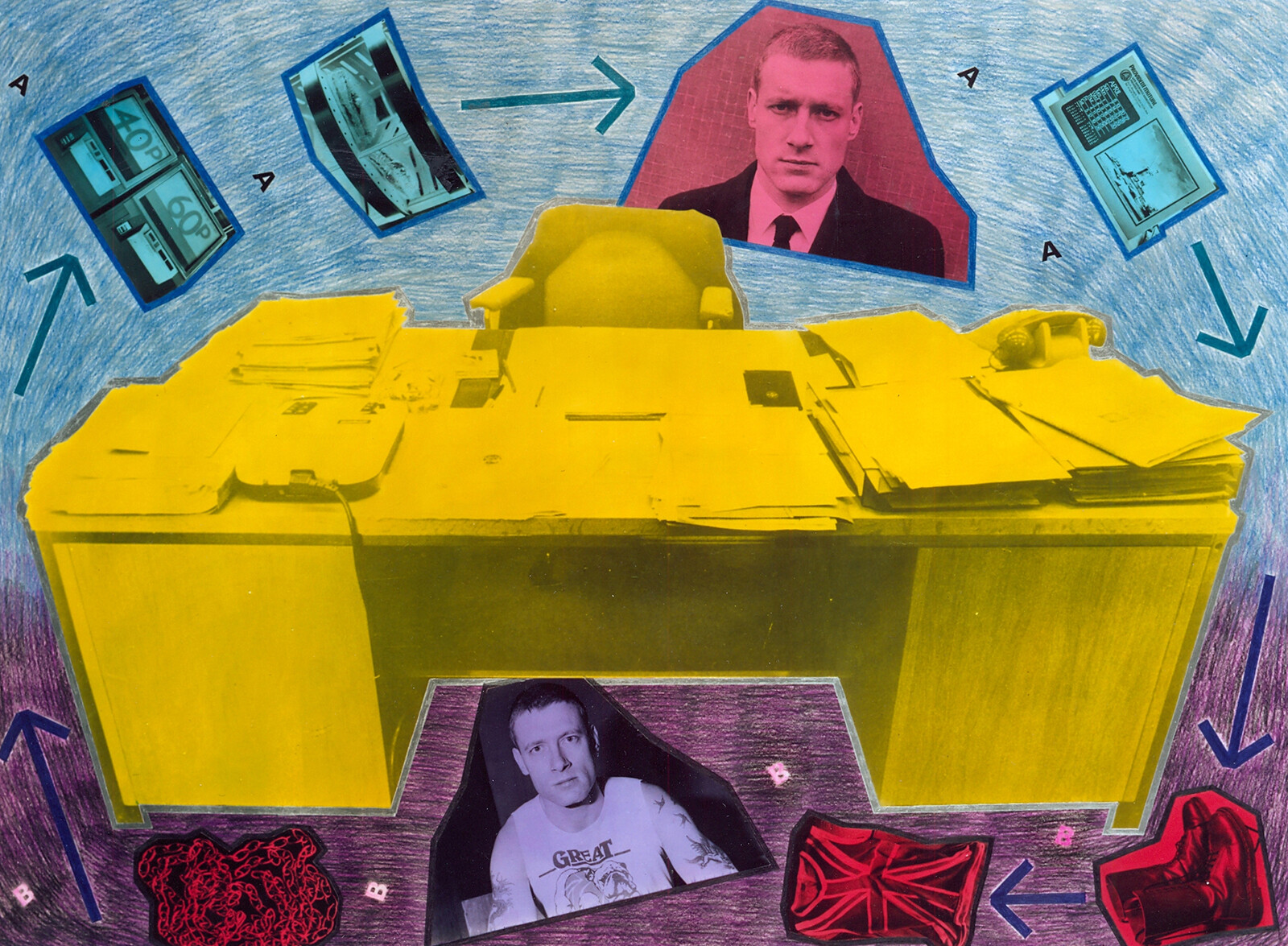

The collapse of reality is not an unintended consequence of advancements in, for instance, artificial intelligence: it was the long-term objective of many technologists, who sought to create machines capable of transforming human consciousness (like drugs do). Communication has become a site for the extraction of surplus value, and images operate as both commodities and dispositives for this extraction. Moreover, data mediates our cognition, that is to say, the way in which we exist and perceive the world and others. The image—and the unlimited communication promised by constant imagery—have ceased to have emancipatory potential. Images place a veil over a world in which the isolated living dead, thirsty for stimulation and dopamine, give and collect likes on social media. Platform users exist according to the Silicon Valley utopian ideal of life’s complete virtualization.

How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File

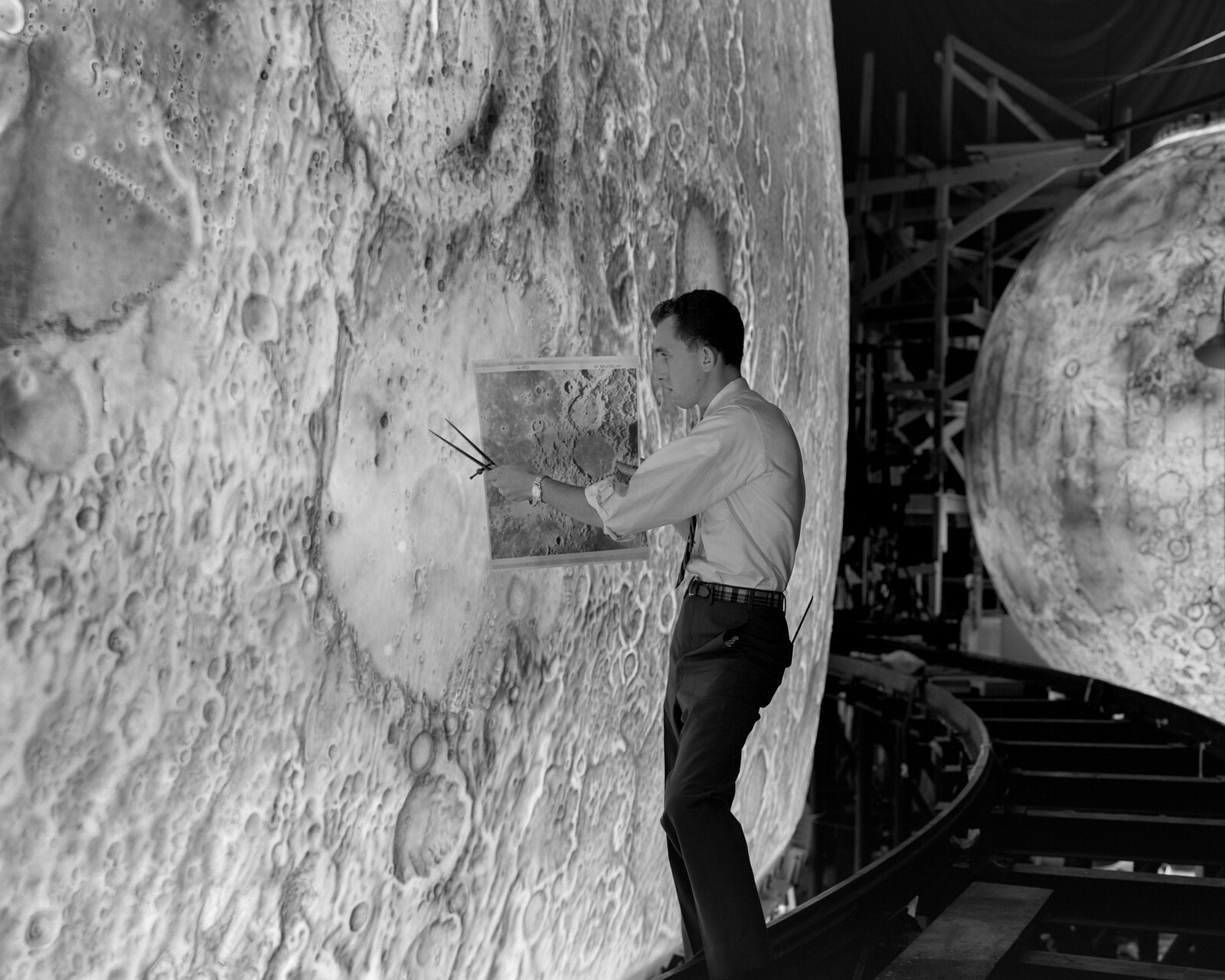

What is life in a world where I am also the architecture of that world? Until recently, the history of Western scientific development has been a history of a brutal spiritualism, where discoveries of cosmic mechanics only further displace the human observer. I might gain access to God’s computer in a quest to commune with higher forces, only to progressively discover that material forces are programmed as an inhospitable abyss in which my life means nothing. Science might come to the rescue to draw these material forces back under human command, weaponizing and industrializing their power to limit their threat. From Descartes conceding that we possess an exceptional soul in spite of being animate machines and Darwin’s allowing us an aristocratic status in spite of being animals, a brutal self-extinction has haunted (perhaps even guided) the European spiritual imaginary since the Enlightenment. We might eventually consider that mechanical forces and animal survival might have better things to do than conspire to exterminate our human kingdom the moment we observe them. In the meantime, we still need to contend with a world or worlds that serve our every need in the absolute, even amplifying them into architecture, sealing us in and serving us at the same time.

In light of current discourses on AI and robotics, what do the various experiences of art contribute to the rethinking of technology today?

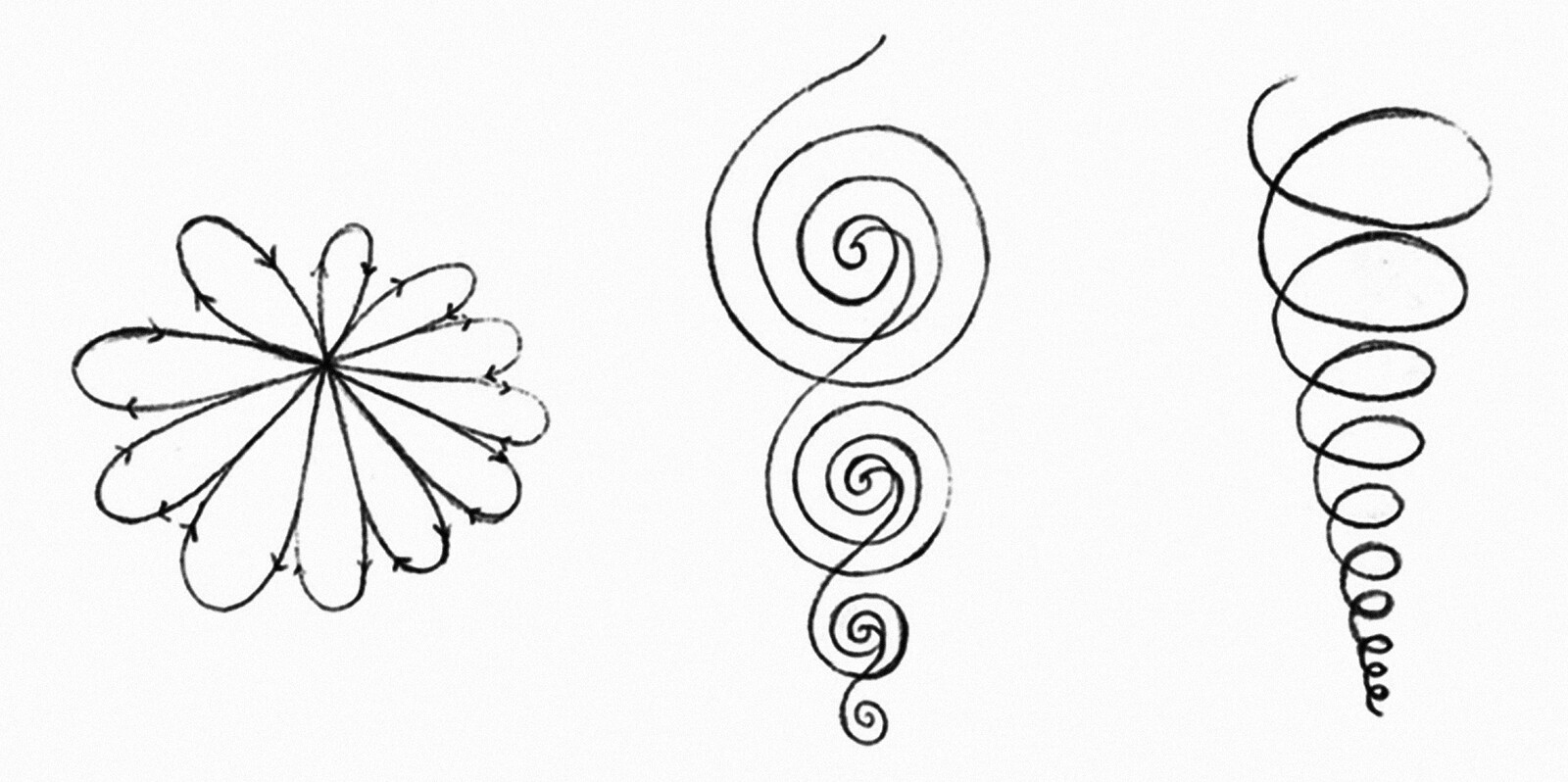

YH: We live in an age of neo-mechanism, in which technical objects are becoming organic. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, Kant wanted to give a new life to philosophy in the wake of mechanism, so he set up a new condition of philosophizing, namely the organic. Being mechanistic doesn’t necessarily mean being related to machines; rather, it refers to machines that are built on linear causality, for example clocks, or thermodynamic machines like the steam engine. Our computers, smartphones, and domestic robots are no longer mechanical but are rather becoming organic. I propose this as a new condition of philosophizing. Philosophy has to painfully break away from the self-contentment of organicity, and open up new realms of thinking.